-

Italie

Made in Italy: protection of trademarks of special national interest and value

29 janvier 2025

- Propriété intellectuelle

- Marques et brevets

‘’Made in Italy” is synonymous of high productive and aesthetic quality and represents an added value, in the international market, for different kind of products, from foodstuffs to clothing, automotive and furniture. In recent years, in Italy, a number of initiatives have been taken at the regulatory level to ensure its promotion, valorization and protection.

In 2024 came into force law no. 206/2023, referred to as the ‘New Made in Italy Law’, followed on 3 July 2024 by the related implementing Decree, by which the Ministry of Enterprise and Made in Italy (hereinafter the ‘Ministry’) introduced relevant provisions including the ones related to an official mark attesting the Italian origin of goods, the fight against counterfeiting (in particular in criminal law), and the promotion of the use of blockchain technology to protect production chains.

Among the new measures, there are specific rules for the protection of trademarks – with at least 50 years of registration or use in Italy – of particular national interest and value (hereinafter “Trademark/s”). The aim of such provisions is to safeguard the heritage represented by Italian trademarks with a long-standing presence on the market, preventing their extinction and guaranteeing their use by companies linked to the Italian territory.

Measures to guarantee the continuity

In order to protect the Trademarks, two distinct possibilities are envisaged

- Notification by companies

The first consists of the takeover by the Ministry of the ownership of Trademarks of companies that will cease their activities. In this regard, the Decree provides that a company owner or licensee of a trademark registered for at least 50 years, or for which it is possible to prove continuous use for at least 50 years, intending to cease its activity definitively, must notify the Ministry in advance of the plan to cease its activity, indicating, in particular, the economic, financial or technical reasons that impose the cessation. Upon receipt of this notification, the Ministry is entitled to take over ownership of the trademark without charge if the trademark has not been assigned for consideration by the owner or licensee company.

This procedure, in particular, is newly implemented, being applicable as of 2 December 2024.

- Revocation for non-use

The second possibility concerns Trademarks suspected of not being used for at least 5 years. In such case, the Ministry may file before the Italian Patent and Trademark Office an application for revocation for non-use and, if the application is granted, proceed with registering the Trademark in its name.

Trademarks of national interest owned by the Ministry will be announced on its Web site https://www.mimit.gov.it/it/impresa/competitivita-e-nuove-imprese/proprieta-industriale/marchi-di-interesse-storico/elenco-marchi.

As of 27 January 2025, one month after the applicability of the procedures at issue in the list are the following:

- INNOCENTI – Application number 302023000141171

- AUTOBIANCHI – Application number 302023000141189

Free licences for Italian or foreign companies wishing to invest in Italy

The Ministry is authorized to use the Trademarks, licensing them exclusively in favor of companies, including foreign ones, that intend to invest in Italy or transfer production activities located abroad to Italy.

In particular, Italian and foreign companies planning to produce in Italy may apply for a licence to use the above-mentioned Trademarks. The application shall contain specific details regarding the planned investment project, with a focus on the employment impact of the same.

Should the Ministry accept the application, the company will be granted a 10-year free licence, renewable on condition that the company maintains production activities within the national borders.

It is to be noted that, in the event that the company interrupts its activities or relocates its plants outside the Italian territory, the licence contract may be terminated immediately.

What’s next?

The recent regulatory measures are aimed, on the one hand, at keeping alive traditional brands that have been used in Italy for many years and, on the other hand, at allowing Italian and foreign companies to benefit from the incentive of free licences, if they decide to produce in Italy.

It will be interesting to monitor the business developments of these provisions in the coming months, in which the list of Trademarks owned by the Ministry will become longer.

Summary

Artist Mason Rothschild created a collection of digital images named “MetaBirkins”, each of which depicted a unique image of a blurry faux-fur covered the iconic Hermès bags, and sold them via NFT without any (license) agreement with the French Maison. HERMES brought its trademark action against Rothschild on January 14, 2022.

A Manhattan federal jury of nine persons returned after the trial a verdict stating that Mason Rothschild’s sale of the NFT violated the HERMES’ rights and committed trademark infringement, trademark dilution, and cybersquatting (through the use of the domain name “www.metabirkins.com”) because the US First Amendment protection could not apply in this case and awarded HERMES the following damages: 110.000 US$ as net profit earned by Mason Rothschild and 23.000 US$ because of cybersquatting.

The sale of approx. 100 METABIRKIN NFTs occurred after a broad marketing campaign done by Mason Rothschild on social media.

Rothschild’s defense was that digital images linked to NFT “constitute a form of artistic expression” i.e. a work of art protected under the First Amendment and similar to Andy Wahrhol’s paintings of Campbell’s soup cans. The aim of the defense was to have the “Rogers” legal test (so-called after the case Rogers vs Grimaldi) applied, according to which artists are entitled to use trademarks without permission as long as the work has an artistic value and is not misleading the consumers.

NFTs are digital record (a sort of “digital deed”) of ownership typically recorded in a publicly accessible ledger known as blockchain. Rothschild also commissioned computer engineers to operationalize a “smart contract” for each of the NFTs. A smart contract refers to a computer code that is also stored in the blockchain and that determines the name of each of the NFTs, constrains how they can be sold and transferred, and controls which digital files are associated with each of the NFTs.

The smart contract and the NFT can be owned by two unrelated persons or entities, like in the case here, where Rothschild maintained the ownership of the smart contract but sold the NFT.

“Individuals do not purchase NFTs to own a “digital deed” divorced to any other asset: they buy them precisely so that they can exclusively own the content associated with the NFT” (in this case the digital images of the MetaBirkin”), we can read in the Opinion and Order. The relevant consumers did not distinguish the NFTs offered by Rothschild from the underlying MetaBirkin image associated to the NFT.

The question was whether or not there was a genuine artistic expression or rather an unlawful intent to cash in on an exclusive valuable brand name like HERMES.

Mason Rothschild’s appeal to artistic freedom was not considered grounded since it came out that Rothschild was pursuing a commercial rather than an artistic end, further linking himself to other famous brands: Rothschild remarked that “MetaBirkins NFTs might be the next blue chip”. Insisting that he “was sitting on a gold mine” and referring to himself as “marketing king”, Rothschild “also discussed with his associates further potential future digital projects centered on luxury projects such watch NFTs called “MetaPateks” and linked to the famous Swiss luxury watches Patek Philippe.

TAKE AWAY: This is the first US decision on NFT and IP protection for trademarks.

The debate (i) between the protection of the artistic work and the protection of the trademark or other industrial property rights or (ii) between traditional artistic work and subsequent digital reinterpretation by a third party other than the original author, will lead to other decisions (in Italy, we recall the injunction order issued on 20-7-2022 by the Court of Rome in favour of the Juventus football team against the company Blockeras, producer of NFT associated with collectible digital figurines depicting the footballer Bobo Vieri, without Juventus’ licence or authorisation). This seems to be a similar phenomenon to that which gave rise some 15 years ago to disputes between trademark owners and owners of domain names incorporating those trademarks. For the time being, trademark and IP owners seem to have the upper hand, especially in disputes that seem more commercial than artistic.

For an assessment of the importance and use of NFT and blockchain in association also with IP rights, you can read more here.

In this internet age, the limitless possibilities of reaching customers across the globe to sell goods and services comes the challenge of protecting one’s Intellectual Property Right (IPR). Talking specifically of trademarks, like most other forms of IPR, the registration of a trademark is territorial in nature. One would need a separate trademark filing in India if one intends to protect the trademark in India.

But what type of trademarks are allowed registration in India and what is the procedure and what are the conditions?

The Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (the Registry) is the government body responsible for the administration of trademarks in India. When seeking trademark registration, you will need an address for service in India and a local agent or attorney. The application can be filed online or by paper at the Registry. Based on the originality and uniqueness of the trademark, and subject to opposition or infringement claims by third parties, the registration takes around 18-24 months or even more.

Criteria for adopting and filing a trademark in India

To be granted registration, the trademark should be:

- non-generic

- non-descriptive

- not-identical

- non–deceptive

Trademark Search

It is not mandatory to carry out a trademark search before filing an application. However, the search is recommended so as to unearth conflicting trademarks on file.

How to make the application?

One can consider making a trademark application in the following ways:

- a fresh trademark application through a local agent or attorney;

- application under the Paris Convention: India being a signatory to the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, a convention application can be filed by claiming priority of a previously filed international application. For claiming such priority, the applicant must file a certified copy of the priority document, i.e., the earlier filed international application that forms the basis of claim for priority in India;

- application through the Madrid Protocol: India acceded to the Madrid Protocol in 2013 and it is possible to designate India in an international application.

Objection by the Office – Grounds of Refusal

Within 2-4 months from the date of filing of the trademark application (4-6 months in the case of Madrid Protocol applications), the Registry conducts an examination and sometimes issues an office action/examination report raising objections. The applicant must respond to the Registry within one month. If the applicant fails to respond, the trademark application will be deemed abandoned.

