-

Brasile

When Life Gives You Tariffs… Make New Allies: Brazil, Europe and a New Trade Chapter

3 Aprile 2025

- Distribuzione

- Fisco e tasse

The Brazilian market has not been immune to the protectionist wave of “America First.” If such measures persist over time, they could have a lasting impact on the local economy. Still, a sour lemon can often become a sweet caipirinha in the resilient and optimistic spirit that characterizes both Brazilian society and its entrepreneurs.

As is often the case in the chessboard of global economic geopolitics, a move from one player creates room for another countermove. Brazil reacted with reciprocal trade measures, signaling clearly that it would not accept a position of commercial vulnerability.

This firmer stance — almost unthinkable in earlier years — strengthened Brazil’s image in Europe as a country ready to reposition itself with greater autonomy and pragmatism, opening new doors to international markets. In a world where global value chains are being restructured and reliable trade partners are in high demand, Brazil is increasingly seen not just as a supplier of raw materials, but as a strategic partner in critical industries.

The rapprochement with Europe has been further energized by progress in the Mercosur–European Union Agreement, whose negotiations spanned decades and now seem to be gaining momentum. While the United States embraces a more isolationist commercial posture, Europe is actively diversifying its trade relations — and Brazil, by demonstrating a commitment to clear rules, economic stability, and legal certainty, emerges as a natural candidate to fill that gap.

The Direct Impact of U.S. Tariffs

The trade measures introduced under President Trump primarily affected Brazilian producers of semi-finished steel and primary aluminum, with the removal of long-standing exemptions and quotas. In 2024, Brazil exported US$ 2.2 billion in semi-finished steel to the United States, representing nearly 60% of U.S. imports in that category. In the same year, Brazilian aluminum exports to the U.S. reached US$ 796 million, accounting for 14% of the sector’s total. Losses in exports for 2025 are estimated at around US$ 1.5 billion.

Brazil’s Response and a New Phase

In April 2025, the Brazilian Congress passed a new legal framework for trade retaliation, empowering the Executive Branch to adopt countermeasures in a faster and more technically structured way. The new legislation allows, for example, the automatic imposition of retaliatory tariffs on goods from countries that adopt unilateral measures incompatible with WTO norms; the suspension of tax or customs benefits previously granted under bilateral agreements; the creation of a list of priority sectors for trade defense and diversification of export markets.

Beyond the retaliation itself, the move marked a significant shift in posture: Brazil began positioning itself as an active player in global trade governance, aligning with mid-sized economies that advocate for predictable, balanced, and rules-based trade relations.

An Opportunity for Brazil–Europe Relations

This new stage sets Brazil as a reliable supplier to European industry — not only of raw materials but also of higher-value-added goods, particularly in processed foods, bioenergy, critical minerals, pharmaceuticals, and infrastructure.

Moreover, as US–China tensions drive European companies to seek nearshoring or “friend-shoring” strategies with more predictable partners, Brazil, with its clean energy matrix, large domestic market, and relatively stable institutions, emerges as a strong alternative.

Legal Implications and Strategic Recommendations

This changing landscape brings new opportunities for companies and legal advisors involved in Brazil–Europe investment and trade relations. Particular attention should be paid to:

- Monitoring rules of origin in the Mercosur–EU agreement, especially in sectors requiring supply chain restructuring;

- Reviewing contractual and tax structures for import/export operations, including clauses addressing tariff instability or non-tariff barriers (e.g., environmental or sanitary standards), and clearly defining force majeure events;

- Reassessing distribution and agency agreements in light of the new commercial environment;

- Exploring joint ventures and technology transfer arrangements with Brazilian partners, particularly in bioeconomy, green hydrogen, and mineral processing.

From lemon to caipirinha

The world is becoming more fragmented and competitive, but also more open to realignment. What began as a protectionist blow from the United States has revealed new opportunities for transatlantic cooperation. For Brazil, Europe is no longer just a client: it is poised to become a long-term strategic partner. It is now up to lawyers and businesses on both sides of the Atlantic to turn this opportunity into lasting, mutually beneficial relationships.

Il 2 Aprile 2025 entreranno in vigore le tariffe USA verso i prodotti provenienti dalla UE.

Visto quanto accaduto con le tariffe imposte a Canada e Messico, con una rincorsa di annunci di entrata in vigore e sospensioni e nuovi annunci, è impossibile fare previsioni anche di breve termine.

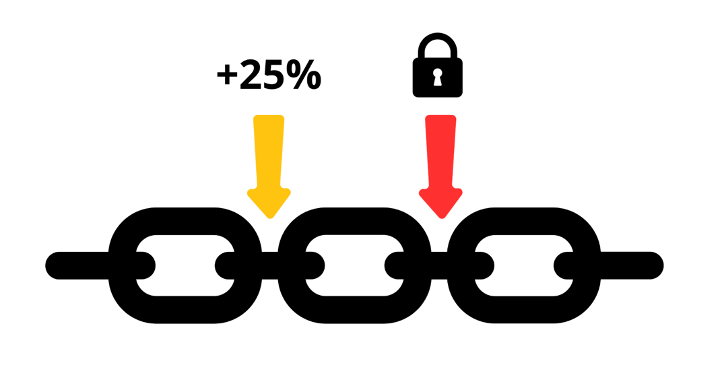

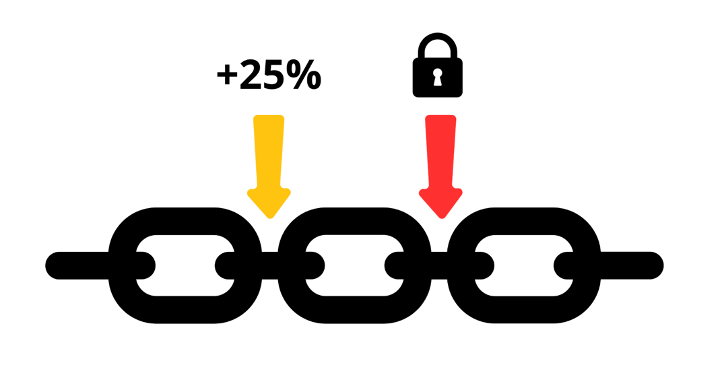

Occorre prepararsi alla possibilità di imposizione del dazio, che è un evento prevedibile e previsto, che, come tale, va disciplinato nel contratto. Non farlo rischia di costare molto caro, perchè non ci sono argomenti validi per sottrarsi all’adempimento dei contratti già conclusi invocando una situazione di Forza Maggiore (che non sussiste, perché la prestazione non è divenuta oggettivamente impossibile) o di eccessiva onerosità sopravvenuta (in inglese Hardship: anche in caso di aumenti ben oltre il 25%, la giurisprudenza esclude che si possa invocare).

La cautela che si può adottare è quella di negoziare una clausola di aggiornamento dei prezzi, espressamente riferita al caso del dazio, che rispetti i requisiti richiesti dalla giurisprudenza americana per questo tipo di clausole.

Una prima clausola utile può essere la c.d. Escalator o Price Adjustment Clause, con la quale si prevede il diritto di rinegoziare il prezzo nel caso di imposizione di un dazio superiore ad una certa soglia, ad esempio:

PRICE ADJUSTMENT CLAUSE

Triggering Event

A “Triggering Event” shall be deemed to occur if:

- There is an increase in customs duties or the introduction of new trade barriers not previously contemplated, resulting in an increase in the total price of the goods or services by X% or more.

- Such an increase affects either (i) the Buyer directly or (ii) the Seller due to tariffs imposed on its upstream suppliers, materially impacting the cost of performance.

Trigger Mechanism

In the event of a Triggering Event:

- The affected Party shall notify the other Party in writing within thirty (30) days of the effective date of the customs duty change or the introduction of the new trade barrier.

- The notification must include supporting documentation demonstrating the financial impact of the Triggering Event.

Renegotiation Process

Upon receipt of a valid notification, the Parties shall engage in good-faith negotiations for sixty (60) days to agree on an adjusted price that reflects the increased costs.

Failure to Reach an Agreement

If the Parties fail to reach an agreement on the price adjustment within the prescribed sixty (60) days:

Option 1 – Contract Termination: Either Party shall have the right to terminate the contract by providing written notice to the other Party, without liability for damages, except for obligations already accrued up to the termination date.

Option 2 – Third-Party Arbitrator: The Parties shall appoint an independent third-party arbitrator with expertise in international trade and pricing. The arbitrator shall determine a fair market price, which shall be binding on both Parties. The cost of the arbitrator shall be borne equally by both Parties unless otherwise agreed.

