-

Europa

P2B Regulation – How to adapt Platform services and Search Engines

2 August 2020

- Alternative Streitbeilegung

- Vertrieb

- e-Commerce

Under Vietnam’s presidency of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), after eight years of negotiations, the ten ASEAN member states (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) on 15 November 2020 signed a groundbreaking free trade agreement (FTA) with China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, called Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

The ASEAN economic community is a free trade area kickstarted in 2015 among the above-mentioned ten members of the homonymous association, comprising an aggregate GDP of US$2.6 trillion and over 622 million people. ASEAN is China’s main trading partner, with the European Union now slipping into second place.

Unlike the EuroZone and the European Union, ASEAN does not have a single currency, nor common institutions, like the EU Commission, Parliament and Council. Similarly to what happens in the EU, though, a single member holds a rotational presidency.

Individual ASEAN Countries, like Vietnam and Singapore, have recently entered into free trade agreements with the European Union, whilst the entire ASEAN block had and still has in place the so-called “plus one” agreements with other regional Countries, namely The People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, The Republic of Korea, India, Japan and Australia and New Zealand together.

With the exception of India, all the other Countries with “plus one” agreements with ASEAN are now part of the RCEP, which will gradually overtake individual FTAs through the harmonisation of rules, especially those related to origin.

RCEP negotiations accelerated with the United States of America’s decision to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) upon the election of President Trump in 2016 (although it is worth noting that a large part of the US Democratic Party also opposed the TPP).

The TPP would have then been the largest free trade agreement ever and, as the name suggest, would have put together twelve nations on the Pacific Ocean, namely Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam, and the USA. With the exclusion of the latter, the other eleven did indeed sign a similar agreement, called Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

The CPTPP has however been ratified only by seven of its signatories and clearly lacks the largest economy and most significant partner of all. At the same time, both the aborted TPP and the CPTPP evidently exclude China.

The RCEP’s weight is therefore self evidently heavier, as it encompasses 2.1 billion people, with its signatories accounting for around 30% of the world’s GDP. And the door for India’s 1.4 billion people and US$2.6 trillion GDP remains open, the other members stated.

Like most FTAs, RCEP’s aim is to lower tariffs, open up trade in goods and services and promote investments. It also briefly covers intellectual property, but makes no mention of environmental protections and labour rights. Its signatories include very advanced economies, like Singapore’s, and quite poor ones, like Cambodia’s.

RCEP’s significance is at this very moment probably more symbolic than tangible. Whilst it is estimated that around 90% of tariffs will be abolished, this will only occur over a period of twenty years after entry into force, which will happen only after ratification. Furthermore, the service industry and even more notably agriculture do not represent the core of the agreement and therefore will still be subject to barriers and domestic rules and restrictions. Nonetheless, it is estimated that, even in these times of pandemic, the RCEP will contribute some US$40billion more, annually, to the world’s GDP, than the CPTPP does (US$186billion vis-à-vis US$147billion) for ten consecutive years.

Its immediate impact is geopolitical. Whilst signatories are not exactly best friends with each other (think of territorial disputes over the South China Sea, for instance), the message is clear:

- The majority of this part of the world has tackled the Covid-19 pandemic remarkably well, but cannot afford to open its borders to Europeans and Americans any time soon, lest the virus spread again. Therefore, it has to try and iron out internal tensions, if it wants to see some positive signs within its economies given by private trade, in addition to (not always good) deficit spending by the State. Most of these Countries do rely heavily on Western talents, tourists, goods, services and even strategic and military support, but they are realistic about the fact that, unless the much touted vaccine works really well really soon, the West will struggle with this coronavirus for many months, if not years.

- Multilateralism is key and isolationism is dangerous. The ASEAN bloc and the Australia-New Zealand duo work exactly in this peaceful and pro-business direction.

The ASEAN’s official website (https://asean.org/?static_post=rcep-regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership) is very clear in this regard and states, in fact that:

RCEP will provide a framework aimed at lowering trade barriers and securing improved market access for goods and services for businesses in the region, through:

- Recognition to ASEAN Centrality in the emerging regional economic architecture and the interests of ASEAN’s FTA partners in enhancing economic integration and strengthening economic cooperation among the participating countries;

- Facilitation of trade and investment and enhanced transparency in trade and investment relations between the participating countries, as well as facilitation of SMEs‘ engagements in global and regional supply chains; and

- Broaden and deepen ASEAN’s economic engagements with its FTA partners.

RCEP recognises the importance of being inclusive, especially to enable SMEs leverage on the agreement and cope with challenges arising from globalisation and trade liberalisation. SMEs (including micro-enterprises) make up more than 90% of business establishments across all RCEP participating countries and are important to every country’s endogenous development of their respective economy. At the same time, RCEP is committed to provide fair regional economic policies that mutually benefit both ASEAN and its FTA partners.

Still, the timing is right also for EU businesses. As mentioned, the EU has in place FTAs with Singapore, South Korea, Vietnam, an Economic Partnership Agreement with Japan, and is negotiating separately with both Australia and New Zealand.

Generally, all these agreements create common rules for all the players involved, thus making it is simpler for companies to trade in different territories. With caveats on entry into force and rules of origin, Countries that have signed both an FTA with the EU and the RCEP, notably Singapore, a major English speaking hub, that ranks first in East Asia in the Rule of Law index (third in the region after New Zealand and Australia and twelfth worldwide: https://worldjusticeproject.org/sites/default/files/documents/Singapore%20-%202020%20WJP%20Rule%20of%20Law%20Index%20Country%20Press%20Release.pdf), could bridge both regions and facilitate global trade even during these challenging times.

Under French law, terms of payment of contracts of sale or of services (food excluded) are strictly regulated (art. L441-10.I Commercial code) as follows:

- Unless otherwise agreed between the parties, the standard time limit for settling the sums due may not exceed 30 days.

- Parties can agree on a time of payment which cannot exceed 60 days after the date of the invoice.

- By way of derogation, a maximum period of 45 days from end of the month after the date of the invoice may be agreed between the parties, provided that this period is expressly stipulated by contract and that it does not constitute a blatant abuse with respect to the creditor (e.g. could be in fact up to 75 days after date of issuance).

The types of international contracts concluded with a French party can be:

(a) An international sales contract governed by French law (or to the national law of a country where CISG is in force), and which does not contractually exclude the Vienna Convention of 1980 on the International Sale of Goods (CISG)

In this case the parties may be freed from the domestic mandatory payment time limits, by virtue of the superiority of CISG over French domestic rules, as stated by public authorities,

(b) An international contract (sale, service or otherwise) concluded by a French party with a party established in the European Union and governed by the law of this other European State,

In this case the parties could be freed from the French domestic mandatory payment time limits, by invoking the rules of this member state law, in accordance with the EU directive 2011/7;

(c) Other international contracts not belonging to (a) or (b),

In these cases the parties might be subject to the French domestic mandatory payment maximum ceilings, if one considers that this rule is an OMR (but not that clearly stated).

Can a foreign party (a purchaser) agree with a French party on time limit of payment exceeding the French mandatory maximum ceilings (for instance 90 days)?

This provision is a public policy rule in domestic contracts. Failing to comply with the payment periods provided for in this article L. 441-10, any trader is liable to an administrative fine, up to a maximum amount of € 75,000 for a natural person and € 2,000,000 for a company. In the event of reiteration the maximum of the fine is raised to € 150,000 for a natural person and € 4,000,000 for a legal person.

