-

Italia

International distribution agreements | 7 lessons from the history of Nike

25 febrero 2023

- Contratos

- Contratos de distribución

- Propiedad Industrial e Intelectual

- Patentes y Marcas

Summary

Phil Knight, the founder of Nike, imported the Japanese brand Onitsuka Tiger into the US market in 1964 and quickly gained a 70% share. When Knight learned Onitsuka was looking for another distributor, he created the Nike brand. This led to two lawsuits between the two companies, but Nike eventually won and became the most successful sportswear brand in the world. This article looks at the lessons to be learned from the dispute, such as how to negotiate an international distribution agreement, contractual exclusivity, minimum turnover clauses, duration of the contract, ownership of trademarks, dispute resolution clauses, and more.

What I talk about in this article

- The Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger dispute and the birth of Nike

- How to negotiate an international distribution agreement

- Contractual exclusivity in a commercial distribution agreement

- Minimum Turnover clauses in distribution contracts

- Duration of the contract and the notice period for termination

- Ownership of trademarks in commercial distribution contracts

- The importance of mediation in international commercial distribution agreements

- Dispute resolution clauses in international contracts

- How we can help you

The Blue Ribbon vs Onitsuka Tiger dispute and the birth of Nike

Why is the most famous sportswear brand in the world Nike and not Onitsuka Tiger?

Shoe Dog is the biography of the creator of Nike, Phil Knight: for lovers of the genre, but not only, the book is really very good and I recommend reading it.

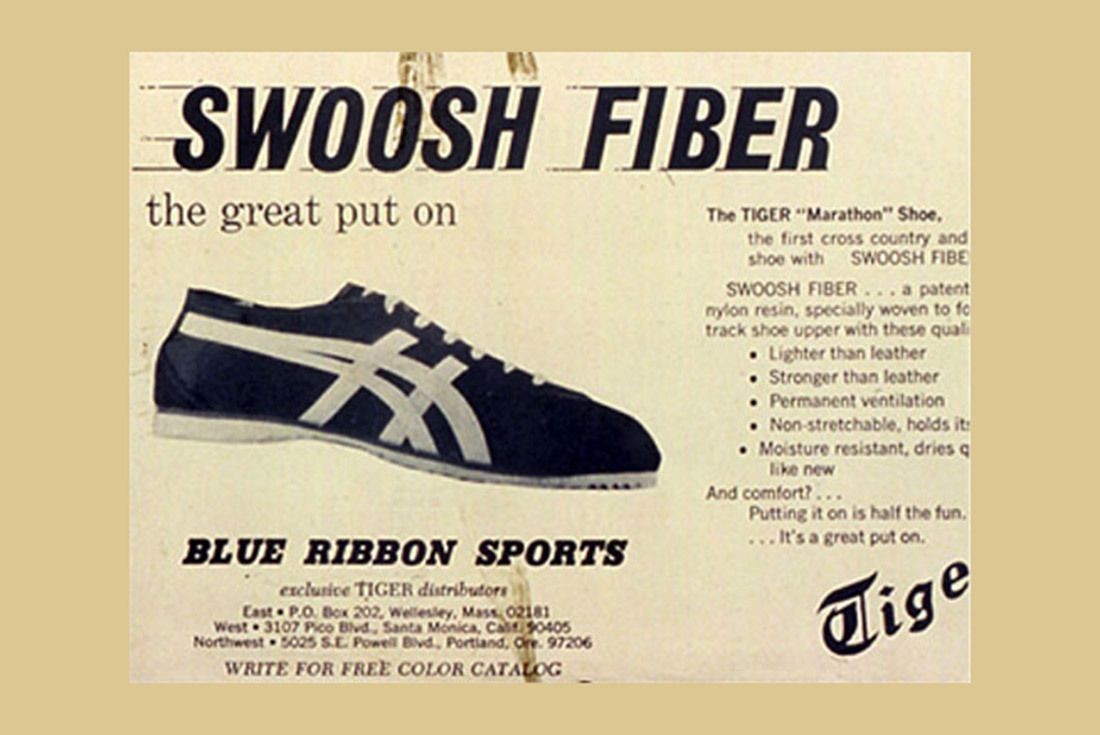

Moved by his passion for running and intuition that there was a space in the American athletic shoe market, at the time dominated by Adidas, Knight was the first, in 1964, to import into the U.S. a brand of Japanese athletic shoes, Onitsuka Tiger, coming to conquer in 6 years a 70% share of the market.