A trademark registration in India can be refused by the Registry for absolute grounds such as (i) the trademark being devoid of any distinctive character (ii) trademark consists of marks that designate the kind, quality, quantity values, geographic origins or time or production of the goods or services (iii) the trademark causes confusion or deceives public. A relative ground for refusal is generally when a trademark is similar or deceptively similar to an earlier trademark.

Objection Hearing

When the Registry is not satisfied with the response, a hearing is scheduled within 8-12 months. During the hearing, the Registry either accepts or rejects the registration.

Publication in TM journal

After acceptance for registration, the trademark will be published in the Trade Marks Journal.

Third Party Opposition

Any person can oppose the trademark within four months of the date of publication in the journal. If there is no opposition within 4-months, the mark would be granted protection by the Registry. An opposition would lead to prosecution proceedings that take around 12-18 months for completion.

Validity of Trademark Registration

The registration dates back to the date of the application and is renewable every 10 years.

“Use of Mark” an important condition for trademark registration

- “First to Use” Rule over “First-to-File” Rule: An application in India can be filed on an “intent to use” basis or by claiming “prior use” of the trademark in India. Unlike other jurisdictions, India follows “first to use” rule over the “first-to-file” rule. This means that the first person who can prove significant use of a trade mark in India will generally have superior rights over a person who files a trade mark application prior but with a later user date or acquires registration prior but with a later user date.

- Spill-over Reputation considered as Use: Given the territorial protection granted for trademarks, the Indian Trademark Law protects the spill-over reputation of overseas trademark even where the trademark has not been used and/or registered in India. This is possible because knowledge of the trademark in India and the reputation acquired through advertisements on television, Internet and publications can be considered as valid proof of use.

Descriptive Marks to acquire distinctiveness to be eligible for registration

Unlike in the US, Indian trademark law does not generally permit registration of a descriptive trademark. A descriptive trademark is a word that identifies the characteristics of the product or service to which the trademark pertains. It is similar to an adjective. An example of descriptive marks is KOLD AND KREAMY for ice cream and CHOCO TREAT in respect of chocolates. However, several courts in India have interpreted that descriptive trademark can be afforded registration if due to its prolonged use in trade it has lost its primary descriptive meaning and has become distinctive in relation to the goods it deals with. Descriptive marks always have to be supported with evidence (preferably from before the date of application for registration) to show that the trademark has acquired a distinctive character as a result of the use made of it or that it was a well-known trademark.

Acquired distinctiveness a criterion for trademark protection

Even if a trademark lacks inherent distinctiveness, it can still be registered if it has acquired distinctiveness through continuous and extensive use. All one has to prove is that before the date of application for registration:

- the trademark has acquired a distinctive character as a result of use;

- established a strong reputation and goodwill in the market; and

- the consumers relate only to the trademark for the respective product or services due to its continuous use.

How can one stop someone from misusing or copying the trademark in India?

An action of passing off or infringement can be taken against someone copying or misusing a trademark.

For unregistered trademarks, a common law action of passing off can be initiated. The passing off of trademarks is a tort actionable under common law and is mainly used to protect the goodwill attached to unregistered trademarks. The owner of the unregistered trademark has to establish its trademark rights by substantiating the trademark’s prior use in India or trans-border reputation in India and prove that the two marks are either identical or similar and there is likelihood of confusion.

For Registered trademarks, a statutory action of infringement can be initiated. The registered proprietor only needs to prove the similarity between the marks and the likelihood of confusion is presumed.

In both the cases, a court may grant relief of injunction and /or monetary compensation for damages for loss of business and /or confiscation or destruction of infringing labels etc. Although registration of trademark is prima facie evidence of validity, registration cannot upstage a prior consistent user of trademark for the rule is ‘priority in adoption prevails over priority in registration’.

Appeals

Any decision of the Registrar of Trademarks can be appealed before the high courts within three months of the Registrar’s order.

It’s thus preferable to have a strategy for protecting trademarks before entering the Indian market. This includes advertising in publications and online media that have circulation and accessibility in India, collating all relevant records evidencing the first use of the mark in India, taking offensive action against the infringing local entity, or considering negotiations depending upon the strength of the foreign mark and the transborder reputation it carries.

Résumé

Suivons l’histoire de Nike, tirée de la biographie de son fondateur Phil Knight, pour en tirer quelques leçons sur les contrats de distribution internationaux: comment négocier le contrat, établir la durée de l’accord, définir l’exclusivité et les objectifs commerciaux, et déterminer la manière adéquate de résoudre les litiges.

Ce dont je parle dans cet article

- Le conflit entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger et la naissance de Nike

- Comment négocier un accord de distribution international

- L’exclusivité contractuelle dans un accord de distribution commerciale

- Clauses de chiffre d’affaires minimum dans les contrats de distribution

- Durée du contrat et préavis de résiliation

- La propriété des marques dans les contrats de distribution commerciale

- L’importance de la médiation dans les contrats de distribution commerciale internationale