There is no express legal special derogatory rule for international contracts (except one very limited to specific intra UE import / export trading). This being said, the French administration (that is to say the Government, the French General Competition and Consumer protection authority, “DGCCRF” or the Commission of examination of the commercial practices, “CEPC”) shows a certain embarrassment for the application of this rule in an international context because obviously it is not suitable for international trade (and is even counterproductive for French exporters).

International sales contract can set aside the maximum payment ceilings of article L441-10.I

Indeed, the Government and the CEPC have identified a legal basis authorizing French exporters to get rid of the maximum time limit imposed by the French commercial code: this is the UN Convention on the international sale of goods of 1980 (aka “CISG”) applying to contracts of supply of (standard or tailor-made) goods (but not services). They invoked the fact that CISG is an international treaty which is a higher standard than the internal standards of the Civil Code and the Commercial Code: it is therefore necessary to apply the CISG instead of article L441-10 of the Commercial Code.

- In the 2013 ministerial response, (supplemented by another one in 2014) the Ministry of Finance was very clear: „the default application of the CISG rules […] therefore already allows French traders to grant their foreign customers payment terms similar to those offered by their international competitors”.

- In its Statement of 2016 (n°16.12), the CEPC went a little further in the reasoning by specifying that CISG poses as a rule that payment occurs at the time of the delivery of the goods, except otherwise agreed by the parties (art. 58 & 59), but does not give a maximum ceiling. According to this Statement, it would therefore be possible to justify that the maximum limit of the Commercial Code be set aside.

The approach adopted by the Ministry of Finance and by the CEPC (which is a kind of emanation of this Ministry) seems to be a considerable breach in which French exporters and their foreign clients can plunge into. This breach is all the easier to use since CISG applies by default as soon as a sales contract is subject to French law (either by the express choice of the parties, or by application of the conflict of law rules by the judge subsequently seized). In other words, even if controls were to be carried out by the French administration on contracts which do not expressly target the CISG, it would be possible to invoke this “CISG open door”.

This ground seems also to be usable as soon as the international sale contract is governed by the national law of a foreign country … which has also ratified CISG (94 countries). But conversely, if the contract expressly excludes the application of CISG, the solution proposed by the administration will close.

For other international contracts not governed by CISG, is this article L441-10.I an overriding mandatory rule in the international context?

The answer is ambiguous. The issue at stake is: if art. L441-10 is an overriding mandatory rule (“OMR”), as such it would still be applied by a French Judge even if the contract is subject to foreign law.

Again the Government and the CEPC took a stance on this issue, but not that clear.

- In its 2013 ministerial response, the Ministry of Finance statement was against the OMR qualification when he referred to «foreign internal laws less restrictive than French law [that] already allows French traders to grant their foreign customers payment terms similar to those offered by their international competitors”.

- The CEPC made another Statement in 2016 (n°1) to know whether or not these ceilings are OMRs in international contracts. A distinction should be made as regards the localization of the foreign party:

– For intra-EU transactions, the CEPC put into perspective these maximum payment terms with the 2011/7 EU directive on the harmonization of payment terms which authorizes other European countries to have terms of payment exceeding 60 days (art 3 §5). Therefore article L441-10.I could not be seen as OMR because it would conflict with other provisions in force in other European countries, also respecting the EU directive which is a higher standard than the French Commercial Code.

– For non intra EU transactions, CEPC seems to consider article L441-10.I as an OMR but the reasoning was not really strong to say straightforwardly that it is per se an OMR.

To conclude on the here above, (except for contracts – sales excluded – concluded with a non-EU party, where the solution is not yet clear), foreign companies may negotiate terms of payment with their French suppliers which are longer than the maximum ceilings set by article L441 – 10, provided that it is not qualified as an abuse of negotiation (to be anticipated in specific circumstances or terms in the contract to show for instance counterparts, on a case by case basis) and having in mind that, with this respect, French case law is still under construction by French courts.

Summary – The Covid-19 emergency has accelerated the transition to e-commerce, both in B2C relationships and in many B2B sectors. Many companies have found themselves operating on the Internet for the first time, shifting their business and customer relationships to the digital world. Unfortunately, it is often the case that attempts at fraud are concealed behind expressions of interest from potential customers. This is particularly the case with new business contacts from China, via email or via the company’s website or social network profiles. Let’s see what the recurrent scams are, small and large, which happen frequently, especially in the world of wine, food, design, and fashion.

What I’m talking about in this post:

- The request for products via the internet from a Chinese buyer

- The legalization of the contract in China, the signature by the Chinese notary public and other expenses

- The modification of payment terms (Man in the mail)

- The false registration of the brand or domain web

- Design and fashion: the phantom e-commerce platform

- The bitcoin and cryptocurrency trader

- How to verify the data of a Chinese company

- How we can help you

Unmissable deal or attempted fraud?

Fortunately, the bad guys in China (and not only: this kind of scams are often perpetrated also by criminals from other countries) are not very creative and the types of scams are well known and recurrent: let’s see the main ones.

The invitation to sign the contract in China

The most frequent case is that of a Chinese company that, after having found information about the foreign products through the website of the company, communicates by email the willingness to purchase large quantities of the products.

This is usually followed by an initial exchange of correspondence via email between the parties, at the outcome of which the Chinese company communicates the decision to purchase the products and asks to finalize the agreement very quickly, inviting the foreign company to go to China to conclude the negotiation and not let the deal fade away.

Many believe it and cannot resist the temptation to jump on the first plane: once landed in China the situation seems even more attractive, since the potential buyer proves to be a very surrendering negotiator, willing to accept all the conditions proposed by the foreign party and hasty to conclude the contract.

This is not a good sign, however: it must sound like a warning.

It is well known that the Chinese are skillful and very patient negotiators, and commercial negotiations are usually long and nerve-wracking: a negotiation that is too easy and fast, especially if it is the first meeting between the parties, is very suspicious.

That you are faced with an attempted scam is then certified by the request for some payments in China, allegedly necessary for the deal.

There are several variants of this first scheme.

The most common are the request to pay a fee for the registration of the contract with a Chinese notary public; a fee for administrative or customs duties; a cash payment for costs of licenses or import permits for the goods, the offer of lunches or dinners to potential business partners (at inflated prices), the stay in a hotel booked by the Chinese side, followed by the surprise of an exorbitant bill.

Back home, unfortunately, very often the signed contract will remain a useless piece of paper, the phantom client will become unavailable and the Chinese company never return the emails or calls of the foreign client. You will then have the certainty that the entire operation was designed with the sole purpose of extorting the unwary foreigner a few thousand euros.

The same scheme (i.e. the commercial order followed by a series of payment requests) can also be carried out online, for reasons similar to those indicated: the clues of the scam are always the contact by a stranger for a very high value order, a very quick negotiation with a request to conclude the deal in a short time and the need to make some payment in advance before concluding the contract.

Payment to a different bank account

Another very frequent scam is the bank account scam which is different from the one usually used.

Here the parts are usually reversed. The Chinese company is the seller of the products, from which the foreign entrepreneur intends to buy or has already bought a number of products.

One day the seller or the agent of reference informs the buyer that the bank account normally used has been blocked (the most frequent excuses are that the authorized foreign currency limit has been exceeded, or administrative checks are in progress, or simply the bank used has been changed), with an invitation to pay the price on a different current account, in the name of another person or company.

