-

Italien

Made in Italy: protection of trademarks of special national interest and value

29 Januar 2025

- Geistiges Eigentum

- Markenzeichen und Patente

‘’Made in Italy” is synonymous of high productive and aesthetic quality and represents an added value, in the international market, for different kind of products, from foodstuffs to clothing, automotive and furniture. In recent years, in Italy, a number of initiatives have been taken at the regulatory level to ensure its promotion, valorization and protection.

In 2024 came into force law no. 206/2023, referred to as the ‘New Made in Italy Law’, followed on 3 July 2024 by the related implementing Decree, by which the Ministry of Enterprise and Made in Italy (hereinafter the ‘Ministry’) introduced relevant provisions including the ones related to an official mark attesting the Italian origin of goods, the fight against counterfeiting (in particular in criminal law), and the promotion of the use of blockchain technology to protect production chains.

Among the new measures, there are specific rules for the protection of trademarks – with at least 50 years of registration or use in Italy – of particular national interest and value (hereinafter “Trademark/s”). The aim of such provisions is to safeguard the heritage represented by Italian trademarks with a long-standing presence on the market, preventing their extinction and guaranteeing their use by companies linked to the Italian territory.

Measures to guarantee the continuity

In order to protect the Trademarks, two distinct possibilities are envisaged

- Notification by companies

The first consists of the takeover by the Ministry of the ownership of Trademarks of companies that will cease their activities. In this regard, the Decree provides that a company owner or licensee of a trademark registered for at least 50 years, or for which it is possible to prove continuous use for at least 50 years, intending to cease its activity definitively, must notify the Ministry in advance of the plan to cease its activity, indicating, in particular, the economic, financial or technical reasons that impose the cessation. Upon receipt of this notification, the Ministry is entitled to take over ownership of the trademark without charge if the trademark has not been assigned for consideration by the owner or licensee company.

This procedure, in particular, is newly implemented, being applicable as of 2 December 2024.

- Revocation for non-use

The second possibility concerns Trademarks suspected of not being used for at least 5 years. In such case, the Ministry may file before the Italian Patent and Trademark Office an application for revocation for non-use and, if the application is granted, proceed with registering the Trademark in its name.

Trademarks of national interest owned by the Ministry will be announced on its Web site https://www.mimit.gov.it/it/impresa/competitivita-e-nuove-imprese/proprieta-industriale/marchi-di-interesse-storico/elenco-marchi.

As of 27 January 2025, one month after the applicability of the procedures at issue in the list are the following:

- INNOCENTI – Application number 302023000141171

- AUTOBIANCHI – Application number 302023000141189

Free licences for Italian or foreign companies wishing to invest in Italy

The Ministry is authorized to use the Trademarks, licensing them exclusively in favor of companies, including foreign ones, that intend to invest in Italy or transfer production activities located abroad to Italy.

In particular, Italian and foreign companies planning to produce in Italy may apply for a licence to use the above-mentioned Trademarks. The application shall contain specific details regarding the planned investment project, with a focus on the employment impact of the same.

Should the Ministry accept the application, the company will be granted a 10-year free licence, renewable on condition that the company maintains production activities within the national borders.

It is to be noted that, in the event that the company interrupts its activities or relocates its plants outside the Italian territory, the licence contract may be terminated immediately.

What’s next?

The recent regulatory measures are aimed, on the one hand, at keeping alive traditional brands that have been used in Italy for many years and, on the other hand, at allowing Italian and foreign companies to benefit from the incentive of free licences, if they decide to produce in Italy.

It will be interesting to monitor the business developments of these provisions in the coming months, in which the list of Trademarks owned by the Ministry will become longer.

Summary

Artist Mason Rothschild created a collection of digital images named “MetaBirkins”, each of which depicted a unique image of a blurry faux-fur covered the iconic Hermès bags, and sold them via NFT without any (license) agreement with the French Maison. HERMES brought its trademark action against Rothschild on January 14, 2022.

A Manhattan federal jury of nine persons returned after the trial a verdict stating that Mason Rothschild’s sale of the NFT violated the HERMES’ rights and committed trademark infringement, trademark dilution, and cybersquatting (through the use of the domain name “www.metabirkins.com”) because the US First Amendment protection could not apply in this case and awarded HERMES the following damages: 110.000 US$ as net profit earned by Mason Rothschild and 23.000 US$ because of cybersquatting.

The sale of approx. 100 METABIRKIN NFTs occurred after a broad marketing campaign done by Mason Rothschild on social media.

Rothschild’s defense was that digital images linked to NFT “constitute a form of artistic expression” i.e. a work of art protected under the First Amendment and similar to Andy Wahrhol’s paintings of Campbell’s soup cans. The aim of the defense was to have the “Rogers” legal test (so-called after the case Rogers vs Grimaldi) applied, according to which artists are entitled to use trademarks without permission as long as the work has an artistic value and is not misleading the consumers.

NFTs are digital record (a sort of “digital deed”) of ownership typically recorded in a publicly accessible ledger known as blockchain. Rothschild also commissioned computer engineers to operationalize a “smart contract” for each of the NFTs. A smart contract refers to a computer code that is also stored in the blockchain and that determines the name of each of the NFTs, constrains how they can be sold and transferred, and controls which digital files are associated with each of the NFTs.

The smart contract and the NFT can be owned by two unrelated persons or entities, like in the case here, where Rothschild maintained the ownership of the smart contract but sold the NFT.

“Individuals do not purchase NFTs to own a “digital deed” divorced to any other asset: they buy them precisely so that they can exclusively own the content associated with the NFT” (in this case the digital images of the MetaBirkin”), we can read in the Opinion and Order. The relevant consumers did not distinguish the NFTs offered by Rothschild from the underlying MetaBirkin image associated to the NFT.

The question was whether or not there was a genuine artistic expression or rather an unlawful intent to cash in on an exclusive valuable brand name like HERMES.

Mason Rothschild’s appeal to artistic freedom was not considered grounded since it came out that Rothschild was pursuing a commercial rather than an artistic end, further linking himself to other famous brands: Rothschild remarked that “MetaBirkins NFTs might be the next blue chip”. Insisting that he “was sitting on a gold mine” and referring to himself as “marketing king”, Rothschild “also discussed with his associates further potential future digital projects centered on luxury projects such watch NFTs called “MetaPateks” and linked to the famous Swiss luxury watches Patek Philippe.

TAKE AWAY: This is the first US decision on NFT and IP protection for trademarks.

The debate (i) between the protection of the artistic work and the protection of the trademark or other industrial property rights or (ii) between traditional artistic work and subsequent digital reinterpretation by a third party other than the original author, will lead to other decisions (in Italy, we recall the injunction order issued on 20-7-2022 by the Court of Rome in favour of the Juventus football team against the company Blockeras, producer of NFT associated with collectible digital figurines depicting the footballer Bobo Vieri, without Juventus‘ licence or authorisation). This seems to be a similar phenomenon to that which gave rise some 15 years ago to disputes between trademark owners and owners of domain names incorporating those trademarks. For the time being, trademark and IP owners seem to have the upper hand, especially in disputes that seem more commercial than artistic.

For an assessment of the importance and use of NFT and blockchain in association also with IP rights, you can read more here.

Zusammenfassung

Anhand der Geschichte von Nike, die sich aus der Biografie des Gründers Phil Knight ableitet, lassen sich einige Lehren für internationale Vertriebsverträge ziehen: Wie man den Vertrag aushandelt, die Vertragsdauer festlegt, die Exklusivität und die Geschäftsziele definiert und die richtige Art der Streitschlichtung bestimmt.

Worüber ich in diesem Artikel spreche

- Der Streit zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger und die Geburt von Nike