- Clauses de règlement des litiges dans les contrats internationaux

- Comment nous pouvons vous aider

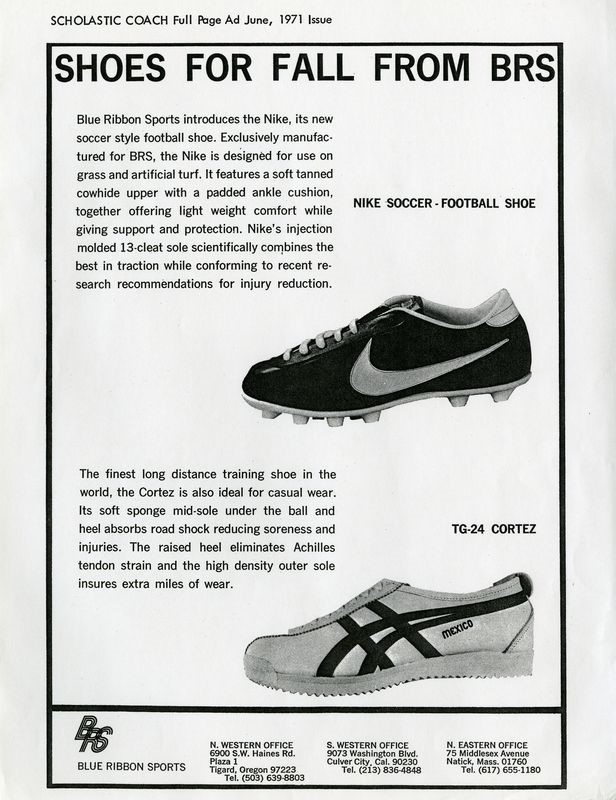

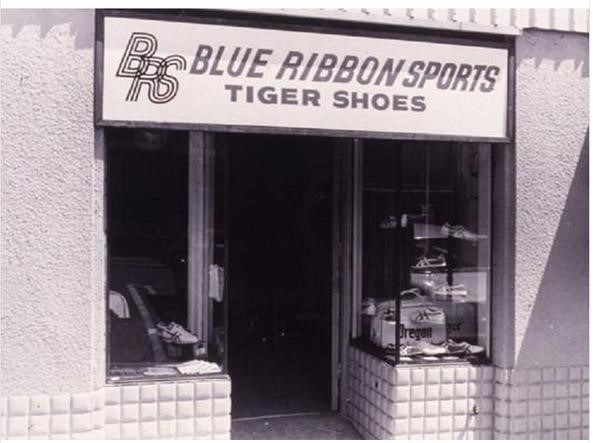

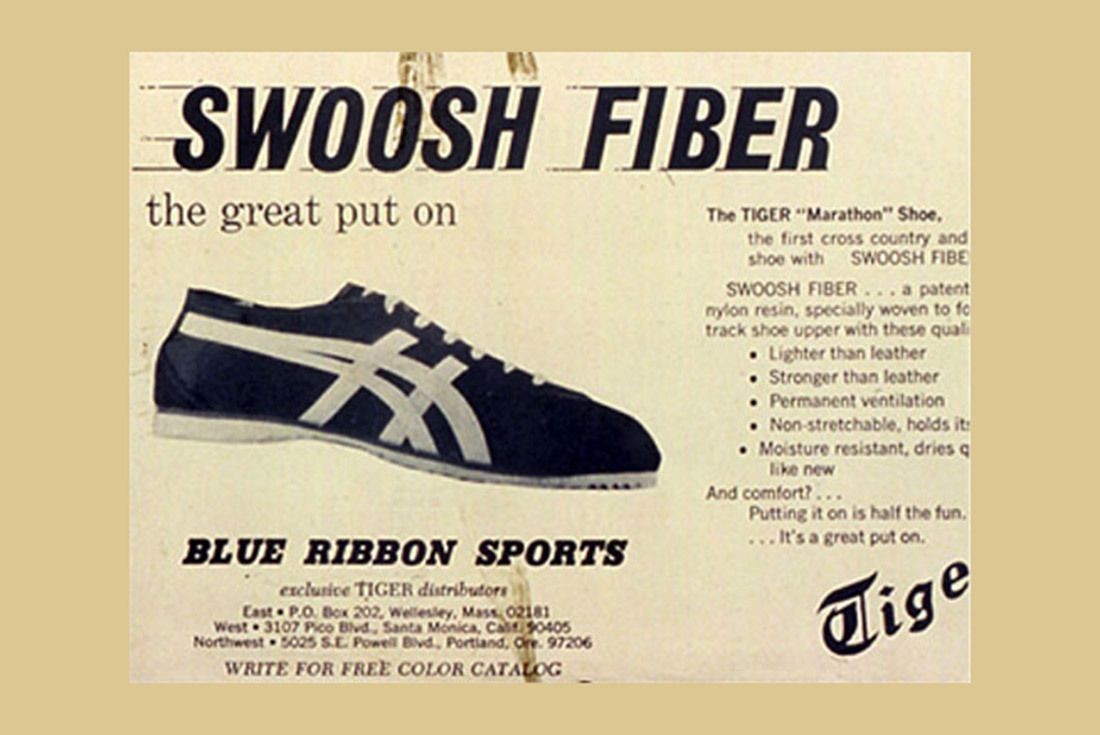

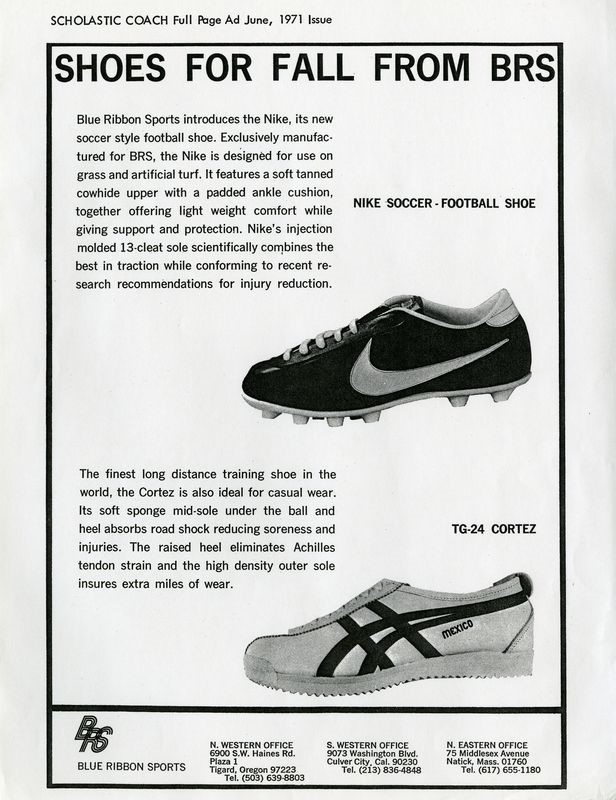

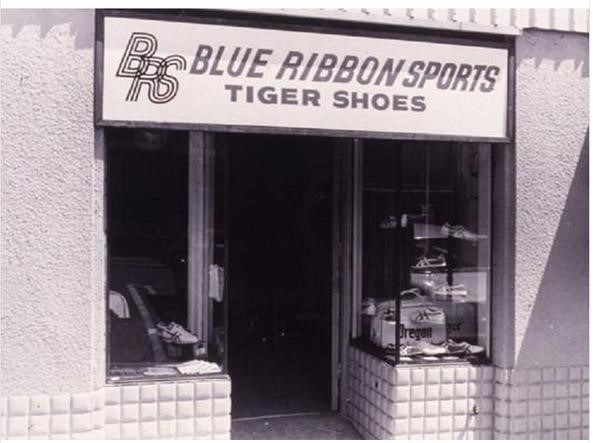

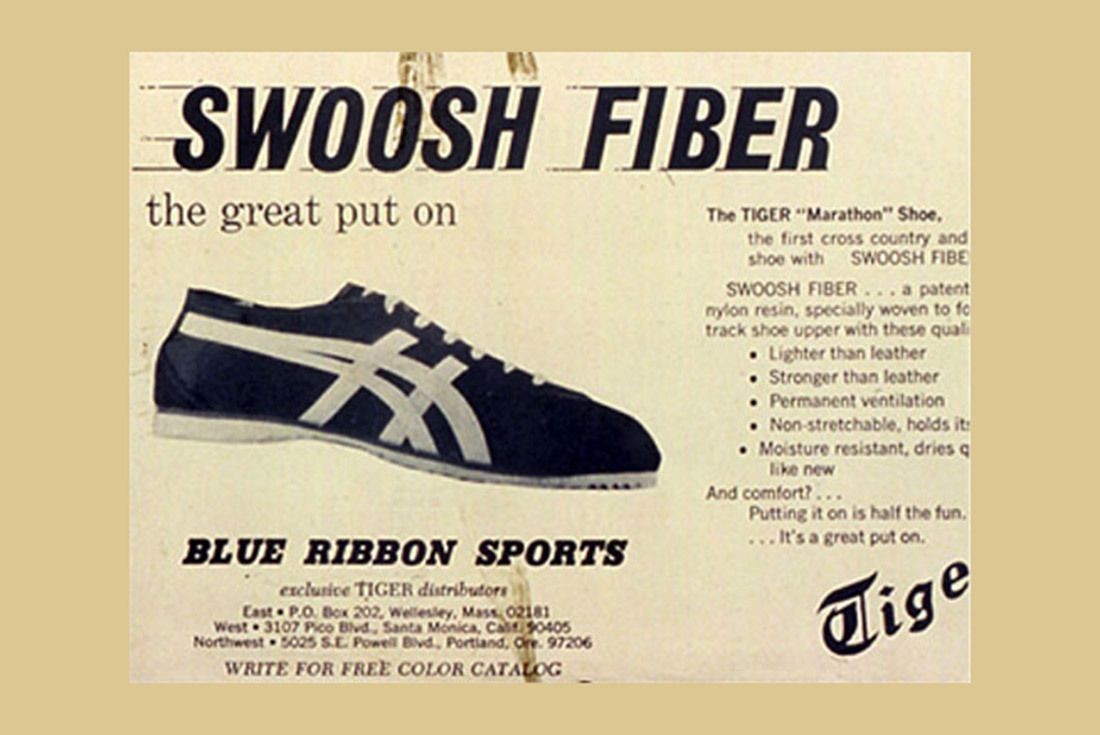

Le différend entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger et la naissance de Nike

Pourquoi la marque de vêtements de sport la plus célèbre au monde est-elle Nike et non Onitsuka Tiger?

Shoe Dog est la biographie du créateur de Nike, Phil Knight: pour les amateurs du genre, mais pas seulement, le livre est vraiment très bon et je recommande sa lecture.

Mû par sa passion pour la course à pied et l’intuition qu’il y avait un espace dans le marché américain des chaussures de sport, à l’époque dominé par Adidas, Knight a été le premier, en 1964, à importer aux États-Unis une marque de chaussures de sport japonaise, Onitsuka Tiger, venant conquérir en 6 ans une part de marché de 70%.

La société fondée par Knight et son ancien entraîneur d’athlétisme universitaire, Bill Bowerman, s’appelait Blue Ribbon Sports.

La relation d’affaires entre Blue Ribbon-Nike et le fabricant japonais Onitsuka Tiger a été, dès le début, très turbulente, malgré le fait que les ventes de chaussures aux États-Unis se déroulaient très bien et que les perspectives de croissance étaient positives.

Lorsque, peu après avoir renouvelé le contrat avec le fabricant japonais, Knight a appris qu’Onitsuka cherchait un autre distributeur aux États-Unis, craignant d’être coupé du marché, il a décidé de chercher un autre fournisseur au Japon et de créer sa propre marque, Nike.

En apprenant le projet Nike, le fabricant japonais a attaqué Blue Ribbon pour violation de l’accord de non-concurrence, qui interdisait au distributeur d’importer d’autres produits fabriqués au Japon, déclarant la résiliation immédiate de l’accord.

À son tour, Blue Ribbon a fait valoir que la violation serait celle d’Onitsuka Tiger, qui avait commencé à rencontrer d’autres distributeurs potentiels alors que le contrat était encore en vigueur et que les affaires étaient très positives.

Cela a donné lieu à deux procès, l’un au Japon et l’autre aux États-Unis, qui auraient pu mettre un terme prématuré à l’histoire de Nike.

Heureusement (pour Nike), le juge américain s’est prononcé en faveur du distributeur et le litige a été clos par un règlement: Nike a ainsi commencé le voyage qui l’amènera 15 ans plus tard à devenir la plus importante marque d’articles de sport au monde.

Comment négocier un accord de distribution commerciale internationale?

Voyons ce que l’histoire de Nike nous apprend et quelles sont les erreurs à éviter dans un contrat de distribution international.

Dans sa biographie, Knight écrit qu‘il a rapidement regretté d’avoir lié l’avenir de son entreprise à un accord commercial de quelques lignes rédigé à la hâte à la fin d’une réunion visant à négocier le renouvellement du contrat de distribution.

Que contenait cet accord?

