-

China

China – Trade mark registration

2 February 2020

- Trademark and Patents

Quick Summary – Why is it important to register one’s trademark in China? To acquire the exclusive right to use the trademark in the Chinese market and prevent any third party from doing so, thus blocking access to the market for the foreign company’s products or services. This post describes how to register a trademark in China and why it is important to register it even if the foreign company is not yet present in the local market. We will also address the matter of a trademark in Chinese characters, illustrating in which cases it might be useful to register a transliteration of the international trademark.

Foreign Companies are often unpleasantly surprised by the fact that their trademark has already been registered in China by a local party: in such cases it is very difficult to have the trademark registration revoked and they may find themselves unable to sell their own products or services in China.

Why you should register your trademark in China

The Chinese trademark registration system is governed by the first-to-file principle, which provides for a presumption that the subject who first registers a trademark shall be considered its lawful owner (unlike other countries such as the USA and Canada, which follow the first-to-use principle, where the key is represented by the first use of the trademark).

The first-to-file principle has also been implemented by others (Italy and the European Union, for example), but its application in China is among the most stringent, as it does not entitle a previous user to continue to use a trademark once it has been registered by another subject.

Therefore, when a third party registers your distinctive mark in China first, you will no longer have the option to keep using it on Chinese territory, unless you manage to have the registration of the trademark cancelled.

In China, however, it is quite complex to get a trademark revoked, which is possible solely under one of the following circumstances.

The first one consists in proving that the third party’s registration of the trademark has been achieved by fraudulent or unlawful means. In order to do so, it is necessary to prove that the trademark registrant was aware of its previous use and has acted with the intention of obtaining an unlawful advantage, hence the registration was achieved in bad faith.

The second one involves proof that the registered trade mark is identical, similar or a translation of a well-known distinctive mark already used by another subject in China and that the new registration is likely to mislead the public. As an example, a Chinese subject registers the translation of an internationally known trademark, which had been registered in China in Latin characters only.

This second path is tricky too, because it requires the trademark to have a status of international notoriety, which under Chinese jurisprudence recurs when a large number of local consumers know and recognize the trademark.

A third case occurs when the Trademark has been registered by a third party in China, but hasn’t been used for three consecutive years: if so, the law provides that anyone who is interested may apply for the cancellation of the trademark, specifying whether he wants to cancel the entire registration or only in relation to certain classes / subclasses.

Even this third way is rather complex, especially with reference to the cancellation of the entire registration: for the Chinese trademark owner, in fact, it is sufficient to prove even a slightest use (for example on a website or a wechat account) to have the registration saved.

For these reasons, it is crucial to file the application for registration in China before a third party does so, in order to prevent similar or even identical marks/logoes from being registered – which are often in bad faith.

The process for trademark registration in China

Two alternative ways of registering a trademark in China are feasible:

- either you can file the application for registration directly with the Chinese Trademark Office (CTMO); or

- choose an international registration by submitting the relevant application to the WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization), with a subsequent designation request for an extension to China.

In my opinion, it is advisable to pursue a trademark registration directly with the CTMO (Chinese Trademark Office). International extension by the WIPO are based on a standardized registration process, which does not take into account all the complexities characterizing the Chinese system, according to which:

- The first step shall be to conduct a check in order to ascertain whether similar and/or identical trademarks have already been registered, along with an evaluation of the legal requirements for the trademark’s validity.

- Second, the applicant must select the class(es) and sub-class(es) under which the relevant trade mark is to be registered.

This process is somewhat complex, since the CTMO, besides the designation of the class of registration within the 45 classes covered by the International Classification (“Nice Classification of Goods and Services”), requires as well an indication of the subclasses. There are several Chinese subclasses for each class, and they do not match with the International Classification.

As a consequence, by submitting your application through the WIPO, your trade mark would be registered in the correct class, but the designation of the subclasses will be made ex officio by the CTMO, without the applicant being involved. This may lead to the registration of the trademark in subclasses that do not correspond to the ones desired, entailing the risk, on the one hand, of an increase in registration costs (if the subclasses are inflated); on the other hand, it may result in a limited protection on the market (if the trademark is not registered under a certain subclass).

Another practical aspect which would make direct registration in China preferable lies in the immediate gain of a certificate in Chinese; this enables you to move quickly and effectively (with no need for additional certificates or translations) in case you need to use your trademark in China (e.g. for legal or administrative actions against counterfeit or if you need to register a trademark license agreement).

The registration procedure in China itself involves several steps and is generally concluded within a time frame of about 15/18 months: priority, however, is acquired from the date of filing, thus ensuring protection against any application for registration by a third party at a later date.

Registration lasts 10 years and is renewable.

Trade mark registration in Chinese characters

Is it really necessary to register the Trademark also in Chinese characters?