- Wie man eine internationale Vertriebsvereinbarung aushandelt

- Vertragliche Exklusivität in einer Handelsvertriebsvereinbarung

- Mindestumsatzklauseln in Vertriebsverträgen

- Vertragsdauer und Kündigungsfrist

- Eigentum an Marken in Handelsverträgen

- Die Bedeutung der Mediation bei internationalen Handelsverträgen

- Streitbeilegungsklauseln in internationalen Verträgen

- Wie wir Ihnen helfen können

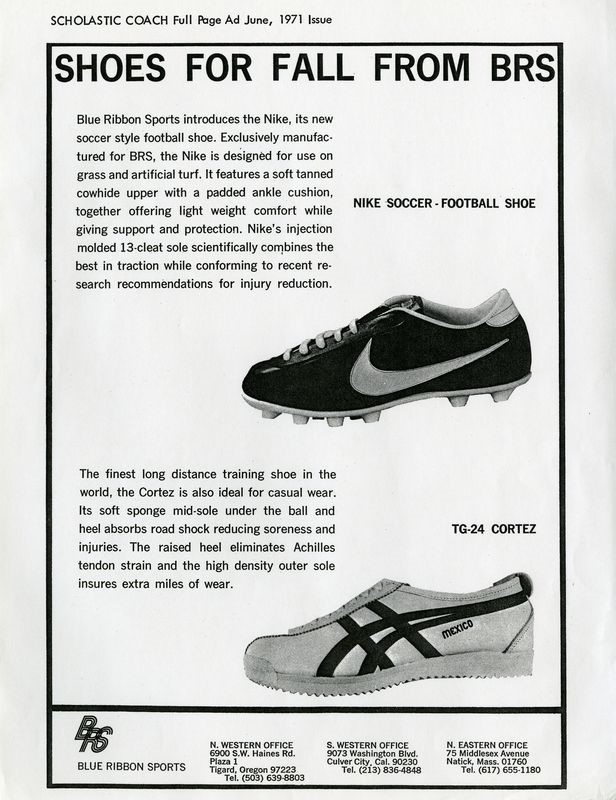

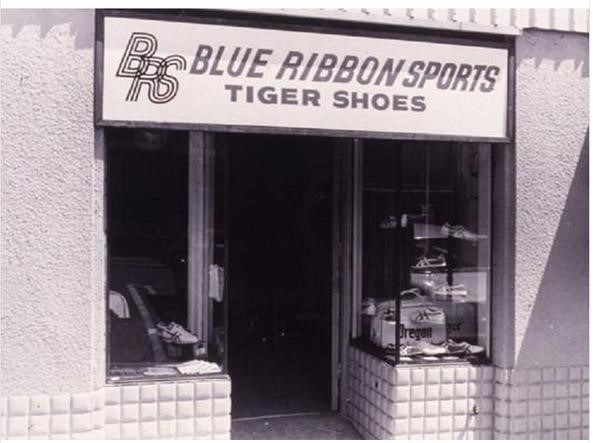

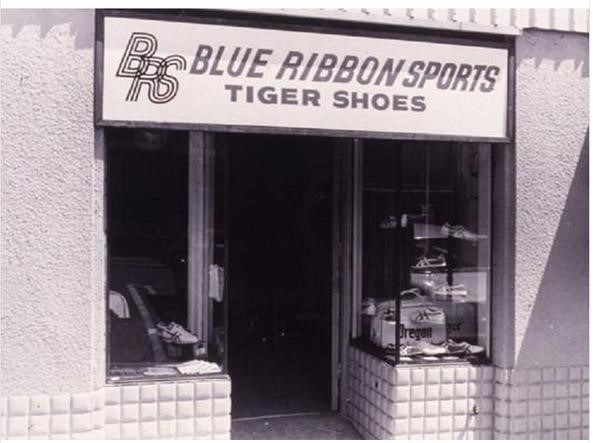

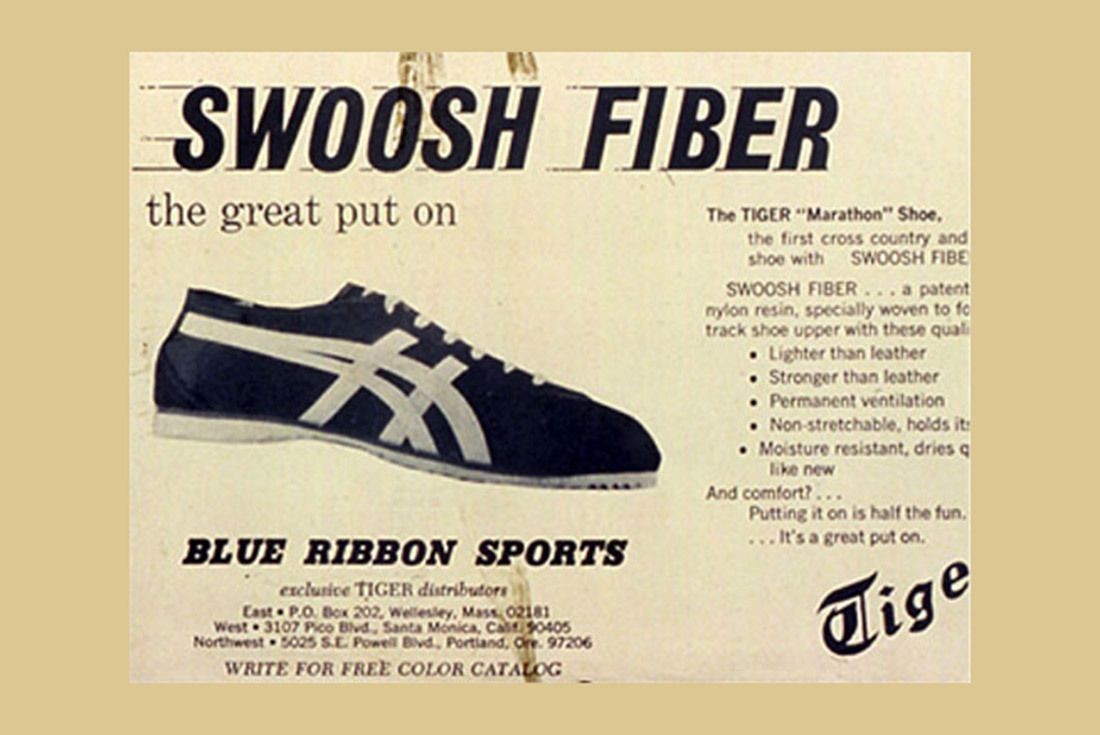

Der Streit zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger und die Geburt von Nike

Warum ist die berühmteste Sportbekleidungsmarke der Welt Nike und nicht Onitsuka Tiger?

Die Biographie des Nike-Schöpfers Phil Knight mit dem Titel “Shoe Dog” gibt hierauf antworten und ist nicht nur für Liebhaber des Genres eine absolut empfehlenswerte Lektüre.

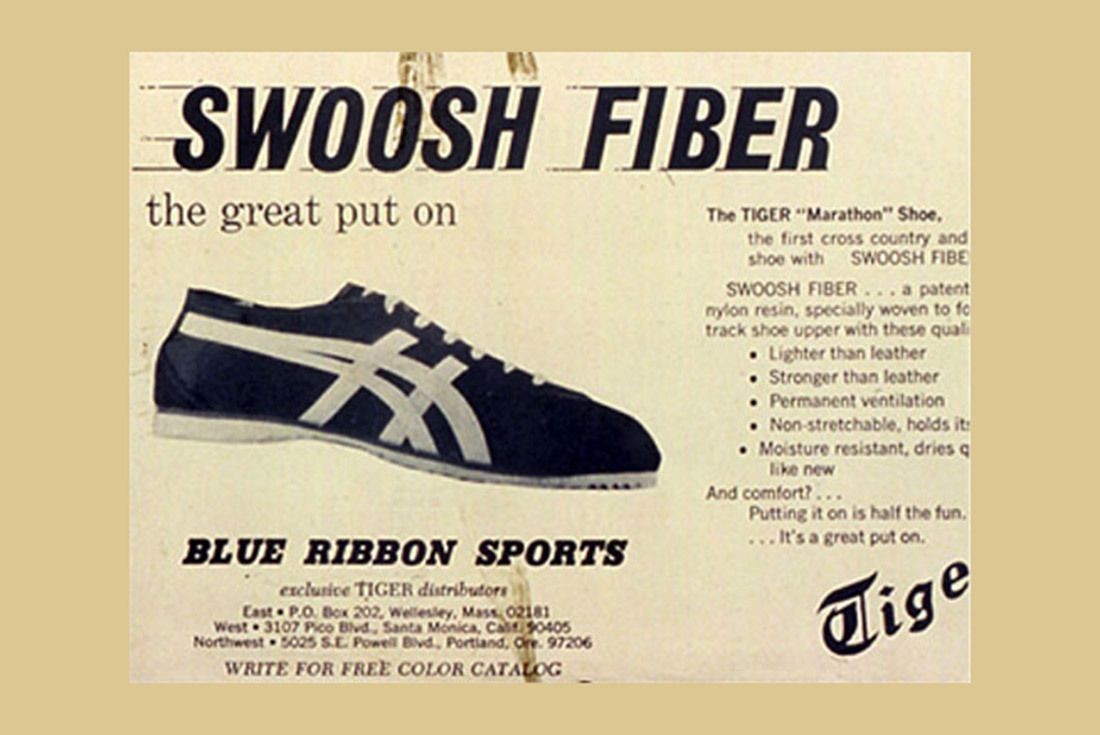

Bewegt von seiner Leidenschaft für den Laufsport und seiner Intuition, dass es auf dem amerikanischen Sportschuhmarkt, der damals von Adidas dominiert wurde, eine Lücke gab, importierte Knight 1964 als erster überhaupt eine japanische Sportschuhmarke, Onitsuka Tiger, in die USA. Mit diesen Sportschuhen konnte sich Knight innerhalb von 6 Jahren einen Marktanteil von satten 70 % sichern.

Das von Knight und seinem ehemaligen College-Trainer Bill Bowerman gegründete Unternehmen hieß damals noch Blue Ribbon Sports.

Die Geschäftsbeziehung zwischen Blue Ribbon-Nike und dem japanischen Hersteller Onitsuka Tiger gestaltete sich trotz der sehr guten Verkaufszahlen und den postiven Wachstumsaussichten von Beginn an als sehr turbulent.

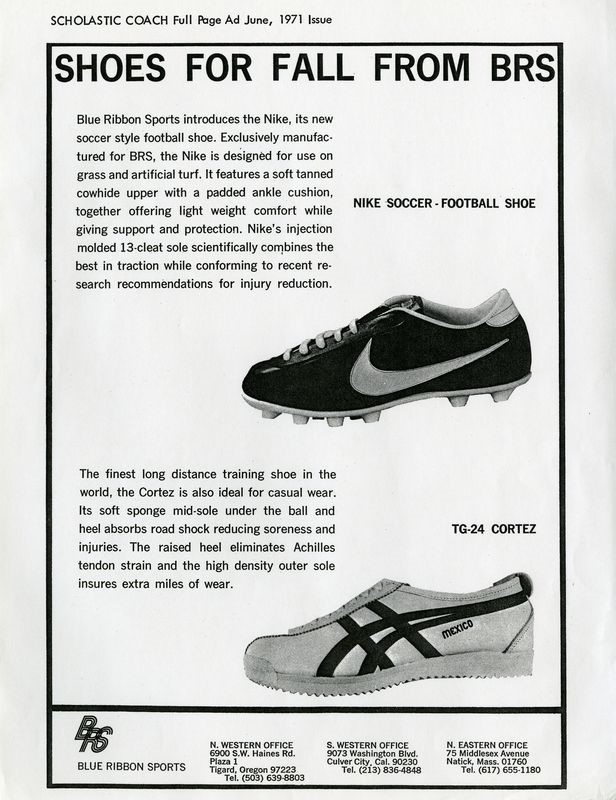

Als Knight dann kurz nach der Vertragsverlängerung mit dem japanischen Hersteller erfuhr, dass Onitsuka in den USA nach einem anderen Vertriebspartner Ausschau hielt , beschloss Knight – aus Angst, vom Markt ausgeschlossen zu werden – sich seinerseits mit einem anderen japanischen Lieferanten zusammenzutun und seine eigene Marke zu gründen. Damit war die spätere Weltmarke Nike geboren.

