-

Italien

Internationale Vertretungsverträge nach italienischem Recht

19 September 2022

- Agentur

- Vertrieb

Many people think that the non-disclosure agreement (NDA) is the one and only necessary precaution in a negotiation. This is wrong, because this agreement only refers to a facet of the business relationship that the parties want to discuss or manage.

Why is it important

The function of the NDA is to maintain the confidentiality of certain information that the parties intend to exchange and to prevent it from being used for purposes on which the parties did not agree. However, many aspects of the negotiation are not regulated in the NDA.

The main issues that the parties should agree on in writing are the following:

- why do the parties want to exchange information?

- what is the ultimate scope to be achieved?

- on what general points do the parties already agree?

- how long will negotiations last?

- who will participate in the negotiations, and with what powers?

- what documents and information will be shared?

- are there any exclusivity and/or non-compete obligations during and after the negotiation?

- what law applies to the negotiations and how are potential disputes resolved?

If these questions are not answered, it is likely that misunderstandings and disputes will arise over time, especially in lengthy and complex negotiations with foreign counterparts.

How to proceed?

- It is advisable that the above agreements be set down in a Letter of Intent („LoI“) or Memorandum of Understanding („MoU“). These are preliminary agreements whose function is determining the scope of future negotiations, the timetable, and the rules to be observed during and after the negotiations.

Common objection

„These are non-binding contracts, so what is the point of using them if the parties are free not to comply?

- Some covenants may be binding (exclusivity during negotiation, non-competition, dispute settlement agreements), and some may not (with the freedom to conclude or not to conclude the agreement).

- In any case, agreeing on the negotiating roadmap is an advantage over operating without having set the negotiating guidelines.

What happens if no agreement is reached?

- The MoU usually expressly provides for each party to be free not to finalize the negotiation as long as that party behaves, keeps acting in good faith during the negotiations and preserves the other party’s rights.

- It should be noted that in case of early or unjustified termination of the negotiations by one of the parties, the other party may be entitled to damages (so-called pre-contractual liability) if the agreement and/or the law applicable to the contract so provide.

Then, when should a non-disclosure agreement be concluded?

- It can be executed at the same time as the MoU / LoI or immediately afterwards so that the specification of confidential information, the way it is used, the duration of confidentiality obligations, etc. are defined in a way that is consistent with the project the parties have agreed upon.

For more information on the content of confidentiality agreements, see this article.

Wann ist ein Agenturvertrag als “international” zu betrachten?

Nach den in Italien geltenden Regeln des internationalen Privatrechts (Art. 1 Reg. 593/08 “Rom I”) gilt ein Vertrag als ”international”, wenn “kollisionsrechtliche Situationen” vorliegen.

Die Situationen, die bei Handelsvertreterverträgen häufiger zu einer Rechtskollision führen – und sie damit „international“ machen – sind (i) der Sitz des Auftraggebers in einem anderen Land als dem des Handelsvertreters oder (ii) die Erfüllung des Vertrags im Ausland, auch wenn sich der Sitz des Auftraggebers und des Handelsvertreters im selben Land befinden.

Wann ist das italienische Recht auf einen Handelsvertretervertrag anwendbar?

Nach der “Rom I”-Verordnung kann auf einen internationalen Handelsvertretervertrag grundsätzlich italienisches Recht angewandt werden, (i) wenn es von den Parteien als das für den Vertrag maßgebliche Recht gewählt wurde (entweder ausdrücklich oder wie in Artikel 3 vorgesehen); oder (ii) wenn der Handelsvertreter seinen Wohnsitz oder Sitz in Italien hat (gemäß dem Konzept des “Wohnsitzes” in Artikel 19).

Was sind die wichtigsten Vorschriften für Handelsvertreterverträge in Italien?

Die wesentlichen Vorschriften für Handelsvertreterverträge in Italien, insbesondere im Hinblick auf die Auftraggeber-Vertreter-Beziehung, finden sich hauptsächlich in den Artikeln 1742 bis 1753 des Zivilgesetzbuches. Diese Vorschriften wurden nach der Verabschiedung der Richtlinie 653/86/EG wiederholt geändert.

Welche Rolle spielen die Tarifverträge?

Seit vielen Jahren regeln die Tarifverträge (CBA) auch die Vertreterverträge. Dabei handelt es sich um Vereinbarungen, die in regelmäßigen Abständen zwischen den Verbänden der Auftraggeber und der Auftragnehmer in verschiedenen Sektoren (Produktion, Handel und andere) getroffen werden.

Unter dem Gesichtspunkt der Rechtswirksamkeit kann zwischen zwei Arten von GAV unterschieden werden, nämlich GAV mit Gesetzeskraft (erga omnes) – deren Regeln jedoch recht weit gefasst sind und daher nur einen begrenzten Anwendungsbereich haben – und GAV mit Vertragscharakter („di diritto comune“), die im Laufe der Jahre immer wieder unterzeichnet wurden und nur die Auftraggeber und Beauftragten binden sollen, die Mitglieder dieser Verbände sind.

Im Allgemeinen zielen die KVA auf die Umsetzung der Vorschriften des Zivilgesetzbuches und der Richtlinie 653/86 ab. Allerdings weichen vertragliche KVAs häufig von diesen Regeln ab, und einige Abweichungen sind erheblich. So kann ein Unternehmer beispielsweise das Gebiet des Handelsvertreters, die Vertragsprodukte, den Kundenkreis oder die Provision einseitig ändern. CBAs legen die Dauer der Kündigungsfrist bei der Beendigung von unbefristeten Verträgen teilweise anders fest. CBAs haben ihre eigene Berechnung der Vergütung des Handelsvertreters für das nachvertragliche Wettbewerbsverbot. CBAs haben besondere Regelungen zur Kündigungsentschädigung.

Insbesondere im Hinblick auf die Entschädigung bei Vertragsbeendigung gab es ernsthafte Probleme mit der Übereinstimmung zwischen den CBAs und der Richtlinie 653/86/EG. Diese Fragen sind trotz einiger Urteile des EuGH nach wie vor ungelöst, da die ständige Rechtsprechung der italienischen Gerichte die Entschädigungsbestimmungen in den CBAs in Kraft hält.

Nach der Mehrzahl der wissenschaftlichen Stellungnahmen und der Rechtsprechung ist der geografische Anwendungsbereich der KNA auf das italienische Staatsgebiet beschränkt.

Daher gelten CBAs automatisch für Handelsvertreterverträge, die italienischem Recht unterliegen und vom Handelsvertreter in Italien ausgeführt werden; Bei vertraglichen CBAs ist jedoch eine weitere Bedingung, dass beide Parteien Mitglieder von Vereinigungen sind, die solche Vereinbarungen geschlossen haben. Einigen Gelehrten zufolge reicht es aus, wenn nur der Auftraggeber Mitglied eines solchen Verbandes ist.

Aber auch wenn solche kumulativen Bedingungen nicht vorliegen, können vertragliche GAV dennoch Anwendung finden, wenn im Leiharbeitsvertrag ausdrücklich auf sie Bezug genommen wird oder ihre Bestimmungen von den Parteien ständig eingehalten werden.

Welches sind die anderen wichtigen Anforderungen an Agenturverträge?

Der „Enasarco“

Enasarco ist eine privatrechtliche Stiftung, bei der Vertreter in Italien per Gesetz registriert sein müssen.

Die Enasarco-Stiftung verwaltet vor allem eine Zusatzrentenkasse für Bedienstete und einen Abfindungsfonds mit der Bezeichnung “FIRR” (für die Abfindung, die nach den in den Tarifverträgen der verschiedenen Sektoren festgelegten Kriterien berechnet wird).

In der Regel meldet der Auftraggeber eines “inländischen” Vertretungsvertrags den Vertreter bei der Enasarco an und zahlt während der gesamten Laufzeit des Vertretungsvertrags regelmäßig Beiträge an die beiden genannten Fonds.

Während jedoch die Anmeldung und der Beitrag zur Rentenkasse immer obligatorisch sind, da sie im Gesetz vorgesehen sind, sind die Beiträge zum FIRR nur für diejenigen Leiharbeitsverträge obligatorisch, die durch vertragliche Tarifverträge geregelt sind.

Welche Regeln gelten für internationale Agenturverträge?

Was die Registrierung bei der Enasarco betrifft, so sind die Rechts- und Verwaltungsvorschriften nicht so eindeutig. Das Arbeitsministerium hat jedoch im Jahr 2013 in Beantwortung einer konkreten Frage wichtige Klarstellungen vorgenommen (19.11.13 n.32).

Unter Bezugnahme auf die europäische Gesetzgebung (EG-Verordnung Nr. 883/2004 in der Fassung der Verordnung Nr. 987/2009) erklärte das Ministerium, dass die Registrierung bei der Enasarco in folgenden Fällen obligatorisch ist:

- vertreter, die im italienischen Hoheitsgebiet im Namen und für Rechnung italienischer oder ausländischer Auftraggeber mit Sitz oder Niederlassung in Italien tätig sind;

- italienische oder ausländische Vertreter, die in Italien im Namen und/oder für Rechnung italienischer oder ausländischer Auftraggeber mit oder ohne Sitz oder Büro in Italien tätig sind;

- vertreter, die in Italien wohnen und einen wesentlichen Teil ihrer Tätigkeit in Italien ausüben;

- vertreter, die nicht in Italien ansässig sind, aber ihren Interessenschwerpunkt in Italien haben;

- agenten, die gewöhnlich in Italien tätig sind, aber ihre Tätigkeit ausschließlich im Ausland ausüben, und zwar für einen Zeitraum von höchstens 24 Monaten.

Die vorgenannten Verordnungen gelten natürlich nicht für Verträge, die außerhalb der EU geschlossen werden sollen. Daher sollte von Fall zu Fall geprüft werden, ob internationale Verträge, die die Länder der Vertragsparteien binden, die Anwendung der italienischen Sozialversicherungsvorschriften vorsehen.

Handelskammer und Unternehmensregister

Jeder, der in Italien ein Unternehmen als Handelsvertreter gründen möchte, muss bei der örtlich zuständigen Handelskammer eine “SCIA” (Certified Notice of Business Start) einreichen. Die Handelskammer trägt dann den Handelsvertreter in das Unternehmensregister ein, wenn der Handelsvertreter als Unternehmen organisiert ist, andernfalls trägt sie den Handelsvertreter in eine spezielle Abteilung der „REA“ (Liste der Geschäfts- und Verwaltungsinformationen) derselben Kammer ein (siehe Gesetzesdekret Nr. 59 vom 26.3.2010, zur Umsetzung der Richtlinie 2006/123/EG „Dienstleistungsrichtlinie“).