***

Un altro possibile strumento in alternativa alla clausola appena vista è c.d. Cost Sharing clause, dove si menziona già l’accordo sulla suddivisione dei costi addizionali conseguenti all’imposizione del dazio, ad esempio:

COST SHARING CLAUSE

Triggering Event

A “Triggering Event” shall be deemed to occur if there is an increase in customs duties or the introduction of new trade barriers not previously contemplated, resulting in an increase in the total price of the goods by [X]% or more. Such an increase will be borne by the Buyer by up to [X]%, while higher increases will be shared equally between the seller and buyer.

***

E’ opportuno che tali clausole vengano calate negli accordi caso per caso, per riflettere al meglio gli scenari che si prevede possano influenzare il prezzo dei prodotti, ossia

- imposizione di dazio in ingresso USA

- imposizione di dazio in ingresso UE

ma anche effetti indiretti, come quello in cui sia il venditore ad invocare la rinegoziazione del prezzo, ad esempio perché il prezzo del prodotto è aumentato a causa del dazio pagato da un suo fornitore a monte della supply chain, nel quale caso è importante identificare quali siano i prodotti rilevanti e documentare gli aumenti derivanti dall’imposizione delle tariffe.

I dazi non li pagano i governi stranieri (come ripetuto più volte da Donald Trump in campagna elettorale) ma le imprese importatrici del paese che emette la tassa sul valore del prodotto importato, ossia, nel caso del recente round di dazi dell’amministrazione Trump, le imprese statunitensi. Allo stesso modo, saranno le imprese canadesi, messicane, cinesi e – probabilmente – europee, che pagheranno i dazi per l’import dei prodotti di provenienza USA, applicati dai rispettivi paesi come misura di ritorsione commerciale nei confronti dei dazi statunitensi.

In questo contesto, si aprono diversi scenari, tutti problematici:

- Per le imprese USA, che versano la tassa di importazione

- Per le imprese straniere che esportano verso gli USA i prodotti tassati, che per effetto dell’aumento dei prezzi vedranno calare i volumi di export

- Per le imprese straniere che importano prodotti dagli USA, perché a loro volta pagheranno i dazi imposti dai loro paesi come ritorsione a quelli americani

- Per i clienti intermedi o finali nei mercati interessati dai dazi, che pagheranno un prezzo più alto sui prodotti importati

L’imposizione del dazio costituisce causa di forza maggiore?

Una prima obiezione frequente della parte colpita dal dazio (può essere il compratore-importatore, oppure chi rivende il prodotto dopo avere pagato il dazio), in questi casi, è quella di invocare la forza maggiore per sottrarsi all’adempimento del contratto, che per effetto del dazio è divenuto troppo oneroso.

L’applicazione del dazio, però, non rientra tra le cause di forza maggiore, poiché non siamo di fronte ad un evento imprevedibile, che comporti l’impossibilità oggettiva di adempiere al contratto. Il compratore / importatore, infatti, può sempre dare adempimento al contratto, con la sola problematica dell’aumento del prezzo.

L’imposizione del dazio costituisce causa di eccessiva onerosità sopravvenuta (hardship)?

Se ricorre una situazione di eccessiva onerosità sopravvenuta dopo la conclusione del contratto (in inglese, harship) la parte colpita ha diritto di chiedere una revisione del prezzo, oppure di terminare il contratto.

Occorre una valutazione caso per caso, che porta a ritenere ricorrente una situazione di hardship se ricorra una situazione straordinaria ed imprevedibile (nel caso dei dazi USA, annunciati da mesi, difficile sostenerlo) e il prezzo, per effetto dell’applicazione del dazio, sia manifestamente eccessivo.

Si tratta di situazioni eccezionali, di rara applicazione, che vanno approfondite sulla base della legge applicabile al contratto. In linea generale le fluttuazioni di prezzo sui mercati internazionali rientrano nel rischio d’impresa e non costituiscono motivo sufficiente per rinegoziare gli accordi conclusi, che restano vincolanti, salvo che le parti non abbiano previsto una clausola di hardship nell’accordo (ne parliamo in seguito).

L’applicazione del dazio comporta un diritto a rinegoziare i prezzi?

I contratti già conclusi, ad esempio gli ordini già accettati e i programmi di fornitura con prezzi concordati per un certo periodo, restando vincolanti e devono essere eseguiti secondo gli accordi originari.

In assenza di clausole specifiche nel contratto, la parte colpita dal dazio è dunque obbligata a rispettare il prezzo precedentemente pattuito e dare adempimento all’accordo.

Le parti sono libere di rinegoziare i futuri contratti, ad esempio

- il venditore può concedere uno sconto per diminuire l’impatto del dazio che colpisce il compratore-importatore, oppure

- il compratore può acconsentire ad un aumento del prezzo per compensare un dazio che il venditore abbia pagato per importare un componente o una semilavorato nel suo paese, per poi esportare il prodotto finito

ma ciò non riguarda la validità degli impegni già contrattualizzati, che restano vincolanti.

La situazione è particolarmente delicata per le imprese che si trovano nel mezzo della catena di fornitura, ad esempio chi importa materie prime o componenti dall’estero (potenzialmente oggetto di dazi, o di doppi dazi in caso di ripetuta importazione ed esportazione) e rivende i prodotti semilavorati o finiti, con ordinativi confermati a lungo termine, o accordi di fornitura a prezzo fisso per un certo periodo. In caso di contratti già conclusi, chi ha importato un prodotto accollandosi il dazio non ha diritto di trasferire il costo sul successivo anello della supply chain, a meno che ciò non fosse espressamente previsto nel contratto con il cliente.

Come tutelarsi nel caso di imposizione di futuri dazi che colpiscano fornitori o clienti stranieri?

E’ consigliabile prevedere espressamente il diritto di rinegoziare i prezzi, se necessario aggiungendo con un addendum all’accordo originario. Il risultato si ottiene, ad esempio, con una clausola che preveda che nel caso di eventi futuri, compresi eventuali dazi, che comportino un aumento del costo complessivo del prodotto sopra una certa soglia (ad esempio il 10%), la parte colpita dal dazio abbia il diritto di avviare una rinegoziazione del prezzo e, in caso di manco accordo, possa recedere dal contratto.

Un esempio di clausola può essere il seguente:

Import Duties Adjustment

“If any new import duties, tariffs, or similar governmental charges are imposed after the conclusion of this Contract, and such measures increase a Party’s costs exceeding X% of the agreed price of the Products, the affected Party shall have the right to request an immediate renegotiation of the price. The Parties shall engage in good faith negotiations to reach a fair adjustment of the contractual price to reflect the increased costs.

If the Parties fail to reach an agreement within [X] days from the affected Party’s request for renegotiation, the latter shall have the right to terminate this Contract with [Y] days’ written notice to other Party, without liability for damages, except for the fulfillment of obligations already accrued.”

“Questo accordo non è solo un’opportunità economica. È una necessità politica“. Nell’attuale contesto geopolitico, caratterizzato da un crescente protezionismo e da importanti conflitti regionali, la dichiarazione di Ursula von der Leyen la dice lunga.

Anche se c’è ancora molta strada da fare prima che l’accordo venga approvato internamente a ciascun blocco ed entri in vigore, la pietra miliare è molto significativa. Ci sono voluti 25 anni dall’inizio dei negoziati tra il Mercosur e l’Unione Europea per raggiungere un testo di consenso. L’impatto sarà notevole. Insieme, i blocchi rappresentano un PIL di oltre 22 mila miliardi di dollari e ospitano oltre 700 milioni di persone.

Vediamo le informazioni più importanti sul contenuto dell’accordo e sul suo stato di avanzamento.

Che cos’è l’accordo EU-Mercosur?

L’accordo è stato firmato come trattato commerciale, con l’obiettivo principale di ridurre le tariffe di importazione e di esportazione, eliminare le barriere burocratiche e facilitare il commercio tra i Paesi del Mercosur e i membri dell’Unione Europea. Inoltre, il patto prevede impegni in aree quali la sostenibilità, i diritti del lavoro, la cooperazione tecnologica e la protezione dell’ambiente.

Il Mercosur (Mercato Comune del Sud) è un blocco economico creato nel 1991 da Brasile, Argentina, Paraguay e Uruguay. Attualmente, Bolivia e Cile partecipano come membri associati, accedendo ad alcuni accordi commerciali, ma non sono pienamente integrati nel mercato comune. D’altra parte, l’Unione Europea, con i suoi 27 membri (20 dei quali hanno adottato la moneta comune), è un’unione più ampia con una maggiore integrazione economica e sociale rispetto al Mercosur.

Cosa prevede l’accordo UE-Mercosur?

Scambio di beni:

- Riduzione o eliminazione delle tariffe sui prodotti scambiati tra i blocchi, come carne, cereali, frutta, automobili, vini e prodotti lattiero-caseari (la riduzione prevista riguarderà oltre il 90% delle merci scambiate tra i blocchi).