Als der japanische Hersteller Onitsuka von dem Nike-Projekt erfuhr, verklagte dieser Blue Ribbon wegen Verstoß gegen das Wettbewerbsverbot, welches dem Vertriebshändler die Einfuhr anderer in Japan hergestellter Produkte untersagte, und beendete die Geschäftsbeziehung mit sofortiger Wirkung.

Blue Ribbon führte hiergegen an, dass der Verstoß von dem Hersteller Onitsuka Tiger ausging, der sich bereits als der Vertrag noch in Kraft war und die Geschäfte mehr als gut liefen mit anderen potenziellen Vertriebshändlern getroffen hatte.

Diese Auseinandersetzung führte zu zwei Gerichtsverfahren, eines in Japan und eines in den USA, die der Geschichte von Nike ein vorzeitiges Ende hätten setzen können.

Zum Glück (für Nike) entschied der amerikanische Richter zu Gunsten des Händlers und der Streit wurde mit einem Vergleich beendet: Damit begann für Nike die Reise, die sie 15 Jahre später zur wichtigsten Sportartikelmarke der Welt machen sollte.

Wir werden sehen, was uns die Geschichte von Nike lehrt und welche Fehler bei einem internationalen Vertriebsvertrag tunlichst vermieden werden sollten.

Wie verhandelt man eine internationale Handelsvertriebsvereinbarung?

In seiner Biografie schreibt Knight, dass er bald bedauerte, die Zukunft seines Unternehmens an eine eilig verfasste, wenige Zeilen umfassende Handelsvereinbarung gebunden zu haben, die am Ende einer Sitzung zur Aushandlung der Erneuerung des Vertriebsvertrags geschlossen wurde.

Was beinhaltete diese Vereinbarung?

Die Vereinbarung sah lediglich die Verlängerung des Rechts von Blue Ribbon vor, die Produkte in den USA exklusiv zu vertreiben, und zwar für weitere drei Jahre.

In der Praxis kommt es häufig vor, dass sich internationale Vertriebsverträge auf mündliche Vereinbarungen oder sehr einfache Vertragswerke mit kurzer Dauer beschränken. Die übliche Erklärung dafür ist, dass es auf diese Weise möglich ist, die Geschäftsbeziehung zu testen, ohne die vertragliche Bindung zu eng werden zu lassen.

Diese Art, Geschäfte zu machen, ist jedoch nicht zu empfehlen und kann sogar gefährlich werden: Ein Vertrag sollte niemals als Last oder Zwang angesehen werden, sondern als Garantie für die Rechte beider Parteien. Einen schriftlichen Vertrag nicht oder nur sehr übereilt abzuschließen, bedeutet, grundlegende Elemente der künftigen Beziehung, wie die, die zum Streit zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger führten, ohne klare Vereinbarungen zu belassen: Hierzu gehören Aspekte wie Handelsziele, Investitionen, das Eigentum an Marken – um nur einige zu benennen.

Handelt es sich zudem um einen internationalen Vertrag, ist die Notwendigkeit einer vollständigen und ausgewogenen Vereinbarung noch größer, da in Ermangelung von Vereinbarungen zwischen den Parteien oder in Ergänzung zu diesen Vereinbarungen ein Recht zur Anwendung kommt, mit dem eine der Parteien nicht vertraut ist, d. h. im Allgemeinen das Recht des Landes, in dem der Händler seinen Sitz hat.

Auch wenn Sie sich nicht in einer Blue-Ribbon-Situation befinden, in der es sich um einen Vertrag handelt, von dem die Existenz des Unternehmens abhängt, sollten internationale Verträge stets mit Hilfe eines fachkundigen Anwalts besprochen und ausgehandelt werden, der das auf den Vertrag anwendbare Recht kennt und dem Unternehmer helfen kann, die wichtigen Vertragsklauseln zu ermitteln und auszuhandeln.

Territoriale Exklusivität, kommerzielle Ziele und Mindestumsatzziele

Anlass für den Konflikt zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger war zunächst einmal die Bewertung der Absatzentwicklung auf dem US-Markt.

Onitsuka argumentierte, dass der Umsatz unter dem Potenzial des US-Marktes liege, während nach Angaben von Blue Ribbon die Verkaufsentwicklung sehr positiv sei, da sich der Umsatz bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt jedes Jahr verdoppelt habe und ein bedeutender Anteil des Marktsektors erobert worden sei.

Als Blue Ribbon erfuhr, dass Onituska andere Kandidaten für den Vertrieb seiner Produkte in den USA prüfte, und befürchtete, damit bald vom Markt verdrängt zu werden , bereitete Blue Ribbon die Marke Nike als Plan B vor: Als der japanische Hersteller diese Marke entdeckte , kam es zu einem Rechtsstreit zwischen den Parteien, der zu einem Eklat führte.

Der Streit hätte vielleicht vermieden werden können, wenn sich die Parteien auf kommerzielle Ziele geeinigt hätten und der Vertrag eine in Alleinvertriebsvereinbarungen übliche Klausel enthalten hätte, d.h. ein Mindestabsatzziel für den Vertriebshändler.

In einer Alleinvertriebsvereinbarung gewährt der Hersteller dem Händler einen starken Gebietsschutz für die Investitionen, die der Händler zur Erschließung des zugewiesenen Marktes tätigt.

Um dieses Zugeständnis der Exklusivität auszugleichen, ist es üblich, dass der Hersteller vom Vertriebshändler einen so genannten garantierten Mindestumsatz oder ein Mindestziel verlangt, das der Vertriebshändler jedes Jahr erreichen muss, um den ihm gewährten privilegierten Status zu behalten.

Für den Fall, dass das Mindestziel nicht erreicht wird, sieht der Vertrag dann in der Regel vor, dass der Hersteller das Recht hat, vom Vertrag zurückzutreten (bei einem unbefristeten Vertrag) oder den Vertrag nicht zu verlängern (bei einem befristeten Vertrag) oder aber auch die Gebietsexklusivität aufzuheben bzw. einzuschränken.

Der Vertrag zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger sah derartige Zielvorgaben nicht vor – und das nachdem er gerade erst um drei Jahre verlängert wurde. Hinzukam, dass sich die Parteien bei der Bewertung der Ergebnisse des Vertriebshändlers nicht einig waren. Es stellt sich daher die Frage: Wie können in einem Mehrjahresvertrag Mindestumsatzziele vorgesehen werden?

In Ermangelung zuverlässiger Daten verlassen sich die Parteien häufig auf vorher festgelegte prozentuale Erhöhungsmechanismen: + 10 % im zweiten Jahr, + 30 % im dritten Jahr, + 50 % im vierten Jahr und so weiter.

Das Problem bei diesem Automatismus ist, dass dadurch Zielvorgaben vereinbart werden, die nicht auf tatsächlichen Daten über die künftige Entwicklung der Produktverkäufe, der Verkäufe der Wettbewerber und des Marktes im Allgemeinen basieren , und die daher sehr weit von den aktuellen Absatzmöglichkeiten des Händlers entfernt sein können.

So wäre beispielsweise die Anfechtung des Vertriebsunternehmens wegen Nichterfüllung der Zielvorgaben für das zweite oder dritte Jahr in einer rezessiven Wirtschaft sicherlich eine fragwürdige Entscheidung, die wahrscheinlich zu Meinungsverschiedenheiten führen würde.

Besser wäre eine Klausel, mit der Ziele von Jahr zu Jahr einvernehmlich festgelegt werden. Diese besagt, dass die Ziele zwischen den Parteien unter Berücksichtigung der Umsatzentwicklung in den vorangegangenen Monaten und mit einer gewissen Vorlaufzeit vor Ende des laufenden Jahres vereinbart werden. Für den Fall, dass keine Einigung über die neue Zielvorgabe zustande kommt, kann der Vertrag vorsehen, dass die Zielvorgabe des Vorjahres angewandt wird oder dass die Parteien das Recht haben, den Vertrag unter Einhaltung einer bestimmten Kündigungsfrist zu kündigen.

Andererseits kann die Zielvorgabe auch als Anreiz für den Vertriebshändler dienen: So kann z. B. vorgesehen werden, dass bei Erreichen eines bestimmten Umsatzes die Vereinbarung erneuert, die Gebietsexklusivität verlängert oder ein bestimmter kommerzieller Ausgleich für das folgende Jahr gewährt wird.

Eine letzte Empfehlung ist die korrekte Handhabung der Mindestzielklausel, sofern sie im Vertrag enthalten ist: Es kommt häufig vor, dass der Hersteller die Erreichung des Ziels für ein bestimmtes Jahr bestreitet, nachdem die Jahresziele über einen langen Zeitraum hinweg nicht erreicht oder nicht aktualisiert wurden, ohne dass dies irgendwelche Konsequenzen hatte.

In solchen Fällen ist es möglich, dass der Händler behauptet, dass ein impliziter Verzicht auf diesen vertraglichen Schutz vorliegt und der Widerruf daher nicht gültig ist: Um Streitigkeiten zu diesem Thema zu vermeiden, ist es ratsam, in der Mindestzielklausel ausdrücklich vorzusehen, dass die unterbliebene Anfechtung des Nichterreichens des Ziels während eines bestimmten Zeitraums nicht bedeutet, dass auf das Recht, die Klausel in Zukunft zu aktivieren, verzichtet wird.

Die Kündigungsfrist für die Beendigung eines internationalen Vertriebsvertrags

Der andere Streitpunkt zwischen den Parteien war die Verletzung eines Wettbewerbsverbots: Blue Ribbon verkaufte die Marke Nike , obwohl der Vertrag den Verkauf anderer in Japan hergestellter Schuhe untersagte.

Onitsuka Tiger behauptete, Blue Ribbon habe gegen das Wettbewerbsverbot verstoßen, während der Händler die Ansicht vertrat , dass er angesichts der bevorstehenden Entscheidung des Herstellers, die Vereinbarung zu kündigen, keine andere Wahl hatte.

