-

France

France: Révision et renégociation des prix en cas de hausse des coûts

5 mai 2022

- Contrats

- Distribution

Résumé

Suivons l’histoire de Nike, tirée de la biographie de son fondateur Phil Knight, pour en tirer quelques leçons sur les contrats de distribution internationaux: comment négocier le contrat, établir la durée de l’accord, définir l’exclusivité et les objectifs commerciaux, et déterminer la manière adéquate de résoudre les litiges.

Ce dont je parle dans cet article

- Le conflit entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger et la naissance de Nike

- Comment négocier un accord de distribution international

- L’exclusivité contractuelle dans un accord de distribution commerciale

- Clauses de chiffre d’affaires minimum dans les contrats de distribution

- Durée du contrat et préavis de résiliation

- La propriété des marques dans les contrats de distribution commerciale

- L’importance de la médiation dans les contrats de distribution commerciale internationale

- Clauses de règlement des litiges dans les contrats internationaux

- Comment nous pouvons vous aider

Le différend entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger et la naissance de Nike

Pourquoi la marque de vêtements de sport la plus célèbre au monde est-elle Nike et non Onitsuka Tiger?

Shoe Dog est la biographie du créateur de Nike, Phil Knight: pour les amateurs du genre, mais pas seulement, le livre est vraiment très bon et je recommande sa lecture.

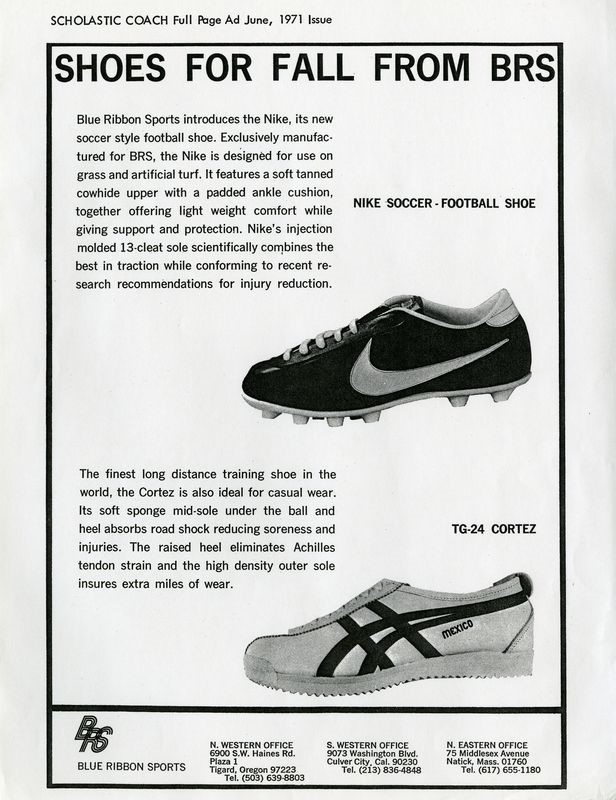

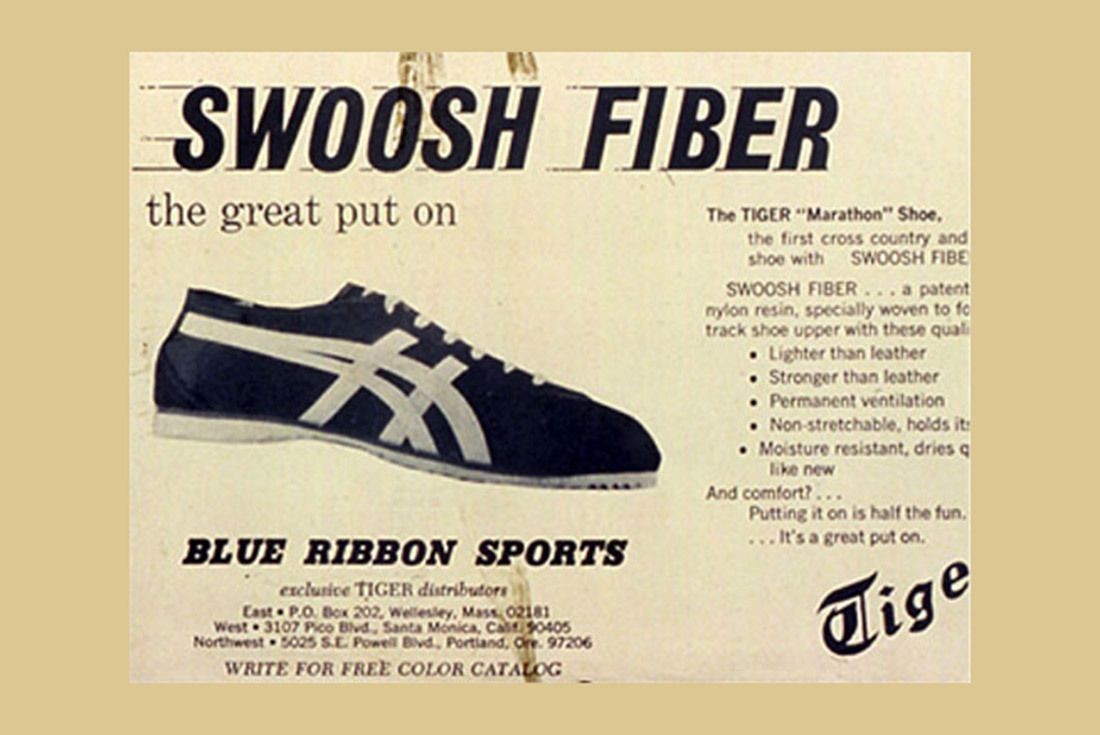

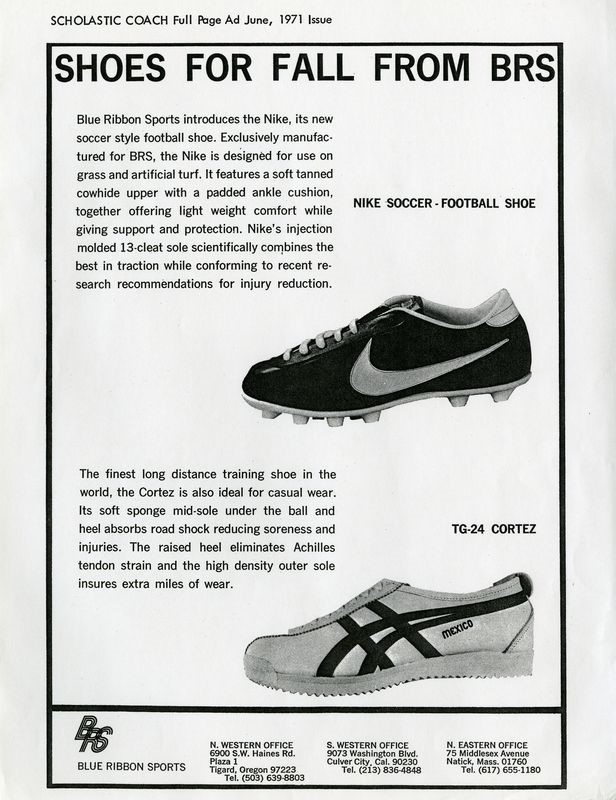

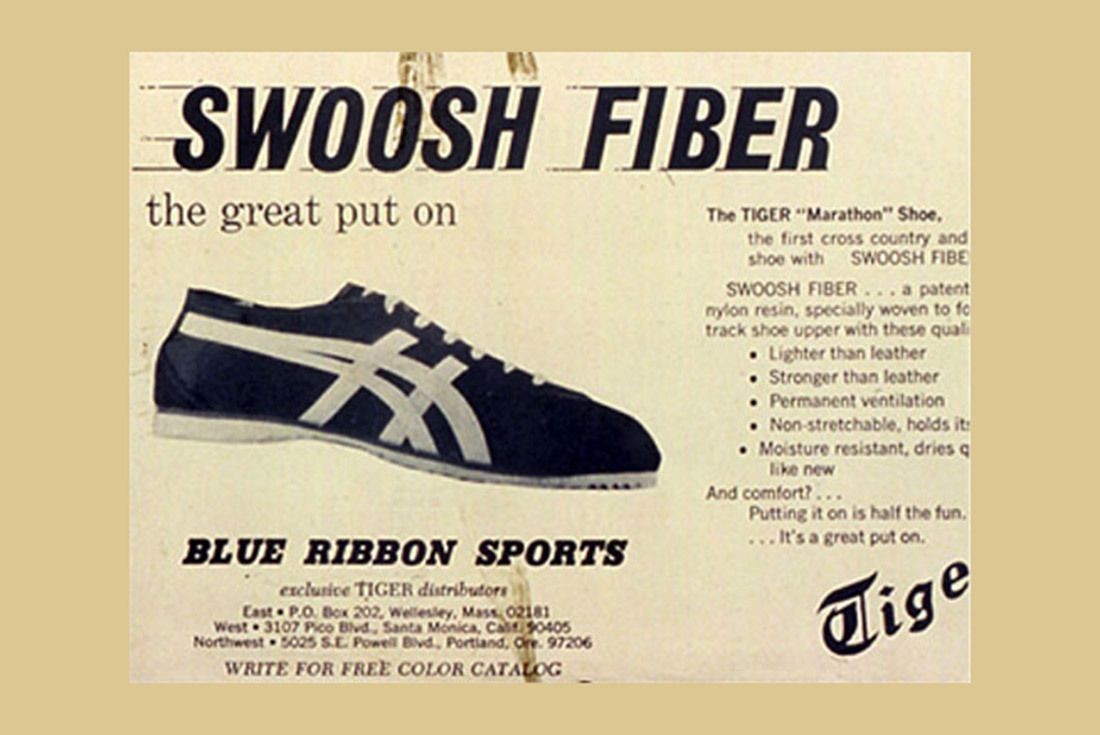

Mû par sa passion pour la course à pied et l’intuition qu’il y avait un espace dans le marché américain des chaussures de sport, à l’époque dominé par Adidas, Knight a été le premier, en 1964, à importer aux États-Unis une marque de chaussures de sport japonaise, Onitsuka Tiger, venant conquérir en 6 ans une part de marché de 70%.