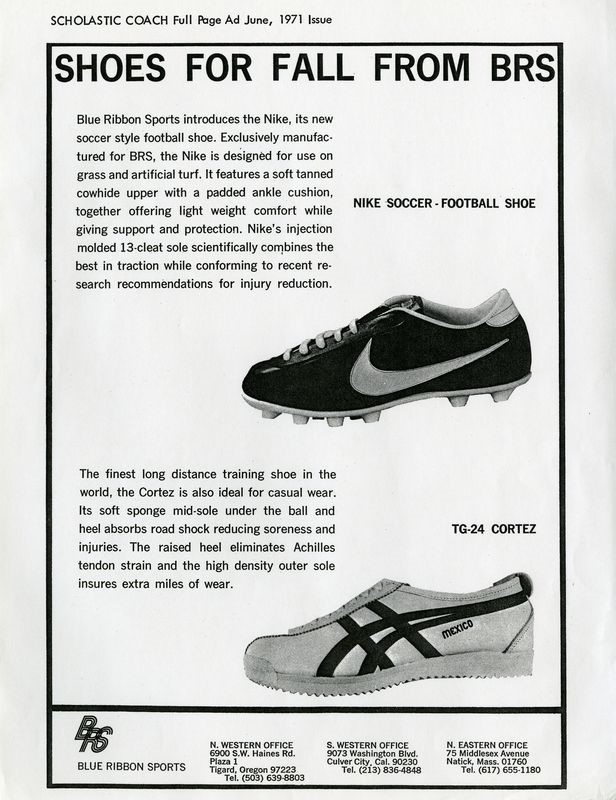

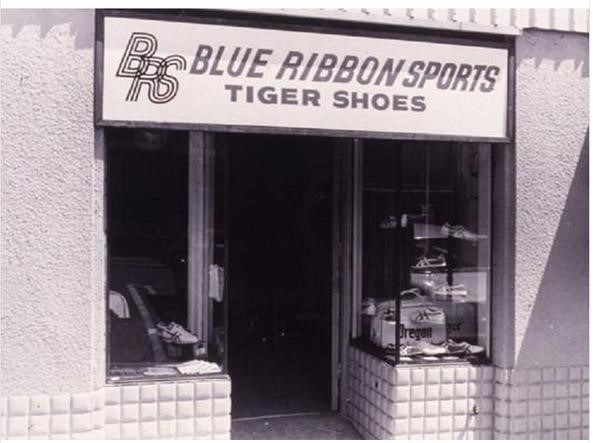

The company founded by Knight and his former college track coach, Bill Bowerman, was called Blue Ribbon Sports.

The business relationship between Blue Ribbon-Nike and the Japanese manufacturer Onitsuka Tiger was, from the beginning, very turbulent, despite the fact that sales of the shoes in the U.S. were going very well and the prospects for growth were positive.

When, shortly after having renewed the contract with the Japanese manufacturer, Knight learned that Onitsuka was looking for another distributor in the U.S., fearing to be cut out of the market, he decided to look for another supplier in Japan and create his own brand, Nike.

Upon learning of the Nike project, the Japanese manufacturer challenged Blue Ribbon for violation of the non-competition agreement, which prohibited the distributor from importing other products manufactured in Japan, declaring the immediate termination of the agreement.

In turn, Blue Ribbon argued that the breach would be Onitsuka Tiger’s, which had started meeting other potential distributors when the contract was still in force and the business was very positive.

This resulted in two lawsuits, one in Japan and one in the U.S., which could have put a premature end to Nike’s history.