Diese Formalitäten haben die frühere Eintragung in das Vermittlerverzeichnis („ruolo agenti“) ersetzt, die durch das genannte Gesetz abgeschafft wurde. Das neue Gesetz sieht darüber hinaus eine Reihe weiterer obligatorischer Anforderungen für Agenten vor, die eine Tätigkeit aufnehmen wollen. Diese Anforderungen betreffen die Ausbildung, die Erfahrung, ein sauberes Strafregister, usw.

Auch wenn die Nichteinhaltung der neuen Registrierungsvorschriften die Gültigkeit des Vertretungsvertrags nicht beeinträchtigt, sollte der Unternehmer dennoch prüfen, ob der italienische Vertreter registriert ist, bevor er ihn ernennt, da dies ohnehin eine zwingende Voraussetzung ist.

Gerichtsstand für Streitigkeiten (Art. 409 ff. der Zivilprozessordnung)

Gemäß Artikel 409 ff. der Zivilprozessordnung (ZPO) ist für den Fall, dass der Handelsvertreter seine vertraglichen Pflichten hauptsächlich als Einzelperson, wenn auch selbständig, erfüllt (so genannter “parasubordinato”, d. h. „halb untergeordneter“ Handelsvertreter) – vorausgesetzt, der Handelsvertretervertrag unterliegt italienischem Recht und die italienischen Gerichte sind zuständig – für alle Streitigkeiten aus dem Handelsvertretervertrag das Arbeitsgericht des Bezirks zuständig, in dem der Handelsvertreter seinen Wohnsitz hat (siehe Artikel 413 ZPO), und das Gerichtsverfahren wird nach ähnlichen Verfahrensregeln wie für arbeitsrechtliche Streitigkeiten durchgeführt.

Diese Regeln gelten grundsätzlich, wenn der Vertreter den Vertrag als Einzelperson oder Einzelunternehmer abschließt, während sie nach der Mehrheit der Wissenschaftler und der Rechtsprechung nicht gelten, wenn der Vertreter ein Unternehmen ist.

Die Anwendung der oben genannten Regeln auf die häufigsten Situationen in internationalen Vertretungsverträgen

Versuchen wir nun, die bisher beschriebenen Regeln auf die häufigsten Situationen in internationalen Vertretungsverträgen anzuwenden, wobei zu beachten ist, dass es sich dabei um einfache Beispiele handelt, während man in der “realen Welt” die Umstände jedes einzelnen Falles sorgfältig prüfen sollte.

- Italienischer Auftraggeber und ausländischer Vertreter – im Ausland zu erfüllender Vertrag

Italienisches Recht: Es gilt für den Vertrag, wenn die Parteien es gewählt haben, unbeschadet der (international zwingenden) Vorschriften der öffentlichen Ordnung (ordre public) des Landes, in dem der Vertreter seinen Sitz hat und seine Tätigkeit ausübt, gemäß der Verordnung Rom I.

CBAs: Sie regeln den Vertrag nicht automatisch (weil der Vertreter im Ausland tätig ist), sondern nur dann, wenn in dem Vertrag ausdrücklich auf sie Bezug genommen wird oder sie de facto Anwendung finden. Dies kann mehr oder weniger absichtlich geschehen, z. B. wenn ein italienischer Auftraggeber mit ausländischen Handelsvertretern die gleichen Vertragsformulare wie mit italienischen Handelsvertretern verwendet, die in der Regel zahlreiche Verweise auf die GAV enthalten.

Enasarco: In der Regel gibt es keine Registrierungs- oder Beitragspflichten für einen nicht-italienischen Vertreter, der seinen Wohnsitz im Ausland hat und seine vertraglichen Pflichten nur im Ausland erfüllt.

Handelskammer: Unter den oben genannten Umständen besteht keine Verpflichtung zur Registrierung.

Verfahrensvorschriften (Artikel 409 ff. CPC): Wenn für alle Streitigkeiten italienische Gerichte zuständig sind, kann ein ausländischer Vertreter, auch wenn es sich um eine Einzelperson oder einen Einzelunternehmer handelt, diese Bestimmung nicht nutzen, um den Fall vor die Gerichte seines eigenen Landes zu bringen. Dies liegt daran, dass es sich bei Art. 413 cpc um eine innerstaatliche Bestimmung über den Gerichtsstand handelt, die voraussetzt, dass sich der Sitz des Vertreters in Italien befindet. Außerdem sollten die Zuständigkeitsvorschriften des EU-Rechts Vorrang haben, wie der italienische Kassationsgerichtshof entschieden und wichtige Wissenschaftler festgestellt haben.

- Ausländischer Auftraggeber und italienischer Vertreter – in Italien zu erfüllender Vertrag

Italienisches Recht: Es ist auf den Vertrag anwendbar, wenn die Parteien eine Rechtswahl getroffen haben oder, auch wenn keine Rechtswahl getroffen wurde, weil der Vertreter seinen Wohnsitz oder Sitz in Italien hat.

CBAs: Diejenigen, die Rechtskraft (“erga omnes”) haben, sind für die Vereinbarung maßgeblich, während diejenigen, die Vertragscharakter haben, wahrscheinlich nicht automatisch gelten, da der ausländische Auftraggeber in der Regel kein Mitglied eines der italienischen Verbände ist, die einen CBA unterzeichnet haben. Sie könnten jedoch Anwendung finden, wenn sie in der Vereinbarung erwähnt werden oder de facto Anwendung finden.

Enasarco: Ein ausländischer Auftraggeber muss den italienischen Vertreter bei der Enasarco anmelden. Geschieht dies nicht, können Sanktionen und/oder Schadenersatzforderungen des Vertreters die Folge sein. Infolge einer solchen Registrierung muss der Unternehmer Beiträge zur Sozialversicherung leisten, während er nicht verpflichtet ist, Beiträge zum FIRR (Fonds für Abfindungen) zu leisten. Ein Unternehmer, der regelmäßig Beiträge zur Sozialversicherungskasse leistet, auch wenn diese nicht fällig sind, könnte jedoch so angesehen werden, als habe er die auf den Handelsvertretervertrag anwendbaren Tarifverträge stillschweigend akzeptiert.

Handelskammer: Der italienische Handelsvertreter muss bei der Handelskammer eingetragen sein. Der Auftraggeber sollte sich daher vergewissern, dass der Handelsvertreter diese Anforderung erfüllt, bevor er den Vertrag abschließt.

Verfahrensvorschriften (Art. 409 ff. CPC): Wenn italienische Gerichte zuständig sind (entweder nach Wahl der Parteien oder als Erfüllungsort der Dienstleistungen gemäß Verordnung 1215/12) und der Vertreter eine natürliche Person oder ein Einzelunternehmer mit Sitz in Italien ist, sollten diese Vorschriften gelten.

- Italienischer Auftraggeber und italienischer Vermittler – im Ausland zu erfüllender Vertrag

Italienisches Recht: Es ist auf den Vertrag anwendbar, wenn die Parteien eine Rechtswahl getroffen haben oder, in Ermangelung einer solchen, wenn der Vertreter seinen Wohnsitz oder Sitz in Italien hat.

CBAs: Sie würden nicht gelten (da der Vertreter im Ausland tätig ist), es sei denn, sie sind ausdrücklich im Vertrag erwähnt oder werden de facto angewandt.

Enasarco: Nach Auffassung des Arbeitsministeriums ist eine Registrierung obligatorisch, wenn der Vertreter, obwohl er im Ausland tätig ist, seinen Wohnsitz und einen wesentlichen Teil seiner Tätigkeit in Italien hat oder in Italien seinen Interessenschwerpunkt hat oder für einen Zeitraum von nicht mehr als 24 Monaten im Ausland tätig ist, sofern die EU-Verordnungen gelten. Soll der Handelsvertretervertrag in einem Nicht-EU-Land durchgeführt werden, muss von Zeit zu Zeit geprüft werden, ob eine Registrierung erforderlich ist.

Handelskammer: Ein Handelsvertreter, der seine Tätigkeit in Italien aufgenommen hat und sich dort niedergelassen hat, ist grundsätzlich verpflichtet, sich bei der Handelskammer registrieren zu lassen.

Verfahrensvorschriften (Artikel 409 ff. CPC): Diese Vorschriften gelten, wenn der Vertreter eine in Italien ansässige natürliche Person oder ein Einzelunternehmer ist und die italienische Gerichtsbarkeit vereinbart wurde.

- Ausländischer Auftraggeber und ausländischer Vertreter – in Italien zu erfüllender Vertrag

Italienisches Recht: Es ist grundsätzlich nur dann anwendbar, wenn es von den Parteien gewählt wurde.

GAV: Wenn die Vereinbarung italienischem Recht unterliegt, gelten die rechtsverbindlichen GAV, während die vertragsrelevanten GAV nicht gelten, es sei denn, sie werden ausdrücklich erwähnt oder de facto angewandt.

Enasarco: Nach Auffassung des Arbeitsministeriums kann bei Anwendung der EU-Verordnungen von einem ausländischen Auftraggeber eine Registrierung zugunsten eines im Ausland ansässigen Vertreters verlangt werden, wenn dieser Vertreter in Italien tätig ist oder seinen Interessenschwerpunkt in Italien hat. Andernfalls ist eine Einzelfallprüfung nach den geltenden Gesetzen erforderlich.

Handelskammer: Ein im Ausland niedergelassener Handelsvertreter ist grundsätzlich nicht verpflichtet, sich in Italien registrieren zu lassen. Die Angelegenheit könnte jedoch komplexer sein, wenn der Vertreter einen Sitz hat und seine Tätigkeit hauptsächlich in Italien ausübt. Solche Umstände können sich auch auf die Bestimmung des Rechts auswirken, das für den Handelsvertretervertrag gilt.

Verfahrensvorschriften (Artikel 409 ff. CPC): In Ermangelung einer anderen Rechtswahl könnten italienische Gerichte zuständig sein, da Italien der Ort der Leistungserbringung ist. Die vorgenannten Regeln sollten jedoch nicht gelten, wenn der Vertreter keinen Sitz oder Wohnsitz in Italien hat.

Abschließende Bemerkungen

Wir hoffen, dass diese Analyse, auch wenn sie nicht erschöpfend ist, dazu beitragen kann, die möglichen Folgen der Anwendung des italienischen Rechts auf einen internationalen Handelsvertretervertrag zu verstehen und bei der Ausarbeitung des Vertrages umsichtige Entscheidungen zu treffen. Wie immer empfehlen wir, sich nicht auf Standardvertragsformulare oder Präzedenzfälle zu verlassen, ohne alle Umstände des Einzelfalls gebührend berücksichtigt zu haben.