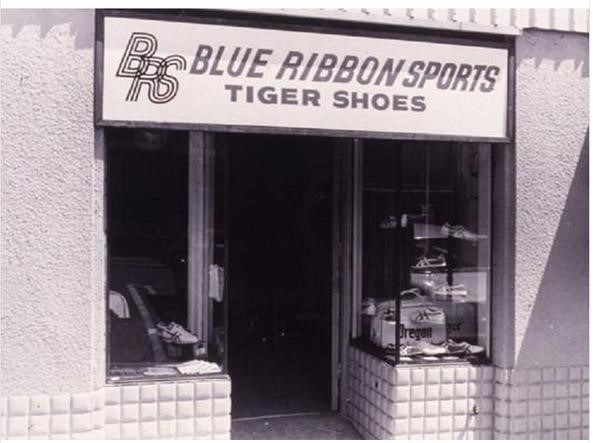

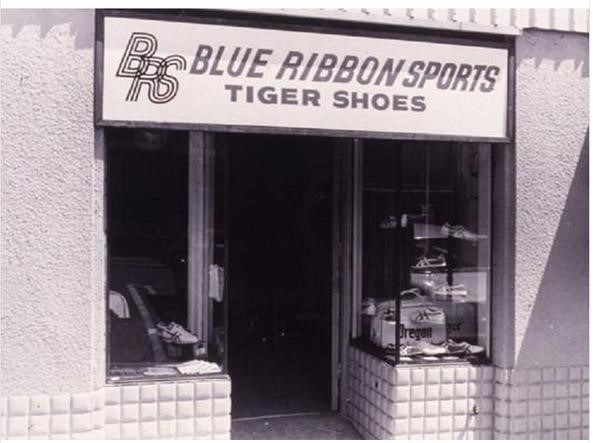

La société fondée par Knight et son ancien entraîneur d’athlétisme universitaire, Bill Bowerman, s’appelait Blue Ribbon Sports.

La relation d’affaires entre Blue Ribbon-Nike et le fabricant japonais Onitsuka Tiger a été, dès le début, très turbulente, malgré le fait que les ventes de chaussures aux États-Unis se déroulaient très bien et que les perspectives de croissance étaient positives.

Lorsque, peu après avoir renouvelé le contrat avec le fabricant japonais, Knight a appris qu’Onitsuka cherchait un autre distributeur aux États-Unis, craignant d’être coupé du marché, il a décidé de chercher un autre fournisseur au Japon et de créer sa propre marque, Nike.

En apprenant le projet Nike, le fabricant japonais a attaqué Blue Ribbon pour violation de l’accord de non-concurrence, qui interdisait au distributeur d’importer d’autres produits fabriqués au Japon, déclarant la résiliation immédiate de l’accord.

À son tour, Blue Ribbon a fait valoir que la violation serait celle d’Onitsuka Tiger, qui avait commencé à rencontrer d’autres distributeurs potentiels alors que le contrat était encore en vigueur et que les affaires étaient très positives.

Cela a donné lieu à deux procès, l’un au Japon et l’autre aux États-Unis, qui auraient pu mettre un terme prématuré à l’histoire de Nike.

Heureusement (pour Nike), le juge américain s’est prononcé en faveur du distributeur et le litige a été clos par un règlement: Nike a ainsi commencé le voyage qui l’amènera 15 ans plus tard à devenir la plus importante marque d’articles de sport au monde.

Comment négocier un accord de distribution commerciale internationale?

Voyons ce que l’histoire de Nike nous apprend et quelles sont les erreurs à éviter dans un contrat de distribution international.

Dans sa biographie, Knight écrit qu‘il a rapidement regretté d’avoir lié l’avenir de son entreprise à un accord commercial de quelques lignes rédigé à la hâte à la fin d’une réunion visant à négocier le renouvellement du contrat de distribution.

Que contenait cet accord?

L’accord prévoyait uniquement le renouvellement du droit de Blue Ribbon de distribuer les produits exclusivement aux Etats-Unis pour trois années supplémentaires.

Il arrive souvent que les contrats de distribution internationale soient confiés à des accords verbaux ou à des contrats très simples et de courte durée: l’explication qui est généralement donnée est qu’il est ainsi possible de tester la relation commerciale, sans trop engager la contrepartie.

Cette façon de faire est cependant erronée et dangereuse: le contrat ne doit pas être considéré comme une charge ou une contrainte, mais comme une garantie des droits des deux parties. Ne pas conclure de contrat écrit, ou le faire de manière très hâtive, signifie laisser sans accords clairs des éléments fondamentaux de la relation future, comme ceux qui ont conduit au litige entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger: objectifs commerciaux, investissements, propriété des marques.

Si le contrat est également international, la nécessité de rédiger un accord complet et équilibré est encore plus forte, étant donné qu’en l’absence d’accords entre les parties, ou en complément de ces accords, on applique une loi avec laquelle l’une des parties n’est pas familière, qui est généralement la loi du pays où le distributeur est basé.

Même si vous n’êtes pas dans la situation du Blue Ribbon, où il s’agissait d’un accord dont dépendait l’existence même de l’entreprise, les contrats internationaux doivent être discutés et négociés avec l’aide d’un avocat expert qui connaît la loi applicable à l’accord et peut aider l’entrepreneur à identifier et à négocier les clauses importantes du contrat.

Exclusivité territoriale, objectifs commerciaux et objectifs minimaux de chiffre d’affaires

La première raison du conflit entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger était l’évaluation de l’évolution des ventes sur le marché américain.

Onitsuka soutenait que le chiffre d’affaires était inférieur au potentiel du marché américain, alors que selon Blue Ribbon la tendance des ventes était très positive, puisque jusqu’à ce moment-là elle avait doublé chaque année le chiffre d’affaires, conquérant une part importante du secteur du marché.

Lorsque Blue Ribbon a appris qu’Onituska évaluait d’autres candidats pour la distribution de ses produits aux États-Unis et craignant d’être bientôt exclu du marché, Blue Ribbon a préparé la marque Nike comme plan B: lorsque cela a été découvert par le fabricant japonais, la situation s’est précipitée et a conduit à un différend juridique entre les parties.

Ce litige aurait peut-être pu être évité si les parties s’étaient mises d’accord sur des objectifs commerciaux et si le contrat avait inclus une clause assez classique dans les accords de distribution exclusive, à savoir un objectif de vente minimum de la part du distributeur.

Dans un accord de distribution exclusive, le fabricant accorde au distributeur une forte protection territoriale contre les investissements que le distributeur réalise pour développer le marché attribué.

Afin d’équilibrer la concession de l’exclusivité, il est normal que le producteur demande au distributeur ce que l’on appelle le chiffre d’affaires minimum garanti ou l’objectif minimum, qui doit être atteint par le distributeur chaque année afin de maintenir le statut privilégié qui lui est accordé.

Si l’objectif minimum n’est pas atteint, le contrat prévoit généralement que le fabricant a le droit de se retirer du contrat (dans le cas d’un accord à durée indéterminée) ou de ne pas le renouveler (si le contrat est à durée déterminée) ou de révoquer ou de restreindre l’exclusivité territoriale.

Dans le contrat entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger, l’accord ne prévoyait aucun objectif (et en fait, les parties n’étaient pas d’accord sur l’évaluation des résultats du distributeur) et venait d’être renouvelé pour trois ans: comment peut-on prévoir des objectifs de chiffre d’affaires minimum dans un contrat pluriannuel?

En l’absence de données fiables, les parties s’appuient souvent sur des mécanismes d’augmentation en pourcentage prédéterminés: +10% la deuxième année, +30% la troisième, +50% la quatrième, et ainsi de suite.

Le problème de cet automatisme est que les objectifs sont convenus sans disposer des données réelles sur l’évolution future des ventes du produit, des ventes des concurrents et du marché en général, et peuvent donc être très éloignés des possibilités actuelles de vente du distributeur.

Par exemple, contester le distributeur pour ne pas avoir atteint l’objectif de la deuxième ou troisième année dans une économie en récession serait certainement une décision discutable et une source probable de désaccord.

Il serait préférable de prévoir une clause de fixation consensuelle des objectifs d’une année sur l’autre, stipulant que les objectifs seront convenus entre les parties à la lumière des performances de vente des mois précédents, avec un certain préavis avant la fin de l’année en cours.

En cas d’absence d’accord sur le nouvel objectif, le contrat peut prévoir l’application de l’objectif de l’année précédente ou le droit pour les parties de se retirer, moyennant un certain délai de préavis.

D’autre part, il ne faut pas oublier que l’objectif peut également être utilisé comme une incitation pour le distributeur: il peut être prévu, par exemple, que si un certain chiffre d’affaires est atteint, cela permettra de renouveler l’accord, de prolonger l’exclusivité territoriale ou d’obtenir certaines compensations commerciales pour l’année suivante.