L’accord prévoyait uniquement le renouvellement du droit de Blue Ribbon de distribuer les produits exclusivement aux Etats-Unis pour trois années supplémentaires.

Il arrive souvent que les contrats de distribution internationale soient confiés à des accords verbaux ou à des contrats très simples et de courte durée: l’explication qui est généralement donnée est qu’il est ainsi possible de tester la relation commerciale, sans trop engager la contrepartie.

Cette façon de faire est cependant erronée et dangereuse: le contrat ne doit pas être considéré comme une charge ou une contrainte, mais comme une garantie des droits des deux parties. Ne pas conclure de contrat écrit, ou le faire de manière très hâtive, signifie laisser sans accords clairs des éléments fondamentaux de la relation future, comme ceux qui ont conduit au litige entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger: objectifs commerciaux, investissements, propriété des marques.

Si le contrat est également international, la nécessité de rédiger un accord complet et équilibré est encore plus forte, étant donné qu’en l’absence d’accords entre les parties, ou en complément de ces accords, on applique une loi avec laquelle l’une des parties n’est pas familière, qui est généralement la loi du pays où le distributeur est basé.

Même si vous n’êtes pas dans la situation du Blue Ribbon, où il s’agissait d’un accord dont dépendait l’existence même de l’entreprise, les contrats internationaux doivent être discutés et négociés avec l’aide d’un avocat expert qui connaît la loi applicable à l’accord et peut aider l’entrepreneur à identifier et à négocier les clauses importantes du contrat.

Exclusivité territoriale, objectifs commerciaux et objectifs minimaux de chiffre d’affaires

La première raison du conflit entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger était l’évaluation de l’évolution des ventes sur le marché américain.

Onitsuka soutenait que le chiffre d’affaires était inférieur au potentiel du marché américain, alors que selon Blue Ribbon la tendance des ventes était très positive, puisque jusqu’à ce moment-là elle avait doublé chaque année le chiffre d’affaires, conquérant une part importante du secteur du marché.

Lorsque Blue Ribbon a appris qu’Onituska évaluait d’autres candidats pour la distribution de ses produits aux États-Unis et craignant d’être bientôt exclu du marché, Blue Ribbon a préparé la marque Nike comme plan B: lorsque cela a été découvert par le fabricant japonais, la situation s’est précipitée et a conduit à un différend juridique entre les parties.

Ce litige aurait peut-être pu être évité si les parties s’étaient mises d’accord sur des objectifs commerciaux et si le contrat avait inclus une clause assez classique dans les accords de distribution exclusive, à savoir un objectif de vente minimum de la part du distributeur.

Dans un accord de distribution exclusive, le fabricant accorde au distributeur une forte protection territoriale contre les investissements que le distributeur réalise pour développer le marché attribué.

Afin d’équilibrer la concession de l’exclusivité, il est normal que le producteur demande au distributeur ce que l’on appelle le chiffre d’affaires minimum garanti ou l’objectif minimum, qui doit être atteint par le distributeur chaque année afin de maintenir le statut privilégié qui lui est accordé.

Si l’objectif minimum n’est pas atteint, le contrat prévoit généralement que le fabricant a le droit de se retirer du contrat (dans le cas d’un accord à durée indéterminée) ou de ne pas le renouveler (si le contrat est à durée déterminée) ou de révoquer ou de restreindre l’exclusivité territoriale.

Dans le contrat entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger, l’accord ne prévoyait aucun objectif (et en fait, les parties n’étaient pas d’accord sur l’évaluation des résultats du distributeur) et venait d’être renouvelé pour trois ans: comment peut-on prévoir des objectifs de chiffre d’affaires minimum dans un contrat pluriannuel?

En l’absence de données fiables, les parties s’appuient souvent sur des mécanismes d’augmentation en pourcentage prédéterminés: +10% la deuxième année, +30% la troisième, +50% la quatrième, et ainsi de suite.

Le problème de cet automatisme est que les objectifs sont convenus sans disposer des données réelles sur l’évolution future des ventes du produit, des ventes des concurrents et du marché en général, et peuvent donc être très éloignés des possibilités actuelles de vente du distributeur.

Par exemple, contester le distributeur pour ne pas avoir atteint l’objectif de la deuxième ou troisième année dans une économie en récession serait certainement une décision discutable et une source probable de désaccord.

Il serait préférable de prévoir une clause de fixation consensuelle des objectifs d’une année sur l’autre, stipulant que les objectifs seront convenus entre les parties à la lumière des performances de vente des mois précédents, avec un certain préavis avant la fin de l’année en cours.

En cas d’absence d’accord sur le nouvel objectif, le contrat peut prévoir l’application de l’objectif de l’année précédente ou le droit pour les parties de se retirer, moyennant un certain délai de préavis.

D’autre part, il ne faut pas oublier que l’objectif peut également être utilisé comme une incitation pour le distributeur: il peut être prévu, par exemple, que si un certain chiffre d’affaires est atteint, cela permettra de renouveler l’accord, de prolonger l’exclusivité territoriale ou d’obtenir certaines compensations commerciales pour l’année suivante.

Une dernière recommandation est de gérer correctement la clause d’objectif minimum, si elle est présente dans le contrat: il arrive souvent que le fabricant conteste la non-atteinte de l’objectif pour une certaine année, après une longue période pendant laquelle les objectifs annuels n’avaient pas été atteints, ou n’avaient pas été actualisés, sans aucune conséquence.

Dans ce cas, il est possible que le distributeur invoque une renonciation implicite à cette protection contractuelle et donc que la rétractation ne soit pas valable: pour éviter les litiges à ce sujet, il est conseillé de prévoir expressément dans la clause Minimum Target que le fait de ne pas contester la non-atteinte de l’objectif pour une certaine période ne signifie pas que l’on renonce au droit d’activer la clause dans le futur.

Le délai de préavis pour la résiliation d’un contrat de distribution internationale

L’autre litige entre les parties concernait la violation d’un accord de non-concurrence: la vente de la marque Nike par Blue Ribbon, alors que le contrat interdisait la vente d’autres chaussures fabriquées au Japon.

Onitsuka Tiger a affirmé que Blue Ribbon avait violé l’accord de non-concurrence, tandis que le distributeur a estimé qu’il n’avait pas d’autre choix, étant donné la décision imminente du fabricant de résilier l’accord.

Ce type de litige peut être évité en fixant clairement une période de préavis pour la résiliation (ou le non-renouvellement): cette période a pour fonction fondamentale de permettre aux parties de se préparer à la fin de la relation et d’organiser leurs activités après la résiliation.

En particulier, afin d’éviter des malentendus tels que celui qui s’est produit entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger, on peut prévoir que, pendant cette période, les parties pourront prendre contact avec d’autres distributeurs et producteurs potentiels, et que cela ne viole pas les obligations d’exclusivité et de non-concurrence.

Dans le cas de Blue Ribbon, en effet, le distributeur avait fait un pas de plus que la simple recherche d’un autre fournisseur, puisqu’il avait commencé à vendre des produits Nike alors que le contrat avec Onitsuka était encore valide: ce comportement représente une grave violation d’un accord d’exclusivité.

Un aspect particulier à prendre en considération concernant le délai de préavis est sa durée: quelle doit être la durée du préavis pour être considéré comme équitable ? Dans le cas de relations commerciales de longue date, il est important de donner à l’autre partie suffisamment de temps pour se repositionner sur le marché, en cherchant d’autres distributeurs ou fournisseurs, ou (comme dans le cas de Blue Ribbon/Nike) pour créer et lancer sa propre marque.

L’autre élément à prendre en compte, lors de la communication de la résiliation, est que le préavis doit être tel qu’il permette au distributeur d’amortir les investissements réalisés pour remplir ses obligations pendant le contrat; dans le cas de Blue Ribbon, le distributeur, à la demande expresse du fabricant, avait ouvert une série de magasins monomarques tant sur la côte ouest que sur la côte est des États-Unis.

Une clôture du contrat peu après son renouvellement et avec un préavis trop court n’aurait pas permis au distributeur de réorganiser le réseau de vente avec un produit de remplacement, obligeant la fermeture des magasins qui avaient vendu les chaussures japonaises jusqu’à ce moment.

En général, il est conseillé de prévoir un délai de préavis pour la résiliation d’au moins 6 mois, mais dans les contrats de distribution internationale, il faut prêter attention, en plus des investissements réalisés par les parties, aux éventuelles dispositions spécifiques de la loi applicable au contrat (ici, par exemple, une analyse approfondie pour la résiliation brutale des contrats en France) ou à la jurisprudence en matière de rupture des relations commerciales (dans certains cas, le délai considéré comme approprié pour un contrat de concession de vente à long terme peut atteindre 24 mois).

Enfin, il est normal qu’au moment de la clôture du contrat, le distributeur soit encore en possession de stocks de produits: cela peut être problématique, par exemple parce que le distributeur souhaite généralement liquider le stock (ventes flash ou ventes via des canaux web avec de fortes remises) et cela peut aller à l’encontre des politiques commerciales du fabricant et des nouveaux distributeurs.