Diese Art von Streitigkeiten kann vermieden werden, indem für die Beendigung (oder Nichtverlängerung) eine klare Kündigungsfrist festgelegt wird: Diese Frist hat die grundlegende Funktion, den Parteien die Möglichkeit zu geben, sich auf die Beendigung der Beziehung vorzubereiten und ihre Aktivitäten nach der Beendigung neu zu organisieren.

Um insbesondere Streitigkeiten wie die zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger zu vermeiden, kann in einem internationalen Vertriebsvertrag vorgesehen werden, dass die Parteien während der Kündigungsfristmit anderen potenziellen Vertriebshändlern und Herstellern in Kontakt treten können und dass dies nicht gegen die Ausschließlichkeits- und Wettbewerbsverpflichtungen verstößt.

Im Fall von Blue Ribbon war der Händler über die bloße Suche nach einem anderen Lieferanten hinaus sogar noch einen Schritt weiter gegangen, da er begonnen hatte, Nike-Produkte zu verkaufen, während der Vertrag mit Onitsuka noch gültig war. Dieses Verhalten stellt einen schweren Verstoß gegen die getroffene Ausschließlichkeitsvereinbarung dar.

Ein besonderer Aspekt, der bei der Kündigungsfrist zu berücksichtigen ist, ist die Dauer: Wie lang muss die Kündigungsfrist sein, um als fair zu gelten? Bei langjährigen Geschäftsbeziehungen ist es wichtig, der anderen Partei genügend Zeit einzuräumen, um sich auf dem Markt neu zu positionieren, nach alternativen Vertriebshändlern oder Lieferanten zu suchen oder (wie im Fall von Blue Ribbon/Nike) eine eigene Marke zu schaffen und einzuführen.

Ein weiteres Element, das bei der Mitteilung der Kündigung zu berücksichtigen ist, besteht darin, dass die Kündigungsfrist so bemessen sein muss, dass der Vertriebshändler die zur Erfüllung seiner Verpflichtungen während der Vertragslaufzeit getätigten Investitionen amortisieren kann; im Fall von Blue Ribbon hatte der Vertriebshändler auf ausdrücklichen Wunsch des Herstellers eine Reihe von Einmarkengeschäften sowohl an der West- als auch an der Ostküste der USA eröffnet.

Eine Kündigung des Vertrags kurz nach seiner Verlängerung und mit einer zu kurzen Vorankündigung hätte es dem Vertriebshändler nicht erlaubt, das Vertriebsnetz mit einem Ersatzprodukt neu zu organisieren, was die Schließung der Geschäfte, die die japanischen Schuhe bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt verkauft hatten, erzwungen hätte.

Im Allgemeinen ist es ratsam, eine Kündigungsfrist von mindestens 6 Monaten vorzusehen. Bei internationalen Vertriebsverträgen sollten jedoch neben den von den Parteien getätigten Investitionen auch etwaige spezifische Bestimmungen des auf den Vertrag anwendbaren Rechts (hier z. B. eine eingehende Analyse der plötzlichen Kündigung von Verträgen in Frankreich) oder die Rechtsprechung zum Thema Rücktritt von Geschäftsbeziehungen beachtet werden (in einigen Fällen kann die für einen langfristigen Vertriebskonzessionsvertrag als angemessen erachtete Frist 24 Monate betragen).

Schließlich ist es normal, dass der Händler zum Zeitpunkt des Vertragsabschlusses noch im Besitz von Produktvorräten ist: Dies kann problematisch sein, da der Händler in der Regel die Vorräte auflösen möchte (Blitzverkäufe oder Verkäufe über Internetkanäle mit starken Rabatten), was der Geschäftspolitik des Herstellers und der neuen Händler zuwiderlaufen kann.

Um diese Art von Situation zu vermeiden, kann in den Vertriebsvertrag eine Klausel aufgenommen werden, die das Recht des Herstellers auf Rückkauf der vorhandenen Bestände bei Vertragsende regelt, wobei der Rückkaufpreis bereits festgelegt ist (z. B. in Höhe des Verkaufspreises an den Händler für Produkte der laufenden Saison, mit einem Abschlag von 30 % für Produkte der vorangegangenen Saison und mit einem höheren Abschlag für Produkte, die mehr als 24 Monate zuvor verkauft wurden).

Markeninhaberschaft in einer internationalen Vertriebsvereinbarung

Im Laufe der Vertriebsbeziehung hatte Blue Ribbon eine neuartige Sohle für Laufschuhe entwickelt und die Marken Cortez und Boston für die Spitzenmodelle der Kollektion geprägt, die beim Publikum sehr erfolgreich waren und große Popularität erlangten: Bei Vertragsende beanspruchten nun beide Parteien das Eigentum an den Marken.

Derartige Situationen treten häufig in internationalen Vertriebsbeziehungen auf: Der Händler lässt die Marke des Herstellers in dem Land, in dem er tätig ist, registrieren, um Konkurrenten daran zu hindern, dies zu tun, und um die Marke im Falle des Verkaufs gefälschter Produkte schützen zu können; oder es kommt vor, dass der Händler, wie in dem hier behandelten Streitfall, an der Schaffung neuer, für seinen Markt bestimmter Marken mitwirkt.

Am Ende der Geschäftsbeeziehung, wenn keine klare Vereinbarung zwischen den Parteien vorliegt, kann es zu einem Streit wie im Fall Nike kommen: Wer ist der Eigentümer der Marke – der Hersteller oder der Händler?

Um Missverständnisse zu vermeiden, ist es ratsam, die Marke in allen Ländern zu registrieren, in denen die Produkte vertrieben werden, und nicht nur dort: Im Falle Chinas zum Beispiel ist es ratsam, die Marke auch dann zu registrieren, wenn sie dort nicht vertreiben wird, um zu verhindern, dass Dritte die Marke in böser Absicht übernehmen (weitere Informationen finden Sie in diesem Beitrag auf Legalmondo).

Es ist auch ratsam, in den Vertriebsvertrag eine Klausel aufzunehmen, die dem Händler die Eintragung der Marke (oder ähnlicher Marken) in dem Land, in dem er tätig ist, untersagt und dem Hersteller ausdrücklich das Recht einräumt, die Übertragung der Marke zu verlangen, falls dies dennoch geschieht.

Eine solche Klausel hätte die Entstehung des Rechtsstreits zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger verhindert.

Der von uns geschilderte Sachverhalt stammt aus dem Jahr 1976: Heutzutage ist es ratsam, im Vertrag nicht nur die Eigentumsverhältnisse an der Marke und die Art und Weise der Nutzung durch den Händler und sein Vertriebsnetz zu klären, sondern auch die Nutzung der Marke wie auch der Unterscheidungszeichen des Herstellers in den Kommunikationskanälen, insbesondere in den sozialen Medien, zu regeln.

Es ist ratsam, eindeutig festzulegen, dass niemand anderes als der Hersteller Eigentümer der Social-Media-Profile wie auch der erstellten Inhalte und der Daten ist, die durch die Verkaufs-, Marketing- und Kommunikationsaktivitäten in dem Land, in dem der Händler tätig ist, generiert werden, und dass er nur die Lizenz hat, diese gemäß den Anweisungen des Eigentümers zu nutzen.

Darüber hinaus ist es sinnvoll, in der Vereinbarung festzulegen, wie die Marke verwendet wird und welche Kommunikations- und Verkaufsförderungsmaßnahmen auf dem Markt ergriffen werden, um Initiativen zu vermeiden, die negative oder kontraproduktive Auswirkungen haben könnten.

Die Klausel kann auch durch die Festlegung von Vertragsstrafen für den Fall verstärkt werden, dass sich der Händler bei Vertragsende weigert, die Kontrolle über die digitalen Kanäle und die im Rahmen der Geschäftstätigkeit erzeugten Daten zu übertragen.

Mediation in internationalen Handelsverträgen

Ein weiterer interessanter Punkt, der sich am Fall Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger erläutern lässt , steht im Zusammenhang mit der Bewältigung von Konflikten in internationalen Vertriebsbeziehungen: Situationen wie die, die wir gesehen haben, können durch den Einsatz von Mediation effektiv gelöst werden.

Dabei handelt es sich um einen Schlichtungsversuch, mit dem ein spezialisiertes Gremium oder ein Mediator betraut wird, um eine gütliche Einigung zu erzielen und ein Gerichtsverfahren zu vermeiden.

Die Mediation kann im Vertrag als erster Schritt vor einem eventuellen Gerichts- oder Schiedsverfahren vorgesehen sein oder sie kann freiwillig im Rahmen eines bereits laufenden Gerichts- oder Schiedsverfahrens eingeleitet werden.

Die Vorteile sind vielfältig: Der wichtigste ist die Möglichkeit, eine wirtschaftliche Lösung zu finden, die die Fortsetzung der Beziehung ermöglicht, anstatt nur nach Wegen zur Beendigung der Geschäftsbeziehung zwischen den Parteien zu suchen.

Ein weiterer interessanter Aspekt der Mediation ist die Überwindung von persönlichen Konflikten: Im Fall Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka zum Beispiel war ein entscheidendes Element für die Eskalation der Probleme zwischen den Parteien die schwierige persönliche Beziehung zwischen dem CEO von Blue Ribbon und dem Exportmanager des japanischen Herstellers, die durch starke kulturelle Unterschiede verschärft wurde.

Der Mediationsprozess führt eine dritte Person ein, die in der Lage ist, einen Dialog mit den Parteien zu führen und sie bei der Suche nach Lösungen von gegenseitigem Interesse zu unterstützen, was entscheidend sein kann, um Kommunikationsprobleme oder persönliche Feindseligkeiten zu überwinden.

Für alle, die sich für dieses Thema interessieren, verweisen wir auf den hierzu verfassten Beitrag auf Legalmondo sowie auf die Aufzeichnung eines kürzlich durchgeführten Webinars zur Mediation internationaler Konflikte.