Zusammenfassung

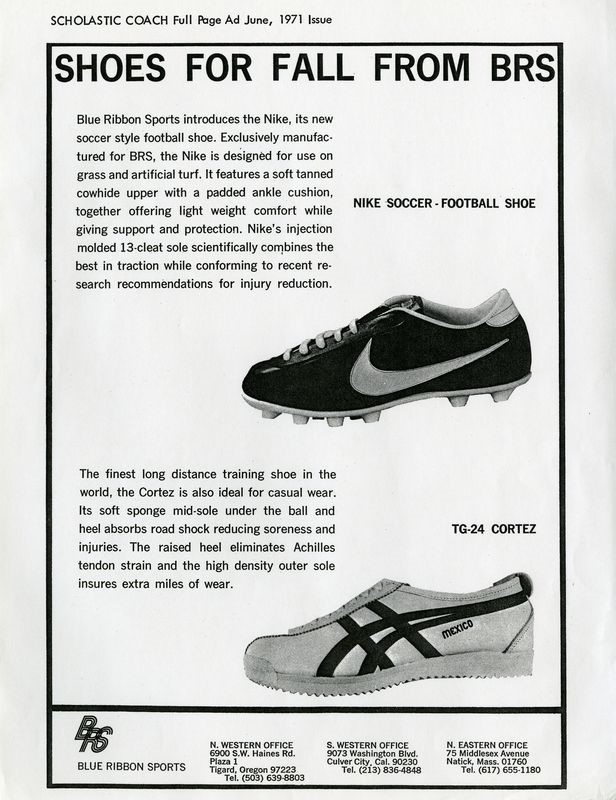

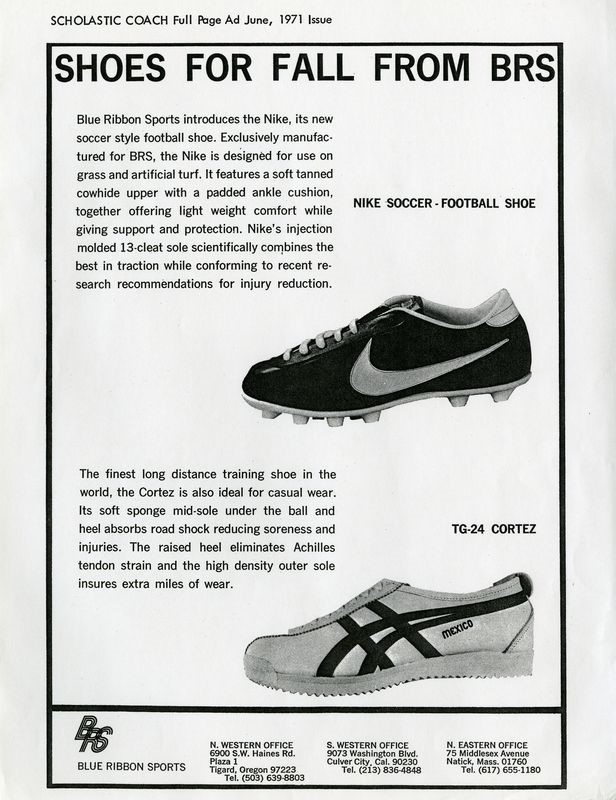

Anhand der Geschichte von Nike, die sich aus der Biografie des Gründers Phil Knight ableitet, lassen sich einige Lehren für internationale Vertriebsverträge ziehen: Wie man den Vertrag aushandelt, die Vertragsdauer festlegt, die Exklusivität und die Geschäftsziele definiert und die richtige Art der Streitschlichtung bestimmt.

Worüber ich in diesem Artikel spreche

- Der Streit zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger und die Geburt von Nike

- Wie man eine internationale Vertriebsvereinbarung aushandelt

- Vertragliche Exklusivität in einer Handelsvertriebsvereinbarung

- Mindestumsatzklauseln in Vertriebsverträgen

- Vertragsdauer und Kündigungsfrist

- Eigentum an Marken in Handelsverträgen

- Die Bedeutung der Mediation bei internationalen Handelsverträgen

- Streitbeilegungsklauseln in internationalen Verträgen

- Wie wir Ihnen helfen können

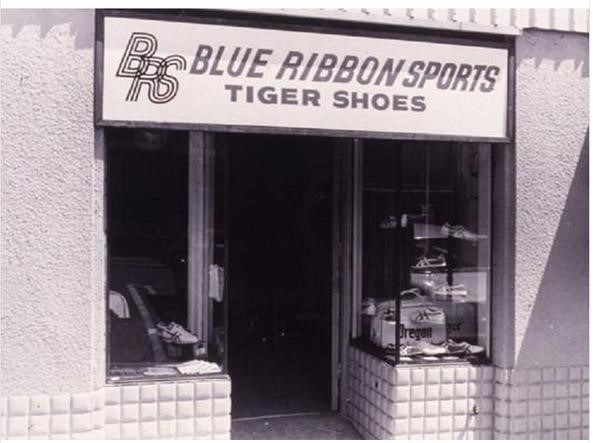

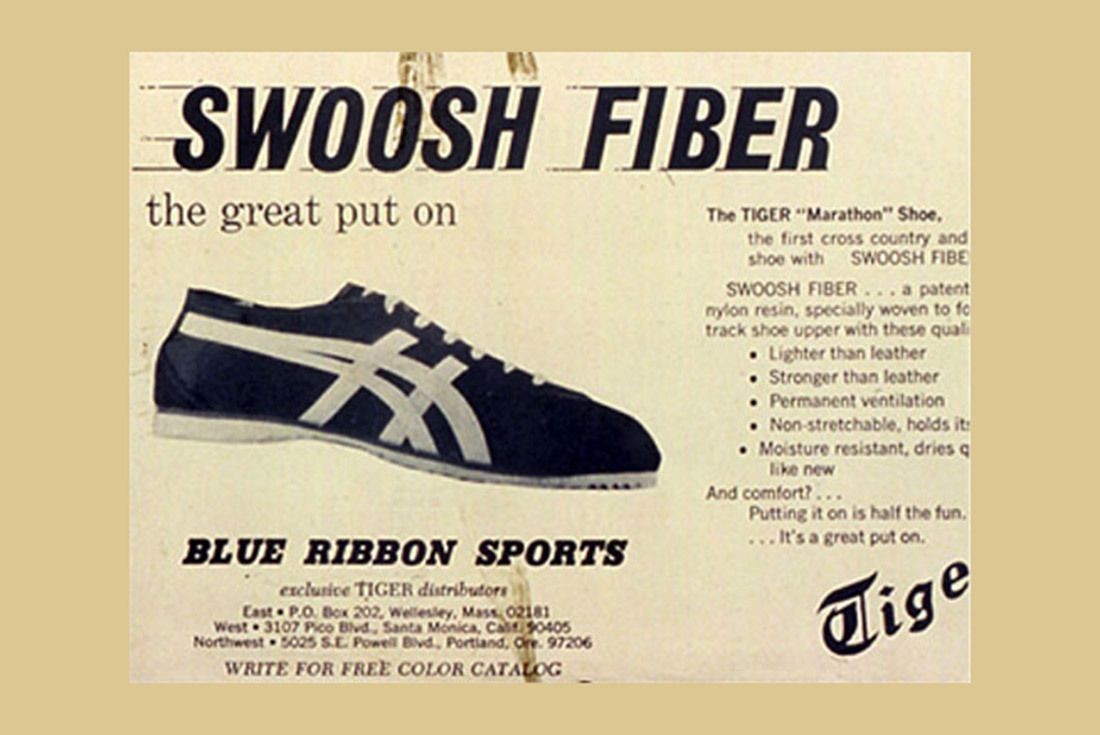

Der Streit zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger und die Geburt von Nike

Warum ist die berühmteste Sportbekleidungsmarke der Welt Nike und nicht Onitsuka Tiger?

Die Biographie des Nike-Schöpfers Phil Knight mit dem Titel “Shoe Dog” gibt hierauf antworten und ist nicht nur für Liebhaber des Genres eine absolut empfehlenswerte Lektüre.

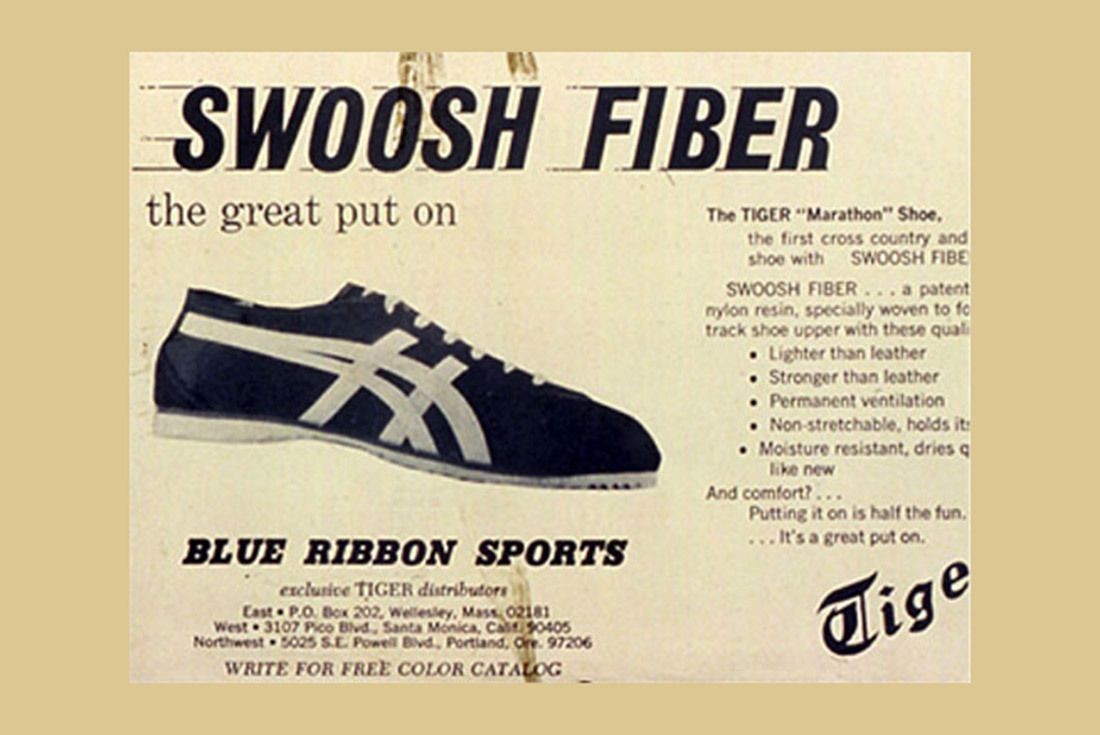

Bewegt von seiner Leidenschaft für den Laufsport und seiner Intuition, dass es auf dem amerikanischen Sportschuhmarkt, der damals von Adidas dominiert wurde, eine Lücke gab, importierte Knight 1964 als erster überhaupt eine japanische Sportschuhmarke, Onitsuka Tiger, in die USA. Mit diesen Sportschuhen konnte sich Knight innerhalb von 6 Jahren einen Marktanteil von satten 70 % sichern.