In other cases, the request is motivated by the fact that the products will be supplied through another company, which holds the export license for the products and is authorized to receive payments on behalf of the seller.

After making the payment, the foreign buyer receives the bitter surprise: the seller declares they never received the payment, that the different bank account does not belong to the company and that the request for payment to another account came from a hacker who intercepted the correspondence between the parties.

Only then, by verifying the email address from which the request for use of the new account was sent, the buyer generally sees some small difference in the email account used for the payment request on the different account (e.g. different domain name, different provider or different username).

The seller will then only be willing to ship the goods on condition that the payment is renewed on the correct bank account, which – obviously – one should not do, to avoid being deceived a second time. Verification of the owner of the false bank account generally does not lead to any response from the bank and it will in fact be impossible to identify the perpetrators of the scam.

The scam of the fake Chinese Trademark Agent

Another classic Chinese scam is the sending of an email informing the foreign company that a Chinese person intends to register a trademark or a web domain identical to that of the foreign company.

The sender is a self-proclaimed Chinese agency in the sector, which communicates its willingness to intervene and avert the danger, blocking the registration, provided that it is done in a very short time and the foreigner pay the service in advance.

In this case too we are faced with a clumsy attempt at fraud: better to trash the email immediately.

By the way: If you haven’t registered your trademark in China, you should do so right now. If you are interested in learning more about it, you can read this post.

Designers and fashion products: the phantom Chinese e- commerce platform

A widespread scam is the one involving designers and companies in the fashion industry: also in this case the contact arrives through the website or the social media account of the company and expresses a great interest in importing and distributing in China products of the Italian designer or brand.

In the cases that I have dealt with in the past, the proposal is accompanied by a substantial trademark license and distribution contract in English, which provides for the exclusive granting of the trademark and the right to sell the products in China in favor of a Chinese online platform, currently under construction, which will make it possible to reach a very large number of customers.

After signing the contract, the pretexts to extort money from the foreign company are similar to those seen previously: invitation to China and request a series of payments on site, or the need to cover a series of costs to be borne by the Chinese side to start business operations in China for the foreign company: trademark registration, customs requirements, obtaining licenses, etc. (needless to say, all fictional: the platform does not exist, nothing will be done and the contact person will vanish soon after she has received the money).

The bitcoin and cryptocurrency scam

Recently a scam of Chinese origin is the proposal to invest in bitcoin, with a very attractive guaranteed minimum return on investmen (usually 20 or 30%).

The alleged trader presents himself in these cases as a representative of an agency based in China, often referring to a purpose-built website and presentations of investment services made in English.

This scheme usually involves also an international bank, which acts as agent or depository of the sums: in reality, the writer is always the criminal organization, from a bogus account which resembles that of the bank or financial intermediary.

Once the sums are paid the broker disappears and it is not possible to trace the funds because the bank account is closed and the company disappears, or because the payments were made through bitcoin.

The clues of the scam are similar to those seen previously: contact from the Internet or via email, very tempting business proposal, hurry to conclude the agreement and to receive a first payment in China.

How to figure out if we’re dealing with an internet scam

In the cases mentioned above, and in other similar cases, once the scam has been perpetrated there is almost no point in trying to remedy it: the costs and legal fees are usually higher than the money lost and in most cases it is impossible to trace the person responsible for the scam.

Here then is some practical advice – in addition to common sense – to avoid falling into traps similar to those described

How to verify the data of a Chinese company

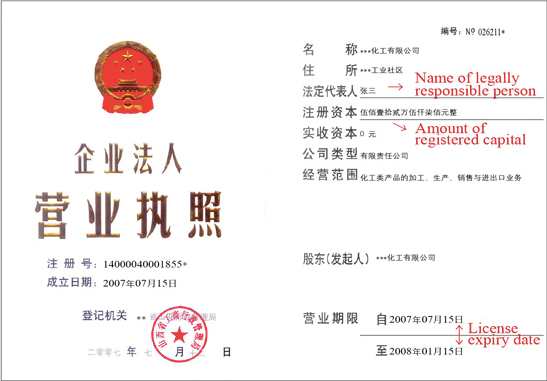

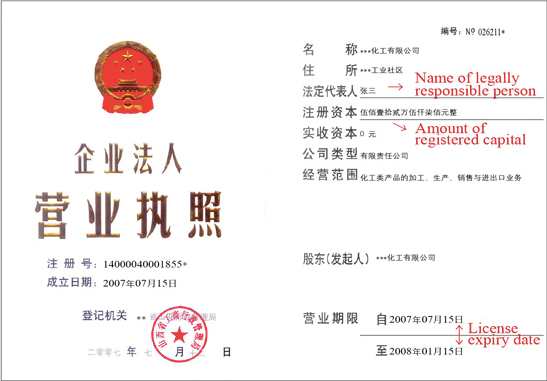

The name of the company in Latin characters and the website in English have no official value, they are just fancy translations: the only way to verify the data of a Chinese company, and to know the people who represent it (or say they do) is to check out the original business license through the online portal of the SAIC (State Administration for Industry and Commerce).

Each Chinese company has in fact a business license issued by SAIC, which contains the following information:

- official company name in Chinese characters;

- registration number;

- registered office;

- company object;

- date of incorporation and expiry;

- legal representative;

- registered and paid-up capital.

It is a Chinese language document, similar to the following:

Verifying the information, with the help of a competent lawyer, will make it possible to ascertain whether or not the company exists, the reliability of the company and whether the self-styled representative can actually act on behalf of the company.

Ask for commercial references

Regardless of whether the Chinese company is interested in importing Italian wine, French fashion or design or other foreign products, an easy check to do is to ask a list international companies with which the Chinese party has previously worked, to validate the information received.

In most cases, the Chinese side will oppose giving references for reasons of privacy, which confirms the suspicion that in reality such phantom success stories do not exist and this is an attempt at fraud.

Manage payments carefully

Having positively marked the first points, it is still advisable to proceed with great caution, especially in the case of a new customer or supplier.

In the case of the sale of products to a Chinese buyer, it is advisable to ask for an advance payment and for the balance of the price when the goods are ready, or the opening of a letter of credit.

In case the Chinese party is the supplier, it is recommended to provide for an on-site inspection of the goods, with a third party to certify the quality of the products and the compliance with the contractual specifications.

Verify requests to change payment methods

If a business relationship is already in progress and you are asked to change the method of payment of the price, you should carefully verify the identity and email account of the applicant and for security it is good to ask for confirmation of the instruction also through other channels of communication (writing to another person in the company, by phone or sending a message via wechat).

How we can help you

Legalmondo offers the possibility to work with a specialized lawyer to examine your need or assist you in the drafting of a contract or contract negotiations with China.

Photo by Andy Beales on Unsplash.

Summary: Since 12 July 2020, new rules apply for platform service providers and search engine operators – irrespective of whether they are established in the EU or not. The transition period has run out. This article provides checklists for platform service providers and search engine operators on how to adapt their services to the Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 on the promotion of fairness and transparency for commercial users of online intermediation services – the P2B Regulation.

The P2B Regulation applies to platform service providers and search engine operators, wherever established, provided only two conditions are met:

(i) the commercial users (for online intermediation services) or the users with a company website (for online search engines) are established in the EU; and

(ii) the users offer their goods/services to consumers located in the EU for at least part of the transaction.

Accordingly, there is a need for adaption for:

- Online intermediation services, e.g. online marketplaces, app stores, hotel and other travel booking portals, social media, and

- Online search engines.