Fortunately (for Nike) the American judge ruled in favor of the distributor and the dispute was closed with a settlement: Nike thus began the journey that would lead it 15 years later to become the most important sporting goods brand in the world.

Let’s see what Nike’s history teaches us and what mistakes should be avoided in an international distribution contract.

How to negotiate an international commercial distribution agreement

In his biography, Knight writes that he soon regretted tying the future of his company to a hastily written, few-line commercial agreement at the end of a meeting to negotiate the renewal of the distribution contract.

What did this agreement contain?

The agreement only provided for the renewal of Blue Ribbon’s right to distribute products exclusively in the USA for another three years.

It often happens that international distribution contracts are entrusted to verbal agreements or very simple contracts of short duration: the explanation that is usually given is that in this way it is possible to test the commercial relationship, without binding too much to the counterpart.

This way of doing business, though, is wrong and dangerous: the contract should not be seen as a burden or a constraint, but as a guarantee of the rights of both parties. Not concluding a written contract, or doing so in a very hasty way, means leaving without clear agreements fundamental elements of the future relationship, such as those that led to the dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger: commercial targets, investments, ownership of brands.

If the contract is also international, the need to draw up a complete and balanced agreement is even stronger, given that in the absence of agreements between the parties, or as a supplement to these agreements, a law with which one of the parties is unfamiliar is applied, which is generally the law of the country where the distributor is based.

Even if you are not in the Blue Ribbon situation, where it was an agreement on which the very existence of the company depended, international contracts should be discussed and negotiated with the help of an expert lawyer who knows the law applicable to the agreement and can help the entrepreneur to identify and negotiate the important clauses of the contract.

Territorial exclusivity, commercial objectives and minimum turnover targets

The first reason for conflict between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger was the evaluation of sales trends in the US market.

Onitsuka argued that the turnover was lower than the potential of the U.S. market, while according to Blue Ribbon the sales trend was very positive, since up to that moment it had doubled every year the turnover, conquering an important share of the market sector.

When Blue Ribbon learned that Onituska was evaluating other candidates for the distribution of its products in the USA and fearing to be soon out of the market, Blue Ribbon prepared the Nike brand as Plan B: when this was discovered by the Japanese manufacturer, the situation precipitated and led to a legal dispute between the parties.

The dispute could perhaps have been avoided if the parties had agreed upon commercial targets and the contract had included a fairly standard clause in exclusive distribution agreements, i.e. a minimum sales target on the part of the distributor.

In an exclusive distribution agreement, the manufacturer grants the distributor strong territorial protection against the investments the distributor makes to develop the assigned market.

In order to balance the concession of exclusivity, it is normal for the producer to ask the distributor for the so-called Guaranteed Minimum Turnover or Minimum Target, which must be reached by the distributor every year in order to maintain the privileged status granted to him.

If the Minimum Target is not reached, the contract generally provides that the manufacturer has the right to withdraw from the contract (in the case of an open-ended agreement) or not to renew the agreement (if the contract is for a fixed term) or to revoke or restrict the territorial exclusivity.

In the contract between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger, the agreement did not foresee any targets (and in fact the parties disagreed when evaluating the distributor’s results) and had just been renewed for three years: how can minimum turnover targets be foreseen in a multi-year contract?

In the absence of reliable data, the parties often rely on predetermined percentage increase mechanisms: +10% the second year, + 30% the third, + 50% the fourth, and so on.

The problem with this automatism is that the targets are agreed without having available the real data on the future trend of product sales, competitors’ sales and the market in general, and can therefore be very distant from the distributor’s current sales possibilities.

For example, challenging the distributor for not meeting the second or third year’s target in a recessionary economy would certainly be a questionable decision and a likely source of disagreement.

It would be better to have a clause for consensually setting targets from year to year, stipulating that targets will be agreed between the parties in the light of sales performance in the preceding months, with some advance notice before the end of the current year. In the event of failure to agree on the new target, the contract may provide for the previous year’s target to be applied, or for the parties to have the right to withdraw, subject to a certain period of notice.