Das von Knight und seinem ehemaligen College-Trainer Bill Bowerman gegründete Unternehmen hieß damals noch Blue Ribbon Sports.

Die Geschäftsbeziehung zwischen Blue Ribbon-Nike und dem japanischen Hersteller Onitsuka Tiger gestaltete sich trotz der sehr guten Verkaufszahlen und den postiven Wachstumsaussichten von Beginn an als sehr turbulent.

Als Knight dann kurz nach der Vertragsverlängerung mit dem japanischen Hersteller erfuhr, dass Onitsuka in den USA nach einem anderen Vertriebspartner Ausschau hielt , beschloss Knight – aus Angst, vom Markt ausgeschlossen zu werden – sich seinerseits mit einem anderen japanischen Lieferanten zusammenzutun und seine eigene Marke zu gründen. Damit war die spätere Weltmarke Nike geboren.

Als der japanische Hersteller Onitsuka von dem Nike-Projekt erfuhr, verklagte dieser Blue Ribbon wegen Verstoß gegen das Wettbewerbsverbot, welches dem Vertriebshändler die Einfuhr anderer in Japan hergestellter Produkte untersagte, und beendete die Geschäftsbeziehung mit sofortiger Wirkung.

Blue Ribbon führte hiergegen an, dass der Verstoß von dem Hersteller Onitsuka Tiger ausging, der sich bereits als der Vertrag noch in Kraft war und die Geschäfte mehr als gut liefen mit anderen potenziellen Vertriebshändlern getroffen hatte.

Diese Auseinandersetzung führte zu zwei Gerichtsverfahren, eines in Japan und eines in den USA, die der Geschichte von Nike ein vorzeitiges Ende hätten setzen können.

Zum Glück (für Nike) entschied der amerikanische Richter zu Gunsten des Händlers und der Streit wurde mit einem Vergleich beendet: Damit begann für Nike die Reise, die sie 15 Jahre später zur wichtigsten Sportartikelmarke der Welt machen sollte.

Wir werden sehen, was uns die Geschichte von Nike lehrt und welche Fehler bei einem internationalen Vertriebsvertrag tunlichst vermieden werden sollten.

Wie verhandelt man eine internationale Handelsvertriebsvereinbarung?

In seiner Biografie schreibt Knight, dass er bald bedauerte, die Zukunft seines Unternehmens an eine eilig verfasste, wenige Zeilen umfassende Handelsvereinbarung gebunden zu haben, die am Ende einer Sitzung zur Aushandlung der Erneuerung des Vertriebsvertrags geschlossen wurde.

Was beinhaltete diese Vereinbarung?

Die Vereinbarung sah lediglich die Verlängerung des Rechts von Blue Ribbon vor, die Produkte in den USA exklusiv zu vertreiben, und zwar für weitere drei Jahre.

In der Praxis kommt es häufig vor, dass sich internationale Vertriebsverträge auf mündliche Vereinbarungen oder sehr einfache Vertragswerke mit kurzer Dauer beschränken. Die übliche Erklärung dafür ist, dass es auf diese Weise möglich ist, die Geschäftsbeziehung zu testen, ohne die vertragliche Bindung zu eng werden zu lassen.

Diese Art, Geschäfte zu machen, ist jedoch nicht zu empfehlen und kann sogar gefährlich werden: Ein Vertrag sollte niemals als Last oder Zwang angesehen werden, sondern als Garantie für die Rechte beider Parteien. Einen schriftlichen Vertrag nicht oder nur sehr übereilt abzuschließen, bedeutet, grundlegende Elemente der künftigen Beziehung, wie die, die zum Streit zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger führten, ohne klare Vereinbarungen zu belassen: Hierzu gehören Aspekte wie Handelsziele, Investitionen, das Eigentum an Marken – um nur einige zu benennen.

Handelt es sich zudem um einen internationalen Vertrag, ist die Notwendigkeit einer vollständigen und ausgewogenen Vereinbarung noch größer, da in Ermangelung von Vereinbarungen zwischen den Parteien oder in Ergänzung zu diesen Vereinbarungen ein Recht zur Anwendung kommt, mit dem eine der Parteien nicht vertraut ist, d. h. im Allgemeinen das Recht des Landes, in dem der Händler seinen Sitz hat.

Auch wenn Sie sich nicht in einer Blue-Ribbon-Situation befinden, in der es sich um einen Vertrag handelt, von dem die Existenz des Unternehmens abhängt, sollten internationale Verträge stets mit Hilfe eines fachkundigen Anwalts besprochen und ausgehandelt werden, der das auf den Vertrag anwendbare Recht kennt und dem Unternehmer helfen kann, die wichtigen Vertragsklauseln zu ermitteln und auszuhandeln.

Territoriale Exklusivität, kommerzielle Ziele und Mindestumsatzziele

Anlass für den Konflikt zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger war zunächst einmal die Bewertung der Absatzentwicklung auf dem US-Markt.

Onitsuka argumentierte, dass der Umsatz unter dem Potenzial des US-Marktes liege, während nach Angaben von Blue Ribbon die Verkaufsentwicklung sehr positiv sei, da sich der Umsatz bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt jedes Jahr verdoppelt habe und ein bedeutender Anteil des Marktsektors erobert worden sei.

Als Blue Ribbon erfuhr, dass Onituska andere Kandidaten für den Vertrieb seiner Produkte in den USA prüfte, und befürchtete, damit bald vom Markt verdrängt zu werden , bereitete Blue Ribbon die Marke Nike als Plan B vor: Als der japanische Hersteller diese Marke entdeckte , kam es zu einem Rechtsstreit zwischen den Parteien, der zu einem Eklat führte.

Der Streit hätte vielleicht vermieden werden können, wenn sich die Parteien auf kommerzielle Ziele geeinigt hätten und der Vertrag eine in Alleinvertriebsvereinbarungen übliche Klausel enthalten hätte, d.h. ein Mindestabsatzziel für den Vertriebshändler.

In einer Alleinvertriebsvereinbarung gewährt der Hersteller dem Händler einen starken Gebietsschutz für die Investitionen, die der Händler zur Erschließung des zugewiesenen Marktes tätigt.

Um dieses Zugeständnis der Exklusivität auszugleichen, ist es üblich, dass der Hersteller vom Vertriebshändler einen so genannten garantierten Mindestumsatz oder ein Mindestziel verlangt, das der Vertriebshändler jedes Jahr erreichen muss, um den ihm gewährten privilegierten Status zu behalten.

Für den Fall, dass das Mindestziel nicht erreicht wird, sieht der Vertrag dann in der Regel vor, dass der Hersteller das Recht hat, vom Vertrag zurückzutreten (bei einem unbefristeten Vertrag) oder den Vertrag nicht zu verlängern (bei einem befristeten Vertrag) oder aber auch die Gebietsexklusivität aufzuheben bzw. einzuschränken.

Der Vertrag zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger sah derartige Zielvorgaben nicht vor – und das nachdem er gerade erst um drei Jahre verlängert wurde. Hinzukam, dass sich die Parteien bei der Bewertung der Ergebnisse des Vertriebshändlers nicht einig waren. Es stellt sich daher die Frage: Wie können in einem Mehrjahresvertrag Mindestumsatzziele vorgesehen werden?

In Ermangelung zuverlässiger Daten verlassen sich die Parteien häufig auf vorher festgelegte prozentuale Erhöhungsmechanismen: + 10 % im zweiten Jahr, + 30 % im dritten Jahr, + 50 % im vierten Jahr und so weiter.

Das Problem bei diesem Automatismus ist, dass dadurch Zielvorgaben vereinbart werden, die nicht auf tatsächlichen Daten über die künftige Entwicklung der Produktverkäufe, der Verkäufe der Wettbewerber und des Marktes im Allgemeinen basieren , und die daher sehr weit von den aktuellen Absatzmöglichkeiten des Händlers entfernt sein können.

So wäre beispielsweise die Anfechtung des Vertriebsunternehmens wegen Nichterfüllung der Zielvorgaben für das zweite oder dritte Jahr in einer rezessiven Wirtschaft sicherlich eine fragwürdige Entscheidung, die wahrscheinlich zu Meinungsverschiedenheiten führen würde.

Besser wäre eine Klausel, mit der Ziele von Jahr zu Jahr einvernehmlich festgelegt werden. Diese besagt, dass die Ziele zwischen den Parteien unter Berücksichtigung der Umsatzentwicklung in den vorangegangenen Monaten und mit einer gewissen Vorlaufzeit vor Ende des laufenden Jahres vereinbart werden. Für den Fall, dass keine Einigung über die neue Zielvorgabe zustande kommt, kann der Vertrag vorsehen, dass die Zielvorgabe des Vorjahres angewandt wird oder dass die Parteien das Recht haben, den Vertrag unter Einhaltung einer bestimmten Kündigungsfrist zu kündigen.

Andererseits kann die Zielvorgabe auch als Anreiz für den Vertriebshändler dienen: So kann z. B. vorgesehen werden, dass bei Erreichen eines bestimmten Umsatzes die Vereinbarung erneuert, die Gebietsexklusivität verlängert oder ein bestimmter kommerzieller Ausgleich für das folgende Jahr gewährt wird.

Eine letzte Empfehlung ist die korrekte Handhabung der Mindestzielklausel, sofern sie im Vertrag enthalten ist: Es kommt häufig vor, dass der Hersteller die Erreichung des Ziels für ein bestimmtes Jahr bestreitet, nachdem die Jahresziele über einen langen Zeitraum hinweg nicht erreicht oder nicht aktualisiert wurden, ohne dass dies irgendwelche Konsequenzen hatte.

In solchen Fällen ist es möglich, dass der Händler behauptet, dass ein impliziter Verzicht auf diesen vertraglichen Schutz vorliegt und der Widerruf daher nicht gültig ist: Um Streitigkeiten zu diesem Thema zu vermeiden, ist es ratsam, in der Mindestzielklausel ausdrücklich vorzusehen, dass die unterbliebene Anfechtung des Nichterreichens des Ziels während eines bestimmten Zeitraums nicht bedeutet, dass auf das Recht, die Klausel in Zukunft zu aktivieren, verzichtet wird.

Die Kündigungsfrist für die Beendigung eines internationalen Vertriebsvertrags

Der andere Streitpunkt zwischen den Parteien war die Verletzung eines Wettbewerbsverbots: Blue Ribbon verkaufte die Marke Nike , obwohl der Vertrag den Verkauf anderer in Japan hergestellter Schuhe untersagte.

Onitsuka Tiger behauptete, Blue Ribbon habe gegen das Wettbewerbsverbot verstoßen, während der Händler die Ansicht vertrat , dass er angesichts der bevorstehenden Entscheidung des Herstellers, die Vereinbarung zu kündigen, keine andere Wahl hatte.