The P2B Regulation applies to platforms in the P2B2C business in the following constellation (i.e. pure B2B platforms are exempt):

Provider -> Business -> Consumer

The article follows up on the introduction to the P2B Regulation here and the detailed analysis of mediation as method of dispute resolution here.

Checklist how to adapt the general terms and conditions of platform services

Online intermediation services must adapt their general terms and conditions – defined as (i) conditions / provisions that regulate the contractual relationship between the provider of online intermediation services and their business users and (ii) are unilaterally determined by the provider of online intermediation services.

The checklist shows the new main requirements to be observed in the general terms and conditions (“GTC”):

- Draft them in plain and intelligible language (Article 3.1 a)

- Make them easily available at any time (also before conclusion of contract) (Article 3.1 b)

- Inform on reasons for suspension / termination (Article 3.1 c)

- Inform on additional sales channels or partner programs (Article 3.1 d)

- Inform on the effects of the GTC on the IP rights of users (Article 3.1 e)

- Inform on (any!) changes to the GTC on a durable medium, user has the right of termination (Article 3.2)

- Inform on main parameters and relative importance in the ranking (incl. possible influence of remuneration), without algorithms or business secrets (Article 5.1, 5.3, 5.5)

- Inform on the type of any ancillary goods/services offered and any entitlement/condition that users offer their own goods/services (Article 6)

- Inform on possible differentiated treatment of goods / services of the provider or individual users towards other users (Article 7.1, 7.2, 7.3)

- No retroactive changes to the GTC (Article 8a)

- Inform on conditions under which users can terminate contract (Article 8b)

- Inform on available or non-available technical and contractual access to information that the Service maintains after contract termination (Article 8c)

- Inform on technical and contractual access or lack thereof for users to any data made available or generated by them or by consumers during the use of services (Article 9)

- Inform on reasons for possible restrictions on users to offer their goods/services elsewhere under other conditions („best price clause“); reasons must also be made easily available to the public (Article 10)

- Inform on access to the internal complaint-handling system (Article 11.3)

- Indicate at least two mediators for any out-of-court settlement of disputes (Article 12)

These requirements – apart from the clear, understandable language of the GTC, their availability and the fundamental ineffectiveness of retroactive adjustments to the GTC – clearly go beyond what e.g. the already strict German law on general terms and conditions requires.

Checklist how to adapt the design of platform services and search engines

In addition, online intermediation services and online search engines must adapt their design and, among other things, introduce internal complaint-handling. The checklist shows the main design requirements for:

a) Online intermediation services

- Make identity of commercial user clearly visible (Article 3.5)

- State reasons for suspension / limitation / termination of services (Article 4.1, 4.2)

- Explain possible differentiated treatment of goods / services of providers themselves or users in relation to other users (Article 7.1, 7.2, 7.3), see above

- Set an internal complaint handling system, with publicly available info, annual updates (Article 11, 4.3)

b) Online search engines

- Explain the ranking’s main parameters and their relative importance, public, easily available, always up to date (incl. possible influence of remuneration), without algorithms or trade secrets (Article 5.2, 5.3, 5.5)

- If ranking changes or delistings occur due to notification by third parties: offer to inspect such notification (Article 5.4)

- Explain possible differentiated treatment of goods / services of providers themselves or users in relation to other users (Article 7.1, 7.2, 7.3)

The European Commission will provide guidelines regarding the ranking rules in Article 5, as announced in the P2B Regulation – see the overview here. At the same time, providers of online intermediation services and online search engines shall draw up codes of conduct together with their users.

Practical Tips

- The Regulation significantly affects contractual freedom as it obliges platform services to adapt their general terms and conditions.

- The Regulation is to be enforced by „representative organisations“ or associations and public bodies, with the EU Member States ensuring adequate and effective enforcement. The European Commission will monitor the impact of the Regulation in practice and evaluate it for the first time on 13.01.2022 (and every three years thereafter).

- The P2B Regulation may affect distribution relationships, in particular platforms as distribution intermediaries. Under German distribution law, platforms and other Internet intermediation services acting as authorised distributors may be entitled to a goodwill indemnity at termination (details here) if they disclose their distribution channels on the basis of corresponding platform general terms and conditions, as the Regulation does not require, but at least allows to do (see also: Rohrßen, ZVertriebsR 2019, 341, 344–346). In addition, there are numerous overlaps with antitrust, competition and data protection law.

Summary – According to French case law, an agent is subject to the protection of the commercial agent legal status and therefor is entitled to a termination indemnity only if it has the power to negotiate freely the price and terms of the sale contracts. ECJ ruled recently that such condition is not compliant with European law. However, principals could now consider other options to limit or exclude the termination indemnity.

It is an understatement to say that the ruling of the European court of justice of June 4, 2020 (n°C828/18, Trendsetteuse / DCA) was expected by both French agents and their principals.

The question asked to the ECJ

The question asked by the Paris Commercial Court on December 19, 2018 to the ECJ concerned the definition of the status of the commercial agent who could benefit from the EC Directive of December 18, 1986 and consequently of article L134 and seq. of Commercial Code.

The preliminary question consisted in submitting to the ECJ the definition adopted by the Court of Cassation and many Courts of Appeal, since 2008 : the benefit of the status of commercial agent was denied to any agent who does not have, according to the contract and de facto, the power to freely negotiate the price of sale contracts concluded, on behalf of the seller, with a buyer (this freedom of negotiation being also extend to other essential terms of the sale, such as delivery or payment terms).

The restriction ruled by French courts

This approach was criticized because, among other things, it was against the very nature of the economic and legal function of the commercial agent, who has to develop the principal’s activity while respecting its commercial policy, in a uniform manner and in strict compliance with the instructions given. As most of the agency contracts subject to French law expressly exclude the agent’s freedom to negotiate the prices or the main terms of the sales contracts, judges regularly requalified the contract from commercial agency contract into common interest mandate contract. However, this contract of common interest mandate is not governed by the provisions of Articles L 134 et seq. of the Commercial Code, many of which are of internal public order, but by the provisions of the Civil Code relating to the mandate which in general are not considered to be of public order.

The main consequence of this dichotomy of status lays in the possibility for the principal bound by a contract of common interest mandate to expressly set aside the compensation at the end of the contract, this clause being perfectly valid in such a contract, unlike to the commercial agent contract (see French Chapter to Practical Guide to International Commercial Agency Contracts).

The decision of the ECJ and its effect

The ECJ ruling of June 4, 2020 puts an end to this restrictive approach by French courts. It considers that Article 1 (2) of Directive of December 18, 1986 must be interpreted as meaning that agents must not necessarily have the power to modify the prices of the goods which they sell on behalf of a principal in order to be classified as a commercial agent.

The court reminds in particular that the European directive applies to any agent who is empowered either to negotiate or to negotiate and conclude sales contracts. The court added that the concept of negotiation cannot be understood in the restrictive lens adopted by French judges. The definition of the concept of „negotiation” must not only take into account the economic role expected from such intermediary (negotiation being very broad: i.e. dealing) but also preserve the objectives of the directive, mainly to ensure the protection of this type of intermediary.

In practice, principals will therefore no longer be able to hide behind a clause prohibiting the agent from freely negotiating the prices and terms of sales contracts to deny the status of commercial agent.

Alternative options to principals

What are the means now available to French or foreign manufacturers and traders to avoid paying compensation at the end of the agency contract?