Streitbeilegungsklauseln in internationalen Vertriebsvereinbarungen

Der Streit zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger führte dazu, dass die Parteien zwei parallele Gerichtsverfahren einleiteten, eines in den USA (durch den Händler) und eines in Japan (durch den Hersteller).

Dies war nur deshalb möglich, weil der Vertrag nicht ausdrücklich vorsah, wie etwaige künftige Streitigkeiten beigelegt werden sollten. In der Konsequenz führte dies zu einer prozessual sehr komplizierten Situation mit gleich zwei gerichtlichen Fronten in verschiedenen Ländern.

Die Klauseln, die festlegen, welches Recht auf einen Vertrag anwendbar ist und wie Streitigkeiten beigelegt werden, werden in der Praxis als „Mitternachtsklauseln“ bezeichnet, da sie oft die letzten Klauseln im Vertrag sind, die spät in der Nacht ausgehandelt werden.

Es handelt sich hierbei um sehr wichtige Klauseln, die bewusst gewählt werden müssen, um unwirksame oder kontraproduktive Lösungen zu vermeiden.

Wie wir Ihnen helfen können

Der Abschluss eines internationalen Handelsvertriebsvertrags ist eine wichtige Investition, denn er regelt die vertragliche Beziehungen zwischen den Parteien verbindlich für die Zukunft und gibt ihnen die Instrumente an die Hand, um alle Situationen zu bewältigen, die sich aus der künftigen Zusammenarbeit ergeben werden.

Es ist nicht nur wichtig, eine korrekte, vollständige und ausgewogene Vereinbarung auszuhandeln und abzuschließen, sondern auch zu wissen, wie sie im Laufe der Jahre zu handhaben ist, vor allem, wenn Konfliktsituationen auftreten.

Legalmondo bietet Ihnen die Möglichkeit, mit Anwälten zusammenzuarbeiten, die in mehr als 60 Ländern Erfahrung im internationalen Handelsvertrieb haben: Bei bestehendem Beratungsbedarf schreiben Sie uns.

In this internet age, the limitless possibilities of reaching customers across the globe to sell goods and services comes the challenge of protecting one’s Intellectual Property Right (IPR). Talking specifically of trademarks, like most other forms of IPR, the registration of a trademark is territorial in nature. One would need a separate trademark filing in India if one intends to protect the trademark in India.

But what type of trademarks are allowed registration in India and what is the procedure and what are the conditions?

The Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (the Registry) is the government body responsible for the administration of trademarks in India. When seeking trademark registration, you will need an address for service in India and a local agent or attorney. The application can be filed online or by paper at the Registry. Based on the originality and uniqueness of the trademark, and subject to opposition or infringement claims by third parties, the registration takes around 18-24 months or even more.

Criteria for adopting and filing a trademark in India

To be granted registration, the trademark should be:

- non-generic

- non-descriptive

- not-identical

- non–deceptive

Trademark Search

It is not mandatory to carry out a trademark search before filing an application. However, the search is recommended so as to unearth conflicting trademarks on file.

How to make the application?

One can consider making a trademark application in the following ways:

- a fresh trademark application through a local agent or attorney;

- application under the Paris Convention: India being a signatory to the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, a convention application can be filed by claiming priority of a previously filed international application. For claiming such priority, the applicant must file a certified copy of the priority document, i.e., the earlier filed international application that forms the basis of claim for priority in India;

- application through the Madrid Protocol: India acceded to the Madrid Protocol in 2013 and it is possible to designate India in an international application.

Objection by the Office – Grounds of Refusal

Within 2-4 months from the date of filing of the trademark application (4-6 months in the case of Madrid Protocol applications), the Registry conducts an examination and sometimes issues an office action/examination report raising objections. The applicant must respond to the Registry within one month. If the applicant fails to respond, the trademark application will be deemed abandoned.

A trademark registration in India can be refused by the Registry for absolute grounds such as (i) the trademark being devoid of any distinctive character (ii) trademark consists of marks that designate the kind, quality, quantity values, geographic origins or time or production of the goods or services (iii) the trademark causes confusion or deceives public. A relative ground for refusal is generally when a trademark is similar or deceptively similar to an earlier trademark.

Objection Hearing

When the Registry is not satisfied with the response, a hearing is scheduled within 8-12 months. During the hearing, the Registry either accepts or rejects the registration.

Publication in TM journal

After acceptance for registration, the trademark will be published in the Trade Marks Journal.

Third Party Opposition

Any person can oppose the trademark within four months of the date of publication in the journal. If there is no opposition within 4-months, the mark would be granted protection by the Registry. An opposition would lead to prosecution proceedings that take around 12-18 months for completion.

Validity of Trademark Registration

The registration dates back to the date of the application and is renewable every 10 years.

“Use of Mark” an important condition for trademark registration

- “First to Use” Rule over “First-to-File” Rule: An application in India can be filed on an “intent to use” basis or by claiming “prior use” of the trademark in India. Unlike other jurisdictions, India follows “first to use” rule over the “first-to-file” rule. This means that the first person who can prove significant use of a trade mark in India will generally have superior rights over a person who files a trade mark application prior but with a later user date or acquires registration prior but with a later user date.

- Spill-over Reputation considered as Use: Given the territorial protection granted for trademarks, the Indian Trademark Law protects the spill-over reputation of overseas trademark even where the trademark has not been used and/or registered in India. This is possible because knowledge of the trademark in India and the reputation acquired through advertisements on television, Internet and publications can be considered as valid proof of use.

Descriptive Marks to acquire distinctiveness to be eligible for registration

Unlike in the US, Indian trademark law does not generally permit registration of a descriptive trademark. A descriptive trademark is a word that identifies the characteristics of the product or service to which the trademark pertains. It is similar to an adjective. An example of descriptive marks is KOLD AND KREAMY for ice cream and CHOCO TREAT in respect of chocolates. However, several courts in India have interpreted that descriptive trademark can be afforded registration if due to its prolonged use in trade it has lost its primary descriptive meaning and has become distinctive in relation to the goods it deals with. Descriptive marks always have to be supported with evidence (preferably from before the date of application for registration) to show that the trademark has acquired a distinctive character as a result of the use made of it or that it was a well-known trademark.

Acquired distinctiveness a criterion for trademark protection

Even if a trademark lacks inherent distinctiveness, it can still be registered if it has acquired distinctiveness through continuous and extensive use. All one has to prove is that before the date of application for registration:

- the trademark has acquired a distinctive character as a result of use;

- established a strong reputation and goodwill in the market; and

- the consumers relate only to the trademark for the respective product or services due to its continuous use.

How can one stop someone from misusing or copying the trademark in India?

An action of passing off or infringement can be taken against someone copying or misusing a trademark.

For unregistered trademarks, a common law action of passing off can be initiated. The passing off of trademarks is a tort actionable under common law and is mainly used to protect the goodwill attached to unregistered trademarks. The owner of the unregistered trademark has to establish its trademark rights by substantiating the trademark’s prior use in India or trans-border reputation in India and prove that the two marks are either identical or similar and there is likelihood of confusion.

For Registered trademarks, a statutory action of infringement can be initiated. The registered proprietor only needs to prove the similarity between the marks and the likelihood of confusion is presumed.

In both the cases, a court may grant relief of injunction and /or monetary compensation for damages for loss of business and /or confiscation or destruction of infringing labels etc. Although registration of trademark is prima facie evidence of validity, registration cannot upstage a prior consistent user of trademark for the rule is ‘priority in adoption prevails over priority in registration’.

Appeals

Any decision of the Registrar of Trademarks can be appealed before the high courts within three months of the Registrar’s order.

It’s thus preferable to have a strategy for protecting trademarks before entering the Indian market. This includes advertising in publications and online media that have circulation and accessibility in India, collating all relevant records evidencing the first use of the mark in India, taking offensive action against the infringing local entity, or considering negotiations depending upon the strength of the foreign mark and the transborder reputation it carries.

Summary – The company that incurs into a counterfeiting of its Community design shall not start as many disputes as are the countries where the infringement has been carried out: it will be sufficient to start a lawsuit in just one court of the Union, in its capacity as Community design court, and get a judgement against a counterfeiter enforceable in different, or even all, Countries of the European Union.

Italian companies are famous all over the world thanks to their creative abilities regarding both industrial inventions and design: in fact, they often make important economic investments in order to develop innovative solutions for the products released on the market.

Such investments, however, must be effectively protected against cases of counterfeiting that, unfortunately, are widely spread and ever more realizable thanks to the new technologies such as the e-commerce. Companies must be very careful in protecting their own products, at least in the whole territory of the European Union, since counterfeiting inevitably undermines the efforts made for the research of an original product.

In this respect the content of a recent judgement issued by the Court of Milan, section specialized in business matters, No. 2420/2020, appears very significant since it shows that it is possible and necessary, in case of counterfeiting (in this case the matter is the counterfeiting of a Community design) to promptly take a legal action, that is to start a lawsuit to the competent Court specialized in business matters.

The Court, by virtue of the EU Regulation No. 6/2002, will issue an order (an urgent and protective remedy ante causam or a judgement at the end of the case) effective in the whole European territory so preventing any extra UE counterfeiter from marketing, promoting and advertising a counterfeited product.

The Court of Milan, in this specific case, had to solve a dispute aroused between an Italian company producing a digital flowmeter, being the subject of a Community registration, and a competitor based in Hong Kong. The Italian company alleged that the latter had put on the European market some flow meters in infringement of a Community design held by the first.

First of all, the panel of judges effected a comparison between the Community design held by the Italian company (plaintiff) and the flow meter manufactured and distributed by the Hong Kong company (defendant). The judges noticed that the latter actually coincided both for dimensions and proportions with the first so that even an expert in the field (the so-called informed user) could mistake the product of the defendant company with that of the plaintiff company owner of the Community design.

The Court of Milan, in its capacity as Community designs court, after ascertaining the counterfeiting, in the whole European territory, carried out by the defendant at the expense of the plaintiff, with judgement No. 2420/2020 prohibited, by virtue of articles 82, 83 and 89 of the EU Regulation No. 6/2002, the Hong Kong company to publicize, offer for sale, import and market, by any means and methods, throughout the European Union, even through third parties, the flow meter subject to the present judgement, with any name if presenting similar characteristics.