Une dernière recommandation est de gérer correctement la clause d’objectif minimum, si elle est présente dans le contrat: il arrive souvent que le fabricant conteste la non-atteinte de l’objectif pour une certaine année, après une longue période pendant laquelle les objectifs annuels n’avaient pas été atteints, ou n’avaient pas été actualisés, sans aucune conséquence.

Dans ce cas, il est possible que le distributeur invoque une renonciation implicite à cette protection contractuelle et donc que la rétractation ne soit pas valable: pour éviter les litiges à ce sujet, il est conseillé de prévoir expressément dans la clause Minimum Target que le fait de ne pas contester la non-atteinte de l’objectif pour une certaine période ne signifie pas que l’on renonce au droit d’activer la clause dans le futur.

Le délai de préavis pour la résiliation d’un contrat de distribution internationale

L’autre litige entre les parties concernait la violation d’un accord de non-concurrence: la vente de la marque Nike par Blue Ribbon, alors que le contrat interdisait la vente d’autres chaussures fabriquées au Japon.

Onitsuka Tiger a affirmé que Blue Ribbon avait violé l’accord de non-concurrence, tandis que le distributeur a estimé qu’il n’avait pas d’autre choix, étant donné la décision imminente du fabricant de résilier l’accord.

Ce type de litige peut être évité en fixant clairement une période de préavis pour la résiliation (ou le non-renouvellement): cette période a pour fonction fondamentale de permettre aux parties de se préparer à la fin de la relation et d’organiser leurs activités après la résiliation.

En particulier, afin d’éviter des malentendus tels que celui qui s’est produit entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger, on peut prévoir que, pendant cette période, les parties pourront prendre contact avec d’autres distributeurs et producteurs potentiels, et que cela ne viole pas les obligations d’exclusivité et de non-concurrence.

Dans le cas de Blue Ribbon, en effet, le distributeur avait fait un pas de plus que la simple recherche d’un autre fournisseur, puisqu’il avait commencé à vendre des produits Nike alors que le contrat avec Onitsuka était encore valide: ce comportement représente une grave violation d’un accord d’exclusivité.

Un aspect particulier à prendre en considération concernant le délai de préavis est sa durée: quelle doit être la durée du préavis pour être considéré comme équitable ? Dans le cas de relations commerciales de longue date, il est important de donner à l’autre partie suffisamment de temps pour se repositionner sur le marché, en cherchant d’autres distributeurs ou fournisseurs, ou (comme dans le cas de Blue Ribbon/Nike) pour créer et lancer sa propre marque.

L’autre élément à prendre en compte, lors de la communication de la résiliation, est que le préavis doit être tel qu’il permette au distributeur d’amortir les investissements réalisés pour remplir ses obligations pendant le contrat; dans le cas de Blue Ribbon, le distributeur, à la demande expresse du fabricant, avait ouvert une série de magasins monomarques tant sur la côte ouest que sur la côte est des États-Unis.

Une clôture du contrat peu après son renouvellement et avec un préavis trop court n’aurait pas permis au distributeur de réorganiser le réseau de vente avec un produit de remplacement, obligeant la fermeture des magasins qui avaient vendu les chaussures japonaises jusqu’à ce moment.

En général, il est conseillé de prévoir un délai de préavis pour la résiliation d’au moins 6 mois, mais dans les contrats de distribution internationale, il faut prêter attention, en plus des investissements réalisés par les parties, aux éventuelles dispositions spécifiques de la loi applicable au contrat (ici, par exemple, une analyse approfondie pour la résiliation brutale des contrats en France) ou à la jurisprudence en matière de rupture des relations commerciales (dans certains cas, le délai considéré comme approprié pour un contrat de concession de vente à long terme peut atteindre 24 mois).

Enfin, il est normal qu’au moment de la clôture du contrat, le distributeur soit encore en possession de stocks de produits: cela peut être problématique, par exemple parce que le distributeur souhaite généralement liquider le stock (ventes flash ou ventes via des canaux web avec de fortes remises) et cela peut aller à l’encontre des politiques commerciales du fabricant et des nouveaux distributeurs.

Afin d’éviter ce type de situation, une clause qui peut être incluse dans le contrat de distribution est celle relative au droit du producteur de racheter le stock existant à la fin du contrat, en fixant déjà le prix de rachat (par exemple, égal au prix de vente au distributeur pour les produits de la saison en cours, avec une remise de 30% pour les produits de la saison précédente et avec une remise plus importante pour les produits vendus plus de 24 mois auparavant).

Propriété de la marque dans un accord de distribution international

Au cours de la relation de distribution, Blue Ribbon avait créé un nouveau type de semelle pour les chaussures de course et avait inventé les marques Cortez et Boston pour les modèles haut de gamme de la collection, qui avaient connu un grand succès auprès du public, gagnant une grande popularité: à la fin du contrat, les deux parties ont revendiqué la propriété des marques.

Des situations de ce type se produisent fréquemment dans les relations de distribution internationale: le distributeur enregistre la marque du fabricant dans le pays où il opère, afin d’empêcher les concurrents de le faire et de pouvoir protéger la marque en cas de vente de produits contrefaits ; ou bien il arrive que le distributeur, comme dans le litige dont nous parlons, collabore à la création de nouvelles marques destinées à son marché.

À la fin de la relation, en l’absence d’un accord clair entre les parties, un litige peut survenir comme celui de l’affaire Nike: qui est le propriétaire, le producteur ou le distributeur?

Afin d’éviter tout malentendu, le premier conseil est d’enregistrer la marque dans tous les pays où les produits sont distribués, et pas seulement: dans le cas de la Chine, par exemple, il est conseillé de l’enregistrer quand même, afin d’éviter que des tiers de mauvaise foi ne s’approprient la marque (pour plus d’informations, voir ce billet sur Legalmondo).

Il est également conseillé d’inclure dans le contrat de distribution une clause interdisant au distributeur de déposer la marque (ou des marques similaires) dans le pays où il opère, en prévoyant expressément le droit pour le fabricant de demander son transfert si tel était le cas.

Une telle clause aurait empêché la naissance du litige entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger.

Les faits que nous relatons datent de 1976: aujourd’hui, en plus de clarifier la propriété de la marque et les modalités d’utilisation par le distributeur et son réseau de vente, il est conseillé que le contrat réglemente également l’utilisation de la marque et des signes distinctifs du fabricant sur les canaux de communication, notamment les médias sociaux.

Il est conseillé de stipuler clairement que le fabricant est le propriétaire des profils de médias sociaux, des contenus créés et des données générées par l’activité de vente, de marketing et de communication dans le pays où opère le distributeur, qui ne dispose que de la licence pour les utiliser, conformément aux instructions du propriétaire.

En outre, il est bon que l’accord établisse la manière dont la marque sera utilisée et les politiques de communication et de promotion des ventes sur le marché, afin d’éviter des initiatives qui pourraient avoir des effets négatifs ou contre-productifs.

La clause peut également être renforcée en prévoyant des pénalités contractuelles dans le cas où, à la fin du contrat, le distributeur refuserait de transférer le contrôle des canaux numériques et des données générées dans le cadre de l’activité commerciale.

La médiation dans les contrats de distribution commerciale internationale

Un autre point intéressant offert par l’affaire Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger est lié à la gestion des conflits dans les relations de distribution internationale: des situations telles que celle que nous avons vue peuvent être résolues efficacement par le recours à la médiation.

C’est une tentative de conciliation du litige, confiée à un organisme spécialisé ou à un médiateur, dans le but de trouver un accord amiable qui évite une action judiciaire.

La médiation peut être prévue dans le contrat comme une première étape, avant l’éventuel procès ou arbitrage, ou bien elle peut être initiée volontairement dans le cadre d’une procédure judiciaire ou arbitrale déjà en cours.

Les avantages sont nombreux: le principal est la possibilité de trouver une solution commerciale qui permette la poursuite de la relation, au lieu de chercher uniquement des moyens de mettre fin à la relation commerciale entre les parties.

Un autre aspect intéressant de la médiation est celui de surmonter les conflits personnels: dans le cas de Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka, par exemple, un élément décisif dans l’escalade des problèmes entre les parties était la relation personnelle difficile entre le PDG de Blue Ribbon et le directeur des exportations du fabricant japonais, aggravée par de fortes différences culturelles.

Le processus de médiation introduit une troisième figure, capable de dialoguer avec les parties et de les guider dans la recherche de solutions d’intérêt mutuel, qui peut être décisive pour surmonter les problèmes de communication ou les hostilités personnelles.

Pour ceux qui sont intéressés par le sujet, nous vous renvoyons à ce post sur Legalmondo et à la rediffusion d’un récent webinaire sur la médiation des conflits internationaux.

Clauses de règlement des différends dans les accords de distribution internationaux

Le litige entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger a conduit les parties à engager deux procès parallèles, l’un aux États-Unis (initié par le distributeur) et l’autre au Japon (enraciné par le fabricant).

Cela a été possible parce que le contrat ne prévoyait pas expressément la manière dont les litiges futurs seraient résolus, générant ainsi une situation très compliquée, de plus sur deux fronts judiciaires dans des pays différents.

Les clauses qui établissent la loi applicable à un contrat et la manière dont les litiges doivent être résolus sont connues sous le nom de « clauses de minuit », car elles sont souvent les dernières clauses du contrat, négociées tard dans la nuit.