- First of all, in case of international contracts, foreign principals will probably have more interest in submitting their contract to a foreign law (provided that it is no more protective than French law …). Although commercial agency rules are not deemed to be overriding mandatory rules by French courts (diverging from ECJ Ingmar and Unamar case law), to secure the choice not to be governed by French law, the contract should also better stipulate an exclusive jurisdiction clause to a foreign court or an arbitration clause (see French Chapter to Practical Guide to International Commercial Agency Contracts).

- it is also likely that principal will ask more often a remuneration for the contribution of its (preexisting) clients data base to the agent, the payment of this remuneration being deferred at the end of the contract … in order to compensate, if necessary, in whole or in part, with the compensation then due to the commercial agent.

- It is quite certain that agency contracts will stipulate more clearly and more comprehensively the duties of the agent that the principal considers to be essential and which violation could constitute a serious fault, excluding the right to an end-of-contract compensation. Although judges are free to assess the seriousness of a breach, they can nevertheless use the contractual provisions to identify what was important in the common intention of the parties.

- Some principals will also probably question the opportunity of continuing to use commercial agents, while in certain cases their expected economic function may be less a matter of commercial agency contract, but rather more of a promotional services contract. The distinction between these two contracts must, however, be strictly observed both in their text and in reality, and other consequences would need to be assessed, such as the regime of the prior notice (see our article on sudden termination of contracts)

Finally, the reasoning used by ECJ in this ruling (autonomous interpretation in the light of the context and aim of this directive) could possibly lead principals to question the French case-law rule consisting in granting, almost eyes shut, two years of gross commissions as a flat fee compensation, whereas article 134-12 of Commercial code does not fix the amount of this end-of-contract compensation but merely indicates that the actual damage suffered by the agent must be compensated ; so does article 17.3 of the 1986 EC directive. The question could then be asked whether such article 17.3 requires the agent to prove the damage actually suffered.

It is usually said that “conflict is not necessarily bad, abnormal, or dysfunctional; it is a fact of life[1]” I would perhaps add that quite often conflict is a suitable opportunity to evolve and to solve problems[2]. It is, in fact, a useful part of life[3] and particularly, should I add, of businesses. And conflicts not only arise at the end of the business relationship or to terminate it, but also during it and the parties remain willing to continue it.

The 2008 EU Directive on certain aspects of mediation in civil and commercial matters states that «agreements resulting from mediation are more likely to be complied with voluntarily and are more likely to preserve an amicable and sustainable relationship between the parties.»

Can, therefore, mediation be used not only as an alternative to court or arbitration when terminating distribution agreements, but also to re-organize them or to change contract conditions? Would it be useful to solve these conflicts? What could be the advantages?

In distribution/agency/franchise agreements, particularly for those lasting several years, parties can have neglected their obligations (for instance minimum sales targets not attained).

Sometimes they could have tolerated the situation although they remain not very happy with the other party’s performance because they are still doing acceptable business.

It could also happen that one of the parties wishes to restructure the entire distribution network (Can we change the distribution structure to an agency one?), but does not want to face a complete termination because there are other benefits in the relationship.

There may be just some changes to be introduced, or changes in the legal structures (A mere reseller transformed in distributor?), legal frameworks, legal conditions (Which one is the applicable law?), limitation of the scope of contract, territory…

And now, we face the Covid-19 crisis where everything is still more uncertain.

In some cases, it could happen that there is no written contract and the parties wish to draft it; in other cases, agreements could have been defectively drafted with incomplete, contradictory or no regulation at all (Was it an exclusive agreement?).

The contracts could be perfect for the situation imagined when signed several years ago but not anymore (What happen with online sales?) or circumstances, markets, services, products have changed and need to be reconsidered (mergers, change of directors…).

Sometimes, even more powerful parties have not the elements to oblige the weaker party to respect new terms, or they simply prefer not to impose their conditions, but to build up a more collaborative relationship for the future.

In all these cases, negotiation is the usual strategy parties follow: each one is focused in obtaining its own benefits with a clear idea of, for instance, which clause(s) should be modified or drafted.

Nevertheless, mediation could add some neutrality, and some space to a more efficient, structured and useful approach to the modification of the commercial relationship, particularly in distribution agreements where the collaboration (in the past, but also in the future if the parties wish so) is of paramount importance.

In most of these situations, personal emotional aspects could also be involved and make more difficult a neutral negotiation: a distributor that has been seen by the manufacturer as not performing very well and feels hurt, an agent that could consider a retirement, parties from different cultures that need to understand different ways of performing, franchisees that have been treated differently in the network and feel discriminated, etc.

In these circumstances and in other similar ones, where all persons involved, assisted by their respective lawyers, wish to continue the relationship although maybe in a different way, a sort of facilitative mediation can be a great help.

These are, in my opinion, the main reasons:

- Mediation is a legal and organized procedure that could help the parties to increase their awareness of the necessity to redraft the agreement (or drafting for the first time if it was not already done).

- Parties can be heard more easily, negotiation is eased in the interest of both of them, encourages them to act more reasonably vis-à-vis the other side, restores relationship if necessary, deadlock can be easily broken and, if the circumstances advice so, parties can be engaged separately with the help of the mediator.

- Mediation can consider other elements different to the mere commercial or legal ones: emotions linked to performance, personal situations (retirement, succession, illness) or even differences in cultural approaches.

- It helps to find the real (possibly new or not shown) interests in the commercial relationship of the parties, focusing in developments, strategies, new proposals… The mere negotiation between the parties and they attorneys could not make appear these new interests and therefore be limited only to the discussion on the change of concrete obligations, clauses or situations. Mediation helps to go beyond.

- Mediation techniques can also help the parties to face their current situation, to take responsibility of their performance without focusing on blame or incompetence but on a constructive and future collaboration in new specific terms.[4]

- It can also avoid the increasing of the conflict into a more severe one (breaching) and in case mediation does not end with a new/redrafted agreement, the basis for a mediated termination can be established, if the parties wish so, instead of litigation.

- Mediation can conclude into a new agreement where the parties are more reassured, more comfortable with, and more willing to respect because they were involved in their construction with the assistance of their respective lawyers, and because all their interests (not only new drafted clauses) were considered.

- And, in any case, mediation does not affect the party’s collaborative position and does not reduce their possibility to use other alternatives, including litigation or arbitration to terminate the agreement or to oblige the other party to respect its legal obligations.

The use of mediation does not need the parties to have foreseen it in the agreement (although it could be easier if they did so) but they can use it freely at any time.

This said, a lawyer proposing mediation as a contractual clause or, in case it was not included in the agreement, as a procedure to face this sort of conflicts in distribution agreements, will be certainly seen by his/her client as problem-solving attorney looking for the client’s interests rather than a litigator pushing them to a more uncertain situation, with unknown costs and unforeseeable timeframe.

Parties in distribution agreements should have this possibility in mind and lawyers have the opportunity to actively participate in mediation from the first steps by recommending it in the initial agreement, during the process helping the clients to express their concerns and interests, and in the drafting of the final (new) agreement, representing the clients’ and as co-author of their success.

If you would like to hear more on the topic of mediation and distribution agreements you can check out the recording of our webinar on Mediation in International Conflicts

[1] Moore, Christopher W. The Mediation Process: Practical Strategies for Resolving Conflict. Jossey-Bass. Wiley, 2014.

[2] Mnookin, Robert H. Beyond Winning. Negotiating to create value in deals and disputes (p. 53). Harvard University Press, 2000.