- Accesso facilitato ai prodotti europei ad alta tecnologia e industrializzati.

Commercio di servizi:

- Espande l’accesso ai servizi finanziari, alle telecomunicazioni, ai trasporti e alla consulenza per le imprese di entrambi i blocchi.

Movimento di persone:

- Fornisce agevolazioni per visti temporanei per lavoratori qualificati, come professionisti della tecnologia e ingegneri, promuovendo lo scambio di talenti.

- Incoraggia i programmi di cooperazione educativa e culturale.

Sostenibilità e ambiente:

- Include impegni per combattere la deforestazione e raggiungere gli obiettivi dell’Accordo di Parigi sul cambiamento climatico.

- Prevede sanzioni per le violazioni degli standard ambientali.

Proprietà intellettuale e normative:

- Protegge le indicazioni geografiche dei formaggi e dei vini europei e del caffè e della cachaça sudamericani.

- Armonizza gli standard normativi per ridurre la burocrazia ed evitare le barriere tecniche.

Diritti del lavoro:

- Impegno per condizioni di lavoro dignitose e rispetto degli standard dell’Organizzazione Internazionale del Lavoro (OIL).

Quali benefici aspettarsi?

- Accesso a nuovi mercati: Le aziende del Mercosur avranno un accesso più facile al mercato europeo, che conta più di 450 milioni di consumatori, mentre i prodotti europei diventeranno più competitivi in Sud America.

- Riduzione dei costi: L’eliminazione o la riduzione delle tariffe doganali potrebbe abbassare i prezzi di prodotti come vini, formaggi e automobili e favorire le esportazioni sudamericane di carne, cereali e frutta.

- Rafforzamento delle relazioni diplomatiche: L’accordo simboleggia un ponte di cooperazione tra due regioni storicamente legate da vincoli culturali ed economici.

Quali sono i prossimi passo?

La firma è solo il primo passo. Affinché l’accordo entri in vigore, deve essere ratificato da entrambi i blocchi e il processo di approvazione è ben distinto tra loro, poiché il Mercosur non ha un Consiglio o un Parlamento comuni.

Nell’Unione Europea, il processo di ratifica prevede molteplici passaggi istituzionali:

- Consiglio dell’Unione Europea: I ministri degli Stati membri discuteranno e approveranno il testo dell’accordo. Questa fase è cruciale, poiché ogni Paese è rappresentato e può sollevare specifiche preoccupazioni nazionali.

- Parlamento europeo: Dopo l’approvazione del Consiglio, il Parlamento europeo, composto da deputati eletti, vota per la ratifica dell’accordo. Il dibattito in questa fase può includere gli impatti ambientali, sociali ed economici.

- Parlamenti nazionali: Nei casi in cui l’accordo riguardi competenze condivise tra il blocco e gli Stati membri (come le normative ambientali), deve essere approvato anche dai parlamenti di ciascun Paese membro. Questo può essere impegnativo, dato che Paesi come la Francia e l’Irlanda hanno già espresso preoccupazioni specifiche sulle questioni agricole e ambientali.

Nel Mercosur, l‘approvazione dipende da ciascun Paese membro:

- Congressi nazionali: Il testo dell’accordo viene sottoposto ai parlamenti di Brasile, Argentina, Paraguay e Uruguay. Ogni congresso valuta in modo indipendente e l’approvazione dipende dalla maggioranza politica di ciascun Paese.

- Contesto politico: I Paesi del Mercosur hanno realtà politiche diverse. In Brasile, ad esempio, le questioni ambientali possono suscitare accesi dibattiti, mentre in Argentina l’impatto sulla competitività agricola può essere al centro della discussione.

- Coordinamento regionale: Anche dopo l’approvazione nazionale, è necessario garantire che tutti i membri del Mercosur ratifichino l’accordo, poiché il blocco agisce come un’unica entità negoziale.

Seguite questo blog, vi terremo aggiornato sugli sviluppi.

When selling health-related products, the question frequently arises as to which product category, and therefore which regulatory regime, they fall under. This question often arises when distinguishing between food supplements and medicinal products. But in other constellations, too, difficult questions of demarcation arise, which must be answered with a view to legally compliant marketing.

In a highly interesting case, the Administrative Court (Verwaltungsgericht) of Düsseldorf, Germany, recently had to classify a CBD-containing (Cannabidiol) mouth spray that was explicitly advertised by its manufacturer as a “cosmetic” and therefore not suitable for human consumption. The Ingredients of the product were labelled: « Cannabis sativa seed oil, cannabidiol from cannabis extract, tincture or resin, cannabis sativa leaf extract ».

The Product is additionally also labelled as follows: “Cosmetic oral care spray with hemp leaf extract. » The Instructions for use are: « Spray a maximum of 3 sprays a day into the mouth as desired. Spit out after 30 seconds and do not swallow. »

A spray of the Product contains 10 mg CBD. This results in a maximum daily dose of 30 mg CBD as specified by the company.

At the same time, however, it was pointed out that the “consumption” of a spray shot was harmless to health.

The mouth spray could therefore be consumed like a food, but was declared as a “cosmetic”. This is precisely where the court had to examine whether the prohibition order based on food law was lawful.

For the definition of cosmetic products Article 2 sentence 4 lit. e) Regulation (EC) No. 178/2002 refers to Directive 76/768/EEC. This was replaced by Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009. Cosmetic products are defined in Article 2(1)(a) as follows: “‘cosmetic product’ means any substance or mixture intended to be placed in contact with the external parts of the human body (epidermis, hair system, nails, lips and external genital organs) or with the teeth and the mucous membranes of the oral cavity with a view exclusively or mainly to cleaning them, perfuming them, changing their appearance, protecting them, keeping them in good condition or correcting body odours ”.

Here too, it is not the composition of the product that is decisive, but its intended purpose, which is to be determined on the basis of objective criteria according to general public opinion based on concrete evidence.

According to the system of Regulation (EC) No. 178/2002, Article 2 sentence 1 first defines foodstuffs in general and then excludes cosmetic products under sentence 4 lit. e). According to the definition in Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009, cosmetic products must have an exclusive or at least predominant cosmetic purpose. It can be concluded from this system that the exclusivity or predominance must be positively established. If it is not possible to determine which purpose predominates, the product is a foodstuff.

The Düsseldorf Administrative Court had to deal with this question in the aforementioned legal dispute brought by the distributor against an official prohibition order in the form of a so-called general ruling („Allgemeinverfügung“). By notice dated July 11, 2020, the competent authority issued a general ruling prohibiting the marketing of foodstuffs containing “cannabidiol (as ‘CBD isolates’ or ‘hemp extracts enriched with CBD’)” in their urban area. The company, based in this city, offered the mouth spray described above.

In a ruling dated 25.10.2024 (Courts Ref. : 26 K 2072/23), the court dismissed the company’s claim. The court’s main arguments were :

- Classification as food: the CBD spray was correctly classified as food by the authority, as it was reasonable to expect that it could be swallowed despite indications to the contrary. According to an objective perception of the market, there is a now established expectation of an average informed, attentive and reasonable consumer to the effect that CBD oils are intended as “lifestyle” products for oral ingestion, from which consumers hope for positive health effects The labelling as “cosmetic” was refuted by the objective consumer expectations and the nature of the application.

- No medicinal product status: Due to the low dosage in this case (max. 30 mg CBD per day), the product was not classified as a functional medicinal product, as there was no sufficiently proven pharmacological effect.

- Legal basis of the injunction: The prohibition of the sale of the products by the defendant was based on a general order, which was confirmed as lawful by the court.

In the ruling, the court emphasizes the objective consumer expectation and clarifies that products cannot be exempted from a different regulatory classification by the authorities or the courts solely by their labelling.

Conclusion: The decision presented underlines the considerable importance of the “correct” classification of a health product in the respective legal product category. In addition to the classic distinction between foodstuffs (food supplements) and medicinal products, comparable issues also arise with other product types. In this case in the constellation of cosmetics versus food – combined with the special legal component of the use of CBD.

Commercial agents have specific regulations with rights and obligations that are “mandatory”: those who sign an agency contract cannot derogate from them. Answering whether an influencer can be an agent is essential because, if he or she is an agent, the agent regulations will apply to him or her.

Let’s take it one step at a time. The influencer we will talk about is the person who, with their actions and comments (blogs, social media accounts, videos, events, or a bit of everything), talks to their followers about the advantages of certain products or services identified with a certain third-party brand. In exchange for this, the influencer is paid.[1]

A commercial agent is someone who promotes the contracting of others’ products or services, does so in a stable way, and gets paid in return. He or she can also conclude the contract, but this is not essential.