Ce sont, en fait, des clauses très importantes, qui doivent être définies de manière consciente, afin d’éviter des solutions inefficaces ou contre-productives.

Comment nous pouvons vous aider

La construction d’un accord de distribution commerciale internationale est un investissement important, car il fixe les règles de la relation entre les parties pour l’avenir et leur fournit les outils pour gérer toutes les situations qui seront créées dans la future collaboration.

Il est essentiel non seulement de négocier et de conclure un accord correct, complet et équilibré, mais aussi de savoir le gérer au fil des années, surtout lorsque des situations de conflit se présentent.

Legalmondo offre la possibilité de travailler avec des avocats expérimentés dans la distribution commerciale internationale dans plus de 60 pays: écrivez-nous vos besoins.

Résumé

Les crises politiques, environnementales et sanitaires (telles que la crise sanitaire du Covid-19 et l’agression de l’Ukraine par l’armée russe) peuvent provoquer l’augmentation du prix des matières premières et composants et une inflation généralisée. Aussi bien les fournisseurs que les distributeurs se retrouvent confrontés à des problèmes liés à la hausse, souvent soudaine, et très substantielle, des prix de leurs approvisionnements. Le droit français pose à ce égard un certain nombre de règles spéciales constituant autant d’opportunités que de contraintes selon les intérêts en présence.

Deux situations principales peuvent être distinguées (outre de nombreux accords ou situations particuliers): celle dans laquelle les parties n’ont pas figé les conditions tarifaires (le plus souvent en instaurant un simple flux courant de commandes ou en concluant un contrat cadre sans engagement de prix ferme sur une durée déterminée) et celle dans laquelle les parties ont conclu un accord cadre figeant les prix pendant une durée déterminée.

La révision des prix dans une relation d’affaires

La situation est la suivante : les parties n’ont pas conclu d’accord cadre, chaque contrat de vente conclu (chaque commande) est régi par les CGV du fournisseur ; ce dernier ne s’est pas engagé à maintenir les prix pendant une durée minimum et applique les prix du tarif en cours.

En principe, le fournisseur peut modifier ses prix à tout moment en adressant un nouveau tarif. Il devra cependant accorder par écrit un préavis raisonnable conforme aux dispositions de l’article L. 442-1.II du code de commerce, avant que son augmentation de prix n’entre en vigueur. Faute de respecter un préavis suffisant, il pourrait se voir reprocher une rupture brutale « partielle » des relations commerciales (et s’exposer à des dommages-intérêts).

Une rupture brutale consécutive à une augmentation de prix est caractérisée quand les conditions suivantes sont réunies :

- la relation commerciale doit être établie : notion plus large que le simple contrat, en tenant compte de la durée mais aussi de l’importance et de la régularité des échanges entre les parties ;

- l’augmentation de prix doit être assimilée à une rupture : c’est principalement l’importance de l’augmentation des prix (+1%, 10% ou 25% ?) qui conduira un juge à déterminer si l’augmentation constitue une rupture « partielle » (en cas de modification substantielle de la relation qui est néanmoins maintenue) ou une rupture totale (si l’augmentation est telle qu’elle implique un arrêt de la relation) ou si elle ne constitue pas une rupture (si la hausse est minime) ;

- le préavis accordé est insuffisant en comparant la durée du préavis effectivement accordé à celle du préavis conforme à l’article L. 442-1.II, tenant compte, notamment, de la durée de la relation commerciale et de l’éventuelle dépendance de la victime de la rupture à l’égard de l’autre partie.

L’article L. 442-1.II est d’ordre public dans les relations internes françaises. Dans les relations commerciales internationales, pour savoir comment traiter l’article L.442-1.II et les règles de conflits de lois ainsi que les règles de compétence juridictionnelle, veuillez consulter notre précédent article publié sur le blog Legalmondo.

La révision des prix dans un contrat-cadre

Si les parties ont conclu un contrat-cadre (tels que approvisionnement, fabrication, …) de plusieurs années et que le fournisseur s’est engagé sur un tarif ferme, comment, dans ce cas, peut-il augmenter ses prix ? Indépendamment d’une clause d’indexation ou d’une clause de renégociation qui serait stipulée au contrat (outre les dispositions légales spécifiques applicables aux conventions particulières quant à leur nature ou à leur secteur économique), le fournisseur peut chercher à se prévaloir du mécanisme légal de « l’imprévision » prévu par l’article 1195 du code civil,

Ce mécanisme ne permet pas au fournisseur de modifier unilatéralement ses prix mais lui permet de négocier leur adaptation avec son client.

Trois conditions préalables doivent être cumulativement réunies:

- un changement de circonstances imprévisible lors de la conclusion du contrat (i.e. : les parties ne pouvaient pas raisonnablement anticiper ce bouleversement);

- une exécution du contrat devenue excessivement onéreuse (i.e. : au-delà de la simple difficulté, le bouleversement doit causer un déséquilibre de l’ordre de la disproportion);

- l’absence d’acceptation de ces risques par le débiteur de l’obligation lors de la conclusion du contrat.

La mise en œuvre de ce mécanisme doit suivre les étapes suivantes:

- d’abord, la partie en difficulté doit demander la renégociation du contrat à son cocontractant;

- ensuite, en cas d’échec de la négociation ou de refus de négocier de l’autre partie, les parties peuvent convenir ensemble (i) de la résolution du contrat, à la date et aux conditions qu’elles déterminent, ou (ii) de demander au juge compétent de procéder à son adaptation;

- enfin, à défaut d’accord des parties sur l’une des deux options précitées, dans un délai raisonnable, le juge, saisi par l’une des parties, peut réviser le contrat ou y mettre fin, à la date et aux conditions qu’il fixe.

La partie voulant mettre en œuvre ce mécanisme légal doit aussi anticiper les points suivants:

- l’article 1195 du code civil ne s’applique qu’aux contrats conclus à compter du 1er octobre 2016 (ou renouvelés après cette date). Les juges n’ont pas le pouvoir d’adapter ou rééquilibrer les contrats conclus avant cette date;

- cette disposition n’est pas d’ordre public dans les relations internes (ni une loi de police au en matière internationale). Dès lors, les parties peuvent l’exclure ou modifier ses conditions d’application et/ou de mise en œuvre (le plus courant étant l’encadrement des pouvoirs du juge);

- durant la renégociation le fournisseur devra continuer à vendre au prix initial car, contrairement à la force majeure, l’imprévision n’entraîne pas la suspension du respect des obligations.

Points clefs à retenir:

- analyser avec attention le cadre de la relation commerciale avant de décider de notifier une augmentation des prix, afin d’identifier si les prix sont fermes sur une durée minimum et les leviers contractuels de renégociation;

- identifier correctement la durée du préavis devant être accordé au partenaire avant l’entrée en vigueur des nouvelles conditions tarifaires, selon l’ancienneté de la relation et le degré de dépendance;

- documenter la hausse de prix;

- vérifier si et comment le mécanisme légal de l’imprévision a été amendé ou exclu par le contrat-cadre ou les CGV ou les CPV;

- envisager des alternatives fondées éventuellement sur l’arrêt des productions/ livraisons en se retranchant, si cela est possible, derrière un cas de force majeure ou sur le déséquilibre significatif des dispositions contractuelles.

Résumé

A la fin des contrats d’agence et de distribution, la principale source de conflit est l’indemnité de clientèle. La loi espagnole sur le contrat d’agence -comme la directive sur les agents commerciaux- prévoit que lorsque le contrat prend fin, l’agent aura droit, si certaines conditions sont remplies, à une indemnité. En Espagne, par analogie (mais avec des qualifications et des nuances), cette indemnité peut également être réclamée dans les contrats de distribution.

Pour que l’indemnité de clientèle soit reconnue, il est nécessaire que l’agent (ou le distributeur : voir ce post pour en savoir plus) ait apporté de nouveaux clients ou augmenté de manière significative les opérations avec les clients préexistants, que son activité puisse continuer à produire des bénéfices substantiels pour le commettant et qu’elle soit équitable. Tout cela conditionnera la reconnaissance du droit à l’indemnisation et son montant.

Ces expressions (nouveaux clients, augmentation significative, peut produire, avantages substantiels, équitable) sont difficiles à définir au préalable, c’est pourquoi, pour avoir du succès, il est recommandé que les demandes devant les tribunaux soient appuyées, au cas par cas, sur des rapports d’experts, supervisés par un avocat.

Il existe, du moins en Espagne, une tendance à réclamer directement le maximum prévu par la norme (une année de rémunération calculée comme la moyenne des cinq années précédentes) sans procéder à une analyse plus approfondie. Mais si cela est fait, il y a un risque que le juge rejette la requête comme non fondée.

Par conséquent, et sur la base de notre expérience, je trouve opportun de fournir des conseils sur la manière de mieux étayer la demande de cette indemnité et son montant.

L’agent/distributeur, l’expert et l’avocat devraient considérer les points suivants:

Vérifier quelle a été la contribution de l’agent

S’il y avait des clients avant le début du contrat et quel volume de ventes a été réalisé avec eux. Pour reconnaître cette compensation, il est nécessaire que l’agent ait augmenté le nombre de clients ou d’opérations avec des clients préexistants.