Afin d’éviter ce type de situation, une clause qui peut être incluse dans le contrat de distribution est celle relative au droit du producteur de racheter le stock existant à la fin du contrat, en fixant déjà le prix de rachat (par exemple, égal au prix de vente au distributeur pour les produits de la saison en cours, avec une remise de 30% pour les produits de la saison précédente et avec une remise plus importante pour les produits vendus plus de 24 mois auparavant).

Propriété de la marque dans un accord de distribution international

Au cours de la relation de distribution, Blue Ribbon avait créé un nouveau type de semelle pour les chaussures de course et avait inventé les marques Cortez et Boston pour les modèles haut de gamme de la collection, qui avaient connu un grand succès auprès du public, gagnant une grande popularité: à la fin du contrat, les deux parties ont revendiqué la propriété des marques.

Des situations de ce type se produisent fréquemment dans les relations de distribution internationale: le distributeur enregistre la marque du fabricant dans le pays où il opère, afin d’empêcher les concurrents de le faire et de pouvoir protéger la marque en cas de vente de produits contrefaits ; ou bien il arrive que le distributeur, comme dans le litige dont nous parlons, collabore à la création de nouvelles marques destinées à son marché.

À la fin de la relation, en l’absence d’un accord clair entre les parties, un litige peut survenir comme celui de l’affaire Nike: qui est le propriétaire, le producteur ou le distributeur?

Afin d’éviter tout malentendu, le premier conseil est d’enregistrer la marque dans tous les pays où les produits sont distribués, et pas seulement: dans le cas de la Chine, par exemple, il est conseillé de l’enregistrer quand même, afin d’éviter que des tiers de mauvaise foi ne s’approprient la marque (pour plus d’informations, voir ce billet sur Legalmondo).

Il est également conseillé d’inclure dans le contrat de distribution une clause interdisant au distributeur de déposer la marque (ou des marques similaires) dans le pays où il opère, en prévoyant expressément le droit pour le fabricant de demander son transfert si tel était le cas.

Une telle clause aurait empêché la naissance du litige entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger.

Les faits que nous relatons datent de 1976: aujourd’hui, en plus de clarifier la propriété de la marque et les modalités d’utilisation par le distributeur et son réseau de vente, il est conseillé que le contrat réglemente également l’utilisation de la marque et des signes distinctifs du fabricant sur les canaux de communication, notamment les médias sociaux.

Il est conseillé de stipuler clairement que le fabricant est le propriétaire des profils de médias sociaux, des contenus créés et des données générées par l’activité de vente, de marketing et de communication dans le pays où opère le distributeur, qui ne dispose que de la licence pour les utiliser, conformément aux instructions du propriétaire.

En outre, il est bon que l’accord établisse la manière dont la marque sera utilisée et les politiques de communication et de promotion des ventes sur le marché, afin d’éviter des initiatives qui pourraient avoir des effets négatifs ou contre-productifs.

La clause peut également être renforcée en prévoyant des pénalités contractuelles dans le cas où, à la fin du contrat, le distributeur refuserait de transférer le contrôle des canaux numériques et des données générées dans le cadre de l’activité commerciale.

La médiation dans les contrats de distribution commerciale internationale

Un autre point intéressant offert par l’affaire Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger est lié à la gestion des conflits dans les relations de distribution internationale: des situations telles que celle que nous avons vue peuvent être résolues efficacement par le recours à la médiation.

C’est une tentative de conciliation du litige, confiée à un organisme spécialisé ou à un médiateur, dans le but de trouver un accord amiable qui évite une action judiciaire.

La médiation peut être prévue dans le contrat comme une première étape, avant l’éventuel procès ou arbitrage, ou bien elle peut être initiée volontairement dans le cadre d’une procédure judiciaire ou arbitrale déjà en cours.

Les avantages sont nombreux: le principal est la possibilité de trouver une solution commerciale qui permette la poursuite de la relation, au lieu de chercher uniquement des moyens de mettre fin à la relation commerciale entre les parties.

Un autre aspect intéressant de la médiation est celui de surmonter les conflits personnels: dans le cas de Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka, par exemple, un élément décisif dans l’escalade des problèmes entre les parties était la relation personnelle difficile entre le PDG de Blue Ribbon et le directeur des exportations du fabricant japonais, aggravée par de fortes différences culturelles.

Le processus de médiation introduit une troisième figure, capable de dialoguer avec les parties et de les guider dans la recherche de solutions d’intérêt mutuel, qui peut être décisive pour surmonter les problèmes de communication ou les hostilités personnelles.

Pour ceux qui sont intéressés par le sujet, nous vous renvoyons à ce post sur Legalmondo et à la rediffusion d’un récent webinaire sur la médiation des conflits internationaux.

Clauses de règlement des différends dans les accords de distribution internationaux

Le litige entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger a conduit les parties à engager deux procès parallèles, l’un aux États-Unis (initié par le distributeur) et l’autre au Japon (enraciné par le fabricant).

Cela a été possible parce que le contrat ne prévoyait pas expressément la manière dont les litiges futurs seraient résolus, générant ainsi une situation très compliquée, de plus sur deux fronts judiciaires dans des pays différents.

Les clauses qui établissent la loi applicable à un contrat et la manière dont les litiges doivent être résolus sont connues sous le nom de « clauses de minuit », car elles sont souvent les dernières clauses du contrat, négociées tard dans la nuit.

Ce sont, en fait, des clauses très importantes, qui doivent être définies de manière consciente, afin d’éviter des solutions inefficaces ou contre-productives.

Comment nous pouvons vous aider

La construction d’un accord de distribution commerciale internationale est un investissement important, car il fixe les règles de la relation entre les parties pour l’avenir et leur fournit les outils pour gérer toutes les situations qui seront créées dans la future collaboration.

Il est essentiel non seulement de négocier et de conclure un accord correct, complet et équilibré, mais aussi de savoir le gérer au fil des années, surtout lorsque des situations de conflit se présentent.

Legalmondo offre la possibilité de travailler avec des avocats expérimentés dans la distribution commerciale internationale dans plus de 60 pays: écrivez-nous vos besoins.

Summary – The company that incurs into a counterfeiting of its Community design shall not start as many disputes as are the countries where the infringement has been carried out: it will be sufficient to start a lawsuit in just one court of the Union, in its capacity as Community design court, and get a judgement against a counterfeiter enforceable in different, or even all, Countries of the European Union.

Italian companies are famous all over the world thanks to their creative abilities regarding both industrial inventions and design: in fact, they often make important economic investments in order to develop innovative solutions for the products released on the market.

Such investments, however, must be effectively protected against cases of counterfeiting that, unfortunately, are widely spread and ever more realizable thanks to the new technologies such as the e-commerce. Companies must be very careful in protecting their own products, at least in the whole territory of the European Union, since counterfeiting inevitably undermines the efforts made for the research of an original product.

In this respect the content of a recent judgement issued by the Court of Milan, section specialized in business matters, No. 2420/2020, appears very significant since it shows that it is possible and necessary, in case of counterfeiting (in this case the matter is the counterfeiting of a Community design) to promptly take a legal action, that is to start a lawsuit to the competent Court specialized in business matters.

The Court, by virtue of the EU Regulation No. 6/2002, will issue an order (an urgent and protective remedy ante causam or a judgement at the end of the case) effective in the whole European territory so preventing any extra UE counterfeiter from marketing, promoting and advertising a counterfeited product.

The Court of Milan, in this specific case, had to solve a dispute aroused between an Italian company producing a digital flowmeter, being the subject of a Community registration, and a competitor based in Hong Kong. The Italian company alleged that the latter had put on the European market some flow meters in infringement of a Community design held by the first.

First of all, the panel of judges effected a comparison between the Community design held by the Italian company (plaintiff) and the flow meter manufactured and distributed by the Hong Kong company (defendant). The judges noticed that the latter actually coincided both for dimensions and proportions with the first so that even an expert in the field (the so-called informed user) could mistake the product of the defendant company with that of the plaintiff company owner of the Community design.

The Court of Milan, in its capacity as Community designs court, after ascertaining the counterfeiting, in the whole European territory, carried out by the defendant at the expense of the plaintiff, with judgement No. 2420/2020 prohibited, by virtue of articles 82, 83 and 89 of the EU Regulation No. 6/2002, the Hong Kong company to publicize, offer for sale, import and market, by any means and methods, throughout the European Union, even through third parties, the flow meter subject to the present judgement, with any name if presenting similar characteristics.

The importance of this judgement lies in its effects spread all over the territory of the European Union. This is not a small thing since the company that incurs into a counterfeiting of its Community design shall not start as many disputes as are the countries where the infringement has been carried out: it will be sufficient for this company to start a lawsuit in just one court of the Union, in its capacity as Community design court, and get a judgement against a counterfactor who makes an illicit in different, or even all, Countries of the European Union.