[3] Fisher, R; Ury, W. Getting to Yes: Negotiating an agreement without giving in. Random House.

[4] «Talking about blame distracts us from exploring why things went wrong and how we might correct them going forward. Focusing instead on understanding the contribution system allows us to learn about the real causes of the problem, and to work on correcting them.» [Stone, Douglas. “Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most”. Penguin Publishing Group]

Quick Summary: In Germany, on termination of a distribution contract, distribution intermediaries (especially distributors / franchisees) may claim an indemnity from their manufacturer / supplier if their position is similar to that of commercial agents. This is the case if the distribution intermediary is integrated into the supplier’s sales organization and obliged to transfer its customer base to the supplier, i.e. to transmit its customer data, so that the supplier can immediately and without further ado make use of the advantages of the customer base at the end of the contract. A recent court decision now aims at extending the distributor’s right to indemnity also to cases where the supplier in any way benefited from the business relationship with the distributor, even where the distributor did not provide the customer data to the supplier. This article explains the situation and gives tips on how to overcome the ambiguity that this new decision brings with it.

A German court has recently widened the distributor’s right to goodwill indemnity at termination: Suppliers might even have to pay indemnity if the distributor was not obliged to transfer the customer base to the supplier. Instead, any goodwill provided could suffice – understood as substantial benefits the supplier can, after termination, derive from the business relationship with the distributor, regardless of what the parties have stipulated in the distribution agreement.

The decision may impact all businesses where products are sold through distributors (and franchisees, see below) – particularly in retail (especially for electronics, cosmetics, jewelry, and sometimes fashion), car and wholesale trade. Distributors are self-employed, independent contractors who sell and promote the products

- on a regular basis and in their own name (differently from commercial agents),

- on their own account (differently from commission agents),

- thus bearing the sales risk, for which – in return – their margins are rather high.

Under German law, distributors are less protected than commercial agents. However, even distributors and commission agents (see here) are entitled to claim indemnity at termination if two prerequisites are given, namely if the distributor or the commission agent is

- integrated into the supplier’s sales organization (more than a pure reseller); and

- obliged (contractually or factually) to forward customer data to the supplier during or at termination of the contract (German Federal Court, 26 November 1997, Case No. VIII ZR 283/96).

Now, the Regional Court of Nuremberg-Fürth has established that the second prerequisite shall already be fulfilled if the distributor has provided the supplier with goodwill:

“… the only decisive factor, in the sense of an analogy, is whether the defendant (the principal) has benefited from the business relationship with the plaintiff (distributor). …

… the principal owes an indemnity if he has a „goodwill“, i.e. a justified profit expectation, from the business relationships with customers created by the distributor.”

(Decision of 27 November 2018, Case no. 2 HK O 10103/12).

To support this wider approach, the court abstractly referred to the opinion by the EU advocate general in the case Marchon/Karaszkiewicz, rendered on 10 September 2015. That case, however, did not concern distributors, but the commercial agent’s entitlement to an indemnity, specifically the concept of “new customers” under the Commercial Agency Directive 86/653/EEC.

In the present case, it would, according to the court, suffice that the supplier had the data on the customers generated by the distributor on his computer and could freely make use of them. Other cases where the distributor indemnity might arise, even regardless of the concrete customer data, would be cases where the supplier takes over the store from the distributor, with the consequence of customers continuing to visit the very store also after the distributor has left.

Practical tips:

1. The decision makes the legal situation with distributors / franchisees less clear. The court’s wider approach needs, however, to be seen in the light of the Federal Court’s case law: The court still in 2015 denied a distributor the indemnity, arguing that the second prerequisite was missing, i.e. that the distributor was not obliged to forward the customer data (decision of 5 February 2015, case no. VII ZR 315/13, following its earlier decision re Toyota, 17 April 1996, case no. VIII ZR 5/95). Moreover, the Federal Court also denied franchisees the right to indemnity where the franchise concerns anonymous bulk business and customers continue to be regular customers only de facto (decision of 5 February 2015, case no. VII ZR 109/13 re bakery chain “Kamps”). It remains to be seen how the case law develops.

2. In any case, suppliers should, before entering the German market, consider whether they are willing to take that risk of having to pay indemnity at termination.

3. The same applies to franchisors: franchisees will likely be able to claim indemnity based on analogue application of commercial agency law. Until today, the German Federal Court of Justice has denied the franchisee’s indemnity claim in the single case and therefore left open whether franchisees in general could claim such indemnity (e.g. decision of 23 July 1997, case no. VIII ZR 134/96 re Benetton stores). Nevertheless, German courts could quite likely affirm the claim in the case of distribution franchising (where the franchisee buys the products from the franchisor), provided the situation is similar to distributorship and commercial agency. This could be the case where the franchisee has been entrusted with the distribution of the franchisor’s products and the franchisor alone is entitled, after termination of contract, to access the customers newly acquired by the franchisee during the contract (cf. German Federal Court, decision of 29 April 2010, Case No. I ZR 3/09, Joop). No indemnity, however, can be claimed where

- the franchise concerns anonymous bulk business and customers continue to be regular customers only de facto (decision of 5 February 2015 re the bakery chain “Kamps”);

- or production franchising (bottling contracts, etc.) where the franchisor or licensor is not active in the very sector of products distributed by the franchisee / licensee (decision of 29 April 2010, Case No. I ZR 3/09, Joop).

4. The German indemnity for distributors – or potentially for franchisees – can still be avoided by:

- choosing another law that does not provide for an indemnity;

- obliging the supplier to block, stop using and, if necessary, delete such customer data at termination (German Federal Court, decision of 5 February 2015, case no. VII ZR 315/13: “Subject to the provisions set out in Section [●] below, the supplier shall block the data provided by the distributor after termination of the distributor’s participation in the customer service, cease their use and delete them upon the distributor’s request.„). Though such contractual provision appears to be irrelevant according to the above decision by the Court of Nuremberg, the court does not provide any argument why the established Federal Court’s case law should not apply any more;

- explicitly contracting the indemnity out, which, however, may work only if (i) the distributor acts outside the EEA and (ii) there is no mandatory local law providing for such indemnity (see the article here).

5. Further, if the supplier deliberately accepts to pay the indemnity in return for a solid customer base with perhaps highly usable data (in compliance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation), the supplier can agree with the distributor on “entry fees” to mitigate the obligation. The payment of such entry fees or contract fees could be deferred until termination and then offset against the distributor’s claim for indemnity.

6. The distributor’s goodwill indemnity is calculated on basis of the margins made with new customers brought by the distributor or with existing customers where the distributor has significantly increased the business. The exact calculation can be quite sophisticated and German courts apply different calculation methods. In total, it may amount up to the past years’ average annual margin the distributor made with such customers.

Are insurers liable for breach of the GDPR on account of their appointed intermediaries?

Insurers acting out of their traditional borders through a local intermediary should choose carefully their intermediaries when distributing insurance products, and use any means at their disposal to control them properly. Distribution of insurance products through an intermediary can be a fast way to distribute insurance products and enter a territory with a minimum of investments. However, it implies a strict control of the intermediary’s activities.

The reason is that Insurers in FOS can be held jointly liable with the intermediary if this one violates personal data regulation and its obligations as set by the GDPR (Regulation 2016/679 of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data).