The importance of this judgement lies in its effects spread all over the territory of the European Union. This is not a small thing since the company that incurs into a counterfeiting of its Community design shall not start as many disputes as are the countries where the infringement has been carried out: it will be sufficient for this company to start a lawsuit in just one court of the Union, in its capacity as Community design court, and get a judgement against a counterfactor who makes an illicit in different, or even all, Countries of the European Union.

Said judgement will be even more effective if we consider that, by virtue of the UE Customs Regulation No. 608/2013, the company will be able to communicate the existence of a counterfeited product to the customs of the whole European territory (through a single request filed with the customs with the territorial jurisdiction) in order to have said products blocked and, in case, destroyed.

Summary – What can the owner (or licensee) of a trademark do if an unauthorized third party resells products with its trademark on an online platform? This issue was addressed in the judgment of C-567/18 of 2 April 2020, in which the Court of Justice of the European Union confirmed that platforms (Amazon Marketplace, in this case) storing goods which infringe trademark rights are not liable for such infringement, unless the platform puts them on the market or is aware of the infringement. Conversely, platforms (such as Amazon Retail) that contribute to the distribution or resell the products themselves may be liable.

Background

Coty – a German company, distributor of perfumes, holding a licence for the EU trademark “Davidoff” – noted that third-party sellers were offering on Amazon Marketplace perfumes bearing the „Davidoff Hot Water“ brand, which had been put in the EU market without its consent.

After reaching an agreement with one of the sellers, Coty sued Amazon in order to prevent it from storing and shipping those perfumes unless they were placed on the EU market with Coty’s consent. Both the Court of First Instance and the Court of Appeal rejected Coty’s request, which brought an appeal before the German Court of Cassation, which in turn referred the matter to the Court of Justice of the EU.

What is the Exhaustion of the rights conferred by a trademark

The principle of exhaustion is envisaged by EU law, according to which, once a good is put on the EU market, the proprietor of the trademark right on that specific good can no longer limit its use by third parties.

This principle is effective only if the entry of the good (the reference is to the individual product) on the market is done directly by the right holder, or with its consent (e.g. through an operator holding a licence).

On the contrary, if the goods are placed on the market by third parties without the consent of the proprietor, the latter may – by exercising the trademark rights established by art. 9, par. 3 of EU Regulation 2017/1001 – prohibit the use of the trademark for the marketing of the products.

By the legal proceedings which ended before the Court of Justice of the EU, Coty sought to enforce that right also against Amazon, considering it to be a user of the trademark, and therefore liable for its infringement.

What is the role of Amazon?

The solution of the case revolves around the role of the web platform.

Although Amazon provides users with a unique search engine, it hosts two radically different sales channels. Through the Amazon Retail channel, the customer buys products directly from the Amazon company, which operates as a reseller of products previously purchased from third party suppliers.

The Amazon Marketplace, on the other hand, displays products owned by third-party vendors, so purchase agreements are concluded between the end customer and the vendor. Amazon gets a commission on these transactions, while the vendor assumes the responsibility for the sale and can manage the prices of the products independently.

According to the German courts which rejected Coty’s claims in the first and second instance, Amazon Marketplace essentially acts as a depository, without offering the goods for sale or putting them on the market.

Coty, vice versa, argues that Amazon Marketplace, by offering various marketing-services (including: communication with potential customers in order to sell the products; provision of the platform through which customers conclude the contract; and consistent promotion of the products, both on its website and through advertisements on Google), can be considered as a „user“ of the trademark, within the meaning of Article 9, paragraph 3 of EU Regulation 2017/1001.

The decision of the Court of Justice of the European Union

Advocate General Campos Sanchez-Bordona, in the opinion delivered on 28 November 2019, had suggested to the Court to distinguish between: the mere depositaries of the goods, not to be considered as „users“ of the trademark for the purposes of EU Regulation 2017/1001; and those who – in addition to providing the deposit service – actively participate in the distribution of the goods. These latter, in the light of art. 9, par. 3, letter b) of EU Regulation 2017/1001, should be considered as „users“ of the trademark, and therefore directly responsible in case of infringements.

The Bundesgerichtshof (Federal Court of Justice of Germany), however, had already partially answered the question when it referred the matter to the European Court, stating that Amazon Marketplace “merely stored the goods concerned, without offering them for sale or putting them on the market”, both operations carried out solely by the vendor.

The EU Court of Justice ruled the case on the basis of some precedents, in which it had already stated that:

- The expression “using” involves at the very least, the use of the sign in the commercial communication. A person may thus allow its clients to use signs which are identical or similar to trademarks without itself using those signs (see Google vs Louis Vuitton, Joined Cases C-236/08 to C-238/08, par. 56).

- With regard to e-commerce platforms, the use of the sign identical or similar to a trademark is made by the sellers, and not by the platform operator (see L’Oréal vs eBay, C‑324/09, par. 103).

- The service provider who simply performs a technical part of the production process cannot be qualified as a „user“ of any signs on the final products. (see Frisdranken vs Red Bull, C‑119/10, par. 30. Frisdranken is an undertaking whose main activity is filling cans, supplied by a third party, already bearing signs similar to Redbull’s registered trademarks).

On the basis of that case-law and the qualification of Amazon Marketplace provided by the referring court, the European Court has ruled that a company which, on behalf of a third party, stores goods which infringe trademark rights, if it is not aware of that infringement and does not offer them for sale or place them on the market, is not making “use” of the trademark and, therefore, is not liable to the proprietor of the rights to that trademark.

Conclusion

After Coty had previously been the subject of a historic ruling on the matter (C-230/16 – link to the Legalmondo previous post), in this case the Court of Justice decision confirmed the status quo, but left the door open for change in the near future.

A few considerations on the judgement, before some practical tips:

- The Court did not define in positive terms the criteria for assessing whether an online platform performs sufficient activity to be considered as a user of the sign (and therefore liable for any infringement of the registered trademark). This choice is probably dictated by the fact that the criteria laid down could have been applied (including to the various companies belonging to the Amazon group) in a non-homogeneous manner by the various Member States’ national courts, thus jeopardising the uniform application of European law.

- If the Court of Justice had decided the case the other way around, the ruling would have had a disruptive impact not only on Amazon’s Marketplace, but on all online operators, because it would have made them directly responsible for infringements of IP rights by third parties.

- If the perfumes in question had been sold through Amazon Retail, there would have been no doubt about Amazon’s responsibility: through this channel, sales are concluded directly between Amazon and the end customer.

- The Court has not considered whether: (i) Amazon could be held indirectly liable within the meaning of Article 14(1) of EU Directive 2000/31, as a “host” which – although aware of the illegal activity – did not prevent it; (ii) under Article 11 of EU Directive 2004/48, Coty could have acted against Amazon as an intermediary whose services are used by third parties to infringe its IP right. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that Amazon may be held (indirectly) liable for the infringements committed, including on the Marketplace: this aspect will have to be examined in detail on a case-by-case basis.

Practical tips

What can the owner (or licensee) of a trademark do if an unauthorized third party resells products with its trademark on an online platform?

- Gather as much evidence as possible of the infringement in progress: the proof of the infringement is one of the most problematic aspects of IP litigation.

- Contact a specialized lawyer to send a cease-and-desist letter to the unauthorized seller, ordering the removal of the products from the platform and asking the compensation for damages suffered.

- If the products are not removed from the marketplace, the trademark owner might take legal action to obtain the removal of the products and compensation for damages.

- In light of the judgment in question, the online platforms not playing an active role in the resale of goods remain not directly responsible for IP violations. Nevertheless, it is suggested to consider sending the cease-and-desist letter to them as well, in order to put more pressure on the unauthorised seller.

- The sending of the cease-and-desist letter also to the platform – especially in the event of several infringements – may also be useful to demonstrate its (indirect) liability for lack of vigilance, as seen in point 4) of the above list.

Quick summary – Poland has recently introduced tax incentives which aim at promoting innovations and technology. The new support instrument for investors conducting R&D activity is named «IP Box» and allows for a preferential taxation of qualified profits made on commercialization of several types of qualified property rights. The preferential income tax rate amounts to 5%. By contrast, the general rate is in most cases 19%.

The Qualified Intellectual Property Rights

The intellectual property rights which may be the source of the qualified profit subject the preferential taxation are the following:

- rights to an invention (patents)

- additional protective rights for an invention

- rights for the utility model

- rights from the registration of an industrial design

- rights from registration of the integrated circuit topography

- additional protection rights for a patent for medicinal product or plant protection product

- rights from registration of medicinal or veterinary product

- rights from registration of new plant varieties and animal breeds, and

- rights to a computer program

The above catalogue of qualified intellectual property rights is exhaustive.

Conditions for the application of the Patent Box

A taxpayer may apply the preferential 5% rate on the condition that he or she has created, developed or improved these rights in the course of his/her R&D activities. A taxpayer may create intellectual property but it may also purchase or license it on the exclusive basis, provided that the taxpayer then incurs costs related to the development or improvement of the acquired right.

For example an IT company may create a computer program itself within its R&D activity or it may acquire it from a third party and develop it further. Future income received as a result of commercialization of this computer program may be subject to the tax relief.

The following kinds of income may be subject to tax relief:

- fees or charges arising from the license for qualified intellectual property rights

- the sale of qualified intellectual property rights

- qualified intellectual property rights included in the sale price of the products or services

- the compensation for infringement of qualified intellectual property rights if obtained in litigation proceedings, including court proceedings or arbitration.

How to calculate the tax base

The preferential tax rate is 5% on the tax base. The latter is calculated according to a special formula: the total income received from a particular IP is reduced by a significant part of expenditures on the R&D activities as well as on the creation, acquisition and development of this IP. The appropriate factor, named «nexus», is applied to calculate the tax base.