Analysez l’importance de ces clients lorsqu’il s’agit de continuer à fournir des prestations au mandant

Leur récurrence, leur fidélité (au mandant et non à l’agent), le taux de migration (combien d’entre eux resteront avec le mandant à la fin du contrat, ou avec l’agent). En effet, il sera difficile de parler de « clientèle » s’il n’y a eu que des clients sporadiques, occasionnels, non récurrents (ou peu) ou qui resteront fidèles à l’agent et non au mandant.

Comment l’agent opère-t-il à la fin du contrat?

Peut-il faire concurrence au commettant ou y a-t-il des restrictions dans le contrat ? Si l’agent peut continuer à servir les mêmes clients, mais pour un autre mandant, la rémunération pourrait être très discutée.

La rémunération est-elle équitable?

Examinez comment l’agent a agi dans le passé : s’il a rempli ses obligations, son travail lors de l’introduction des produits ou de l’ouverture du marché, l’évolution possible de ces produits ou services à l’avenir, etc.

L’agent perdra-t-il des commissions?

Ici, nous devons examiner s’il avait l’exclusivité ; sa plus ou moins grande facilité à obtenir un nouveau contrat (par exemple, en raison de son âge, de la crise économique, du type de produits, etc.) ou avec une nouvelle source de revenus, l’évolution des ventes au cours des dernières années (celles considérées pour la compensation), etc.

Quel est le maximum légal qui ne peut être dépassé?

La moyenne annuelle du montant perçu pendant la durée du contrat (ou 5 ans s’il a duré plus longtemps). Cela comprendra non seulement les commissions, mais aussi les montants fixes, les primes, les prix, etc. ou les marges dans le cas des distributeurs.

Enfin, il convient d’inclure tous les documents analysés dans le rapport d’expertise

Si cela n’est pas fait et qu’ils ne sont que mentionnés, cela pourrait avoir pour conséquence qu’ils ne soient pas pris en compte par un juge.

Consultez le guide pratique sur les agents de l’agence internationale

Pour en savoir plus sur les principales caractéristiques d’un contrat d’agence en Espagne, consultez notre Guide.

Summary

By means of Legislative Decree No. 198 of November 8th, 2021, Italy implemented Directive (EU) 2019/633 on unfair trading practices in business-to-business relationships in the agricultural and food supply chain. The Italian legislator introduced stricter rules than those provided for in the directive. Moreover, it has provided for some mandatory contractual requirements, within the framework of Article 168 of Regulation (EC) 1308/2013, but more restrictive than those of the Regulation. The new provisions shall apply irrespective of the law applicable to the contract and the country of the buyer, hence they concern cross-border relationships as well. They significantly impact contractual relationships related to the chain of fresh and processed food products, including wine, and certain non-food agricultural products, and require companies in the concerned sectors to review their contracts and business practices with respect to their relationships with customers and suppliers.

The provisions introduced by the decree also apply to existing contracts, which shall be made compliant by 15 June 2022.

Introduction

With Directive (EU) 2019/633, the EU legislator introduced a detailed set of unfair trading practices in business-to-business relationships in the agricultural and food supply chain, in order to tackle unbalanced trading practices imposed by strong contractual parties. The directive has been transposed in Italy by Legislative Decree No. 198 of November 8th, 2021 (it came into force on December 15th, 2021), which introduced a long list of provisions qualified as unfair trading practices in the context of business-to-business relationships in the agricultural and food supply chain. The list of unfair practices is broader than the one provided for in the EU directive.

The transposition of the directive was also the opportunity to introduce some mandatory requirements to contracts for the supply of goods falling within the scope of the decree. These requirements, adopted in the framework of Article 168 of Regulation (EC) 1308/2013, replaced and extended those provided for in Article 62 of Decree-Law 1/2012 and Article 10-quater of Decree-Law 27/2019.

Scope of application

The legislation applies to commercial relationships between buyers (including the public administration) and suppliers of agricultural and food products and in particular to B2B contracts having as object the transfer of such products.

It does not apply to agreements in which a consumer is party, to transfers with simultaneous payment and delivery of the goods and transfers of products to cooperatives or producer organisations within the meaning of Legislative Decree 102/2005.

It applies, inter alia, to sale, supply and distribution agreements.

Agricultural and food products means the goods listed in Annex I of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, as well as those not listed in that Annex but processed for use as food using listed products. This includes all products of the agri-food chain, fresh and processed, including wine, as well as certain agricultural products outside the food chain, including animal feed not intended for human consumption and floricultural products.

The rules apply to sales made by suppliers based in Italy, whilst the country where the buyer is based is not relevant. It applies irrespective of the law applicable to the relationship between the parties. Therefore, the new rules also apply in case of international contractual relationships subject to the law of another country.

In transposing the directive, the Italian legislator decided not to take into consideration the « size of the parties »: while the directive provides for turnover thresholds and applies to contractual relations in which the buyer has a turnover equal to or greater than the supplier, the Italian rules apply irrespective of the turnover of the parties.

Contractual requirements

Article 3 of the decree introduced some mandatory requirements for contracts for the supply or transfer of agricultural and food products. These requirements, adopted in the framework of Article 168 of Regulation (EC) 1308/2013, replaced and extended those established by Article 62 of Decree-Law 1/2012 and Article 10-quater of Decree-Law 27/2019 (which had been repealed).

Contracts must comply with the principles of transparency, fairness, proportionality and mutual consideration of performance.

Contracts must be in writing. Equivalent forms (transport documents, invoices and purchase orders) are only allowed if a framework agreement containing the essential terms of future supply agreements has been entered into between supplier and buyer.

Of great impact is the requirement for contracts to have a duration of at least 12 months (contracts with a shorter duration are automatically extended to the minimum duration). The legislator requires companies in the supply chain (with some exceptions) to operate not with individual purchases but with continuous supply agreements, which shall indicate the quantity and characteristics of the products, the price, the delivery and payment method.

A considerable operational change is required due to the need to plan and contract quantities and prices of supplies. As far as the price is concerned, it no longer seems possible to agree on it from time to time during the relationship on the basis of orders or new price lists from the supplier. The price may be fixed or determinable according to the criteria laid down in the contract. Therefore, companies not intending to operate at a fixed price will have to draft contractual clauses containing the criteria for determining the price (e.g. linking it to stock exchange quotations, fluctuations in raw material or energy prices).

The minimum duration of at least 12 months may be waived. However, the derogation shall be justified, either by the seasonality of the products or other reasons (that are not specified in the decree). Other reasons could include the need for the buyer to meet an unforeseen increase in demand, or the need to replace a lost supply.

The provisions described above may also be derogated from by framework agreements concluded by the most representative business organisations.

Prohibited unfair trading practices and specific derogations

The decree provides for several cases qualified as unfair trading practices, some of which are additional to those provided for in the directive.

Article 4 contains two categories of prohibited practices, which transpose those of the directive.

The first concerns practices which are always prohibited, including, first of all, payment of the price after 30 days for perishable products and after 60 days for non-perishable products. This category also includes the cancellation of orders for perishable goods at short notice; unilateral amendments to certain contractual terms; requests for payments not related to the sale; contractual clauses obliging the supplier to bear the cost of deterioration or loss of the goods after delivery; refusal by the buyer to confirm the contractual terms in writing; the acquisition, use and disclosure of the supplier’s trade secrets; the threat of commercial retaliation by the buyer against the supplier who intends to exercise contractual rights; and the claim by the buyer for the costs incurred in examining customer complaints relating to the sale of the supplier’s products.

The second category relates to practices which are prohibited unless provided for in a written agreement between the parties: these include the return of unsold products without payment for them or for their disposal; requests to the supplier for payments for stoking, displaying or listing the products or making them available on the market; requests to the supplier to bear the costs of discounts, advertising, marketing and personnel of the buyer to fitting-out premises used for the sale of the products.

Article 5 provides for further practices always prohibited, in addition to those of the directive, such as the use of double-drop tenders and auctions (“gare ed aste a doppio ribasso”); the imposition of contractual conditions that are excessively burdensome for the supplier; the omission from the contract of the terms and conditions set out in Article 168(4) of Regulation (EU) 1308/2013 (among which price, quantity, quality, duration of the agreement); the direct or indirect imposition of contractual conditions that are unjustifiably burdensome for one of the parties; the application of different conditions for equivalent services; the imposition of ancillary services or services not related to the sale of the products; the exclusion of default interest to the detriment of the creditor or of the costs of debt collection; clauses imposing on the supplier a minimum time limit after delivery in order to be able to issue the invoice; the imposition of the unjustified transfer of economic risk on one of the parties; the imposition of an excessively short expiry date by the supplier of products, the maintenance of a certain assortment of products, the inclusion of new products in the assortment and privileged positions of certain products on the buyer’s premises.

A specific discipline is provided for sales below cost: Article 7 establishes that, as regards fresh and perishable products, this practice is allowed only in case of unsold products at risk of perishing or in case of commercial operations planned and agreed with the supplier in writing, while in the event of violation of this provision the price established by the parties is replaced by law.

Sanctioning system and supervisory authorities

The provisions introduced by the decree, as regards both contractual requirements and unfair trading practices, are backed up by a comprehensive system of sanctions.

Contractual clauses or agreements contrary to mandatory contractual requirements, those that constitute unfair trading practices and those contrary to the regulation of sales below cost are null and void.

The decree provides for specific financial penalties (one for each case) calculated between a fixed minimum (which, depending on the case, may be from 1,000 to 30,000 euros) and a variable maximum (between 3 and 5%) linked to the turnover of the offender; there are also certain cases in which the penalty is further increased.

In any event, without prejudice to claims for damages.