In a decision dated 18 July 2019 , the CNIL (Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés), the French authority in charge of personal data protection rendered a decision against ACTIVE ASSURANCE, a French intermediary, for several breaches of the GDPR. The intermediary was found guilty and fined EUR 180,000 for failing to properly protect the personal data of its clients. Those were found easily accessible on the web by any technician well versed in data processing. Moreover, the personal access codes of the clients were too simple and therefore easily accessible by third parties.

Although in this particular case insurers were not fined by the CNIL, the GDPR considers that they can be jointly liable with the intermediary in case of breach of personal data. In particular, the controller is liable for any acts of the processor he has appointed, this one being considered as a sub-contractor (clauses 24 and 28 of the GDPR).

This illustrates the risks to distribute insurance products through an intermediary without controlling its activities. Acting through intermediaries, in particular for insurance companies acting from foreign EU countries in FOS under the EU Directive on freedom of insurance services (Directive 2016/97 of 20 January 2016 on insurance distribution) requires a strict control through enacting contractual dispositions whereas are defined:

- a clear distribution of the duties between insurer and distributor (who is controller/joint controller/processor ?) as regards technical means used for protecting personal data (who shall do/control what ?) and legal requirements (who must report to the authorities in case of breach of security/ who shall reply to requests from data owners?, etc.);

- the right of the insurer to audit the distributors’ technical means used for this protection at any time during the term of the contract. In addition to this, one should always keep in mind that this audit should be conducted efficiently by the insurer at regular times. As Napoleon rightly said: “You can govern from afar, but you can only administer closely”.

Schreiben Sie an Benedikt

France – ECJ extends the protection of commercial agents and their right to termination indemnity

25 Juli 2020

-

Frankreich

- Agentur

- Vertrieb

Under Vietnam’s presidency of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), after eight years of negotiations, the ten ASEAN member states (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) on 15 November 2020 signed a groundbreaking free trade agreement (FTA) with China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, called Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

The ASEAN economic community is a free trade area kickstarted in 2015 among the above-mentioned ten members of the homonymous association, comprising an aggregate GDP of US$2.6 trillion and over 622 million people. ASEAN is China’s main trading partner, with the European Union now slipping into second place.

Unlike the EuroZone and the European Union, ASEAN does not have a single currency, nor common institutions, like the EU Commission, Parliament and Council. Similarly to what happens in the EU, though, a single member holds a rotational presidency.

Individual ASEAN Countries, like Vietnam and Singapore, have recently entered into free trade agreements with the European Union, whilst the entire ASEAN block had and still has in place the so-called “plus one” agreements with other regional Countries, namely The People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, The Republic of Korea, India, Japan and Australia and New Zealand together.

With the exception of India, all the other Countries with “plus one” agreements with ASEAN are now part of the RCEP, which will gradually overtake individual FTAs through the harmonisation of rules, especially those related to origin.

RCEP negotiations accelerated with the United States of America’s decision to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) upon the election of President Trump in 2016 (although it is worth noting that a large part of the US Democratic Party also opposed the TPP).

The TPP would have then been the largest free trade agreement ever and, as the name suggest, would have put together twelve nations on the Pacific Ocean, namely Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam, and the USA. With the exclusion of the latter, the other eleven did indeed sign a similar agreement, called Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

The CPTPP has however been ratified only by seven of its signatories and clearly lacks the largest economy and most significant partner of all. At the same time, both the aborted TPP and the CPTPP evidently exclude China.

The RCEP’s weight is therefore self evidently heavier, as it encompasses 2.1 billion people, with its signatories accounting for around 30% of the world’s GDP. And the door for India’s 1.4 billion people and US$2.6 trillion GDP remains open, the other members stated.

Like most FTAs, RCEP’s aim is to lower tariffs, open up trade in goods and services and promote investments. It also briefly covers intellectual property, but makes no mention of environmental protections and labour rights. Its signatories include very advanced economies, like Singapore’s, and quite poor ones, like Cambodia’s.

RCEP’s significance is at this very moment probably more symbolic than tangible. Whilst it is estimated that around 90% of tariffs will be abolished, this will only occur over a period of twenty years after entry into force, which will happen only after ratification. Furthermore, the service industry and even more notably agriculture do not represent the core of the agreement and therefore will still be subject to barriers and domestic rules and restrictions. Nonetheless, it is estimated that, even in these times of pandemic, the RCEP will contribute some US$40billion more, annually, to the world’s GDP, than the CPTPP does (US$186billion vis-à-vis US$147billion) for ten consecutive years.

Its immediate impact is geopolitical. Whilst signatories are not exactly best friends with each other (think of territorial disputes over the South China Sea, for instance), the message is clear:

- The majority of this part of the world has tackled the Covid-19 pandemic remarkably well, but cannot afford to open its borders to Europeans and Americans any time soon, lest the virus spread again. Therefore, it has to try and iron out internal tensions, if it wants to see some positive signs within its economies given by private trade, in addition to (not always good) deficit spending by the State. Most of these Countries do rely heavily on Western talents, tourists, goods, services and even strategic and military support, but they are realistic about the fact that, unless the much touted vaccine works really well really soon, the West will struggle with this coronavirus for many months, if not years.

- Multilateralism is key and isolationism is dangerous. The ASEAN bloc and the Australia-New Zealand duo work exactly in this peaceful and pro-business direction.

The ASEAN’s official website (https://asean.org/?static_post=rcep-regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership) is very clear in this regard and states, in fact that:

RCEP will provide a framework aimed at lowering trade barriers and securing improved market access for goods and services for businesses in the region, through:

- Recognition to ASEAN Centrality in the emerging regional economic architecture and the interests of ASEAN’s FTA partners in enhancing economic integration and strengthening economic cooperation among the participating countries;

- Facilitation of trade and investment and enhanced transparency in trade and investment relations between the participating countries, as well as facilitation of SMEs‘ engagements in global and regional supply chains; and

- Broaden and deepen ASEAN’s economic engagements with its FTA partners.

RCEP recognises the importance of being inclusive, especially to enable SMEs leverage on the agreement and cope with challenges arising from globalisation and trade liberalisation. SMEs (including micro-enterprises) make up more than 90% of business establishments across all RCEP participating countries and are important to every country’s endogenous development of their respective economy. At the same time, RCEP is committed to provide fair regional economic policies that mutually benefit both ASEAN and its FTA partners.

Still, the timing is right also for EU businesses. As mentioned, the EU has in place FTAs with Singapore, South Korea, Vietnam, an Economic Partnership Agreement with Japan, and is negotiating separately with both Australia and New Zealand.

Generally, all these agreements create common rules for all the players involved, thus making it is simpler for companies to trade in different territories. With caveats on entry into force and rules of origin, Countries that have signed both an FTA with the EU and the RCEP, notably Singapore, a major English speaking hub, that ranks first in East Asia in the Rule of Law index (third in the region after New Zealand and Australia and twelfth worldwide: https://worldjusticeproject.org/sites/default/files/documents/Singapore%20-%202020%20WJP%20Rule%20of%20Law%20Index%20Country%20Press%20Release.pdf), could bridge both regions and facilitate global trade even during these challenging times.

Under French law, terms of payment of contracts of sale or of services (food excluded) are strictly regulated (art. L441-10.I Commercial code) as follows:

- Unless otherwise agreed between the parties, the standard time limit for settling the sums due may not exceed 30 days.

- Parties can agree on a time of payment which cannot exceed 60 days after the date of the invoice.