For most companies, yes. Very few people speak English in China, so international terms are often difficult to pronounce and are often replaced by a Chinese word that sounds like the foreign word, making it easier for Chinese consumers or customers to read and memorize it.

Transliteration of the international trademark into Chinese characters can be achieved in several ways.

First of all, it is possible to register a term that presents assonance with the original, as in the case of Ferrari / 法拉利 (fǎlālì, phonetic transliteration without particular meaning) or Google / 谷歌 (Gǔgē, also a phonetic transliteration).

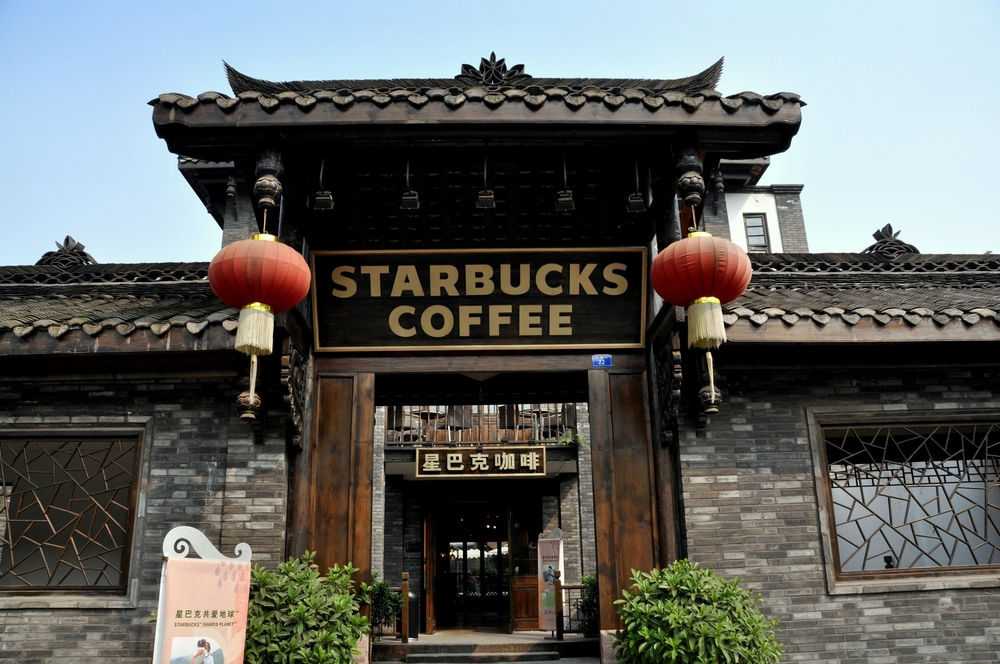

As an alternative a term equivalent to the meaning of the foreign word can be chosen, such as in the case of Apple / 苹果(Píngguǒ, which means apple) and partly in the case of Starbucks / 星巴克 (xīngbākè: the first character means “star”, while bākè is a phonetic transliteration).

The third option would be to identify a term that carries both a positive meaning related to the product and at the same time recalls the sound of the foreign brand, as in the case of Coca Cola / Kěkǒukělè (i.e. taste and be happy).

(Below the trademark Ikea / 宜家 =yíjiā, namely harmonious home)

As for the trademark in Latin characters, there is a strong risk that third parties may register the Chinese version of the trademark before the lawful owner.

This is compounded by the fact that the third party who registers a similar or confusing trademark in Chinese characters typically does so in order to exploit unfairly the fame and the commercial goodwill of the foreign trademark by addressing the same customers and sales channels.

Recently, the Jordan (owned by the group of companies belonging to the basketball champion) and New Balance, for example, struggled for some time to have their corresponding Chinese trademarks cancelled, which had been registered in bad faith by their competitors.

Registration rules for a trademark in Chinese characters are the same as those mentioned above for a trademark in Latin characters.

Since there may be risks related to possible third party registrations, it is advisable to extend the assessment of trademark registration not only to the Chinese characters that have been identified for the Mandarin version that you decided to use, but also to a number of phonetically similar trademarks, which should prevent any third party from registering trademarks that may be confused with the company’s trademark.

Furthermore, it is also advisable to register a trademark in Chinese characters, even if the business strategy does not involve the use of a trademark in Chinese characters. In such cases, the registration of terms that correspond to the phonetic transliteration of the international trademark serves a protective purpose, namely to prevent registration (and use) by third parties.

The latter has been done, for example, by important brands such as Armani and Prada, which have registered trademarks in Chinese characters (respectively 阿玛尼 / āmǎní and 普拉達 = pǔlādá) although they do not currently use them in their communication.

Regarding the different transliteration options, it is advisable to be supported by local consultants in the evaluation of the characters, to avoid choosing terms with unhappy, unsuitable or even inauspicious meanings (as in the case of one of my clients who registered an Italian trademark many years ago using the final character 死, which sounds like the word “dead” in Chinese).