Diese Art von Streitigkeiten kann vermieden werden, indem für die Beendigung (oder Nichtverlängerung) eine klare Kündigungsfrist festgelegt wird: Diese Frist hat die grundlegende Funktion, den Parteien die Möglichkeit zu geben, sich auf die Beendigung der Beziehung vorzubereiten und ihre Aktivitäten nach der Beendigung neu zu organisieren.

Um insbesondere Streitigkeiten wie die zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger zu vermeiden, kann in einem internationalen Vertriebsvertrag vorgesehen werden, dass die Parteien während der Kündigungsfristmit anderen potenziellen Vertriebshändlern und Herstellern in Kontakt treten können und dass dies nicht gegen die Ausschließlichkeits- und Wettbewerbsverpflichtungen verstößt.

Im Fall von Blue Ribbon war der Händler über die bloße Suche nach einem anderen Lieferanten hinaus sogar noch einen Schritt weiter gegangen, da er begonnen hatte, Nike-Produkte zu verkaufen, während der Vertrag mit Onitsuka noch gültig war. Dieses Verhalten stellt einen schweren Verstoß gegen die getroffene Ausschließlichkeitsvereinbarung dar.

Ein besonderer Aspekt, der bei der Kündigungsfrist zu berücksichtigen ist, ist die Dauer: Wie lang muss die Kündigungsfrist sein, um als fair zu gelten? Bei langjährigen Geschäftsbeziehungen ist es wichtig, der anderen Partei genügend Zeit einzuräumen, um sich auf dem Markt neu zu positionieren, nach alternativen Vertriebshändlern oder Lieferanten zu suchen oder (wie im Fall von Blue Ribbon/Nike) eine eigene Marke zu schaffen und einzuführen.

Ein weiteres Element, das bei der Mitteilung der Kündigung zu berücksichtigen ist, besteht darin, dass die Kündigungsfrist so bemessen sein muss, dass der Vertriebshändler die zur Erfüllung seiner Verpflichtungen während der Vertragslaufzeit getätigten Investitionen amortisieren kann; im Fall von Blue Ribbon hatte der Vertriebshändler auf ausdrücklichen Wunsch des Herstellers eine Reihe von Einmarkengeschäften sowohl an der West- als auch an der Ostküste der USA eröffnet.

Eine Kündigung des Vertrags kurz nach seiner Verlängerung und mit einer zu kurzen Vorankündigung hätte es dem Vertriebshändler nicht erlaubt, das Vertriebsnetz mit einem Ersatzprodukt neu zu organisieren, was die Schließung der Geschäfte, die die japanischen Schuhe bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt verkauft hatten, erzwungen hätte.

Im Allgemeinen ist es ratsam, eine Kündigungsfrist von mindestens 6 Monaten vorzusehen. Bei internationalen Vertriebsverträgen sollten jedoch neben den von den Parteien getätigten Investitionen auch etwaige spezifische Bestimmungen des auf den Vertrag anwendbaren Rechts (hier z. B. eine eingehende Analyse der plötzlichen Kündigung von Verträgen in Frankreich) oder die Rechtsprechung zum Thema Rücktritt von Geschäftsbeziehungen beachtet werden (in einigen Fällen kann die für einen langfristigen Vertriebskonzessionsvertrag als angemessen erachtete Frist 24 Monate betragen).

Schließlich ist es normal, dass der Händler zum Zeitpunkt des Vertragsabschlusses noch im Besitz von Produktvorräten ist: Dies kann problematisch sein, da der Händler in der Regel die Vorräte auflösen möchte (Blitzverkäufe oder Verkäufe über Internetkanäle mit starken Rabatten), was der Geschäftspolitik des Herstellers und der neuen Händler zuwiderlaufen kann.

Um diese Art von Situation zu vermeiden, kann in den Vertriebsvertrag eine Klausel aufgenommen werden, die das Recht des Herstellers auf Rückkauf der vorhandenen Bestände bei Vertragsende regelt, wobei der Rückkaufpreis bereits festgelegt ist (z. B. in Höhe des Verkaufspreises an den Händler für Produkte der laufenden Saison, mit einem Abschlag von 30 % für Produkte der vorangegangenen Saison und mit einem höheren Abschlag für Produkte, die mehr als 24 Monate zuvor verkauft wurden).

Markeninhaberschaft in einer internationalen Vertriebsvereinbarung

Im Laufe der Vertriebsbeziehung hatte Blue Ribbon eine neuartige Sohle für Laufschuhe entwickelt und die Marken Cortez und Boston für die Spitzenmodelle der Kollektion geprägt, die beim Publikum sehr erfolgreich waren und große Popularität erlangten: Bei Vertragsende beanspruchten nun beide Parteien das Eigentum an den Marken.

Derartige Situationen treten häufig in internationalen Vertriebsbeziehungen auf: Der Händler lässt die Marke des Herstellers in dem Land, in dem er tätig ist, registrieren, um Konkurrenten daran zu hindern, dies zu tun, und um die Marke im Falle des Verkaufs gefälschter Produkte schützen zu können; oder es kommt vor, dass der Händler, wie in dem hier behandelten Streitfall, an der Schaffung neuer, für seinen Markt bestimmter Marken mitwirkt.

Am Ende der Geschäftsbeeziehung, wenn keine klare Vereinbarung zwischen den Parteien vorliegt, kann es zu einem Streit wie im Fall Nike kommen: Wer ist der Eigentümer der Marke – der Hersteller oder der Händler?

Um Missverständnisse zu vermeiden, ist es ratsam, die Marke in allen Ländern zu registrieren, in denen die Produkte vertrieben werden, und nicht nur dort: Im Falle Chinas zum Beispiel ist es ratsam, die Marke auch dann zu registrieren, wenn sie dort nicht vertreiben wird, um zu verhindern, dass Dritte die Marke in böser Absicht übernehmen (weitere Informationen finden Sie in diesem Beitrag auf Legalmondo).

Es ist auch ratsam, in den Vertriebsvertrag eine Klausel aufzunehmen, die dem Händler die Eintragung der Marke (oder ähnlicher Marken) in dem Land, in dem er tätig ist, untersagt und dem Hersteller ausdrücklich das Recht einräumt, die Übertragung der Marke zu verlangen, falls dies dennoch geschieht.

Eine solche Klausel hätte die Entstehung des Rechtsstreits zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger verhindert.

Der von uns geschilderte Sachverhalt stammt aus dem Jahr 1976: Heutzutage ist es ratsam, im Vertrag nicht nur die Eigentumsverhältnisse an der Marke und die Art und Weise der Nutzung durch den Händler und sein Vertriebsnetz zu klären, sondern auch die Nutzung der Marke wie auch der Unterscheidungszeichen des Herstellers in den Kommunikationskanälen, insbesondere in den sozialen Medien, zu regeln.

Es ist ratsam, eindeutig festzulegen, dass niemand anderes als der Hersteller Eigentümer der Social-Media-Profile wie auch der erstellten Inhalte und der Daten ist, die durch die Verkaufs-, Marketing- und Kommunikationsaktivitäten in dem Land, in dem der Händler tätig ist, generiert werden, und dass er nur die Lizenz hat, diese gemäß den Anweisungen des Eigentümers zu nutzen.

Darüber hinaus ist es sinnvoll, in der Vereinbarung festzulegen, wie die Marke verwendet wird und welche Kommunikations- und Verkaufsförderungsmaßnahmen auf dem Markt ergriffen werden, um Initiativen zu vermeiden, die negative oder kontraproduktive Auswirkungen haben könnten.

Die Klausel kann auch durch die Festlegung von Vertragsstrafen für den Fall verstärkt werden, dass sich der Händler bei Vertragsende weigert, die Kontrolle über die digitalen Kanäle und die im Rahmen der Geschäftstätigkeit erzeugten Daten zu übertragen.

Mediation in internationalen Handelsverträgen

Ein weiterer interessanter Punkt, der sich am Fall Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger erläutern lässt , steht im Zusammenhang mit der Bewältigung von Konflikten in internationalen Vertriebsbeziehungen: Situationen wie die, die wir gesehen haben, können durch den Einsatz von Mediation effektiv gelöst werden.

Dabei handelt es sich um einen Schlichtungsversuch, mit dem ein spezialisiertes Gremium oder ein Mediator betraut wird, um eine gütliche Einigung zu erzielen und ein Gerichtsverfahren zu vermeiden.

Die Mediation kann im Vertrag als erster Schritt vor einem eventuellen Gerichts- oder Schiedsverfahren vorgesehen sein oder sie kann freiwillig im Rahmen eines bereits laufenden Gerichts- oder Schiedsverfahrens eingeleitet werden.

Die Vorteile sind vielfältig: Der wichtigste ist die Möglichkeit, eine wirtschaftliche Lösung zu finden, die die Fortsetzung der Beziehung ermöglicht, anstatt nur nach Wegen zur Beendigung der Geschäftsbeziehung zwischen den Parteien zu suchen.

Ein weiterer interessanter Aspekt der Mediation ist die Überwindung von persönlichen Konflikten: Im Fall Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka zum Beispiel war ein entscheidendes Element für die Eskalation der Probleme zwischen den Parteien die schwierige persönliche Beziehung zwischen dem CEO von Blue Ribbon und dem Exportmanager des japanischen Herstellers, die durch starke kulturelle Unterschiede verschärft wurde.

Der Mediationsprozess führt eine dritte Person ein, die in der Lage ist, einen Dialog mit den Parteien zu führen und sie bei der Suche nach Lösungen von gegenseitigem Interesse zu unterstützen, was entscheidend sein kann, um Kommunikationsprobleme oder persönliche Feindseligkeiten zu überwinden.

Für alle, die sich für dieses Thema interessieren, verweisen wir auf den hierzu verfassten Beitrag auf Legalmondo sowie auf die Aufzeichnung eines kürzlich durchgeführten Webinars zur Mediation internationaler Konflikte.

Streitbeilegungsklauseln in internationalen Vertriebsvereinbarungen

Der Streit zwischen Blue Ribbon und Onitsuka Tiger führte dazu, dass die Parteien zwei parallele Gerichtsverfahren einleiteten, eines in den USA (durch den Händler) und eines in Japan (durch den Hersteller).

Dies war nur deshalb möglich, weil der Vertrag nicht ausdrücklich vorsah, wie etwaige künftige Streitigkeiten beigelegt werden sollten. In der Konsequenz führte dies zu einer prozessual sehr komplizierten Situation mit gleich zwei gerichtlichen Fronten in verschiedenen Ländern.