The law imposes certain obligations and guarantees rights to those signing an agency contract. If the influencer is considered an “agent”, he or she should also have them. And there are several of them: for example, the duration, the notice to be given to terminate the contract, the obligations of the parties… And the most relevant, the right of the agent to receive compensation at the end of the relationship for the clientele that has been generated. If an influencer is an agent, he would also have this right.

How can an influencer be assessed as an agent? For that we must analyse two things: (a) the contract (and be careful because there is a contract, even if it is not written) and (b) how the parties have behaved.

The elements that, in my opinion, are most relevant to conclude that an influencer is an agent would be the following:

a) the influencer promotes the contracting of services or the purchase of products and does so independently.

The contract will indicate what the influencer must do. It will be clearer to consider him as an agent if his comments encourage contracting: for example, if they include a link to the manufacturer’s website, if he offers a discount code, if he allows orders to be placed with him. And if he does so as an independent “professional”, and not as an employee (with a timetable, means, instructions).

It may be more difficult to consider him as an agent if he limits himself to talking about the benefits of the product or service, appearing in advertising as a brand image, and using a certain product, and speaking well of it. The important thing, in my opinion, is to examine whether the influencer’s activity is aimed at getting people to buy the product he or she is talking about, or whether what he or she is doing is more generic persuasion (appearing in advertising, lending his or her image to a product, carrying out demonstrations of its use), or even whether he or she is only seeking to promote himself or herself as a vehicle for general information (for example, influencers who make comparisons of products without trying to get people to buy one or the other). In the first case (trying to get people to buy the product) it would be easier to consider it as an “agent”, and less so in the other examples.

b) this “promotion” is done in a continuous or stable manner.

Be careful because this continuity or stability does not mean that the contract has to be of indefinite duration. Rather, it is the opposite of a sporadic relationship. A one-year contract may be sufficient, while several unconnected interventions, even if they last longer, may not be sufficient.

In this case, influencers who make occasional comments, who intervene with isolated actions, who limit themselves to making comparisons without promoting the purchase of one or the other, and even if all this leads to sales, even if their comments are frequent and even if they can have a great influence on the behavior of their followers, would be excluded as agents.

c) they receive remuneration for their activity.

An influencer who is remunerated based on sales (e.g., by promoting a discount code, a specific link, or referring to your website for orders) can more easily be considered as an agent. But also, if he or she only receives a fixed amount for their promotion. On the other hand, influencers who do not receive any remuneration from the brand (e.g. someone who talks about the benefits of a product in comparison with others, but without linking it to its promotion) would be excluded.

Conclusion

The borderline between what qualifies an influencer as an agent and what does not can be very thin, especially because contracts are often not unambiguous and sometimes their services are multiple. The most important thing is to carefully analyse the contract and the parties’ behaviour.

An influencer could be considered a commercial agent to the extent that his or her activity promotes the contracting of the product (not simply if he or she carries out informative or image work), that it is done on a stable basis (and not merely anecdotal or sporadic) and in exchange for remuneration.

To assess the specific situation, it is essential to analyse the contract (if it is written, this is easier) and the parties’ behaviour.

In short, to draw up a contract with an influencer or, if it has already been signed, but you want to conclude it, you will have to pay attention to these elements. As an influencer you may have a strong interest in being considered an agent at the end of the contract and thus be entitled to compensation, while as employer you will prefer the opposite.

FINAL NOTE. In Spain and at the date of this comment (9 June 2024) I am not aware of any judgement dealing with this issue. My proposal is based on my experience of more than 30 years advising and litigating on agency contracts. On the other hand, and as far as I know, there is at least one judgment in Rome (Italy) dealing with the matter: Tribunale di Roma; Sezione Lavoro 4º, St. 2615 of 4 March 2024; R. G. n. 38445/2022.

La legge contro l’ultra fast-fashion è stata concepita per fronteggiare la crescente preoccupazione riguardante l’impatto ambientale, economico e sulla salute provocato dall’inondazione del mercato con tessuti e accessori di moda da parte di giganti come SHEIN, TEMU, PRIMARK e altri. Queste aziende, spesso trascurando le conseguenze delle loro pratiche, hanno contribuito significativamente all’incremento delle emissioni di gas serra attribuite all’industria tessile, che ora si stima essere responsabile per circa l’8% del totale globale.

In un contesto dove la produzione globale di abbigliamento ha visto un raddoppio in soli 14 anni e la durata di vita degli indumenti si è ridotta di un terzo, il marchio SHEIN ha registrato una crescita esponenziale del 100% tra il 2021 e il 2022, evidenziando ulteriormente la problematica del fast fashion che domina il mercato francese, nonostante in alcuni settori si stia vivendo una rinascita dell’artigianalità e del design made in France.

La risposta delle autorità francesi si è concretizzata nel disegno di legge n. 2129, volto a ridurre l’impatto ambientale dell’industria tessile, proposto da un deputato del Governo e adottato all’unanimità dall’Assemblea Nazionale il 14 marzo 2024, che nelle prossime settimane verrà esaminato dal Senato con una procedura accelerata, prima della definitiva adozione.

Questa normativa si propone di sensibilizzare i consumatori sull’importanza della sobrietà e della sostenibilità nell’industria della moda, promuovendo pratiche di riutilizzo, riparazione, e riciclaggio, e introducendo penalizzazioni per i produttori che non rispettano determinati standard ecologici.

Di seguito le misure principali.

1. Definizione legale di fast-fashion e obblighi informativi

Viene istituita una definizione legale di fast-fashion, identificato come la pratica di “messa a disposizione o distribuzione di un gran numero di riferimenti a nuovi prodotti (…) anche attraverso un fornitore di mercato online” e gli operatori di questo settore hanno l’obbligo di “visualizzare sulle loro piattaforme di vendita online messaggi che incoraggino la sobrietà, il riutilizzo, la riparazione e il riciclaggio dei prodotti e che sensibilizzino sul loro impatto ambientale. Il messaggio deve essere visualizzato in modo chiaro, leggibile e comprensibile su qualsiasi formato utilizzato, in prossimità del prezzo. Il contenuto dei messaggi è definito per decreto.”

Questa norma disciplina tutte le vendite online (anche su piattaforme) mentre non include le piattaforme per la rivendita di prodotti invenduti.

La violazione di questa disposizione comporta sanzioni amministrative fino a 3.000 € per le persone fisiche e 15.000 € per le persone giuridiche.

2. Limiti alla pubblicità (anche tramite influencer)

Il disegno di legge vieta la pubblicità dei prodotti di fast fashion, anche tramite influencer, al fine di ridurre la promozione di pratiche insostenibili nell’industria della moda, incentivando così un cambiamento nei modelli di consumo.

In caso di adozione definitiva, questa disposizione entrerà in vigore a partire dal 1o gennaio 2025.

La violazione di questa disposizione comporta sanzioni amministrative fino a 20.000 € per le persone fisiche e 100.000 € per le persone giuridiche, e fino al raddoppio in caso di recidiva.

3. Altri obblighi e sistema di disincentivi

La legge riguarda tutti i produttori (industriali, fabbricanti, grossisti, importatori), distributori e rivenditori francesi al pubblico e prevede anche altri obblighi, come: l’adesione a un’organizzazione ecologica (Refashion), il pagamento di un eco-contributo, l’etichettatura conforme e l’obbligo di esporre i risultati della valutazione dell’impatto ambientale del prodotto, che può portare ad una sanzione o all’ottenimento di un bonus.

Etichettatura e sull’eco-contributo CTA

La legge AGEC prevede attualmente una sanzione massima del 20% del prezzo di vendita del prodotto, IVA esclusa, se questo presenta caratteristiche ambientali scadenti. Considerati i prezzi a cui i prodotti fast-fashion sono venduti ai consumatori, l’impatto sui produttori è minimo (ad esempio, una maglietta da 4 euro), pertanto ora la proposta è quella di innalzare questa sanzione a un massimo del 50% del prezzo di vendita del prodotto.

Questa sanzione sarà determinata in base all’obbligo di mostrare l’analisi dell’impatto ambientale del prodotto. Le sanzioni saranno quindi fisse (e non in percentuale sul prezzo del prodotto), sotto forma di un malus progressivo fino al 2030:

- 5 euro per ogni prodotto immesso sul mercato nel 2025

- 6 euro per ogni prodotto immesso sul mercato nel 2026

- 7 euro per ogni prodotto immesso sul mercato nel 2027

- 8 euro per ogni prodotto immesso sul mercato nel 2028

- 9 euro per ogni prodotto immesso sul mercato nel 2029

- 10 euro per ogni prodotto immesso sul mercato nel 2030

Con un limite massimo fissato al 50% del prezzo di vendita.