Supervision of compliance with the provisions of the decree is entrusted to the Central Inspectorate for the Protection of Quality and Fraud Repression of Agri-Food Products (ICQRF), which may conduct investigations, carry out unannounced on-site inspections, ascertain violations, require the offender to put an end to the prohibited practices and initiate proceedings for the imposition of administrative fines, without prejudice to the powers of the Competition and Market Authority (AGCM).

Recommended activities

The provisions introduced by the decree also apply to existing contracts, which shall be made compliant by 15 June 2022. Therefore:

- the companies involved, both Italian and foreign, should carry out a review of their business practices, current contracts and general terms and conditions of supply and purchase, and then identify any gaps with respect to the new provisions and adopt the relevant corrective measures.

- As the new legislation applies irrespective of the applicable law and is EU-derived, it will be important for companies doing business abroad to understand how the EU directive has been implemented in the countries where they operate and verify the compliance of contracts with these rules as well.

In an important and very reasoned judgment delivered by the Court of Cassation of France on September 30, 2020, relating to the enforceability of arbitration clauses in international consumer contracts, the Supreme Court judged that these clauses must be considered unfair and cannot be opposed to consumers.

The Supreme Court traditionally insisted on the priority given to the arbitrator to decide on his own jurisdiction, laid down in Article 1448 of the Code of Civil Procedure (principle known as « competence-competence », Jaguar, Civ. 1re, May 21, 1997, nos. 95-11.429 and 95-11.427).

The ECJ expressed its hostility towards such clauses when they are opposed to consumers. In Mostaza Claro (C-168/05), it referred to the internal laws of member states, while considering that the procedural modalities offered by states should not “make it impossible in practice or excessively difficult to exercise the rights conferred by public order to consumers (“Directive 93/13, concerning unfair terms in consumer contracts, must be interpreted as meaning that a national court seized of an action for annulment of an arbitration award must determine whether the arbitration agreement is void and annul that award where that agreement contains an unfair term, even though the consumer has not pleaded that invalidity in the course of the arbitration proceedings, but only in that of the action for annulment”).

It therefore referred to the national judge the right to implement its legislation on unfair terms, and therefore to decide, on a case-by-case basis, whether the arbitration clause should be considered unfair. This is what the Court of Cassation decided, ruling out the case-by-case method, and considering that in any event such a clause must be excluded in relations with consumers.

The Court of Cassation adopted the same solution in international employment contracts, where it traditionally considers that arbitration clauses contained in international employment contracts are enforceable against employee (Soc. 16 Feb. 1999, n ° 96-40.643).

The Supreme Court, although traditionally very favourable to arbitration, gradually builds up a set of specific exceptions to ensure the protection of the « weak » party.

Summary

The recent post-Brexit trade deal makes no provision for jurisdiction or the enforcement of judgments.

Therefore, the UK dropped out of the jurisdiction of the Brussels (Recast) Regulation (No. 1215/2012) on 31 December 2020.

The EU has not yet approved the UK’s accession to the Lugano Convention, but may do in the future.

Unless the transitional provisions from the Withdrawal Agreement apply, jurisdiction and enforcement of judgments will be governed by the Hague Convention 2005 if there is an applicable exclusive jurisdiction clause

If the Hague Convention of 2005 does not apply, then the UK and EU courts will apply their own national rules.

Judgments will continue to be reciprocally enforceable between the UK and Norway from 1 January 2021.

On the first day of 2021 the UK left the EU regimes with which European lawyers are familiar. We appeared to enter “uncharted territory”. Not so. In fact, there are charts for this territory – or maps, to use a more modern word. You just need to know which maps.

Whether you are a lawyer or a businessperson, in whatever country, you need answers to two questions. Which laws govern jurisdiction and enforcement of judgments between EU member states and the UK; and how should businesses act as a result?

What happened?

The EU and UK reached a post-Brexit trade deal, the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (“TCA”), on Christmas Eve 2020. The provisions of the TCA became UK law as the European Union (Future Relationship) Act on 31 December 2020. The TCA made provision for judicial cooperation in criminal matters, but did not mention judicial cooperation in civil matters, or jurisdiction and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial proceedings.

So where do we look for law on those matters?

We look at the position immediately before Brexit. As every lawyer should know the Brussels (Recast) Regulation (No. 1215/2012) governed the enforcement and recognition of judgments between EU member states.

Also, the Lugano Convention 2007 governs jurisdiction and enforcement of judgments in commercial and civil matters between EU member states and Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. It operates in substantially the same way as Brussels (Recast) does between EU member states.

The UK was party to the Convention by virtue of its EU membership. Now that the UK is not a member of the EU, the contracting parties could agree that the UK could join the Lugano Convention as an independent contracting party, and there would be little change to the position on jurisdiction and enforcement. English jurisdiction clauses would continue to be respected and English court judgments would continue to be readily enforceable throughout EU member states and EFTA countries, and vice versa.

The problem is that the EU has not agreed to the UK joining the Lugano Convention

The UK submitted its application to accede to the Lugano Convention in its own right on 8 April 2020. But accession requires the consent of all contracting parties including the EU. Iceland, Norway and Switzerland have indicated their support for the UK’s accession, but the EU’s position is still not yet clear and the TCA is silent on this matter.

While the EU still may belatedly support the UK’s accession to Lugano, it does not currently apply. In any case, a three-month time-lag applies between agreement and entry into force, unless all the contracting parties agree to waive it.

Where are we now?

If the transitional provisions provided for by the Withdrawal Agreement as explained in my previous post do not apply, the Brussels (Recast) Regulation will not apply to jurisdiction and enforcement between the EU and UK.

If they do not, then you first need to decide whether the Hague Convention on Choice of Court Agreements 2005 is applicable. The Hague Convention 2005 applies between EU Member States, Mexico, Singapore and Montenegro. The Hague Convention first came into force for the UK when the EU acceded on 1 October 2015 and the UK re-acceded after Brexit in its own right with effect from 1 January 2021.

The Hague Convention 2005 applies if:

- The dispute falls within the scope of the Convention as provided for by Article 2 – e.g. the Convention does not apply to employment and consumer contracts or claims for personal injury;

- There is an exclusive jurisdiction clause within the meaning of Article 3; and

- The exclusive jurisdiction clause is entered into after the Convention came into force for the country whose courts are seized, and proceedings are commenced after the Convention came into force for the country whose courts are seized within the meaning of Article 16.

There is some uncertainty as to whether EU member states will treat the Hague Convention as having been in force from 1 October 2015, or only from when the UK re-accedes on 1 January 2021. The UK’s view is that the Convention will apply to the UK from 1 October 2015; the EU’s view is that it will apply to the UK from 1 January 2021. What is not in dispute is that for exclusive English jurisdiction clauses agreed on or after 1 January 2021, the contracting states will respect exclusive English jurisdiction clauses and enforce the resulting judgments.

If the 2005 Hague Convention does not apply, then the UK and EU courts will apply their own national rules to questions of jurisdiction and enforcement. In the UK, the rules will essentially be the same as the ‘common-law’ rules currently on enforcement applied to non-EU parties, for example the United States.

The Norwegian exception

The UK and Norway have reached an agreement which extends and updates an old mutual enforcement treaty, the 1961 Convention for the Reciprocal Recognition and Enforcement of Judgments in Civil Matters between the UK and Norway, which will apply if the UK does not re-accede to the Lugano Convention. The practical effect of this agreement is that judgments will continue to be reciprocally enforceable between the UK and Norway from 1 January 2021.

How should your business act now?

The applicable legal framework for each dispute will depend on the facts of each case. You should review the dispute resolution clauses in your cross-border contracts to assess how they may be affected by Brexit and to seek specialist advice where necessary. You should also seek advice on dispute resolution provisions when entering into new cross-border contracts in 2021.

This week the Interim Injunction Judge of the Netherlands Commercial Court ruled in summary proceedings, following a video hearing, in a case on a EUR 169 million transaction where the plaintiff argued that the final transaction had been concluded and the defendant should proceed with the deal.

This in an – intended – transaction where the letter of intent stipulates that a EUR 30 million break fee is due when no final agreement is signed.

In addition to ruling on this question of construction of an agreement under Dutch law, the judge also had to rule on the break fee if no agreement was concluded and whether it should be amended or reduced because of the current Coronavirus / Covid-19 crisis.

English Language proceedings in a Dutch state court, the Netherlands Commercial Court (NCC)

The case is not just interesting because of the way contract formation is construed under Dutch law and application of concepts of force majeure, unforeseen circumstances and amendment of agreements under the concepts of reasonableness and fairness as well as mitigation of contractual penalties, but also interesting because it was ruled on by a judge of the English language chamber of the Netherlands Commercial Court (NCC).

This new (2019) Dutch state court offers a relatively fast and cost-effective alternative for international commercial litigation, and in particular arbitration, in a neutral jurisdiction with professional judges selected for both their experience in international disputes and their command of English.

The dispute regarding the construction of an M&A agreement under Dutch law in an international setting

The facts are straightforward. Parties (located in New York, USA and the Netherlands) dispute whether final agreement on the EUR 169 million transaction has been reached but do agree a break fee of €30 million in case of non-signature of the final agreement was agreed. However, in addition to claiming there is no final agreement, the defendant also argues that the break fee – due when there is no final agreement – should be reduced or changed due to the coronavirus crisis.