It should be remembered, on the other hand, that the target can also be used as an incentive for the distributor: it can be provided, for example, that if a certain turnover is achieved, this will enable the agreement to be renewed, or territorial exclusivity to be extended, or certain commercial compensation to be obtained for the following year.

A final recommendation is to correctly manage the minimum target clause, if present in the contract: it often happens that the manufacturer disputes the failure to reach the target for a certain year, after a long period in which the annual targets had not been reached, or had not been updated, without any consequences.

In such cases, it is possible that the distributor claims that there has been an implicit waiver of this contractual protection and therefore that the withdrawal is not valid: to avoid disputes on this subject, it is advisable to expressly provide in the Minimum Target clause that the failure to challenge the failure to reach the target for a certain period does not mean that the right to activate the clause in the future is waived.

The notice period for terminating an international distribution contract

The other dispute between the parties was the violation of a non-compete agreement: the sale of the Nike brand by Blue Ribbon, when the contract prohibited the sale of other shoes manufactured in Japan.

Onitsuka Tiger claimed that Blue Ribbon had breached the non-compete agreement, while the distributor believed it had no other option, given the manufacturer’s imminent decision to terminate the agreement.

This type of dispute can be avoided by clearly setting a notice period for termination (or non-renewal): this period has the fundamental function of allowing the parties to prepare for the termination of the relationship and to organize their activities after the termination.

In particular, in order to avoid misunderstandings such as the one that arose between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger, it can be foreseen that during this period the parties will be able to make contact with other potential distributors and producers, and that this does not violate the obligations of exclusivity and non-competition.

In the case of Blue Ribbon, in fact, the distributor had gone a step beyond the mere search for another supplier, since it had started to sell Nike products while the contract with Onitsuka was still valid: this behavior represents a serious breach of an exclusivity agreement.

A particular aspect to consider regarding the notice period is the duration: how long does the notice period have to be to be considered fair? In the case of long-standing business relationships, it is important to give the other party sufficient time to reposition themselves in the marketplace, looking for alternative distributors or suppliers, or (as in the case of Blue Ribbon/Nike) to create and launch their own brand.

The other element to be taken into account, when communicating the termination, is that the notice must be such as to allow the distributor to amortize the investments made to meet its obligations during the contract; in the case of Blue Ribbon, the distributor, at the express request of the manufacturer, had opened a series of mono-brand stores both on the West and East Coast of the U.S.A..

A closure of the contract shortly after its renewal and with too short a notice would not have allowed the distributor to reorganize the sales network with a replacement product, forcing the closure of the stores that had sold the Japanese shoes up to that moment.

Generally, it is advisable to provide for a notice period for withdrawal of at least 6 months, but in international distribution contracts, attention should be paid, in addition to the investments made by the parties, to any specific provisions of the law applicable to the contract (here, for example, an in-depth analysis for sudden termination of contracts in France) or to case law on the subject of withdrawal from commercial relations (in some cases, the term considered appropriate for a long-term sales concession contract can reach 24 months).

Finally, it is normal that at the time of closing the contract, the distributor is still in possession of stocks of products: this can be problematic, for example because the distributor usually wishes to liquidate the stock (flash sales or sales through web channels with strong discounts) and this can go against the commercial policies of the manufacturer and new distributors.

In order to avoid this type of situation, a clause that can be included in the distribution contract is that relating to the producer’s right to repurchase existing stock at the end of the contract, already setting the repurchase price (for example, equal to the sale price to the distributor for products of the current season, with a 30% discount for products of the previous season and with a higher discount for products sold more than 24 months previously).

Trademark Ownership in an International Distribution Agreement

During the course of the distribution relationship, Blue Ribbon had created a new type of sole for running shoes and coined the trademarks Cortez and Boston for the top models of the collection, which had been very successful among the public, gaining great popularity: at the end of the contract, both parties claimed ownership of the trademarks.