The tax relief is applicable at the end of the calendar year. This means that during the year the income tax advance payments are due according to the regular rate. Consequently in many instances the taxpayer will recover a part of the tax already paid during the previous calendar year.

It is advisable that the taxpayer applies for the individual tax ruling to the competent authority in order to receive a binding confirmation that its particular IP is eligible for the tax reduction.

It is also crucial that the taxpayer keeps the detailed accounting records of all R&D activities as well as the income and the expenses related to each R&D project (including employment costs). The records should reflect the link of incurred R&D costs with the income from intellectual property rights.

Obligations related to the application of the tax relief

In particular such a taxpayer is obliged to keep records which allow for monitoring and tracking the effects of research and development works. If, based on the accounting records kept by a taxpayer, it is not possible to determine the income (loss) from qualified intellectual property rights, the taxpayer will be obliged to pay the tax based on general rules.

The tax relief may be applied throughout the duration of the legal protection of eligible intellectual property rights.In case if a given IP is subject to notification or registration procedure (the expectative of obtaining a qualified intellectual property right), a taxpayer may benefit from tax relief from the moment of filing or submitting an application for registration. In case of withdrawal of the application, refusal of registration or rejection of the application , the amount of relief will have to be returned.

The above tax relief combined with a governmental programme of grant aid for R&D projects make Polish research, development and innovation environment more and more beneficial for investors.

Startups and Trademarks – Get it right from the Start

As a lawyer, I have been privileged to work closely with entrepreneurs of all backgrounds and ages (not just young people, a common stereotype on this field) and startups, providing legal advice on a wide range of areas.

Helping them build their businesses, I have identified a few recurrent mistakes, most of them arising mainly from the lack of experience on dealing with legal issues, and some others arising from the lack of understanding on the value added by legal advice, especially when we are referring to Intellectual Property (IP).

Both of them are understandable, we all know that startups (specially on an early stage of development) deal with the lack of financial resources and that the founders are pretty much focused on what they do best, which is to develop their own business model and structure, a new and innovative business.

Nevertheless it is important to stress that during this creation process a few important mistakes may happen, namely on IP rights, that can impact the future success of the business.

First, do not start from the end

When developing a figurative sign, a word trademark, an innovative technology that could be patentable or a software (source code), the first recommended step is to look into how to protect those creations, before showing it to third parties, namely investors or VC’s. This mistake is specially made on trademarks, as many times the entrepreneurs have already invested on the development of a logo and/or a trademark, they use it on their email signature, on their business presentations, but they have never registered the trademark as an IP right.

A non registered trademark is a common mistake and opens the door to others to copy it and to acquire (legally) rights over such distinctive sign. On the other hand, the lack of prior searches on preexisting IP rights may lead to trademark infringement, meaning that your amazing trademark is in fact infringing a preexisting trademark that you were not aware of.

Second, know what you are protecting

Basic mistake arises from those who did registered the trademark, but in a wrong or insufficient way: it is very common to see startups applying for a word trademark having a figurative element, when instead a trademark must be protected “as a whole” with their both signs (word and figurative element) in order to maximize the range of legal protection of your IP right.

Third, avoid the “classification nightmare”

The full comprehension and knowledge of the goods and services for which you apply for a trademark is decisive. It is strongly advisable for startup to have (at least) a medium term view of the business and request, on the trademark application, the full range of goods and services that they could sell or provide in the future and not only a short term view. Why? Because once the trademark application is granted it cannot be amended or added with additional goods and services. Only by requesting a new trademark application with all the costs involved in such operation.

The correct classification is crucial and decisive for a correct protection of your IP asset, especially on high technological startups where most of the time the high added value of the business arises from their IP.

On a brief, do not neglect IP, before is too late.

The author of this post is Josè Varanda

Schreiben Sie an Chiara

MetaBirkins NFT found to infringe Hermes trademark

22 März 2023

-

USA

- Geistiges Eigentum

‘’Made in Italy” is synonymous of high productive and aesthetic quality and represents an added value, in the international market, for different kind of products, from foodstuffs to clothing, automotive and furniture. In recent years, in Italy, a number of initiatives have been taken at the regulatory level to ensure its promotion, valorization and protection.

In 2024 came into force law no. 206/2023, referred to as the ‘New Made in Italy Law’, followed on 3 July 2024 by the related implementing Decree, by which the Ministry of Enterprise and Made in Italy (hereinafter the ‘Ministry’) introduced relevant provisions including the ones related to an official mark attesting the Italian origin of goods, the fight against counterfeiting (in particular in criminal law), and the promotion of the use of blockchain technology to protect production chains.

Among the new measures, there are specific rules for the protection of trademarks – with at least 50 years of registration or use in Italy – of particular national interest and value (hereinafter “Trademark/s”). The aim of such provisions is to safeguard the heritage represented by Italian trademarks with a long-standing presence on the market, preventing their extinction and guaranteeing their use by companies linked to the Italian territory.

Measures to guarantee the continuity

In order to protect the Trademarks, two distinct possibilities are envisaged

- Notification by companies

The first consists of the takeover by the Ministry of the ownership of Trademarks of companies that will cease their activities. In this regard, the Decree provides that a company owner or licensee of a trademark registered for at least 50 years, or for which it is possible to prove continuous use for at least 50 years, intending to cease its activity definitively, must notify the Ministry in advance of the plan to cease its activity, indicating, in particular, the economic, financial or technical reasons that impose the cessation. Upon receipt of this notification, the Ministry is entitled to take over ownership of the trademark without charge if the trademark has not been assigned for consideration by the owner or licensee company.

This procedure, in particular, is newly implemented, being applicable as of 2 December 2024.

- Revocation for non-use

The second possibility concerns Trademarks suspected of not being used for at least 5 years. In such case, the Ministry may file before the Italian Patent and Trademark Office an application for revocation for non-use and, if the application is granted, proceed with registering the Trademark in its name.

Trademarks of national interest owned by the Ministry will be announced on its Web site https://www.mimit.gov.it/it/impresa/competitivita-e-nuove-imprese/proprieta-industriale/marchi-di-interesse-storico/elenco-marchi.

As of 27 January 2025, one month after the applicability of the procedures at issue in the list are the following:

- INNOCENTI – Application number 302023000141171

- AUTOBIANCHI – Application number 302023000141189

Free licences for Italian or foreign companies wishing to invest in Italy

The Ministry is authorized to use the Trademarks, licensing them exclusively in favor of companies, including foreign ones, that intend to invest in Italy or transfer production activities located abroad to Italy.

In particular, Italian and foreign companies planning to produce in Italy may apply for a licence to use the above-mentioned Trademarks. The application shall contain specific details regarding the planned investment project, with a focus on the employment impact of the same.

Should the Ministry accept the application, the company will be granted a 10-year free licence, renewable on condition that the company maintains production activities within the national borders.

It is to be noted that, in the event that the company interrupts its activities or relocates its plants outside the Italian territory, the licence contract may be terminated immediately.

What’s next?

The recent regulatory measures are aimed, on the one hand, at keeping alive traditional brands that have been used in Italy for many years and, on the other hand, at allowing Italian and foreign companies to benefit from the incentive of free licences, if they decide to produce in Italy.

It will be interesting to monitor the business developments of these provisions in the coming months, in which the list of Trademarks owned by the Ministry will become longer.

Summary

Artist Mason Rothschild created a collection of digital images named “MetaBirkins”, each of which depicted a unique image of a blurry faux-fur covered the iconic Hermès bags, and sold them via NFT without any (license) agreement with the French Maison. HERMES brought its trademark action against Rothschild on January 14, 2022.

A Manhattan federal jury of nine persons returned after the trial a verdict stating that Mason Rothschild’s sale of the NFT violated the HERMES’ rights and committed trademark infringement, trademark dilution, and cybersquatting (through the use of the domain name “www.metabirkins.com”) because the US First Amendment protection could not apply in this case and awarded HERMES the following damages: 110.000 US$ as net profit earned by Mason Rothschild and 23.000 US$ because of cybersquatting.

The sale of approx. 100 METABIRKIN NFTs occurred after a broad marketing campaign done by Mason Rothschild on social media.

Rothschild’s defense was that digital images linked to NFT “constitute a form of artistic expression” i.e. a work of art protected under the First Amendment and similar to Andy Wahrhol’s paintings of Campbell’s soup cans. The aim of the defense was to have the “Rogers” legal test (so-called after the case Rogers vs Grimaldi) applied, according to which artists are entitled to use trademarks without permission as long as the work has an artistic value and is not misleading the consumers.

NFTs are digital record (a sort of “digital deed”) of ownership typically recorded in a publicly accessible ledger known as blockchain. Rothschild also commissioned computer engineers to operationalize a “smart contract” for each of the NFTs. A smart contract refers to a computer code that is also stored in the blockchain and that determines the name of each of the NFTs, constrains how they can be sold and transferred, and controls which digital files are associated with each of the NFTs.

The smart contract and the NFT can be owned by two unrelated persons or entities, like in the case here, where Rothschild maintained the ownership of the smart contract but sold the NFT.

“Individuals do not purchase NFTs to own a “digital deed” divorced to any other asset: they buy them precisely so that they can exclusively own the content associated with the NFT” (in this case the digital images of the MetaBirkin”), we can read in the Opinion and Order. The relevant consumers did not distinguish the NFTs offered by Rothschild from the underlying MetaBirkin image associated to the NFT.

The question was whether or not there was a genuine artistic expression or rather an unlawful intent to cash in on an exclusive valuable brand name like HERMES.

Mason Rothschild’s appeal to artistic freedom was not considered grounded since it came out that Rothschild was pursuing a commercial rather than an artistic end, further linking himself to other famous brands: Rothschild remarked that “MetaBirkins NFTs might be the next blue chip”. Insisting that he “was sitting on a gold mine” and referring to himself as “marketing king”, Rothschild “also discussed with his associates further potential future digital projects centered on luxury projects such watch NFTs called “MetaPateks” and linked to the famous Swiss luxury watches Patek Philippe.

TAKE AWAY: This is the first US decision on NFT and IP protection for trademarks.