Questo incremento avrà un impatto sul produttore un anno dopo, quando questi dichiarerà e verserà l’eco-contributo a Refashion e si applica esclusivamente ai produttori di prodotti di fast fashion. I fondi raccolti verranno utilizzati dagli organismi ecologici per finanziare infrastrutture di raccolta e riciclo in paesi al di fuori dell’Unione Europea.

Le società straniere sono soggette a questi obblighi?

Sì, se l’azienda ha sede legale all’estero, ma effettua vendite in Francia, sarà soggetta alle stesse obbligazioni e sanzioni previste dalla legislazione francese, secondo il principio del “produttore esteso”, stabilito dall’articolo L541-10 del codice dell’ambiente francese.

Le società straniere dovranno nominare un rappresentante in Francia a tal fine e non potranno in alcun modo aggirare gli obblighi e le sanzioni stabilite dalla normativa in oggetto.

A cosa prestare attenzione, adesso?

Il Senato sta attualmente esaminando il testo legislativo.

Parallelamente, il governo francese sta pianificando due iniziative aggiuntive: primo, avviare una campagna comunicativa per valorizzare il settore tessile francese e combattere l’ultra fast-fashion; secondo, proporre la creazione di una coalizione internazionale con l’obiettivo di vietare l’esportazione di rifiuti tessili verso i paesi incapaci di gestirli in maniera sostenibile, in linea con le disposizioni della Convenzione di Basilea. è attualmente all’esame del Senato.

Inoltre, è prevista la pubblicazione di un decreto che stabilirà i livelli di produzione, definendo così i produttori interessati da queste misure. Chiaramente questo decreto avrà un impatto estremamente rilevante, perché a seconda dei limiti individuati (si sta discutendo se individuare un limite giornaliero o annuale minimo di capi di abbigliamento) definirà il perimetro di applicazione della norma.

The commercial agent has the right to obtain certain information about the sales of the principal. The Spanish Law on Agency Contracts provides (15.2 LCA) that the agent has the right to demand to see the accounts of the principal in order to verify all matters relating to the commissions due to him. And also, to be provided with the information available to the principal and necessary to verify the amount of such commissions.

This article is in line with the 1986 Commercial Agents Directive, according to which (12.3) the agent is entitled to demand to be provided with all information at the disposal of the principal, particularly an extract from the books of account, which is necessary to verify the amount of commission due to the agent. This may not be altered to the detriment of the commercial agent by agreement.

The question is, does this right remain even after the termination of the agency contract? In other words: once the agency contract is terminated, can the agent request the information and documentation mentioned in these articles and is the Principal obliged to provide it?

In our opinion, the rule does not say anything that limits this right, rather the opposite is to be expected. Therefore, to the extent that there is still any possible commission that may arise from such verification, the answer must be yes. Let us see.

The right to demand the production of accounts exists so that the agent can verify the amount of commissions. And the agent is entitled to commissions for acts and operations concluded during the term of the contract (art. 12 LCA), but also for acts or operations concluded after the termination of the contract (art. 13 LCA), and for operations not carried out due to circumstances attributable to the principal (art. 17 LCA). In addition, the agent is entitled to have the commission accrued at the time when the act or transaction should have been executed (art. 14 LCA).

All these transactions can take place after the conclusion of the contract. Consider the usual situation where orders are placed during the contract but are accepted or executed afterwards. To reduce the agent’s right to be informed only during the term of the contract would be to limit his entitlement to the corresponding commission unduly. And it should be borne in mind that the amount of the commissions during the last five years may also influence the calculation of the client (goodwill) indemnity (art. 28 LCA), so that the agent’s interest in knowing them is twofold: what he would receive as commission, and what could increase the basis for future indemnity.

This has been confirmed, for example, by the Provincial Court (Audiencia Provincial) of Madrid (AAP 227/2017, of 29 June [ECLI:ES:APM:2017:2873A]) which textually states:

[…] art. 15.2 of the Agency Contract Act provides for the right of the agent to demand the exhibition of the Principal’s accounts in the particulars necessary to verify everything relating to the commissions corresponding to him, as well as to be provided with the information available to the Principal and necessary to verify the amount. This does not prevent, […], the agency contract having already been terminated, as this does not imply that commissions would cease to accrue for policies, contracted with the mediation of the agent, which remain in force.

The question then arises as to whether this right to information is unlimited in time. And here the answer would be in the negative. The limitation of the right to receive information would be linked to the statute of limitations of the right to claim the corresponding commission. If the right to receive the commission were undoubtedly time-barred, it could be argued that it would not be possible to receive information about it. But for such an exception, the statute of limitations must be clear, therefore, taking into account possible interruptions due to claims, even extrajudicial ones. In case of doubt, it will be necessary to recognise the right to demand the information, without prejudice to later invoking and recognising the impossibility of claiming the commission if the right is time-barred. And for this we must consider the limitation period for claiming commissions (in general, three years) and that of the right to claim compensation for clientele (one year).

In short: it does not seem that the right to receive information and to examine the principal’s documentation is limited by the term of the agency contract; although, on the other hand, it would be appropriate to analyse the possible limitation period for claiming commissions. In the absence of a clear answer to this question, the right to information should, in our opinion, prevail, without prejudice to the fact that the result may not entitle the claim because it is time-barred.

Scrivi a Geraldo

DAZI US | Clausole contrattuali per la gestione degli aumenti del prezzi

14 Marzo 2025

-

Europa

-

USA

- Distribuzione

- Fisco e tasse

The Brazilian market has not been immune to the protectionist wave of “America First.” If such measures persist over time, they could have a lasting impact on the local economy. Still, a sour lemon can often become a sweet caipirinha in the resilient and optimistic spirit that characterizes both Brazilian society and its entrepreneurs.

As is often the case in the chessboard of global economic geopolitics, a move from one player creates room for another countermove. Brazil reacted with reciprocal trade measures, signaling clearly that it would not accept a position of commercial vulnerability.

This firmer stance — almost unthinkable in earlier years — strengthened Brazil’s image in Europe as a country ready to reposition itself with greater autonomy and pragmatism, opening new doors to international markets. In a world where global value chains are being restructured and reliable trade partners are in high demand, Brazil is increasingly seen not just as a supplier of raw materials, but as a strategic partner in critical industries.

The rapprochement with Europe has been further energized by progress in the Mercosur–European Union Agreement, whose negotiations spanned decades and now seem to be gaining momentum. While the United States embraces a more isolationist commercial posture, Europe is actively diversifying its trade relations — and Brazil, by demonstrating a commitment to clear rules, economic stability, and legal certainty, emerges as a natural candidate to fill that gap.

The Direct Impact of U.S. Tariffs

The trade measures introduced under President Trump primarily affected Brazilian producers of semi-finished steel and primary aluminum, with the removal of long-standing exemptions and quotas. In 2024, Brazil exported US$ 2.2 billion in semi-finished steel to the United States, representing nearly 60% of U.S. imports in that category. In the same year, Brazilian aluminum exports to the U.S. reached US$ 796 million, accounting for 14% of the sector’s total. Losses in exports for 2025 are estimated at around US$ 1.5 billion.

Brazil’s Response and a New Phase

In April 2025, the Brazilian Congress passed a new legal framework for trade retaliation, empowering the Executive Branch to adopt countermeasures in a faster and more technically structured way. The new legislation allows, for example, the automatic imposition of retaliatory tariffs on goods from countries that adopt unilateral measures incompatible with WTO norms; the suspension of tax or customs benefits previously granted under bilateral agreements; the creation of a list of priority sectors for trade defense and diversification of export markets.

Beyond the retaliation itself, the move marked a significant shift in posture: Brazil began positioning itself as an active player in global trade governance, aligning with mid-sized economies that advocate for predictable, balanced, and rules-based trade relations.

An Opportunity for Brazil–Europe Relations

This new stage sets Brazil as a reliable supplier to European industry — not only of raw materials but also of higher-value-added goods, particularly in processed foods, bioenergy, critical minerals, pharmaceuticals, and infrastructure.

Moreover, as US–China tensions drive European companies to seek nearshoring or “friend-shoring” strategies with more predictable partners, Brazil, with its clean energy matrix, large domestic market, and relatively stable institutions, emerges as a strong alternative.

Legal Implications and Strategic Recommendations

This changing landscape brings new opportunities for companies and legal advisors involved in Brazil–Europe investment and trade relations. Particular attention should be paid to:

- Monitoring rules of origin in the Mercosur–EU agreement, especially in sectors requiring supply chain restructuring;

- Reviewing contractual and tax structures for import/export operations, including clauses addressing tariff instability or non-tariff barriers (e.g., environmental or sanitary standards), and clearly defining force majeure events;

- Reassessing distribution and agency agreements in light of the new commercial environment;

- Exploring joint ventures and technology transfer arrangements with Brazilian partners, particularly in bioeconomy, green hydrogen, and mineral processing.