Said judgement will be even more effective if we consider that, by virtue of the UE Customs Regulation No. 608/2013, the company will be able to communicate the existence of a counterfeited product to the customs of the whole European territory (through a single request filed with the customs with the territorial jurisdiction) in order to have said products blocked and, in case, destroyed.

Summary – What can the owner (or licensee) of a trademark do if an unauthorized third party resells products with its trademark on an online platform? This issue was addressed in the judgment of C-567/18 of 2 April 2020, in which the Court of Justice of the European Union confirmed that platforms (Amazon Marketplace, in this case) storing goods which infringe trademark rights are not liable for such infringement, unless the platform puts them on the market or is aware of the infringement. Conversely, platforms (such as Amazon Retail) that contribute to the distribution or resell the products themselves may be liable.

Background

Coty – a German company, distributor of perfumes, holding a licence for the EU trademark “Davidoff” – noted that third-party sellers were offering on Amazon Marketplace perfumes bearing the « Davidoff Hot Water » brand, which had been put in the EU market without its consent.

After reaching an agreement with one of the sellers, Coty sued Amazon in order to prevent it from storing and shipping those perfumes unless they were placed on the EU market with Coty’s consent. Both the Court of First Instance and the Court of Appeal rejected Coty’s request, which brought an appeal before the German Court of Cassation, which in turn referred the matter to the Court of Justice of the EU.

What is the Exhaustion of the rights conferred by a trademark

The principle of exhaustion is envisaged by EU law, according to which, once a good is put on the EU market, the proprietor of the trademark right on that specific good can no longer limit its use by third parties.

This principle is effective only if the entry of the good (the reference is to the individual product) on the market is done directly by the right holder, or with its consent (e.g. through an operator holding a licence).

On the contrary, if the goods are placed on the market by third parties without the consent of the proprietor, the latter may – by exercising the trademark rights established by art. 9, par. 3 of EU Regulation 2017/1001 – prohibit the use of the trademark for the marketing of the products.

By the legal proceedings which ended before the Court of Justice of the EU, Coty sought to enforce that right also against Amazon, considering it to be a user of the trademark, and therefore liable for its infringement.

What is the role of Amazon?

The solution of the case revolves around the role of the web platform.

Although Amazon provides users with a unique search engine, it hosts two radically different sales channels. Through the Amazon Retail channel, the customer buys products directly from the Amazon company, which operates as a reseller of products previously purchased from third party suppliers.

The Amazon Marketplace, on the other hand, displays products owned by third-party vendors, so purchase agreements are concluded between the end customer and the vendor. Amazon gets a commission on these transactions, while the vendor assumes the responsibility for the sale and can manage the prices of the products independently.

According to the German courts which rejected Coty’s claims in the first and second instance, Amazon Marketplace essentially acts as a depository, without offering the goods for sale or putting them on the market.

Coty, vice versa, argues that Amazon Marketplace, by offering various marketing-services (including: communication with potential customers in order to sell the products; provision of the platform through which customers conclude the contract; and consistent promotion of the products, both on its website and through advertisements on Google), can be considered as a « user » of the trademark, within the meaning of Article 9, paragraph 3 of EU Regulation 2017/1001.

The decision of the Court of Justice of the European Union

Advocate General Campos Sanchez-Bordona, in the opinion delivered on 28 November 2019, had suggested to the Court to distinguish between: the mere depositaries of the goods, not to be considered as « users » of the trademark for the purposes of EU Regulation 2017/1001; and those who – in addition to providing the deposit service – actively participate in the distribution of the goods. These latter, in the light of art. 9, par. 3, letter b) of EU Regulation 2017/1001, should be considered as « users » of the trademark, and therefore directly responsible in case of infringements.

The Bundesgerichtshof (Federal Court of Justice of Germany), however, had already partially answered the question when it referred the matter to the European Court, stating that Amazon Marketplace “merely stored the goods concerned, without offering them for sale or putting them on the market”, both operations carried out solely by the vendor.

The EU Court of Justice ruled the case on the basis of some precedents, in which it had already stated that:

- The expression “using” involves at the very least, the use of the sign in the commercial communication. A person may thus allow its clients to use signs which are identical or similar to trademarks without itself using those signs (see Google vs Louis Vuitton, Joined Cases C-236/08 to C-238/08, par. 56).

- With regard to e-commerce platforms, the use of the sign identical or similar to a trademark is made by the sellers, and not by the platform operator (see L’Oréal vs eBay, C‑324/09, par. 103).

- The service provider who simply performs a technical part of the production process cannot be qualified as a « user » of any signs on the final products. (see Frisdranken vs Red Bull, C‑119/10, par. 30. Frisdranken is an undertaking whose main activity is filling cans, supplied by a third party, already bearing signs similar to Redbull’s registered trademarks).

On the basis of that case-law and the qualification of Amazon Marketplace provided by the referring court, the European Court has ruled that a company which, on behalf of a third party, stores goods which infringe trademark rights, if it is not aware of that infringement and does not offer them for sale or place them on the market, is not making “use” of the trademark and, therefore, is not liable to the proprietor of the rights to that trademark.

Conclusion

After Coty had previously been the subject of a historic ruling on the matter (C-230/16 – link to the Legalmondo previous post), in this case the Court of Justice decision confirmed the status quo, but left the door open for change in the near future.

A few considerations on the judgement, before some practical tips:

- The Court did not define in positive terms the criteria for assessing whether an online platform performs sufficient activity to be considered as a user of the sign (and therefore liable for any infringement of the registered trademark). This choice is probably dictated by the fact that the criteria laid down could have been applied (including to the various companies belonging to the Amazon group) in a non-homogeneous manner by the various Member States’ national courts, thus jeopardising the uniform application of European law.

- If the Court of Justice had decided the case the other way around, the ruling would have had a disruptive impact not only on Amazon’s Marketplace, but on all online operators, because it would have made them directly responsible for infringements of IP rights by third parties.

- If the perfumes in question had been sold through Amazon Retail, there would have been no doubt about Amazon’s responsibility: through this channel, sales are concluded directly between Amazon and the end customer.

- The Court has not considered whether: (i) Amazon could be held indirectly liable within the meaning of Article 14(1) of EU Directive 2000/31, as a “host” which – although aware of the illegal activity – did not prevent it; (ii) under Article 11 of EU Directive 2004/48, Coty could have acted against Amazon as an intermediary whose services are used by third parties to infringe its IP right. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that Amazon may be held (indirectly) liable for the infringements committed, including on the Marketplace: this aspect will have to be examined in detail on a case-by-case basis.

Practical tips

What can the owner (or licensee) of a trademark do if an unauthorized third party resells products with its trademark on an online platform?

- Gather as much evidence as possible of the infringement in progress: the proof of the infringement is one of the most problematic aspects of IP litigation.

- Contact a specialized lawyer to send a cease-and-desist letter to the unauthorized seller, ordering the removal of the products from the platform and asking the compensation for damages suffered.

- If the products are not removed from the marketplace, the trademark owner might take legal action to obtain the removal of the products and compensation for damages.

- In light of the judgment in question, the online platforms not playing an active role in the resale of goods remain not directly responsible for IP violations. Nevertheless, it is suggested to consider sending the cease-and-desist letter to them as well, in order to put more pressure on the unauthorised seller.

- The sending of the cease-and-desist letter also to the platform – especially in the event of several infringements – may also be useful to demonstrate its (indirect) liability for lack of vigilance, as seen in point 4) of the above list.

Quick summary – Poland has recently introduced tax incentives which aim at promoting innovations and technology. The new support instrument for investors conducting R&D activity is named «IP Box» and allows for a preferential taxation of qualified profits made on commercialization of several types of qualified property rights. The preferential income tax rate amounts to 5%. By contrast, the general rate is in most cases 19%.

The Qualified Intellectual Property Rights

The intellectual property rights which may be the source of the qualified profit subject the preferential taxation are the following:

- rights to an invention (patents)

- additional protective rights for an invention

- rights for the utility model

- rights from the registration of an industrial design

- rights from registration of the integrated circuit topography

- additional protection rights for a patent for medicinal product or plant protection product

- rights from registration of medicinal or veterinary product

- rights from registration of new plant varieties and animal breeds, and

- rights to a computer program

The above catalogue of qualified intellectual property rights is exhaustive.

Conditions for the application of the Patent Box

A taxpayer may apply the preferential 5% rate on the condition that he or she has created, developed or improved these rights in the course of his/her R&D activities. A taxpayer may create intellectual property but it may also purchase or license it on the exclusive basis, provided that the taxpayer then incurs costs related to the development or improvement of the acquired right.

For example an IT company may create a computer program itself within its R&D activity or it may acquire it from a third party and develop it further. Future income received as a result of commercialization of this computer program may be subject to the tax relief.

The following kinds of income may be subject to tax relief:

- fees or charges arising from the license for qualified intellectual property rights

- the sale of qualified intellectual property rights

- qualified intellectual property rights included in the sale price of the products or services

- the compensation for infringement of qualified intellectual property rights if obtained in litigation proceedings, including court proceedings or arbitration.