The debate (i) between the protection of the artistic work and the protection of the trademark or other industrial property rights or (ii) between traditional artistic work and subsequent digital reinterpretation by a third party other than the original author, will lead to other decisions (in Italy, we recall the injunction order issued on 20-7-2022 by the Court of Rome in favour of the Juventus football team against the company Blockeras, producer of NFT associated with collectible digital figurines depicting the footballer Bobo Vieri, without Juventus‘ licence or authorisation). This seems to be a similar phenomenon to that which gave rise some 15 years ago to disputes between trademark owners and owners of domain names incorporating those trademarks. For the time being, trademark and IP owners seem to have the upper hand, especially in disputes that seem more commercial than artistic.

For an assessment of the importance and use of NFT and blockchain in association also with IP rights, you can read more here.

Zusammenfassung

Anhand der Geschichte von Nike, die sich aus der Biografie des Gründers Phil Knight ableitet, lassen sich einige Lehren für internationale Vertriebsverträge ziehen: Wie man den Vertrag aushandelt, die Vertragsdauer festlegt, die Exklusivität und die Geschäftsziele definiert und die richtige Art der Streitschlichtung bestimmt.

Worüber ich in diesem Artikel spreche

- Der Streit zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger und die Geburt von Nike

- Wie man eine internationale Vertriebsvereinbarung aushandelt

- Vertragliche Exklusivität in einer Handelsvertriebsvereinbarung

- Mindestumsatzklauseln in Vertriebsverträgen

- Vertragsdauer und Kündigungsfrist

- Eigentum an Marken in Handelsverträgen

- Die Bedeutung der Mediation bei internationalen Handelsverträgen

- Streitbeilegungsklauseln in internationalen Verträgen

- Wie wir Ihnen helfen können

Der Streit zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger und die Geburt von Nike

Warum ist die berühmteste Sportbekleidungsmarke der Welt Nike und nicht Onitsuka Tiger?

Die Biographie des Nike-Schöpfers Phil Knight mit dem Titel “Shoe Dog” gibt hierauf antworten und ist nicht nur für Liebhaber des Genres eine absolut empfehlenswerte Lektüre.

Bewegt von seiner Leidenschaft für den Laufsport und seiner Intuition, dass es auf dem amerikanischen Sportschuhmarkt, der damals von Adidas dominiert wurde, eine Lücke gab, importierte Knight 1964 als erster überhaupt eine japanische Sportschuhmarke, Onitsuka Tiger, in die USA. Mit diesen Sportschuhen konnte sich Knight innerhalb von 6 Jahren einen Marktanteil von satten 70 % sichern.

Das von Knight und seinem ehemaligen College-Trainer Bill Bowerman gegründete Unternehmen hieß damals noch Blue Ribbon Sports.

Die Geschäftsbeziehung zwischen Blue Ribbon-Nike und dem japanischen Hersteller Onitsuka Tiger gestaltete sich trotz der sehr guten Verkaufszahlen und den postiven Wachstumsaussichten von Beginn an als sehr turbulent.

Als Knight dann kurz nach der Vertragsverlängerung mit dem japanischen Hersteller erfuhr, dass Onitsuka in den USA nach einem anderen Vertriebspartner Ausschau hielt , beschloss Knight – aus Angst, vom Markt ausgeschlossen zu werden – sich seinerseits mit einem anderen japanischen Lieferanten zusammenzutun und seine eigene Marke zu gründen. Damit war die spätere Weltmarke Nike geboren.

Als der japanische Hersteller Onitsuka von dem Nike-Projekt erfuhr, verklagte dieser Blue Ribbon wegen Verstoß gegen das Wettbewerbsverbot, welches dem Vertriebshändler die Einfuhr anderer in Japan hergestellter Produkte untersagte, und beendete die Geschäftsbeziehung mit sofortiger Wirkung.

Blue Ribbon führte hiergegen an, dass der Verstoß von dem Hersteller Onitsuka Tiger ausging, der sich bereits als der Vertrag noch in Kraft war und die Geschäfte mehr als gut liefen mit anderen potenziellen Vertriebshändlern getroffen hatte.

Diese Auseinandersetzung führte zu zwei Gerichtsverfahren, eines in Japan und eines in den USA, die der Geschichte von Nike ein vorzeitiges Ende hätten setzen können.

Zum Glück (für Nike) entschied der amerikanische Richter zu Gunsten des Händlers und der Streit wurde mit einem Vergleich beendet: Damit begann für Nike die Reise, die sie 15 Jahre später zur wichtigsten Sportartikelmarke der Welt machen sollte.

Wir werden sehen, was uns die Geschichte von Nike lehrt und welche Fehler bei einem internationalen Vertriebsvertrag tunlichst vermieden werden sollten.

Wie verhandelt man eine internationale Handelsvertriebsvereinbarung?

In seiner Biografie schreibt Knight, dass er bald bedauerte, die Zukunft seines Unternehmens an eine eilig verfasste, wenige Zeilen umfassende Handelsvereinbarung gebunden zu haben, die am Ende einer Sitzung zur Aushandlung der Erneuerung des Vertriebsvertrags geschlossen wurde.

Was beinhaltete diese Vereinbarung?

Die Vereinbarung sah lediglich die Verlängerung des Rechts von Blue Ribbon vor, die Produkte in den USA exklusiv zu vertreiben, und zwar für weitere drei Jahre.

In der Praxis kommt es häufig vor, dass sich internationale Vertriebsverträge auf mündliche Vereinbarungen oder sehr einfache Vertragswerke mit kurzer Dauer beschränken. Die übliche Erklärung dafür ist, dass es auf diese Weise möglich ist, die Geschäftsbeziehung zu testen, ohne die vertragliche Bindung zu eng werden zu lassen.

Diese Art, Geschäfte zu machen, ist jedoch nicht zu empfehlen und kann sogar gefährlich werden: Ein Vertrag sollte niemals als Last oder Zwang angesehen werden, sondern als Garantie für die Rechte beider Parteien. Einen schriftlichen Vertrag nicht oder nur sehr übereilt abzuschließen, bedeutet, grundlegende Elemente der künftigen Beziehung, wie die, die zum Streit zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger führten, ohne klare Vereinbarungen zu belassen: Hierzu gehören Aspekte wie Handelsziele, Investitionen, das Eigentum an Marken – um nur einige zu benennen.

Handelt es sich zudem um einen internationalen Vertrag, ist die Notwendigkeit einer vollständigen und ausgewogenen Vereinbarung noch größer, da in Ermangelung von Vereinbarungen zwischen den Parteien oder in Ergänzung zu diesen Vereinbarungen ein Recht zur Anwendung kommt, mit dem eine der Parteien nicht vertraut ist, d. h. im Allgemeinen das Recht des Landes, in dem der Händler seinen Sitz hat.

Auch wenn Sie sich nicht in einer Blue-Ribbon-Situation befinden, in der es sich um einen Vertrag handelt, von dem die Existenz des Unternehmens abhängt, sollten internationale Verträge stets mit Hilfe eines fachkundigen Anwalts besprochen und ausgehandelt werden, der das auf den Vertrag anwendbare Recht kennt und dem Unternehmer helfen kann, die wichtigen Vertragsklauseln zu ermitteln und auszuhandeln.

Territoriale Exklusivität, kommerzielle Ziele und Mindestumsatzziele

Anlass für den Konflikt zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger war zunächst einmal die Bewertung der Absatzentwicklung auf dem US-Markt.

Onitsuka argumentierte, dass der Umsatz unter dem Potenzial des US-Marktes liege, während nach Angaben von Blue Ribbon die Verkaufsentwicklung sehr positiv sei, da sich der Umsatz bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt jedes Jahr verdoppelt habe und ein bedeutender Anteil des Marktsektors erobert worden sei.

Als Blue Ribbon erfuhr, dass Onituska andere Kandidaten für den Vertrieb seiner Produkte in den USA prüfte, und befürchtete, damit bald vom Markt verdrängt zu werden , bereitete Blue Ribbon die Marke Nike als Plan B vor: Als der japanische Hersteller diese Marke entdeckte , kam es zu einem Rechtsstreit zwischen den Parteien, der zu einem Eklat führte.

Der Streit hätte vielleicht vermieden werden können, wenn sich die Parteien auf kommerzielle Ziele geeinigt hätten und der Vertrag eine in Alleinvertriebsvereinbarungen übliche Klausel enthalten hätte, d.h. ein Mindestabsatzziel für den Vertriebshändler.

In einer Alleinvertriebsvereinbarung gewährt der Hersteller dem Händler einen starken Gebietsschutz für die Investitionen, die der Händler zur Erschließung des zugewiesenen Marktes tätigt.

Um dieses Zugeständnis der Exklusivität auszugleichen, ist es üblich, dass der Hersteller vom Vertriebshändler einen so genannten garantierten Mindestumsatz oder ein Mindestziel verlangt, das der Vertriebshändler jedes Jahr erreichen muss, um den ihm gewährten privilegierten Status zu behalten.

Für den Fall, dass das Mindestziel nicht erreicht wird, sieht der Vertrag dann in der Regel vor, dass der Hersteller das Recht hat, vom Vertrag zurückzutreten (bei einem unbefristeten Vertrag) oder den Vertrag nicht zu verlängern (bei einem befristeten Vertrag) oder aber auch die Gebietsexklusivität aufzuheben bzw. einzuschränken.

Der Vertrag zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger sah derartige Zielvorgaben nicht vor – und das nachdem er gerade erst um drei Jahre verlängert wurde. Hinzukam, dass sich die Parteien bei der Bewertung der Ergebnisse des Vertriebshändlers nicht einig waren. Es stellt sich daher die Frage: Wie können in einem Mehrjahresvertrag Mindestumsatzziele vorgesehen werden?

In Ermangelung zuverlässiger Daten verlassen sich die Parteien häufig auf vorher festgelegte prozentuale Erhöhungsmechanismen: + 10 % im zweiten Jahr, + 30 % im dritten Jahr, + 50 % im vierten Jahr und so weiter.