From lemon to caipirinha

The world is becoming more fragmented and competitive, but also more open to realignment. What began as a protectionist blow from the United States has revealed new opportunities for transatlantic cooperation. For Brazil, Europe is no longer just a client: it is poised to become a long-term strategic partner. It is now up to lawyers and businesses on both sides of the Atlantic to turn this opportunity into lasting, mutually beneficial relationships.

Il 2 Aprile 2025 entreranno in vigore le tariffe USA verso i prodotti provenienti dalla UE.

Visto quanto accaduto con le tariffe imposte a Canada e Messico, con una rincorsa di annunci di entrata in vigore e sospensioni e nuovi annunci, è impossibile fare previsioni anche di breve termine.

Occorre prepararsi alla possibilità di imposizione del dazio, che è un evento prevedibile e previsto, che, come tale, va disciplinato nel contratto. Non farlo rischia di costare molto caro, perchè non ci sono argomenti validi per sottrarsi all’adempimento dei contratti già conclusi invocando una situazione di Forza Maggiore (che non sussiste, perché la prestazione non è divenuta oggettivamente impossibile) o di eccessiva onerosità sopravvenuta (in inglese Hardship: anche in caso di aumenti ben oltre il 25%, la giurisprudenza esclude che si possa invocare).

La cautela che si può adottare è quella di negoziare una clausola di aggiornamento dei prezzi, espressamente riferita al caso del dazio, che rispetti i requisiti richiesti dalla giurisprudenza americana per questo tipo di clausole.

Una prima clausola utile può essere la c.d. Escalator o Price Adjustment Clause, con la quale si prevede il diritto di rinegoziare il prezzo nel caso di imposizione di un dazio superiore ad una certa soglia, ad esempio:

PRICE ADJUSTMENT CLAUSE

Triggering Event

A “Triggering Event” shall be deemed to occur if:

- There is an increase in customs duties or the introduction of new trade barriers not previously contemplated, resulting in an increase in the total price of the goods or services by X% or more.

- Such an increase affects either (i) the Buyer directly or (ii) the Seller due to tariffs imposed on its upstream suppliers, materially impacting the cost of performance.

Trigger Mechanism

In the event of a Triggering Event:

- The affected Party shall notify the other Party in writing within thirty (30) days of the effective date of the customs duty change or the introduction of the new trade barrier.

- The notification must include supporting documentation demonstrating the financial impact of the Triggering Event.

Renegotiation Process

Upon receipt of a valid notification, the Parties shall engage in good-faith negotiations for sixty (60) days to agree on an adjusted price that reflects the increased costs.

Failure to Reach an Agreement

If the Parties fail to reach an agreement on the price adjustment within the prescribed sixty (60) days:

Option 1 – Contract Termination: Either Party shall have the right to terminate the contract by providing written notice to the other Party, without liability for damages, except for obligations already accrued up to the termination date.

Option 2 – Third-Party Arbitrator: The Parties shall appoint an independent third-party arbitrator with expertise in international trade and pricing. The arbitrator shall determine a fair market price, which shall be binding on both Parties. The cost of the arbitrator shall be borne equally by both Parties unless otherwise agreed.

***

Un altro possibile strumento in alternativa alla clausola appena vista è c.d. Cost Sharing clause, dove si menziona già l’accordo sulla suddivisione dei costi addizionali conseguenti all’imposizione del dazio, ad esempio:

COST SHARING CLAUSE

Triggering Event

A “Triggering Event” shall be deemed to occur if there is an increase in customs duties or the introduction of new trade barriers not previously contemplated, resulting in an increase in the total price of the goods by [X]% or more. Such an increase will be borne by the Buyer by up to [X]%, while higher increases will be shared equally between the seller and buyer.

***

E’ opportuno che tali clausole vengano calate negli accordi caso per caso, per riflettere al meglio gli scenari che si prevede possano influenzare il prezzo dei prodotti, ossia

- imposizione di dazio in ingresso USA

- imposizione di dazio in ingresso UE

ma anche effetti indiretti, come quello in cui sia il venditore ad invocare la rinegoziazione del prezzo, ad esempio perché il prezzo del prodotto è aumentato a causa del dazio pagato da un suo fornitore a monte della supply chain, nel quale caso è importante identificare quali siano i prodotti rilevanti e documentare gli aumenti derivanti dall’imposizione delle tariffe.

I dazi non li pagano i governi stranieri (come ripetuto più volte da Donald Trump in campagna elettorale) ma le imprese importatrici del paese che emette la tassa sul valore del prodotto importato, ossia, nel caso del recente round di dazi dell’amministrazione Trump, le imprese statunitensi. Allo stesso modo, saranno le imprese canadesi, messicane, cinesi e – probabilmente – europee, che pagheranno i dazi per l’import dei prodotti di provenienza USA, applicati dai rispettivi paesi come misura di ritorsione commerciale nei confronti dei dazi statunitensi.

In questo contesto, si aprono diversi scenari, tutti problematici:

- Per le imprese USA, che versano la tassa di importazione

- Per le imprese straniere che esportano verso gli USA i prodotti tassati, che per effetto dell’aumento dei prezzi vedranno calare i volumi di export

- Per le imprese straniere che importano prodotti dagli USA, perché a loro volta pagheranno i dazi imposti dai loro paesi come ritorsione a quelli americani

- Per i clienti intermedi o finali nei mercati interessati dai dazi, che pagheranno un prezzo più alto sui prodotti importati

L’imposizione del dazio costituisce causa di forza maggiore?

Una prima obiezione frequente della parte colpita dal dazio (può essere il compratore-importatore, oppure chi rivende il prodotto dopo avere pagato il dazio), in questi casi, è quella di invocare la forza maggiore per sottrarsi all’adempimento del contratto, che per effetto del dazio è divenuto troppo oneroso.

L’applicazione del dazio, però, non rientra tra le cause di forza maggiore, poiché non siamo di fronte ad un evento imprevedibile, che comporti l’impossibilità oggettiva di adempiere al contratto. Il compratore / importatore, infatti, può sempre dare adempimento al contratto, con la sola problematica dell’aumento del prezzo.

L’imposizione del dazio costituisce causa di eccessiva onerosità sopravvenuta (hardship)?

Se ricorre una situazione di eccessiva onerosità sopravvenuta dopo la conclusione del contratto (in inglese, harship) la parte colpita ha diritto di chiedere una revisione del prezzo, oppure di terminare il contratto.

Occorre una valutazione caso per caso, che porta a ritenere ricorrente una situazione di hardship se ricorra una situazione straordinaria ed imprevedibile (nel caso dei dazi USA, annunciati da mesi, difficile sostenerlo) e il prezzo, per effetto dell’applicazione del dazio, sia manifestamente eccessivo.

Si tratta di situazioni eccezionali, di rara applicazione, che vanno approfondite sulla base della legge applicabile al contratto. In linea generale le fluttuazioni di prezzo sui mercati internazionali rientrano nel rischio d’impresa e non costituiscono motivo sufficiente per rinegoziare gli accordi conclusi, che restano vincolanti, salvo che le parti non abbiano previsto una clausola di hardship nell’accordo (ne parliamo in seguito).

L’applicazione del dazio comporta un diritto a rinegoziare i prezzi?

I contratti già conclusi, ad esempio gli ordini già accettati e i programmi di fornitura con prezzi concordati per un certo periodo, restando vincolanti e devono essere eseguiti secondo gli accordi originari.

In assenza di clausole specifiche nel contratto, la parte colpita dal dazio è dunque obbligata a rispettare il prezzo precedentemente pattuito e dare adempimento all’accordo.

Le parti sono libere di rinegoziare i futuri contratti, ad esempio

- il venditore può concedere uno sconto per diminuire l’impatto del dazio che colpisce il compratore-importatore, oppure

- il compratore può acconsentire ad un aumento del prezzo per compensare un dazio che il venditore abbia pagato per importare un componente o una semilavorato nel suo paese, per poi esportare il prodotto finito

ma ciò non riguarda la validità degli impegni già contrattualizzati, che restano vincolanti.

La situazione è particolarmente delicata per le imprese che si trovano nel mezzo della catena di fornitura, ad esempio chi importa materie prime o componenti dall’estero (potenzialmente oggetto di dazi, o di doppi dazi in caso di ripetuta importazione ed esportazione) e rivende i prodotti semilavorati o finiti, con ordinativi confermati a lungo termine, o accordi di fornitura a prezzo fisso per un certo periodo. In caso di contratti già conclusi, chi ha importato un prodotto accollandosi il dazio non ha diritto di trasferire il costo sul successivo anello della supply chain, a meno che ciò non fosse espressamente previsto nel contratto con il cliente.