Situations of this kind frequently occur in international distribution relationships: the distributor registers the manufacturer’s trademark in the country in which it operates, in order to prevent competitors from doing so and to be able to protect the trademark in the case of the sale of counterfeit products; or it happens that the distributor, as in the dispute we are discussing, collaborates in the creation of new trademarks intended for its market.

At the end of the relationship, in the absence of a clear agreement between the parties, a dispute can arise like the one in the Nike case: who is the owner, producer or distributor?

In order to avoid misunderstandings, the first advice is to register the trademark in all the countries in which the products are distributed, and not only: in the case of China, for example, it is advisable to register it anyway, in order to prevent third parties in bad faith from taking the trademark (for further information see this post on Legalmondo).

It is also advisable to include in the distribution contract a clause prohibiting the distributor from registering the trademark (or similar trademarks) in the country in which it operates, with express provision for the manufacturer’s right to ask for its transfer should this occur.

Such a clause would have prevented the dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger from arising.

The facts we are recounting are dated 1976: today, in addition to clarifying the ownership of the trademark and the methods of use by the distributor and its sales network, it is advisable that the contract also regulates the use of the trademark and the distinctive signs of the manufacturer on communication channels, in particular social media.

It is advisable to clearly stipulate that the manufacturer is the owner of the social media profiles, of the content that is created, and of the data generated by the sales, marketing and communication activity in the country in which the distributor operates, who only has the license to use them, in accordance with the owner’s instructions.

In addition, it is a good idea for the agreement to establish how the brand will be used and the communication and sales promotion policies in the market, to avoid initiatives that may have negative or counterproductive effects.

The clause can also be reinforced with the provision of contractual penalties in the event that, at the end of the agreement, the distributor refuses to transfer control of the digital channels and data generated in the course of business.

Mediation in international commercial distribution contracts

Another interesting point offered by the Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger case is linked to the management of conflicts in international distribution relationships: situations such as the one we have seen can be effectively resolved through the use of mediation.

This is an attempt to reconcile the dispute, entrusted to a specialized body or mediator, with the aim of finding an amicable agreement that avoids judicial action.

Mediation can be provided for in the contract as a first step, before the eventual lawsuit or arbitration, or it can be initiated voluntarily within a judicial or arbitration procedure already in progress.

The advantages are many: the main one is the possibility to find a commercial solution that allows the continuation of the relationship, instead of just looking for ways for the termination of the commercial relationship between the parties.

Another interesting aspect of mediation is that of overcoming personal conflicts: in the case of Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka, for example, a decisive element in the escalation of problems between the parties was the difficult personal relationship between the CEO of Blue Ribbon and the Export manager of the Japanese manufacturer, aggravated by strong cultural differences.

The process of mediation introduces a third figure, able to dialogue with the parts and to guide them to look for solutions of mutual interest, that can be decisive to overcome the communication problems or the personal hostilities.

For those interested in the topic, we refer to this post on Legalmondo and to the replay of a recent webinar on mediation of international conflicts.

Dispute resolution clauses in international distribution agreements

The dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger led the parties to initiate two parallel lawsuits, one in the US (initiated by the distributor) and one in Japan (rooted by the manufacturer).

This was possible because the contract did not expressly foresee how any future disputes would be resolved, thus generating a very complicated situation, moreover on two judicial fronts in different countries.

The clauses that establish which law applies to a contract and how disputes are to be resolved are known as «midnight clauses«, because they are often the last clauses in the contract, negotiated late at night.

They are, in fact, very important clauses, which must be defined in a conscious way, to avoid solutions that are ineffective or counterproductive.

How we can help you

The construction of an international commercial distribution agreement is an important investment, because it sets the rules of the relationship between the parties for the future and provides them with the tools to manage all the situations that will be created in the future collaboration.

It is essential not only to negotiate and conclude a correct, complete and balanced agreement, but also to know how to manage it over the years, especially when situations of conflict arise.

Legalmondo offers the possibility to work with lawyers experienced in international commercial distribution in more than 60 countries: write us your needs.