Die Klauseln, die festlegen, welches Recht auf einen Vertrag anwendbar ist und wie Streitigkeiten beigelegt werden, werden in der Praxis als „Mitternachtsklauseln“ bezeichnet, da sie oft die letzten Klauseln im Vertrag sind, die spät in der Nacht ausgehandelt werden.

Es handelt sich hierbei um sehr wichtige Klauseln, die bewusst gewählt werden müssen, um unwirksame oder kontraproduktive Lösungen zu vermeiden.

Wie wir Ihnen helfen können

Der Abschluss eines internationalen Handelsvertriebsvertrags ist eine wichtige Investition, denn er regelt die vertragliche Beziehungen zwischen den Parteien verbindlich für die Zukunft und gibt ihnen die Instrumente an die Hand, um alle Situationen zu bewältigen, die sich aus der künftigen Zusammenarbeit ergeben werden.

Es ist nicht nur wichtig, eine korrekte, vollständige und ausgewogene Vereinbarung auszuhandeln und abzuschließen, sondern auch zu wissen, wie sie im Laufe der Jahre zu handhaben ist, vor allem, wenn Konfliktsituationen auftreten.

Legalmondo bietet Ihnen die Möglichkeit, mit Anwälten zusammenzuarbeiten, die in mehr als 60 Ländern Erfahrung im internationalen Handelsvertrieb haben: Bei bestehendem Beratungsbedarf schreiben Sie uns.

Nach italienischem Recht steht es den Vertragsparteien – die beide juristische Personen des Privatrechts sind – im Allgemeinen frei, das zuständige Gericht für Streitigkeiten aus einem solchen Vertrag zu vereinbaren.

Obwohl solche Klauseln gültig sind, kann ihre Durchsetzbarkeit durch bestimmte formale Anforderungen eingeschränkt werden, die berücksichtigt werden sollten.

Seltsamerweise sind diese Anforderungen oft strenger, wenn beide Parteien in Italien ansässig sind, und lockerer, wenn eine der Parteien im Ausland, insbesondere in einem anderen EU-Land, ansässig ist.

In Anbetracht der derzeitigen Unsicherheiten in der Rechtsprechung ist jedoch in jedem Fall ein vorsichtiges Vorgehen bei der Vertragsgestaltung gerechtfertigt.

Exklusives oder nicht exklusives Forum?

Nehmen wir zum Beispiel die folgende Klausel in einem Handelsvertrag zwischen zwei Privatunternehmen: „Zuständiges Gericht – Für alle Streitigkeiten sind die Gerichte von Mailand zuständig„.

Diese Klausel ist offensichtlich unbedenklich. Sie wurde jedoch vor kurzem vom italienischen Obersten Gerichtshof („Corte di Cassazione“) für nicht durchsetzbar erklärt, insbesondere unter dem Gesichtspunkt der Nichtexklusivität (Oberster Gerichtshof, Zivilabteilung (Cass. Civ. Sez.) VI-3, Beschluss vom 25.1.2018, Nr. 1838).

In diesem Fall ließ ein italienisches Unternehmen die andere Partei (ein anderes italienisches Unternehmen) seine allgemeinen Vertragsbedingungen unterzeichnen, die die oben genannte Klausel enthielten. Ungeachtet dessen wurde dem ersten Unternehmen ein Zahlungsbefehl („decreto ingiuntivo“) des Gerichts von Siena zugestellt, wo das zweite Unternehmen trotz der Zustimmung zur Gerichtsstandsklausel Klage erhoben hatte.

Das erste Unternehmen konnte sich nicht erfolgreich gegen den Zahlungsbefehl wehren, indem es das Argument der Unzuständigkeit des Gerichts von Siena anführte. Es konnte nämlich die in seinen allgemeinen Vertragsbedingungen enthaltene Gerichtsstandsklausel nicht durchsetzen, da in der Klausel nicht festgelegt war, dass die Gerichte von Mailand der „ausschließliche“ Gerichtsstand sind.

Nach Ansicht unseres Obersten Gerichtshofs (der damit seine eigene frühere Rechtsprechung bestätigte) hätte diese Klausel daher lauten müssen, damit sie wie gewünscht durchsetzbar ist: „Für alle Streitigkeiten sind ausschließlich die Gerichte von Mailand zuständig“.

Bemerkenswert ist jedoch, dass dieselben allgemeinen Vertragsbedingungen, wenn sie von einem Unternehmen mit Sitz in einem anderen EU-Land als Italien (z. B. Frankreich) unterzeichnet worden wären, das französische Unternehmen erfolgreich daran gehindert hätten, einen Rechtsstreit in Frankreich anzustrengen, selbst wenn die Gerichtsstandsklausel keine Ausschließlichkeitsbestimmung enthielt.

In Artikel 25 der Verordnung (EU) Nr. 1215/2012 heißt es nämlich ausdrücklich, dass die Gerichtsstandsklausel „ausschließlich gilt, sofern die Parteien nichts anderes vereinbart haben“.

Dies wurde auch vom Obersten Gerichtshof Italiens bestätigt (siehe z. B. die Entscheidung Nr. 3624 vom 8.3.2012).

Was geschieht nun, wenn der Vertragspartner des Mailänder Unternehmens ein Unternehmen mit Sitz in einem Nicht-EU-Land ist, das nicht durch internationale Verträge zu diesem Thema gebunden ist? Zum Beispiel ein US-amerikanisches Unternehmen?

Wäre die Klausel „Für alle Streitigkeiten sind die Gerichte von Mailand zuständig“ aus der Sicht eines italienischen Gerichts als ausschließlich anzusehen oder nicht?

Artikel 6 der Verordnung 1215/2012 sollte das italienische Gericht dazu veranlassen, diese Klausel gemäß Artikel 25 derselben Verordnung als ausschließlich auszulegen. In ähnlichen Fällen haben italienische Gerichte in der Vergangenheit solche Klauseln jedoch als nicht ausschließlich angesehen, indem sie die nationalen Vorschriften des internationalen Privatrechts (Art. 4 des Gesetzes 218/95) anwandten und sie im Einklang mit Artikel 29 Absatz 2 der Zivilprozessordnung auslegten (siehe z. B. Tribunale von Mailand, 11.12.1997). Folglich kann in dem oben beschriebenen Fall, wenn das US-Unternehmen trotz der oben genannten Klausel einen Prozess in seinem Land anstrengt, die in den USA erlassene Entscheidung in Italien anerkannt werden.

Das Haager Übereinkommen vom 30.6.2005 über Gerichtsstandsvereinbarungen sollte die obigen und andere Probleme lösen, da es (genau wie die europäische Verordnung) festlegt, dass der gewählte Gerichtsstand ausschließlich ist, sofern nicht ausdrücklich etwas anderes vereinbart wird. Allerdings ist dieses Übereinkommen derzeit nur in einer sehr begrenzten Anzahl von Ländern in Kraft (Europäische Union, Mexiko, Singapur).

Wenn man in einer solchen unsicheren Situation möchte, dass der gewählte Gerichtsstand unabhängig vom Sitz der anderen Partei ausschließlich gilt, ist es nach italienischem Recht sicherlich am klügsten, die Ausschließlichkeit in der Klausel festzulegen.

„Besondere Genehmigung“ missbräuchlicher Klauseln (Art. 1341 des Zivilgesetzbuchs)

Eine weitere Voraussetzung für die Durchsetzbarkeit von Gerichtsstandsklauseln nach italienischem Recht ist das Erfordernis einer „besonderen Genehmigung“ solcher Klauseln, wenn sie in allgemeinen Vertragsbedingungen enthalten sind. Gemäß Artikel 1341, zweiter Absatz, des Zivilgesetzbuches sind bestimmte Arten von „missbräuchlichen“ Klauseln in allgemeinen Vertragsbedingungen nicht durchsetzbar, wenn sie nicht schriftlich „besonders genehmigt“ wurden. Zu diesen „missbräuchlichen Klauseln“ gehören auch Schieds- und Gerichtsstandsklauseln, wenn sie für die Partei, die die allgemeinen Vertragsbedingungen verfasst hat, günstig sind.

Nach der ständigen Rechtsprechung unseres Obersten Gerichtshofs erfolgt eine solche „Sondergenehmigung“ in der Praxis durch eine zweite Unterschrift auf dem Vertrag, die eigenständig und getrennt von der Unterschrift sein muss, mit der der Vertrag normalerweise in seiner Gesamtheit genehmigt wird. Außerdem muss sich diese zweite Genehmigung ausdrücklich auf jede einzelne missbräuchliche Klausel beziehen, indem die Nummer und die Überschrift jeder dieser Klauseln angegeben werden.

Das besondere Genehmigungserfordernis für die Gerichtsstandsklauseln gilt jedoch nur für Verträge zwischen italienischen Parteien, nicht für internationale Verträge.

Insbesondere wenn die Verordnung (EU) Nr. 1215/2012 Anwendung findet, sind die weniger strengen Formvorschriften des Artikels Art. 25 auch dann einzuhalten, wenn die Gerichtsstandsklausel Teil der allgemeinen Vertragsbedingungen ist. In einem solchen Fall ist es erforderlich und ausreichend, dass der von den Parteien unterzeichnete Vertrag einen ausdrücklichen Verweis auf die allgemeinen Geschäftsbedingungen enthält, die die Gerichtsstandsklausel enthalten (siehe z. B. Cass. Sez. Un. 6.4.2017 n.8895). Bei allgemeinen Vertragsbedingungen in einem auf elektronischem Wege geschlossenen Kaufvertrag kann eine Gerichtsstandsklausel (ebenfalls gemäß der EU-Verordnung) durch einen „Klick“ wirksam akzeptiert werden (siehe EuGH-Urteil Nr. 322 vom 21.5.2015).

Selbst bei Anwendung der italienischen Vorschriften im internationalen Privatrecht (Art. 4, Gesetz 218/95) – d. h. im Wesentlichen in Angelegenheiten, an denen Parteien aus Nicht-EU-Staaten (oder Nicht-EWR/EFTA-Staaten) beteiligt sind – ist die Bedingung der „besonderen Genehmigung“ für Gerichtsstandsvereinbarungen nicht erforderlich, da ein solches Erfordernis in Artikel 4 nicht ausdrücklich vorgesehen ist, und zwar auch nicht im Wege der Auslegung (Verfassungsgericht 18/10/2000, Nr. 428).

Ungeachtet dessen ist jedoch noch nicht endgültig geklärt, ob das Erfordernis der „besonderen Genehmigung“ gemäß Artikel 1341 des Bürgerlichen Gesetzbuchs auch für internationale Verträge (wenn sie italienischem Recht unterliegen) als Voraussetzung für die Durchsetzung anderer Klauseln gelten soll, die in der Rechtsvorschrift als „missbräuchlich“ angesehen werden, wie z. B. Haftungsbeschränkungs- oder -ausschlussklauseln.