How to calculate the tax base

The preferential tax rate is 5% on the tax base. The latter is calculated according to a special formula: the total income received from a particular IP is reduced by a significant part of expenditures on the R&D activities as well as on the creation, acquisition and development of this IP. The appropriate factor, named «nexus», is applied to calculate the tax base.

The tax relief is applicable at the end of the calendar year. This means that during the year the income tax advance payments are due according to the regular rate. Consequently in many instances the taxpayer will recover a part of the tax already paid during the previous calendar year.

It is advisable that the taxpayer applies for the individual tax ruling to the competent authority in order to receive a binding confirmation that its particular IP is eligible for the tax reduction.

It is also crucial that the taxpayer keeps the detailed accounting records of all R&D activities as well as the income and the expenses related to each R&D project (including employment costs). The records should reflect the link of incurred R&D costs with the income from intellectual property rights.

Obligations related to the application of the tax relief

In particular such a taxpayer is obliged to keep records which allow for monitoring and tracking the effects of research and development works. If, based on the accounting records kept by a taxpayer, it is not possible to determine the income (loss) from qualified intellectual property rights, the taxpayer will be obliged to pay the tax based on general rules.

The tax relief may be applied throughout the duration of the legal protection of eligible intellectual property rights.In case if a given IP is subject to notification or registration procedure (the expectative of obtaining a qualified intellectual property right), a taxpayer may benefit from tax relief from the moment of filing or submitting an application for registration. In case of withdrawal of the application, refusal of registration or rejection of the application , the amount of relief will have to be returned.

The above tax relief combined with a governmental programme of grant aid for R&D projects make Polish research, development and innovation environment more and more beneficial for investors.

Startups and Trademarks – Get it right from the Start

As a lawyer, I have been privileged to work closely with entrepreneurs of all backgrounds and ages (not just young people, a common stereotype on this field) and startups, providing legal advice on a wide range of areas.

Helping them build their businesses, I have identified a few recurrent mistakes, most of them arising mainly from the lack of experience on dealing with legal issues, and some others arising from the lack of understanding on the value added by legal advice, especially when we are referring to Intellectual Property (IP).

Both of them are understandable, we all know that startups (specially on an early stage of development) deal with the lack of financial resources and that the founders are pretty much focused on what they do best, which is to develop their own business model and structure, a new and innovative business.

Nevertheless it is important to stress that during this creation process a few important mistakes may happen, namely on IP rights, that can impact the future success of the business.

First, do not start from the end

When developing a figurative sign, a word trademark, an innovative technology that could be patentable or a software (source code), the first recommended step is to look into how to protect those creations, before showing it to third parties, namely investors or VC’s. This mistake is specially made on trademarks, as many times the entrepreneurs have already invested on the development of a logo and/or a trademark, they use it on their email signature, on their business presentations, but they have never registered the trademark as an IP right.

A non registered trademark is a common mistake and opens the door to others to copy it and to acquire (legally) rights over such distinctive sign. On the other hand, the lack of prior searches on preexisting IP rights may lead to trademark infringement, meaning that your amazing trademark is in fact infringing a preexisting trademark that you were not aware of.

Second, know what you are protecting

Basic mistake arises from those who did registered the trademark, but in a wrong or insufficient way: it is very common to see startups applying for a word trademark having a figurative element, when instead a trademark must be protected “as a whole” with their both signs (word and figurative element) in order to maximize the range of legal protection of your IP right.

Third, avoid the “classification nightmare”

The full comprehension and knowledge of the goods and services for which you apply for a trademark is decisive. It is strongly advisable for startup to have (at least) a medium term view of the business and request, on the trademark application, the full range of goods and services that they could sell or provide in the future and not only a short term view. Why? Because once the trademark application is granted it cannot be amended or added with additional goods and services. Only by requesting a new trademark application with all the costs involved in such operation.

The correct classification is crucial and decisive for a correct protection of your IP asset, especially on high technological startups where most of the time the high added value of the business arises from their IP.

On a brief, do not neglect IP, before is too late.

The author of this post is Josè Varanda

Écrire à Chiara

MetaBirkins NFT found to infringe Hermes trademark

22 mars 2023

-

ÉTATS-UNIS

- Propriété intellectuelle

‘’Made in Italy” is synonymous of high productive and aesthetic quality and represents an added value, in the international market, for different kind of products, from foodstuffs to clothing, automotive and furniture. In recent years, in Italy, a number of initiatives have been taken at the regulatory level to ensure its promotion, valorization and protection.

In 2024 came into force law no. 206/2023, referred to as the ‘New Made in Italy Law’, followed on 3 July 2024 by the related implementing Decree, by which the Ministry of Enterprise and Made in Italy (hereinafter the ‘Ministry’) introduced relevant provisions including the ones related to an official mark attesting the Italian origin of goods, the fight against counterfeiting (in particular in criminal law), and the promotion of the use of blockchain technology to protect production chains.

Among the new measures, there are specific rules for the protection of trademarks – with at least 50 years of registration or use in Italy – of particular national interest and value (hereinafter “Trademark/s”). The aim of such provisions is to safeguard the heritage represented by Italian trademarks with a long-standing presence on the market, preventing their extinction and guaranteeing their use by companies linked to the Italian territory.

Measures to guarantee the continuity

In order to protect the Trademarks, two distinct possibilities are envisaged

- Notification by companies

The first consists of the takeover by the Ministry of the ownership of Trademarks of companies that will cease their activities. In this regard, the Decree provides that a company owner or licensee of a trademark registered for at least 50 years, or for which it is possible to prove continuous use for at least 50 years, intending to cease its activity definitively, must notify the Ministry in advance of the plan to cease its activity, indicating, in particular, the economic, financial or technical reasons that impose the cessation. Upon receipt of this notification, the Ministry is entitled to take over ownership of the trademark without charge if the trademark has not been assigned for consideration by the owner or licensee company.

This procedure, in particular, is newly implemented, being applicable as of 2 December 2024.

- Revocation for non-use

The second possibility concerns Trademarks suspected of not being used for at least 5 years. In such case, the Ministry may file before the Italian Patent and Trademark Office an application for revocation for non-use and, if the application is granted, proceed with registering the Trademark in its name.

Trademarks of national interest owned by the Ministry will be announced on its Web site https://www.mimit.gov.it/it/impresa/competitivita-e-nuove-imprese/proprieta-industriale/marchi-di-interesse-storico/elenco-marchi.

As of 27 January 2025, one month after the applicability of the procedures at issue in the list are the following:

- INNOCENTI – Application number 302023000141171

- AUTOBIANCHI – Application number 302023000141189

Free licences for Italian or foreign companies wishing to invest in Italy

The Ministry is authorized to use the Trademarks, licensing them exclusively in favor of companies, including foreign ones, that intend to invest in Italy or transfer production activities located abroad to Italy.

In particular, Italian and foreign companies planning to produce in Italy may apply for a licence to use the above-mentioned Trademarks. The application shall contain specific details regarding the planned investment project, with a focus on the employment impact of the same.

Should the Ministry accept the application, the company will be granted a 10-year free licence, renewable on condition that the company maintains production activities within the national borders.

It is to be noted that, in the event that the company interrupts its activities or relocates its plants outside the Italian territory, the licence contract may be terminated immediately.

What’s next?

The recent regulatory measures are aimed, on the one hand, at keeping alive traditional brands that have been used in Italy for many years and, on the other hand, at allowing Italian and foreign companies to benefit from the incentive of free licences, if they decide to produce in Italy.

It will be interesting to monitor the business developments of these provisions in the coming months, in which the list of Trademarks owned by the Ministry will become longer.

Summary

Artist Mason Rothschild created a collection of digital images named “MetaBirkins”, each of which depicted a unique image of a blurry faux-fur covered the iconic Hermès bags, and sold them via NFT without any (license) agreement with the French Maison. HERMES brought its trademark action against Rothschild on January 14, 2022.

A Manhattan federal jury of nine persons returned after the trial a verdict stating that Mason Rothschild’s sale of the NFT violated the HERMES’ rights and committed trademark infringement, trademark dilution, and cybersquatting (through the use of the domain name “www.metabirkins.com”) because the US First Amendment protection could not apply in this case and awarded HERMES the following damages: 110.000 US$ as net profit earned by Mason Rothschild and 23.000 US$ because of cybersquatting.

The sale of approx. 100 METABIRKIN NFTs occurred after a broad marketing campaign done by Mason Rothschild on social media.

Rothschild’s defense was that digital images linked to NFT “constitute a form of artistic expression” i.e. a work of art protected under the First Amendment and similar to Andy Wahrhol’s paintings of Campbell’s soup cans. The aim of the defense was to have the “Rogers” legal test (so-called after the case Rogers vs Grimaldi) applied, according to which artists are entitled to use trademarks without permission as long as the work has an artistic value and is not misleading the consumers.

NFTs are digital record (a sort of “digital deed”) of ownership typically recorded in a publicly accessible ledger known as blockchain. Rothschild also commissioned computer engineers to operationalize a “smart contract” for each of the NFTs. A smart contract refers to a computer code that is also stored in the blockchain and that determines the name of each of the NFTs, constrains how they can be sold and transferred, and controls which digital files are associated with each of the NFTs.