As to contract formation it must be noted that Dutch law allows broad leeway on how to communicate what may or may not be an offer or acceptance. The standard is what a reasonable person in the same circumstances would have understood their communications to mean. Here, the critical fact is that the defendant did not sign the so-called “Transaction Agreement”. The letter of intent’s binary mechanism (either execute and deliver the paperwork for the Transaction Agreement by the agreed date or pay a EUR 30 million fee) may not have been an absolute requirement for contract formation (under Dutch law) but has significant evidentiary weight. In M&A practice – also under Dutch law – with which these parties are thoroughly familiar with, this sets a very high bar for concluding a contract was agreed other than by explicit written agreement. So, parties may generally comfortably rely on what they have agreed on in writing with the assistance of their advisors.

The communications relied on by claimant in this case did not clear the very high bar to assume that despite the mechanism of the letter of intent and the lack of a signed Transaction Agreement there still was a binding agreement. In particular attributing the other party’s advisers’ statements and/or conduct to the contracting party they represent did not work for the claimant in this case as per the verdict nothing suggested that the advisers would be handling everything, including entering into the agreement.

Court order for actual performance of a – deemed – agreement on an M&A deal?

The Interim Injunction Judge finds that there is not a sufficient likelihood of success on the merits so as to justify an interim measure ordering the defendant to actually perform its obligations under the disputed Transaction Agreement (payment of EUR 169 million and take the claimant’s 50% stake in an equestrian show-jumping business).

Enforcement of the break fee despite “Coronavirus”?

Failing the conclusion of an agreement, there was still another question to answer as the letter of intent mechanism re the break fee as such was not disputed. Should the Court enforce the full EUR 30 million fee in the current COVID-19 circumstances? Or should the fee’s effects be modified, mitigated or reduced in some way, or the fee agreement should even be dissolved?

Unforeseen circumstances, reasonableness and fairness

The Interim Injunction Judge rules that the coronavirus crisis may be an unforeseen circumstance, but it is not of such a nature that, according to standards of reasonableness and fairness, the plaintiff cannot expect the break fee obligation to remain unchanged. The purpose of the break fee is to encourage parties to enter into the transaction and attribute / share risks between them. As such the fee limits the exposure of the parties. Payment of the fee is a quick way out of the obligation to pay the purchase price of EUR 169 million and the risks of keeping the target company financially afloat. If financially the coronavirus crisis turns out less disastrous than expected, the fee of EUR 30 million may seem high, but that is what the parties already considered reasonable when they waived their right to invoke the unreasonableness of the fee. The claim for payment of the EUR 30 million break fee is therefore upheld by the Interim Injunction Judge.

Applicable law and the actual practice of it by the courts

The relevant three articles are in this case articles 6:94, 6:248 and 6:258 of the Dutch Civil Code. They relate to the mitigation of contractual penalties, unforeseen circumstances and amendment of the agreement under the tenets of reasonableness and fairness. Under Dutch law the courts must with all three exercise caution. Contracts must generally be enforced as agreed. The parties’ autonomy is deemed paramount and the courts’ attitude is deferential. All three articles use language stating, essentially, that interference by the courts in the contract’s operation is allowed only to avoid an “unacceptable” impact, as assessed under standards of reasonableness and fairness.

There is at this moment of course no well- established case law on COVID-19. However, commentators have provided guidance that is very helpful to think through the issues. Recently a “share the pain” approach has been advocated by a renowned law Professor, Tjittes, who focuses on preserving the parties’ contractual equilibrium in the current circumstances. This is, in the Court’s analysis, the right way to look at the agreement here. There is no evidence in the record suggesting that the parties contemplated or discussed the full and exceptional impact of the COVID-19 crisis. The crisis may or may not be unprovided for. However, the court rules in the current case there is no need to rule on this issue. Even if the crisis is unprovided for, there is no support in the record for the proposition that the crisis makes it unacceptable for the claimant to demand strict performance by the defendant. The reasons are straightforward.

The break fee allocates risk and expresses commitment and caps exposure. The harm to the business may be substantial and structural, or it may be short-term and minimal. Either way, the best “share the pain” solution, to preserve the contractual equilibrium in the agreement, is for the defendant to pay the fee as written in the letter of intent. This allocates a defined risk to one party, and actual or potential risks to the other party. Reducing the break fee in any business downturn, the fee’s express purpose – comfort and confidence to get the deal done – would not be accomplished and be derived in precisely the circumstances in which it should be robust. As a result, the Court therefore orders to pay the full EUR 30 million fee. So the break fee stipulation works under the circumstances without mitigation because of the Corona outbreak.

The Netherlands Commercial Court, continued

As already indicated above, the case is interesting because the verdict has been rendered by a Dutch state court in English and the proceedings where also in English. Not because of a special privilege granted in a specific case but based on an agreement between parties with a proper choice of forum clause for this court. In addition to the benefit to of having an English forum without mandatorily relying on either arbitration or choosing an anglophone court, it also has the benefit of it being a state court with the application of the regular Dutch civil procedure law, which is well known by it’s practitioners and reduces the risk of surprises of a procedural nature. As it is as such also a “normal” state court, there is the right to appeal and particularly effective under Dutch law access to expedited proceeding as was also the case in the example referred to above. This means a regular procedure with full application of all evidentiary rules may still follow, overturning or confirming this preliminary verdict in summary proceedings.

Novel technology in proceedings

Another first or at least a novel application is that all submissions were made in eNCC, a document upload procedure for the NCC. Where the introduction of electronic communication and litigation in the Dutch court system has failed spectacularly, the innovations are now all following in quick order and quite effective. As a consequence of the Coronavirus outbreak several steps have been quickly tried in practice and thereafter formally set up. At present this – finally – includes a secure email-correspondence system between attorneys and the courts.

And, also by special order of the Court in this present case, given the current COVID-19 restrictions the matter was dealt with at a public videoconference hearing on 22 April 2020 and the case was set for judgment on 29 April 2020 and published on 30 April 2020.

Even though it is a novel application, it is highly likely that similar arrangements will continue even after expiry of current emergency measures. In several Dutch courts videoconference hearings are applied on a voluntary basis and is expected that the arrangements will be formalized.

Eligibility of cases for the Netherlands Commercial Court

Of more general interest are the requirements for matters that may be submitted to NCC:

- the Amsterdam District Court or Amsterdam Court of Appeal has jurisdiction

- the parties have expressly agreed in writing that proceedings will be in English before the NCC (the ‘NCC agreement’)

- the action is a civil or commercial matter within the parties’ autonomy

- the matter concerns an international dispute.

The NCC agreement can be recorded in a clause, either before or after the dispute arises. The Court even recommends specific wording:

“All disputes arising out of or in connection with this agreement will be resolved by the Amsterdam District Court following proceedings in English before the Chamber for International Commercial Matters (“Netherlands Commercial Court” or “NCC District Court”), to the exclusion of the jurisdiction of any other courts. An action for interim measures, including protective measures, available under Dutch law may be brought in the NCC’s Court in Summary Proceedings (CSP) in proceedings in English. Any appeals against NCC or CSP judgments will be submitted to the Amsterdam Court of Appeal’s Chamber for International Commercial Matters (“Netherlands Commercial Court of Appeal” or “NCCA”).”

The phrase “to the exclusion of the jurisdiction of any other courts” is included in light of the Hague Convention on Choice of Court Agreements. It is not mandatory to include it of course and parties may decide not to exclude the jurisdiction of other courts or make other arrangements they consider appropriate. The only requirement being that such arrangements comply with the rules of jurisdiction and contract. Please note that choice of court agreements are exclusive unless the parties have “expressly provided” or “agreed” otherwise (as per the Hague Convention and Recast Brussels I Regulation).

Parties in a pending case before another Dutch court or chamber may request that their case be referred to NCC District Court or NCC Court of Appeal. One of the requirements is to agree on a clause that takes the case to the NCC and makes English the language of the proceedings. The NCC recommends using this language:

We hereby agree that all disputes in connection with the case [name parties], which is currently pending at the *** District Court (case number ***), will be resolved by the Amsterdam District Court following proceedings in English before the Chamber for International Commercial Matters (“Netherlands Commercial Court” or ”NCC District Court). Any action for interim measures, including protective measures, available under Dutch law will be brought in the NCC’s Court in Summary Proceedings (CSP) in proceedings in English. Any appeals against NCC or CSP judgments will be submitted to the Amsterdam Court of Appeal’s Chamber for International Commercial Matters (“Netherlands Commercial Court of Appeal” or “NCC Court of Appeal”).

To request a referral, a motion must be made before the other chamber or court where the action is pending, stating the request and contesting jurisdiction (if the case is not in Amsterdam) on the basis of a choice-of-court agreement (see before).

Additional arrangements in the proceedings before the Netherlands Commercial Court

Before or during the proceedings, parties can also agree special arrangements in a customized NCC clause or in another appropriate manner. Such arrangements may include matters such as the following:

- the law applicable to the substantive dispute

- the appointment of a court reporter for preparing records of hearings and the costs of preparing those records

- an agreement on evidence that departs from the general rules

- the disclosure of confidential documents

- the submission of a written witness statement prior to the witness examination

- the manner of taking witness testimony

- the costs of the proceedings.

Visiting lawyers and typical course of the procedure

All acts of process are in principle carried out by a member of the Dutch Bar. Member of the Bar in an EU or EEA Member State or Switzerland may work in accordance with Article 16e of the Advocates Act (in conjunction with a member of the Dutch Bar). Other visiting lawyers may be allowed to speak at any hearing.