Daher ist es in Italien immer noch üblich, auch bei internationalen Verträgen allgemeine Vertragsklauseln zu formulieren, die eine zweite Unterschrift der Gegenpartei zur besonderen Genehmigung der mißbräuchlichen Klauseln vorsehen.

All dies in der Hoffnung, dass die italienische Rechtsprechung in Zukunft einen moderneren und internationaleren Ansatz entwickeln wird.

Summary

By means of Legislative Decree No. 198 of November 8th, 2021, Italy implemented Directive (EU) 2019/633 on unfair trading practices in business-to-business relationships in the agricultural and food supply chain. The Italian legislator introduced stricter rules than those provided for in the directive. Moreover, it has provided for some mandatory contractual requirements, within the framework of Article 168 of Regulation (EC) 1308/2013, but more restrictive than those of the Regulation. The new provisions shall apply irrespective of the law applicable to the contract and the country of the buyer, hence they concern cross-border relationships as well. They significantly impact contractual relationships related to the chain of fresh and processed food products, including wine, and certain non-food agricultural products, and require companies in the concerned sectors to review their contracts and business practices with respect to their relationships with customers and suppliers.

The provisions introduced by the decree also apply to existing contracts, which shall be made compliant by 15 June 2022.

Introduction

With Directive (EU) 2019/633, the EU legislator introduced a detailed set of unfair trading practices in business-to-business relationships in the agricultural and food supply chain, in order to tackle unbalanced trading practices imposed by strong contractual parties. The directive has been transposed in Italy by Legislative Decree No. 198 of November 8th, 2021 (it came into force on December 15th, 2021), which introduced a long list of provisions qualified as unfair trading practices in the context of business-to-business relationships in the agricultural and food supply chain. The list of unfair practices is broader than the one provided for in the EU directive.

The transposition of the directive was also the opportunity to introduce some mandatory requirements to contracts for the supply of goods falling within the scope of the decree. These requirements, adopted in the framework of Article 168 of Regulation (EC) 1308/2013, replaced and extended those provided for in Article 62 of Decree-Law 1/2012 and Article 10-quater of Decree-Law 27/2019.

Scope of application

The legislation applies to commercial relationships between buyers (including the public administration) and suppliers of agricultural and food products and in particular to B2B contracts having as object the transfer of such products.

It does not apply to agreements in which a consumer is party, to transfers with simultaneous payment and delivery of the goods and transfers of products to cooperatives or producer organisations within the meaning of Legislative Decree 102/2005.

It applies, inter alia, to sale, supply and distribution agreements.

Agricultural and food products means the goods listed in Annex I of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, as well as those not listed in that Annex but processed for use as food using listed products. This includes all products of the agri-food chain, fresh and processed, including wine, as well as certain agricultural products outside the food chain, including animal feed not intended for human consumption and floricultural products.

The rules apply to sales made by suppliers based in Italy, whilst the country where the buyer is based is not relevant. It applies irrespective of the law applicable to the relationship between the parties. Therefore, the new rules also apply in case of international contractual relationships subject to the law of another country.

In transposing the directive, the Italian legislator decided not to take into consideration the „size of the parties“: while the directive provides for turnover thresholds and applies to contractual relations in which the buyer has a turnover equal to or greater than the supplier, the Italian rules apply irrespective of the turnover of the parties.

Contractual requirements

Article 3 of the decree introduced some mandatory requirements for contracts for the supply or transfer of agricultural and food products. These requirements, adopted in the framework of Article 168 of Regulation (EC) 1308/2013, replaced and extended those established by Article 62 of Decree-Law 1/2012 and Article 10-quater of Decree-Law 27/2019 (which had been repealed).

Contracts must comply with the principles of transparency, fairness, proportionality and mutual consideration of performance.

Contracts must be in writing. Equivalent forms (transport documents, invoices and purchase orders) are only allowed if a framework agreement containing the essential terms of future supply agreements has been entered into between supplier and buyer.

Of great impact is the requirement for contracts to have a duration of at least 12 months (contracts with a shorter duration are automatically extended to the minimum duration). The legislator requires companies in the supply chain (with some exceptions) to operate not with individual purchases but with continuous supply agreements, which shall indicate the quantity and characteristics of the products, the price, the delivery and payment method.

A considerable operational change is required due to the need to plan and contract quantities and prices of supplies. As far as the price is concerned, it no longer seems possible to agree on it from time to time during the relationship on the basis of orders or new price lists from the supplier. The price may be fixed or determinable according to the criteria laid down in the contract. Therefore, companies not intending to operate at a fixed price will have to draft contractual clauses containing the criteria for determining the price (e.g. linking it to stock exchange quotations, fluctuations in raw material or energy prices).

The minimum duration of at least 12 months may be waived. However, the derogation shall be justified, either by the seasonality of the products or other reasons (that are not specified in the decree). Other reasons could include the need for the buyer to meet an unforeseen increase in demand, or the need to replace a lost supply.

The provisions described above may also be derogated from by framework agreements concluded by the most representative business organisations.

Prohibited unfair trading practices and specific derogations

The decree provides for several cases qualified as unfair trading practices, some of which are additional to those provided for in the directive.

Article 4 contains two categories of prohibited practices, which transpose those of the directive.

The first concerns practices which are always prohibited, including, first of all, payment of the price after 30 days for perishable products and after 60 days for non-perishable products. This category also includes the cancellation of orders for perishable goods at short notice; unilateral amendments to certain contractual terms; requests for payments not related to the sale; contractual clauses obliging the supplier to bear the cost of deterioration or loss of the goods after delivery; refusal by the buyer to confirm the contractual terms in writing; the acquisition, use and disclosure of the supplier’s trade secrets; the threat of commercial retaliation by the buyer against the supplier who intends to exercise contractual rights; and the claim by the buyer for the costs incurred in examining customer complaints relating to the sale of the supplier’s products.

The second category relates to practices which are prohibited unless provided for in a written agreement between the parties: these include the return of unsold products without payment for them or for their disposal; requests to the supplier for payments for stoking, displaying or listing the products or making them available on the market; requests to the supplier to bear the costs of discounts, advertising, marketing and personnel of the buyer to fitting-out premises used for the sale of the products.

Article 5 provides for further practices always prohibited, in addition to those of the directive, such as the use of double-drop tenders and auctions (“gare ed aste a doppio ribasso”); the imposition of contractual conditions that are excessively burdensome for the supplier; the omission from the contract of the terms and conditions set out in Article 168(4) of Regulation (EU) 1308/2013 (among which price, quantity, quality, duration of the agreement); the direct or indirect imposition of contractual conditions that are unjustifiably burdensome for one of the parties; the application of different conditions for equivalent services; the imposition of ancillary services or services not related to the sale of the products; the exclusion of default interest to the detriment of the creditor or of the costs of debt collection; clauses imposing on the supplier a minimum time limit after delivery in order to be able to issue the invoice; the imposition of the unjustified transfer of economic risk on one of the parties; the imposition of an excessively short expiry date by the supplier of products, the maintenance of a certain assortment of products, the inclusion of new products in the assortment and privileged positions of certain products on the buyer’s premises.

A specific discipline is provided for sales below cost: Article 7 establishes that, as regards fresh and perishable products, this practice is allowed only in case of unsold products at risk of perishing or in case of commercial operations planned and agreed with the supplier in writing, while in the event of violation of this provision the price established by the parties is replaced by law.

Sanctioning system and supervisory authorities

The provisions introduced by the decree, as regards both contractual requirements and unfair trading practices, are backed up by a comprehensive system of sanctions.

Contractual clauses or agreements contrary to mandatory contractual requirements, those that constitute unfair trading practices and those contrary to the regulation of sales below cost are null and void.

The decree provides for specific financial penalties (one for each case) calculated between a fixed minimum (which, depending on the case, may be from 1,000 to 30,000 euros) and a variable maximum (between 3 and 5%) linked to the turnover of the offender; there are also certain cases in which the penalty is further increased.

In any event, without prejudice to claims for damages.

Supervision of compliance with the provisions of the decree is entrusted to the Central Inspectorate for the Protection of Quality and Fraud Repression of Agri-Food Products (ICQRF), which may conduct investigations, carry out unannounced on-site inspections, ascertain violations, require the offender to put an end to the prohibited practices and initiate proceedings for the imposition of administrative fines, without prejudice to the powers of the Competition and Market Authority (AGCM).

Recommended activities

The provisions introduced by the decree also apply to existing contracts, which shall be made compliant by 15 June 2022. Therefore:

- the companies involved, both Italian and foreign, should carry out a review of their business practices, current contracts and general terms and conditions of supply and purchase, and then identify any gaps with respect to the new provisions and adopt the relevant corrective measures.

- As the new legislation applies irrespective of the applicable law and is EU-derived, it will be important for companies doing business abroad to understand how the EU directive has been implemented in the countries where they operate and verify the compliance of contracts with these rules as well.

Summary: Article 44 of Decree Law No. 76 of July 16, 2020 (the so-called „Simplifications Decree„) provides that, until June 30, 2021, capital increases by joint stock companies (società per azioni), limited partnerships by shares (società in accomandita per azioni) and limited liability companies (società a responsabilità limitata) may be approved with the favorable vote of the majority of the share capital represented at the shareholders‘ meeting, provided that at least half of the share capital is present, even if the bylaws establish higher majorities.

The rule has a significant impact on the position of minority shareholders (and investors) of unlisted Italian companies, the protection of which is frequently entrusted (also) to bylaws clauses establishing qualified majorities for the approval of capital increases.

After describing the new rule, some considerations will be made on the consequences and possible safeguards for minority shareholders, limited to unlisted companies.

Simplifications Decree: the reduction of majorities for the approval of capital increases in Italian joint stock companies, limited partnerships by shares and limited liability companies

Article 44 of Decree Law No. 76 of July 16, 2020 (the so-called ‚Simplifications Decree‚)[1] temporarily reduced, until 30.6.2021, the majorities for the approval by the extraordinary shareholders‘ meeting of certain resolutions to increase the share capital.

The rule applies to all companies, including listed ones. It applies to resolutions of the extraordinary shareholders‘ meeting on the following subjects:

- capital increases through contributions in cash, in kind or in receivables, pursuant to Articles 2439, 2440 and 2441 (regarding joint stock companies and limited partnerships by shares), and to Articles 2480, 2481 and 2481-bis of the Italian Civil Code (regarding limited liability companies);

- the attribution to the directors of the power to increase the share capital, pursuant to Article 2443 (regarding joint stock companies and limited partnerships by shares) and to Article 2480 of the Italian Civil Code (regarding limited liability companies).