The smart contract and the NFT can be owned by two unrelated persons or entities, like in the case here, where Rothschild maintained the ownership of the smart contract but sold the NFT.

“Individuals do not purchase NFTs to own a “digital deed” divorced to any other asset: they buy them precisely so that they can exclusively own the content associated with the NFT” (in this case the digital images of the MetaBirkin”), we can read in the Opinion and Order. The relevant consumers did not distinguish the NFTs offered by Rothschild from the underlying MetaBirkin image associated to the NFT.

The question was whether or not there was a genuine artistic expression or rather an unlawful intent to cash in on an exclusive valuable brand name like HERMES.

Mason Rothschild’s appeal to artistic freedom was not considered grounded since it came out that Rothschild was pursuing a commercial rather than an artistic end, further linking himself to other famous brands: Rothschild remarked that “MetaBirkins NFTs might be the next blue chip”. Insisting that he “was sitting on a gold mine” and referring to himself as “marketing king”, Rothschild “also discussed with his associates further potential future digital projects centered on luxury projects such watch NFTs called “MetaPateks” and linked to the famous Swiss luxury watches Patek Philippe.

TAKE AWAY: This is the first US decision on NFT and IP protection for trademarks.

The debate (i) between the protection of the artistic work and the protection of the trademark or other industrial property rights or (ii) between traditional artistic work and subsequent digital reinterpretation by a third party other than the original author, will lead to other decisions (in Italy, we recall the injunction order issued on 20-7-2022 by the Court of Rome in favour of the Juventus football team against the company Blockeras, producer of NFT associated with collectible digital figurines depicting the footballer Bobo Vieri, without Juventus’ licence or authorisation). This seems to be a similar phenomenon to that which gave rise some 15 years ago to disputes between trademark owners and owners of domain names incorporating those trademarks. For the time being, trademark and IP owners seem to have the upper hand, especially in disputes that seem more commercial than artistic.

For an assessment of the importance and use of NFT and blockchain in association also with IP rights, you can read more here.

In this internet age, the limitless possibilities of reaching customers across the globe to sell goods and services comes the challenge of protecting one’s Intellectual Property Right (IPR). Talking specifically of trademarks, like most other forms of IPR, the registration of a trademark is territorial in nature. One would need a separate trademark filing in India if one intends to protect the trademark in India.

But what type of trademarks are allowed registration in India and what is the procedure and what are the conditions?

The Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (the Registry) is the government body responsible for the administration of trademarks in India. When seeking trademark registration, you will need an address for service in India and a local agent or attorney. The application can be filed online or by paper at the Registry. Based on the originality and uniqueness of the trademark, and subject to opposition or infringement claims by third parties, the registration takes around 18-24 months or even more.

Criteria for adopting and filing a trademark in India

To be granted registration, the trademark should be:

- non-generic

- non-descriptive

- not-identical

- non–deceptive

Trademark Search

It is not mandatory to carry out a trademark search before filing an application. However, the search is recommended so as to unearth conflicting trademarks on file.

How to make the application?

One can consider making a trademark application in the following ways:

- a fresh trademark application through a local agent or attorney;

- application under the Paris Convention: India being a signatory to the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, a convention application can be filed by claiming priority of a previously filed international application. For claiming such priority, the applicant must file a certified copy of the priority document, i.e., the earlier filed international application that forms the basis of claim for priority in India;

- application through the Madrid Protocol: India acceded to the Madrid Protocol in 2013 and it is possible to designate India in an international application.

Objection by the Office – Grounds of Refusal

Within 2-4 months from the date of filing of the trademark application (4-6 months in the case of Madrid Protocol applications), the Registry conducts an examination and sometimes issues an office action/examination report raising objections. The applicant must respond to the Registry within one month. If the applicant fails to respond, the trademark application will be deemed abandoned.

A trademark registration in India can be refused by the Registry for absolute grounds such as (i) the trademark being devoid of any distinctive character (ii) trademark consists of marks that designate the kind, quality, quantity values, geographic origins or time or production of the goods or services (iii) the trademark causes confusion or deceives public. A relative ground for refusal is generally when a trademark is similar or deceptively similar to an earlier trademark.

Objection Hearing

When the Registry is not satisfied with the response, a hearing is scheduled within 8-12 months. During the hearing, the Registry either accepts or rejects the registration.

Publication in TM journal

After acceptance for registration, the trademark will be published in the Trade Marks Journal.

Third Party Opposition

Any person can oppose the trademark within four months of the date of publication in the journal. If there is no opposition within 4-months, the mark would be granted protection by the Registry. An opposition would lead to prosecution proceedings that take around 12-18 months for completion.

Validity of Trademark Registration

The registration dates back to the date of the application and is renewable every 10 years.

“Use of Mark” an important condition for trademark registration

- “First to Use” Rule over “First-to-File” Rule: An application in India can be filed on an “intent to use” basis or by claiming “prior use” of the trademark in India. Unlike other jurisdictions, India follows “first to use” rule over the “first-to-file” rule. This means that the first person who can prove significant use of a trade mark in India will generally have superior rights over a person who files a trade mark application prior but with a later user date or acquires registration prior but with a later user date.

- Spill-over Reputation considered as Use: Given the territorial protection granted for trademarks, the Indian Trademark Law protects the spill-over reputation of overseas trademark even where the trademark has not been used and/or registered in India. This is possible because knowledge of the trademark in India and the reputation acquired through advertisements on television, Internet and publications can be considered as valid proof of use.

Descriptive Marks to acquire distinctiveness to be eligible for registration

Unlike in the US, Indian trademark law does not generally permit registration of a descriptive trademark. A descriptive trademark is a word that identifies the characteristics of the product or service to which the trademark pertains. It is similar to an adjective. An example of descriptive marks is KOLD AND KREAMY for ice cream and CHOCO TREAT in respect of chocolates. However, several courts in India have interpreted that descriptive trademark can be afforded registration if due to its prolonged use in trade it has lost its primary descriptive meaning and has become distinctive in relation to the goods it deals with. Descriptive marks always have to be supported with evidence (preferably from before the date of application for registration) to show that the trademark has acquired a distinctive character as a result of the use made of it or that it was a well-known trademark.

Acquired distinctiveness a criterion for trademark protection

Even if a trademark lacks inherent distinctiveness, it can still be registered if it has acquired distinctiveness through continuous and extensive use. All one has to prove is that before the date of application for registration:

- the trademark has acquired a distinctive character as a result of use;

- established a strong reputation and goodwill in the market; and

- the consumers relate only to the trademark for the respective product or services due to its continuous use.

How can one stop someone from misusing or copying the trademark in India?

An action of passing off or infringement can be taken against someone copying or misusing a trademark.

For unregistered trademarks, a common law action of passing off can be initiated. The passing off of trademarks is a tort actionable under common law and is mainly used to protect the goodwill attached to unregistered trademarks. The owner of the unregistered trademark has to establish its trademark rights by substantiating the trademark’s prior use in India or trans-border reputation in India and prove that the two marks are either identical or similar and there is likelihood of confusion.

For Registered trademarks, a statutory action of infringement can be initiated. The registered proprietor only needs to prove the similarity between the marks and the likelihood of confusion is presumed.

In both the cases, a court may grant relief of injunction and /or monetary compensation for damages for loss of business and /or confiscation or destruction of infringing labels etc. Although registration of trademark is prima facie evidence of validity, registration cannot upstage a prior consistent user of trademark for the rule is ‘priority in adoption prevails over priority in registration’.

Appeals

Any decision of the Registrar of Trademarks can be appealed before the high courts within three months of the Registrar’s order.

It’s thus preferable to have a strategy for protecting trademarks before entering the Indian market. This includes advertising in publications and online media that have circulation and accessibility in India, collating all relevant records evidencing the first use of the mark in India, taking offensive action against the infringing local entity, or considering negotiations depending upon the strength of the foreign mark and the transborder reputation it carries.

Résumé

Suivons l’histoire de Nike, tirée de la biographie de son fondateur Phil Knight, pour en tirer quelques leçons sur les contrats de distribution internationaux: comment négocier le contrat, établir la durée de l’accord, définir l’exclusivité et les objectifs commerciaux, et déterminer la manière adéquate de résoudre les litiges.

Ce dont je parle dans cet article

- Le conflit entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger et la naissance de Nike

- Comment négocier un accord de distribution international

- L’exclusivité contractuelle dans un accord de distribution commerciale

- Clauses de chiffre d’affaires minimum dans les contrats de distribution

- Durée du contrat et préavis de résiliation

- La propriété des marques dans les contrats de distribution commerciale

- L’importance de la médiation dans les contrats de distribution commerciale internationale

- Clauses de règlement des litiges dans les contrats internationaux

- Comment nous pouvons vous aider

Le différend entre Blue Ribbon et Onitsuka Tiger et la naissance de Nike