Come tutelarsi nel caso di imposizione di futuri dazi che colpiscano fornitori o clienti stranieri?

E’ consigliabile prevedere espressamente il diritto di rinegoziare i prezzi, se necessario aggiungendo con un addendum all’accordo originario. Il risultato si ottiene, ad esempio, con una clausola che preveda che nel caso di eventi futuri, compresi eventuali dazi, che comportino un aumento del costo complessivo del prodotto sopra una certa soglia (ad esempio il 10%), la parte colpita dal dazio abbia il diritto di avviare una rinegoziazione del prezzo e, in caso di manco accordo, possa recedere dal contratto.

Un esempio di clausola può essere il seguente:

Import Duties Adjustment

“If any new import duties, tariffs, or similar governmental charges are imposed after the conclusion of this Contract, and such measures increase a Party’s costs exceeding X% of the agreed price of the Products, the affected Party shall have the right to request an immediate renegotiation of the price. The Parties shall engage in good faith negotiations to reach a fair adjustment of the contractual price to reflect the increased costs.

If the Parties fail to reach an agreement within [X] days from the affected Party’s request for renegotiation, the latter shall have the right to terminate this Contract with [Y] days’ written notice to other Party, without liability for damages, except for the fulfillment of obligations already accrued.”

“Questo accordo non è solo un’opportunità economica. È una necessità politica“. Nell’attuale contesto geopolitico, caratterizzato da un crescente protezionismo e da importanti conflitti regionali, la dichiarazione di Ursula von der Leyen la dice lunga.

Anche se c’è ancora molta strada da fare prima che l’accordo venga approvato internamente a ciascun blocco ed entri in vigore, la pietra miliare è molto significativa. Ci sono voluti 25 anni dall’inizio dei negoziati tra il Mercosur e l’Unione Europea per raggiungere un testo di consenso. L’impatto sarà notevole. Insieme, i blocchi rappresentano un PIL di oltre 22 mila miliardi di dollari e ospitano oltre 700 milioni di persone.

Vediamo le informazioni più importanti sul contenuto dell’accordo e sul suo stato di avanzamento.

Che cos’è l’accordo EU-Mercosur?

L’accordo è stato firmato come trattato commerciale, con l’obiettivo principale di ridurre le tariffe di importazione e di esportazione, eliminare le barriere burocratiche e facilitare il commercio tra i Paesi del Mercosur e i membri dell’Unione Europea. Inoltre, il patto prevede impegni in aree quali la sostenibilità, i diritti del lavoro, la cooperazione tecnologica e la protezione dell’ambiente.

Il Mercosur (Mercato Comune del Sud) è un blocco economico creato nel 1991 da Brasile, Argentina, Paraguay e Uruguay. Attualmente, Bolivia e Cile partecipano come membri associati, accedendo ad alcuni accordi commerciali, ma non sono pienamente integrati nel mercato comune. D’altra parte, l’Unione Europea, con i suoi 27 membri (20 dei quali hanno adottato la moneta comune), è un’unione più ampia con una maggiore integrazione economica e sociale rispetto al Mercosur.

Cosa prevede l’accordo UE-Mercosur?

Scambio di beni:

- Riduzione o eliminazione delle tariffe sui prodotti scambiati tra i blocchi, come carne, cereali, frutta, automobili, vini e prodotti lattiero-caseari (la riduzione prevista riguarderà oltre il 90% delle merci scambiate tra i blocchi).

- Accesso facilitato ai prodotti europei ad alta tecnologia e industrializzati.

Commercio di servizi:

- Espande l’accesso ai servizi finanziari, alle telecomunicazioni, ai trasporti e alla consulenza per le imprese di entrambi i blocchi.

Movimento di persone:

- Fornisce agevolazioni per visti temporanei per lavoratori qualificati, come professionisti della tecnologia e ingegneri, promuovendo lo scambio di talenti.

- Incoraggia i programmi di cooperazione educativa e culturale.

Sostenibilità e ambiente:

- Include impegni per combattere la deforestazione e raggiungere gli obiettivi dell’Accordo di Parigi sul cambiamento climatico.

- Prevede sanzioni per le violazioni degli standard ambientali.

Proprietà intellettuale e normative:

- Protegge le indicazioni geografiche dei formaggi e dei vini europei e del caffè e della cachaça sudamericani.

- Armonizza gli standard normativi per ridurre la burocrazia ed evitare le barriere tecniche.

Diritti del lavoro:

- Impegno per condizioni di lavoro dignitose e rispetto degli standard dell’Organizzazione Internazionale del Lavoro (OIL).

Quali benefici aspettarsi?

- Accesso a nuovi mercati: Le aziende del Mercosur avranno un accesso più facile al mercato europeo, che conta più di 450 milioni di consumatori, mentre i prodotti europei diventeranno più competitivi in Sud America.

- Riduzione dei costi: L’eliminazione o la riduzione delle tariffe doganali potrebbe abbassare i prezzi di prodotti come vini, formaggi e automobili e favorire le esportazioni sudamericane di carne, cereali e frutta.

- Rafforzamento delle relazioni diplomatiche: L’accordo simboleggia un ponte di cooperazione tra due regioni storicamente legate da vincoli culturali ed economici.

Quali sono i prossimi passo?

La firma è solo il primo passo. Affinché l’accordo entri in vigore, deve essere ratificato da entrambi i blocchi e il processo di approvazione è ben distinto tra loro, poiché il Mercosur non ha un Consiglio o un Parlamento comuni.

Nell’Unione Europea, il processo di ratifica prevede molteplici passaggi istituzionali:

- Consiglio dell’Unione Europea: I ministri degli Stati membri discuteranno e approveranno il testo dell’accordo. Questa fase è cruciale, poiché ogni Paese è rappresentato e può sollevare specifiche preoccupazioni nazionali.

- Parlamento europeo: Dopo l’approvazione del Consiglio, il Parlamento europeo, composto da deputati eletti, vota per la ratifica dell’accordo. Il dibattito in questa fase può includere gli impatti ambientali, sociali ed economici.

- Parlamenti nazionali: Nei casi in cui l’accordo riguardi competenze condivise tra il blocco e gli Stati membri (come le normative ambientali), deve essere approvato anche dai parlamenti di ciascun Paese membro. Questo può essere impegnativo, dato che Paesi come la Francia e l’Irlanda hanno già espresso preoccupazioni specifiche sulle questioni agricole e ambientali.

Nel Mercosur, l‘approvazione dipende da ciascun Paese membro:

- Congressi nazionali: Il testo dell’accordo viene sottoposto ai parlamenti di Brasile, Argentina, Paraguay e Uruguay. Ogni congresso valuta in modo indipendente e l’approvazione dipende dalla maggioranza politica di ciascun Paese.

- Contesto politico: I Paesi del Mercosur hanno realtà politiche diverse. In Brasile, ad esempio, le questioni ambientali possono suscitare accesi dibattiti, mentre in Argentina l’impatto sulla competitività agricola può essere al centro della discussione.

- Coordinamento regionale: Anche dopo l’approvazione nazionale, è necessario garantire che tutti i membri del Mercosur ratifichino l’accordo, poiché il blocco agisce come un’unica entità negoziale.

Seguite questo blog, vi terremo aggiornato sugli sviluppi.

When selling health-related products, the question frequently arises as to which product category, and therefore which regulatory regime, they fall under. This question often arises when distinguishing between food supplements and medicinal products. But in other constellations, too, difficult questions of demarcation arise, which must be answered with a view to legally compliant marketing.

In a highly interesting case, the Administrative Court (Verwaltungsgericht) of Düsseldorf, Germany, recently had to classify a CBD-containing (Cannabidiol) mouth spray that was explicitly advertised by its manufacturer as a “cosmetic” and therefore not suitable for human consumption. The Ingredients of the product were labelled: « Cannabis sativa seed oil, cannabidiol from cannabis extract, tincture or resin, cannabis sativa leaf extract ».

The Product is additionally also labelled as follows: “Cosmetic oral care spray with hemp leaf extract. » The Instructions for use are: « Spray a maximum of 3 sprays a day into the mouth as desired. Spit out after 30 seconds and do not swallow. »

A spray of the Product contains 10 mg CBD. This results in a maximum daily dose of 30 mg CBD as specified by the company.

At the same time, however, it was pointed out that the “consumption” of a spray shot was harmless to health.

The mouth spray could therefore be consumed like a food, but was declared as a “cosmetic”. This is precisely where the court had to examine whether the prohibition order based on food law was lawful.