- By way of derogation, a maximum period of 45 days from end of the month after the date of the invoice may be agreed between the parties, provided that this period is expressly stipulated by contract and that it does not constitute a blatant abuse with respect to the creditor (e.g. could be in fact up to 75 days after date of issuance).

The types of international contracts concluded with a French party can be:

(a) An international sales contract governed by French law (or to the national law of a country where CISG is in force), and which does not contractually exclude the Vienna Convention of 1980 on the International Sale of Goods (CISG)

In this case the parties may be freed from the domestic mandatory payment time limits, by virtue of the superiority of CISG over French domestic rules, as stated by public authorities,

(b) An international contract (sale, service or otherwise) concluded by a French party with a party established in the European Union and governed by the law of this other European State,

In this case the parties could be freed from the French domestic mandatory payment time limits, by invoking the rules of this member state law, in accordance with the EU directive 2011/7;

(c) Other international contracts not belonging to (a) or (b),

In these cases the parties might be subject to the French domestic mandatory payment maximum ceilings, if one considers that this rule is an OMR (but not that clearly stated).

Can a foreign party (a purchaser) agree with a French party on time limit of payment exceeding the French mandatory maximum ceilings (for instance 90 days)?

This provision is a public policy rule in domestic contracts. Failing to comply with the payment periods provided for in this article L. 441-10, any trader is liable to an administrative fine, up to a maximum amount of € 75,000 for a natural person and € 2,000,000 for a company. In the event of reiteration the maximum of the fine is raised to € 150,000 for a natural person and € 4,000,000 for a legal person.

There is no express legal special derogatory rule for international contracts (except one very limited to specific intra UE import / export trading). This being said, the French administration (that is to say the Government, the French General Competition and Consumer protection authority, “DGCCRF” or the Commission of examination of the commercial practices, “CEPC”) shows a certain embarrassment for the application of this rule in an international context because obviously it is not suitable for international trade (and is even counterproductive for French exporters).

International sales contract can set aside the maximum payment ceilings of article L441-10.I

Indeed, the Government and the CEPC have identified a legal basis authorizing French exporters to get rid of the maximum time limit imposed by the French commercial code: this is the UN Convention on the international sale of goods of 1980 (aka “CISG”) applying to contracts of supply of (standard or tailor-made) goods (but not services). They invoked the fact that CISG is an international treaty which is a higher standard than the internal standards of the Civil Code and the Commercial Code: it is therefore necessary to apply the CISG instead of article L441-10 of the Commercial Code.

- In the 2013 ministerial response, (supplemented by another one in 2014) the Ministry of Finance was very clear: „the default application of the CISG rules […] therefore already allows French traders to grant their foreign customers payment terms similar to those offered by their international competitors”.

- In its Statement of 2016 (n°16.12), the CEPC went a little further in the reasoning by specifying that CISG poses as a rule that payment occurs at the time of the delivery of the goods, except otherwise agreed by the parties (art. 58 & 59), but does not give a maximum ceiling. According to this Statement, it would therefore be possible to justify that the maximum limit of the Commercial Code be set aside.

The approach adopted by the Ministry of Finance and by the CEPC (which is a kind of emanation of this Ministry) seems to be a considerable breach in which French exporters and their foreign clients can plunge into. This breach is all the easier to use since CISG applies by default as soon as a sales contract is subject to French law (either by the express choice of the parties, or by application of the conflict of law rules by the judge subsequently seized). In other words, even if controls were to be carried out by the French administration on contracts which do not expressly target the CISG, it would be possible to invoke this “CISG open door”.

This ground seems also to be usable as soon as the international sale contract is governed by the national law of a foreign country … which has also ratified CISG (94 countries). But conversely, if the contract expressly excludes the application of CISG, the solution proposed by the administration will close.

For other international contracts not governed by CISG, is this article L441-10.I an overriding mandatory rule in the international context?

The answer is ambiguous. The issue at stake is: if art. L441-10 is an overriding mandatory rule (“OMR”), as such it would still be applied by a French Judge even if the contract is subject to foreign law.

Again the Government and the CEPC took a stance on this issue, but not that clear.

- In its 2013 ministerial response, the Ministry of Finance statement was against the OMR qualification when he referred to «foreign internal laws less restrictive than French law [that] already allows French traders to grant their foreign customers payment terms similar to those offered by their international competitors”.

- The CEPC made another Statement in 2016 (n°1) to know whether or not these ceilings are OMRs in international contracts. A distinction should be made as regards the localization of the foreign party:

– For intra-EU transactions, the CEPC put into perspective these maximum payment terms with the 2011/7 EU directive on the harmonization of payment terms which authorizes other European countries to have terms of payment exceeding 60 days (art 3 §5). Therefore article L441-10.I could not be seen as OMR because it would conflict with other provisions in force in other European countries, also respecting the EU directive which is a higher standard than the French Commercial Code.

– For non intra EU transactions, CEPC seems to consider article L441-10.I as an OMR but the reasoning was not really strong to say straightforwardly that it is per se an OMR.

To conclude on the here above, (except for contracts – sales excluded – concluded with a non-EU party, where the solution is not yet clear), foreign companies may negotiate terms of payment with their French suppliers which are longer than the maximum ceilings set by article L441 – 10, provided that it is not qualified as an abuse of negotiation (to be anticipated in specific circumstances or terms in the contract to show for instance counterparts, on a case by case basis) and having in mind that, with this respect, French case law is still under construction by French courts.

Summary – The Covid-19 emergency has accelerated the transition to e-commerce, both in B2C relationships and in many B2B sectors. Many companies have found themselves operating on the Internet for the first time, shifting their business and customer relationships to the digital world. Unfortunately, it is often the case that attempts at fraud are concealed behind expressions of interest from potential customers. This is particularly the case with new business contacts from China, via email or via the company’s website or social network profiles. Let’s see what the recurrent scams are, small and large, which happen frequently, especially in the world of wine, food, design, and fashion.

What I’m talking about in this post:

- The request for products via the internet from a Chinese buyer

- The legalization of the contract in China, the signature by the Chinese notary public and other expenses

- The modification of payment terms (Man in the mail)

- The false registration of the brand or domain web

- Design and fashion: the phantom e-commerce platform

- The bitcoin and cryptocurrency trader

- How to verify the data of a Chinese company

- How we can help you

Unmissable deal or attempted fraud?

Fortunately, the bad guys in China (and not only: this kind of scams are often perpetrated also by criminals from other countries) are not very creative and the types of scams are well known and recurrent: let’s see the main ones.

The invitation to sign the contract in China

The most frequent case is that of a Chinese company that, after having found information about the foreign products through the website of the company, communicates by email the willingness to purchase large quantities of the products.

This is usually followed by an initial exchange of correspondence via email between the parties, at the outcome of which the Chinese company communicates the decision to purchase the products and asks to finalize the agreement very quickly, inviting the foreign company to go to China to conclude the negotiation and not let the deal fade away.

Many believe it and cannot resist the temptation to jump on the first plane: once landed in China the situation seems even more attractive, since the potential buyer proves to be a very surrendering negotiator, willing to accept all the conditions proposed by the foreign party and hasty to conclude the contract.

This is not a good sign, however: it must sound like a warning.

It is well known that the Chinese are skillful and very patient negotiators, and commercial negotiations are usually long and nerve-wracking: a negotiation that is too easy and fast, especially if it is the first meeting between the parties, is very suspicious.

That you are faced with an attempted scam is then certified by the request for some payments in China, allegedly necessary for the deal.

There are several variants of this first scheme.