The proceedings will typically follow the below steps:

- Submitting the initiating document by the plaintiff (summons or request as per Dutch law)

- Assigned to three judges and a senior law clerk.

- The defendant submits its defence statement.

- Case management conference or motion hearing (e.g. also in respect of preliminary issues such as competence, applicable law etc.) where parties may present their arguments.

- Judgment on motions: the court rules on the motions. Testimony, expert appointment, either at this stage or earlier or later.

- The court may allow the parties to submit further written statements.

- Hearing: the court interviews the parties and allows them to present their arguments. The court may enquire whether the dispute could be resolved amicably and, where appropriate, assist the parties in a settlement process. If appropriate, the court may discuss with the parties whether it would be advisable to submit part or all of the dispute to a mediator. At the end of the hearing, the court will discuss with the parties what the next steps should be.

- Verdict: this may be a final judgment on the claims or an interim judgment ordering one or more parties to produce evidence, allowing the parties to submit written submissions on certain aspects of the case, appointing one or more experts or taking other steps.

Continuous updates, online resources Netherlands Commercial Court

As a final note the English language website of the Netherlands Commercial Court provides ample information on procedure and practical issues and is updated with a high frequence. Under current circumstance even at a higher pace. In particular for practitioners it’s recommended to regularly consult the website. https://www.rechtspraak.nl/English/NCC/Pages/default.aspx

This is a summary of the approved measures, which unfortunately for both tenants and landlords do not include any public aid or tax relief and just refer to a postponement in the payment of the rent.

Premises to which they are applied

Leased premises dedicated to activities different than residential: commercial, professional, industrial, cultural, teaching, amusement, healthcare, etc. They also apply to the lease of a whole industry (i.e. hotels, restaurants, bars, etc., which are the most usual type of businesses object of this deal).

Types of tenants

- Individual entrepreneurs or self-employed persons who were registered before Social Security before the declaration of the state of alarm on March 14th, 2020

- Small and medium companies, as defined by article 257.1 of the Capital Companies Act: those who fulfil during two consecutive fiscal years these figures: assets under € 4 million, turnover under € 8 million and average staff under 50 people

Types of landlords

In order to benefit from these measures, the landlord should be a housing public entity or company or a big owner, considering as such the individuals or companies who own more than 10 urban properties (excluding parking places and storage rooms) or a built surface over 1.500 sqm.

Measures approved

The payment of the rent is postponed without interest meanwhile the state of alarm is in force, but in any case, for a maximum period of four months. Once the state of alarm is overcome, and in any case in a maximum term of four months, the postponed rents should be paid along a maximum period of two years, or the duration of the lease agreement, should it be less than two years.

For landlords different to those mentioned above

The tenant could apply before the landlord for the postponement in the payment of the rent (but the landlord is not obliged to accept it), and the parties can use the guarantee that the tenant should mandatorily have provided at the beginning of any lease agreement (usually equal to two month’s rent, but could be more if agreed by the parties), in full or in part, in order to use it to pay the rent. The tenant will have to provide again the guarantee within one year’s term, or less should the lease agreement have a shorter duration.

Activities to which it is applied

Activities which have been suspended according to the Royal Decree that declared the state of alarm, dated march, 14ht, 2020, or according to the orders issued by the authorities delegated by such Royal Decree. This should be proved through a certificated issued by the tax authorities.

If the activity has not been directly suspended by the Royal Decree, the turnover during the month prior to the postponement should be less than 75% of the average monthly turnover during the same quarter last year. This should be proved through a responsible declaration by the tenant, and the landlord is authorised check the bookkeeping records.

Term to apply and procedure

The tenant should apply for these measures before the landlord within one month’s term from the publication of the Royal Decree-law, that is, from April 22nd, 2020, and the landlord (in case belongs to the groups mentioned in point c) is obliged to accept the tenant’s request, except if both parties have already agreed something different. The postponement would be applied to the following month.

As the state of alarm was declared more than one month ago (March 14th), landlords and tenants have already been reaching some agreements, for example 50% rent reduction during the state of alarm, and 50% rent postponement during the following 6 months. Tenants who do not reach an agreement with the landlord could face an eviction procedure, however court procedures are suspended during the state of alarm. We have also seen some abusive non-payment of rent by tenants.

When is becomes impossible to reach an agreement with the landlord, tenants have the legal remedy of claiming in Court for the application of the “rebus sic stantibus” principle, which was highly demanded during the 2008 financial crisis but very seldom applied by the Courts. This principle is aimed to re-balance the parties’ obligations when their situation had deeply changed because of unforeseen circumstances beyond their control. This principle is not included in the Spanish Civil Code, but the Supreme Court has accepted its application, in a very restricted way, in some occasions.

Écrire à Christophe

Espagne | Rémunération de la clientèle pour les agents et les distributeurs

5 avril 2022

-

Espagne

- Agence

- Contrats

- Distribution

Résumé

Suivons l’histoire de Nike, tirée de la biographie de son fondateur Phil Knight, pour en tirer quelques leçons sur les contrats de distribution internationaux: comment négocier le contrat, établir la durée de l’accord, définir l’exclusivité et les objectifs commerciaux, et déterminer la manière adéquate de résoudre les litiges.

Ce dont je parle dans cet article

- Le conflit entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger et la naissance de Nike

- Comment négocier un accord de distribution international

- L’exclusivité contractuelle dans un accord de distribution commerciale

- Clauses de chiffre d’affaires minimum dans les contrats de distribution

- Durée du contrat et préavis de résiliation

- La propriété des marques dans les contrats de distribution commerciale

- L’importance de la médiation dans les contrats de distribution commerciale internationale

- Clauses de règlement des litiges dans les contrats internationaux

- Comment nous pouvons vous aider

Le différend entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger et la naissance de Nike

Pourquoi la marque de vêtements de sport la plus célèbre au monde est-elle Nike et non Onitsuka Tiger?

Shoe Dog est la biographie du créateur de Nike, Phil Knight: pour les amateurs du genre, mais pas seulement, le livre est vraiment très bon et je recommande sa lecture.

Mû par sa passion pour la course à pied et l’intuition qu’il y avait un espace dans le marché américain des chaussures de sport, à l’époque dominé par Adidas, Knight a été le premier, en 1964, à importer aux États-Unis une marque de chaussures de sport japonaise, Onitsuka Tiger, venant conquérir en 6 ans une part de marché de 70%.

La société fondée par Knight et son ancien entraîneur d’athlétisme universitaire, Bill Bowerman, s’appelait Blue Ribbon Sports.

La relation d’affaires entre Blue Ribbon-Nike et le fabricant japonais Onitsuka Tiger a été, dès le début, très turbulente, malgré le fait que les ventes de chaussures aux États-Unis se déroulaient très bien et que les perspectives de croissance étaient positives.

Lorsque, peu après avoir renouvelé le contrat avec le fabricant japonais, Knight a appris qu’Onitsuka cherchait un autre distributeur aux États-Unis, craignant d’être coupé du marché, il a décidé de chercher un autre fournisseur au Japon et de créer sa propre marque, Nike.

En apprenant le projet Nike, le fabricant japonais a attaqué Blue Ribbon pour violation de l’accord de non-concurrence, qui interdisait au distributeur d’importer d’autres produits fabriqués au Japon, déclarant la résiliation immédiate de l’accord.

À son tour, Blue Ribbon a fait valoir que la violation serait celle d’Onitsuka Tiger, qui avait commencé à rencontrer d’autres distributeurs potentiels alors que le contrat était encore en vigueur et que les affaires étaient très positives.

Cela a donné lieu à deux procès, l’un au Japon et l’autre aux États-Unis, qui auraient pu mettre un terme prématuré à l’histoire de Nike.

Heureusement (pour Nike), le juge américain s’est prononcé en faveur du distributeur et le litige a été clos par un règlement: Nike a ainsi commencé le voyage qui l’amènera 15 ans plus tard à devenir la plus importante marque d’articles de sport au monde.

Comment négocier un accord de distribution commerciale internationale?

Voyons ce que l’histoire de Nike nous apprend et quelles sont les erreurs à éviter dans un contrat de distribution international.

Dans sa biographie, Knight écrit qu‘il a rapidement regretté d’avoir lié l’avenir de son entreprise à un accord commercial de quelques lignes rédigé à la hâte à la fin d’une réunion visant à négocier le renouvellement du contrat de distribution.

Que contenait cet accord?

L’accord prévoyait uniquement le renouvellement du droit de Blue Ribbon de distribuer les produits exclusivement aux Etats-Unis pour trois années supplémentaires.

Il arrive souvent que les contrats de distribution internationale soient confiés à des accords verbaux ou à des contrats très simples et de courte durée: l’explication qui est généralement donnée est qu’il est ainsi possible de tester la relation commerciale, sans trop engager la contrepartie.

Cette façon de faire est cependant erronée et dangereuse: le contrat ne doit pas être considéré comme une charge ou une contrainte, mais comme une garantie des droits des deux parties. Ne pas conclure de contrat écrit, ou le faire de manière très hâtive, signifie laisser sans accords clairs des éléments fondamentaux de la relation future, comme ceux qui ont conduit au litige entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger: objectifs commerciaux, investissements, propriété des marques.

Si le contrat est également international, la nécessité de rédiger un accord complet et équilibré est encore plus forte, étant donné qu’en l’absence d’accords entre les parties, ou en complément de ces accords, on applique une loi avec laquelle l’une des parties n’est pas familière, qui est généralement la loi du pays où le distributeur est basé.