For the definition of cosmetic products Article 2 sentence 4 lit. e) Regulation (EC) No. 178/2002 refers to Directive 76/768/EEC. This was replaced by Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009. Cosmetic products are defined in Article 2(1)(a) as follows: “‘cosmetic product’ means any substance or mixture intended to be placed in contact with the external parts of the human body (epidermis, hair system, nails, lips and external genital organs) or with the teeth and the mucous membranes of the oral cavity with a view exclusively or mainly to cleaning them, perfuming them, changing their appearance, protecting them, keeping them in good condition or correcting body odours ”.

Here too, it is not the composition of the product that is decisive, but its intended purpose, which is to be determined on the basis of objective criteria according to general public opinion based on concrete evidence.

According to the system of Regulation (EC) No. 178/2002, Article 2 sentence 1 first defines foodstuffs in general and then excludes cosmetic products under sentence 4 lit. e). According to the definition in Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009, cosmetic products must have an exclusive or at least predominant cosmetic purpose. It can be concluded from this system that the exclusivity or predominance must be positively established. If it is not possible to determine which purpose predominates, the product is a foodstuff.

The Düsseldorf Administrative Court had to deal with this question in the aforementioned legal dispute brought by the distributor against an official prohibition order in the form of a so-called general ruling („Allgemeinverfügung“). By notice dated July 11, 2020, the competent authority issued a general ruling prohibiting the marketing of foodstuffs containing “cannabidiol (as ‘CBD isolates’ or ‘hemp extracts enriched with CBD’)” in their urban area. The company, based in this city, offered the mouth spray described above.

In a ruling dated 25.10.2024 (Courts Ref. : 26 K 2072/23), the court dismissed the company’s claim. The court’s main arguments were :

- Classification as food: the CBD spray was correctly classified as food by the authority, as it was reasonable to expect that it could be swallowed despite indications to the contrary. According to an objective perception of the market, there is a now established expectation of an average informed, attentive and reasonable consumer to the effect that CBD oils are intended as “lifestyle” products for oral ingestion, from which consumers hope for positive health effects The labelling as “cosmetic” was refuted by the objective consumer expectations and the nature of the application.

- No medicinal product status: Due to the low dosage in this case (max. 30 mg CBD per day), the product was not classified as a functional medicinal product, as there was no sufficiently proven pharmacological effect.

- Legal basis of the injunction: The prohibition of the sale of the products by the defendant was based on a general order, which was confirmed as lawful by the court.

In the ruling, the court emphasizes the objective consumer expectation and clarifies that products cannot be exempted from a different regulatory classification by the authorities or the courts solely by their labelling.

Conclusion: The decision presented underlines the considerable importance of the “correct” classification of a health product in the respective legal product category. In addition to the classic distinction between foodstuffs (food supplements) and medicinal products, comparable issues also arise with other product types. In this case in the constellation of cosmetics versus food – combined with the special legal component of the use of CBD.

Commercial agents have specific regulations with rights and obligations that are “mandatory”: those who sign an agency contract cannot derogate from them. Answering whether an influencer can be an agent is essential because, if he or she is an agent, the agent regulations will apply to him or her.

Let’s take it one step at a time. The influencer we will talk about is the person who, with their actions and comments (blogs, social media accounts, videos, events, or a bit of everything), talks to their followers about the advantages of certain products or services identified with a certain third-party brand. In exchange for this, the influencer is paid.[1]

A commercial agent is someone who promotes the contracting of others’ products or services, does so in a stable way, and gets paid in return. He or she can also conclude the contract, but this is not essential.

The law imposes certain obligations and guarantees rights to those signing an agency contract. If the influencer is considered an “agent”, he or she should also have them. And there are several of them: for example, the duration, the notice to be given to terminate the contract, the obligations of the parties… And the most relevant, the right of the agent to receive compensation at the end of the relationship for the clientele that has been generated. If an influencer is an agent, he would also have this right.

How can an influencer be assessed as an agent? For that we must analyse two things: (a) the contract (and be careful because there is a contract, even if it is not written) and (b) how the parties have behaved.

The elements that, in my opinion, are most relevant to conclude that an influencer is an agent would be the following:

a) the influencer promotes the contracting of services or the purchase of products and does so independently.

The contract will indicate what the influencer must do. It will be clearer to consider him as an agent if his comments encourage contracting: for example, if they include a link to the manufacturer’s website, if he offers a discount code, if he allows orders to be placed with him. And if he does so as an independent “professional”, and not as an employee (with a timetable, means, instructions).

It may be more difficult to consider him as an agent if he limits himself to talking about the benefits of the product or service, appearing in advertising as a brand image, and using a certain product, and speaking well of it. The important thing, in my opinion, is to examine whether the influencer’s activity is aimed at getting people to buy the product he or she is talking about, or whether what he or she is doing is more generic persuasion (appearing in advertising, lending his or her image to a product, carrying out demonstrations of its use), or even whether he or she is only seeking to promote himself or herself as a vehicle for general information (for example, influencers who make comparisons of products without trying to get people to buy one or the other). In the first case (trying to get people to buy the product) it would be easier to consider it as an “agent”, and less so in the other examples.

b) this “promotion” is done in a continuous or stable manner.

Be careful because this continuity or stability does not mean that the contract has to be of indefinite duration. Rather, it is the opposite of a sporadic relationship. A one-year contract may be sufficient, while several unconnected interventions, even if they last longer, may not be sufficient.

In this case, influencers who make occasional comments, who intervene with isolated actions, who limit themselves to making comparisons without promoting the purchase of one or the other, and even if all this leads to sales, even if their comments are frequent and even if they can have a great influence on the behavior of their followers, would be excluded as agents.

c) they receive remuneration for their activity.

An influencer who is remunerated based on sales (e.g., by promoting a discount code, a specific link, or referring to your website for orders) can more easily be considered as an agent. But also, if he or she only receives a fixed amount for their promotion. On the other hand, influencers who do not receive any remuneration from the brand (e.g. someone who talks about the benefits of a product in comparison with others, but without linking it to its promotion) would be excluded.

Conclusion

The borderline between what qualifies an influencer as an agent and what does not can be very thin, especially because contracts are often not unambiguous and sometimes their services are multiple. The most important thing is to carefully analyse the contract and the parties’ behaviour.

An influencer could be considered a commercial agent to the extent that his or her activity promotes the contracting of the product (not simply if he or she carries out informative or image work), that it is done on a stable basis (and not merely anecdotal or sporadic) and in exchange for remuneration.

To assess the specific situation, it is essential to analyse the contract (if it is written, this is easier) and the parties’ behaviour.

In short, to draw up a contract with an influencer or, if it has already been signed, but you want to conclude it, you will have to pay attention to these elements. As an influencer you may have a strong interest in being considered an agent at the end of the contract and thus be entitled to compensation, while as employer you will prefer the opposite.

FINAL NOTE. In Spain and at the date of this comment (9 June 2024) I am not aware of any judgement dealing with this issue. My proposal is based on my experience of more than 30 years advising and litigating on agency contracts. On the other hand, and as far as I know, there is at least one judgment in Rome (Italy) dealing with the matter: Tribunale di Roma; Sezione Lavoro 4º, St. 2615 of 4 March 2024; R. G. n. 38445/2022.

La legge contro l’ultra fast-fashion è stata concepita per fronteggiare la crescente preoccupazione riguardante l’impatto ambientale, economico e sulla salute provocato dall’inondazione del mercato con tessuti e accessori di moda da parte di giganti come SHEIN, TEMU, PRIMARK e altri. Queste aziende, spesso trascurando le conseguenze delle loro pratiche, hanno contribuito significativamente all’incremento delle emissioni di gas serra attribuite all’industria tessile, che ora si stima essere responsabile per circa l’8% del totale globale.

In un contesto dove la produzione globale di abbigliamento ha visto un raddoppio in soli 14 anni e la durata di vita degli indumenti si è ridotta di un terzo, il marchio SHEIN ha registrato una crescita esponenziale del 100% tra il 2021 e il 2022, evidenziando ulteriormente la problematica del fast fashion che domina il mercato francese, nonostante in alcuni settori si stia vivendo una rinascita dell’artigianalità e del design made in France.

La risposta delle autorità francesi si è concretizzata nel disegno di legge n. 2129, volto a ridurre l’impatto ambientale dell’industria tessile, proposto da un deputato del Governo e adottato all’unanimità dall’Assemblea Nazionale il 14 marzo 2024, che nelle prossime settimane verrà esaminato dal Senato con una procedura accelerata, prima della definitiva adozione.

Questa normativa si propone di sensibilizzare i consumatori sull’importanza della sobrietà e della sostenibilità nell’industria della moda, promuovendo pratiche di riutilizzo, riparazione, e riciclaggio, e introducendo penalizzazioni per i produttori che non rispettano determinati standard ecologici.

Di seguito le misure principali.

1. Definizione legale di fast-fashion e obblighi informativi