The ordinary rules provide the following mayorities:

(a) for joint stock companies and limited partnerships by shares: (i) on first call a majority of more than half of the share capital (Art. 2368, second paragraph, Italian Civil Code); (ii) on second call a majority of two thirds of the share capital presented at the meeting (Art. 2369, third paragraph, Italian Civil Code);

(b) for limited liability companies, a majority of more than half of the share capital (Art. 2479-bis, third paragraph, Italian Civil Code);

(c) for listed companies, a majority of two thirds of the share capital represents-to in the shareholders‘ meeting (Art. 2368, second paragraph and Art. 2369, third paragraph, Italian Civil Code).

Most importantly, the ordinary rules allow for qualified majorities (i.e., higher than those required by law) in the bylaws.

The temporary provisions of Article 44 of the Simplifications Decree provide that resolutions are approved with the favourable vote of the majority of the share capital represented at the shareholders‘ meeting, provided that at least half of the share capital is present. This majority also applies if the bylaws provide for higher majorities.

Simplifications Decree: the impact of the decrease in majorities for the approval of capital increases on minority shareholders of unlisted Italian companies

The rule has a significant impact on the position of minority shareholders (and investors) in unlisted Italian companies. It can be strongly criticised, particularly because it allows derogations from the higher majorities established in the bylaws, thus affecting ongoing relationships and the governance agreed between shareholders and reflected in the bylaws.

Qualified majorities, higher than the legal ones, for the approval of capital increases are a fundamental protection for minority shareholders (and investors). They are frequently introduced in the bylaws: when the company is set up with several partners, in the context of aggregation transactions, in investment transactions, private equity and venture capital transactions.

Qualified majorities prevent majority shareholders from carrying out transactions without the consent of minority shareholders (or some of them), which have a significant impact on the company and the position of minority shareholders. In fact, capital increases through contributions of assets reduce the minority shareholder’s shareholding percentage and can significantly change the company’s business (e.g. through the contribution of a business). Capital increases in cash force the minority shareholder to choose between further investing in the company or reducing its shareholding.

The reduction in the percentage of participation may imply the loss of important protections, linked to the possession of a participation above a certain threshold. These are not only certain rights provided for by law in favour of minority shareholders[2], but – with even more serious effects – the protections deriving from the qualified majorities provided for in the bylaws to approve certain decisions. The most striking case is that of the qualified majority for resolutions amending the bylaws, so that the amendments cannot be approved without the consent of the minority shareholders (or some of them). This is a fundamental clause, in order to ensure stability for certain provisions of the bylaws, agreed between the shareholders, that protect the minority shareholders, such as: pre-emption and tag-along rights, list voting for the appointment of the board of directors, qualified majorities for the taking of decisions by the shareholders‘ meeting or the board of directors, limits on the powers that can be delegated by the board of directors. Through the capital increase, the majority can obtain a percentage of the shareholding that allows it to amend the bylaws, unilaterally departing from the governance structure agreed with the other shareholders.

The legislator has disregarded all this and has introduced a rule that does not simplify. Rather, it fuels conflicts between the shareholders and undermines legal certainty, thus discouraging investments rather than encouraging them.

Simplifications Decree: checks and safeguards for minority shareholders with respect to the decrease in majorities for the approval of capital increases

In order to assess the situation and the protection of the minority shareholder it is necessary to examine any shareholders‘ agreement in force between the shareholders. The existence of a shareholders‘ agreement will be almost certain in private equity or venture capital transactions or by other professional investors. But outside of these cases there are many companies, especially among small and medium-sized enterprises, where the relationships between the shareholders are governed exclusively by the bylaws.

In the shareholders‘ agreement it will have to be verified whether there are clauses binding the shareholders, as parties to the agreement, to approve capital increases by qualified majority, i.e. higher than those required by law. Or whether the agreement make reference to a text of the bylaws (attached or by specific reference) that provides for such a majority, so that compliance with the qualified majority can be considered as an obligation of the parties to the shareholders‘ agreement.

In this case, the shareholders‘ agreement will protect the minority shareholder(s), as Article 44 of the Simplifications Decree does not introduce an exception to the clauses of the shareholders‘ agreement.

The protection offered by the shareholders‘ agreement is strong, but lower than that of the bylaws. The clause in the bylaws requiring a qualified majority binds all shareholders and the company, so the capital increase cannot be validly approved in violation of the bylaws. The shareholders‘ agreement, on the other hand, is only binding between the parties to the agreement, so it does not prevent the company from approving the capital increase, even if the shareholder’s vote violates the obligations of the shareholders‘ agreement. In this case, the other shareholders will be entitled to compensation for the damage suffered as a result of the breach of the agreement.

In the absence of a shareholders‘ agreement that binds the shareholders to respect a qualified majority for the approval of the capital increase, the minority shareholder has only the possibility of challenging the resolution to increase the capital, due to abuse of the majority, if the resolution is not justified in the interest of the company and the majority shareholder’s vote pursues a personal interest that is antithetical to the company’s interest, or if it is the instrument of fraudulent activity by the majority shareholders aimed at infringing the rights of minority shareholders[3]. A narrow escape, and a protection certainly insufficient.

[1] The Simplifications Decree was converted into law by Law no. 120 of September 11, 2020. The conversion law replaced art. 44 of the Simplifications Decree, extending the temporary discipline provided therein to capital increases in cash and to capital increases of limited liability companies.

[2] For example: the percentage of 10% (33% for limited liability companies) for the right of shareholders to obtain the call of the meeting (art. 2367; art. 2479 Italian Civil Code); the percentage of 20% (10% for limited liability companies) to prevent the waiver or settlement of the liability action against the directors (art. 2393, sixth paragraph; art. 2476, fifth paragraph, Italian Civil Code); the percentage of 20% for the exercise by the shareholder of the liability action against the directors (art. 2393-bis, Civil Code).

[3] Cass. Civ., 12 December 2005, no. 27387; Trib. Roma, 31 March 2017, no. 6452.

In 2019 the Private Equity and Venture Capital players have invested Euro 7,223 million in 370 transactions in the Italian Market, 26% less than 2018; these are the outcomes released on March 24th by AIFI (Italian Association of Private Equity, Venture Capital e Private Debt).

In this slowing down scenario the spreading of Covid-19 is impacting Private Equity and Venture Capital transactions currently in progress, thus raising implications and alerts that will considerably affect both further capital investments and the legal approach to investments themselves.

Companies spanning a wide range of industries are concerned by Covid-19 health emergency, with diverse impacts on businesses depending on the industry. In this scenario, product companies, direct-to-consumer companies, and retail-oriented businesses appear to be more affected than service, digital, and hi-tech companies. Firms and investors will both need to batten down the hatches, as to minimize the effects of the economic contraction on the on-going investment transactions. In this scenario, investors hypothetically backing off from funding processes represent an issue of paramount concern for start-ups, as these companies are targeted by for VC and PE investments. In that event, the extent of the risk would be dependent upon the investment agreements and share purchase agreements (SPAs) entered into and the term sheets approved by the parties.

MAC/MAE clauses

The right of investors to withdrawal (way out) from a transaction is generally secured by the so-called MAC or MAE clauses – respectively, material adverse change clause or material adverse effect. These clauses, as the case may be and in the event of unforeseeable circumstances, upon the subscription of the agreements, which significantly impact the business or particular variables of the investment, allow investors to decide not to proceed to closing, not to proceed to the subscription and the payment of the share capital increase, when previously resolved, to modify/renegotiate the enterprise value, or to split the proposed investment/acquisition into multiple tranches.

These estimates, in terms of type and potential methods of application of the clauses, usually depend on a number of factors, including the governing law for the agreements – if other than Italian – with this circumstance possibly applying in the case of foreign investors imposing the existing law in their jurisdiction, as the result of their position in the negotiation.

When the enforcement of MAC/MAE clauses leads to the modification/renegotiation of the enterprise value – that is to be lowered – it is advisable to provide for specific contract terms covering calculating mechanisms allowing for smoothly redefining the start-up valuation in the venture capital deals, with the purpose of avoiding any gridlocks that would require further involvement of experts or arbitrators.

In the absence of MAC/MAE clauses and in the case of agreements governed by the Italian law, the Civil Code provides for a contractual clause called ‘supervenient burdensomeness’ (eccessiva onerosità sopravvenuta) of a specific performance (i.e. the investment), with the consequent right for the party whose performance has become excessively burdensome to terminate the contract or to make changes to the contract, with a view to fair and balanced conditions – this solution however implies an inherent degree of complexity and cannot be instantly implemented. In case of agreements governed by foreign laws, it shall be checked whether or not the applicable provisions allow the investor to exit the transaction.

Interim Period clauses

MAC/MAE are generally negotiated when the time expected to closing is medium or long. Similarly, time factors underpin the concept of the Interim Period clauses regulating the business operation in the period between signing and closing, by re-shaping the company’s ordinary scope of business, i.e. introducing maximum expenditure thresholds and providing for the prohibition to execute a variety of transactions, such as capital-related transactions, except when the investors, which shall be entitled to remove these restrictions from time to time, agree otherwise.

It is recommended to ascertain that the Interim Period clauses provide for a possibility to derogate from these restrictions, following prior authorization from the investors, and that said clauses do not require, where this possibility is lacking, for an explicit modification to the provision because of the occurrence of any operational need due to the Covid-19 emergency.

Conditions for closing

The Government actions providing for measures to contain coronavirus have caused several slowdowns that may impact on the facts or events that are considered as preliminary conditions which, when occurring, allow to proceed to closing. Types of such conditions range from authorisations to public entities (i.e. IPs jointly owned with a university), to the achievement of turnover objectives or the completion of precise milestones, that may be negatively affected by the present standstill of companies and bodies. Where these conditions were in fact jeopardised by the events triggered by the Covid-19 outbreak, this would pose important challenges to closing, except where expressly provided that the investor can renounce, with consent to proceed to the investment in all cases. This is without prejudice to the possibility of renegotiating the conditions, in agreement with all the parties.

Future investments: best practice

Covid-19 virus related emergency calls for a change in the best practice of Private Equity and Venture Capital transactions: these should carry out detailed Due diligences on aspects which so far have been under-examined.

This is particularly true for insurance policies covering cases of business interruption resulting from extraordinary and unpredictable events; health insurance plans for employees; risk management procedures in supply chain contracts, especially with foreign counterparts; procedures for smart working and relevant GDPR compliance issues in case of targeted companies based in EU and UK; contingency plans, workplace safety, also in connection with the protocols that ensure ad-hoc policies for in-house work.

Investment protection should therefore also involve MAC/MAE clauses and relevant price adjustment mechanisms, including for the negotiation of contract-related warranties (representation & warranties). A special focus shall be given now, with a different approach, to the companies’ ability to tackle and minimize the risks that may arise from unpredictable events of the same scope as Covid-19, which is now affecting privacy systems, the workforce, the management of supply chain contracts, and the creditworthiness of financing agreements.

This emergency will lead investors to value the investments with even greater attention to information, other than financial ones, about targeted companies.