-

Francia

Francia – La Corte di Giustizia CE estende la tutela degli agenti di commercio e il diritto all’indennità di fine rapporto

4 Agosto 2020

- Agenzia

- Distribuzione

Sotto la presidenza vietnamita dell’Associazione delle nazioni del Sud-est asiatico (ASEAN), dopo otto anni di negoziati i dieci Stati membri dell’ASEAN (Brunei, Cambogia, Filippine, Indonesia, Laos, Malesia, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailandia, Vietnam) il 15 novembre 2020 hanno firmato un clamoroso accordo di libero scambio (FTA) con Cina, Corea del Sud, Giappone, Australia e Nuova Zelanda, denominato Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

La comunità economica dell’ASEAN è un’area di libero scambio avviata nel 2015 tra i suddetti dieci membri dell’omonima associazione, che comprende un PIL aggregato di 2,6 trilioni di dollari e oltre 622 milioni di persone. L’ASEAN è il principale partner commerciale della Cina, con l’Unione Europea scivolata al secondo posto.

A differenza dell’Eurozona e dell’Unione Europea, l’ASEAN non ha una moneta unica, né istituzioni comuni, come la Commissione Europea, il Parlamento e il Consiglio. Analogamente a quanto accade nell’UE, tuttavia, un singolo membro detiene una presidenza a rotazione.

Singoli Paesi ASEAN, come Vietnam e Singapore, hanno recentemente stipulato accordi di libero scambio con l’Unione Europea, mentre l’intero blocco ASEAN aveva e ha tuttora in essere i cosiddetti accordi “più uno” con altri Paesi dell’area, ovvero la Repubblica Popolare Cinese, Hong Kong, la Repubblica di Corea,, il Giappone, l’India e l’Australia e la Nuova Zelanda insieme.

Ad eccezione dell’India, tutti gli altri Paesi con accordi “più uno” con l’ASEAN fanno ora parte dell’RCEP, che supererà progressivamente i singoli FTA attraverso l’armonizzazione delle regole, soprattutto quelle relative all’origine dei prodotti.

I negoziati RCEP sono accelerati con la decisione degli Stati Uniti d’America di ritirarsi dal Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement (TPP) con l’elezione del presidente Trump nel 2016 (anche se vale la pena di ricordare che anche gran parte del partito democratico degli Stati Uniti si era ai tempi opposta al TPP). Il TPP sarebbe stato quindi il più grande accordo di libero scambio di sempre e, come suggerisce il nome, avrebbe messo insieme dodici nazioni affacciate sull’Oceano Pacifico, ossia Australia, Brunei, Canada, Cile, Giappone, Malesia, Messico, Nuova Zelanda, Perù, Singapore, Vietnam e appunto Stati Uniti. Con l’esclusione di questi ultimi, gli altri undici hanno comunque firmato un accordo simile, denominato Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Il CPTPP è stato tuttavia ratificato solo da sette dei suoi firmatari e chiaramente non ne fa parte la più grande economia e partner più significativo di tutti. Allo stesso tempo, sia l’abortito TPP, sia il CPTPP escludono enfaticamente la Cina.

Il peso del RCEP è quindi evidentemente maggiore, in quanto nei Paesi firmatari, che rappresentano circa il 30% del PIL mondiale, vivono 2,1 miliardi di persone. E la porta per l’India con i suoi 1,4 miliardi di persone e 2,6 trilioni di dollari di PIL rimane aperta, hanno affermato gli altri membri.

Come la maggior parte degli accordi di libero scambio, l’obiettivo dell’RCEP è abbassare le tariffe, facilitare gli scambi di beni e servizi e promuovere gli investimenti. L’accordo affronta brevemente la tutela dei diritti di proprietà intellettuale, ma non fa menzione della tutela dell’ambiente e dei diritti dei lavoratori. I suoi firmatari comprendono economie molto avanzate, come quella di Singapore, e piuttosto povere, come quella della Cambogia.

Il significato dell’RCEP in questo momento è probabilmente più simbolico che tangibile. Anche se si stima che circa il 90% delle tariffe sarà abolito, ciò avverrà solo in un periodo di venti anni dall’entrata in vigore, cosa che accadrà solo dopo la ratifica. Inoltre, il settore dei servizi e soprattutto quello agricolo non rappresentano il fulcro dell’accordo e pertanto saranno ancora soggetti a barriere, regole e restrizioni nazionali. Ciononostante, si stima che, anche in questi tempi di pandemia, l’RCEP contribuirà annualmente al PIL mondiale per circa 40 miliardi di dollari in più rispetto al CPTPP (186 miliardi di dollari contro 147 miliardi di dollari) per dieci anni consecutivi.

Il suo impatto immediato è geopolitico. Sebbene i firmatari non siano affatto alleati di ferro (si pensi alle controversie territoriali sul Mar Cinese Meridionale, per esempio), il messaggio è chiaro:

- La maggior parte di questa parte del mondo ha affrontato la pandemia di Covid-19 molto bene, ma non può permettersi di aprire le sue frontiere a europei e americani in tempi brevi, per timore che il virus si diffonda di nuovo. Deve quindi cercare di appianare le tensioni interne, se vuole vedere nelle sue economie alcuni segnali positivi dati dal commercio privato, oltre alla spesa pubblica in deficit (non sempre “buona”). La maggior parte di questi Paesi fa molto affidamento sui talenti, sui turisti, sui beni, sui servizi e persino sul supporto strategico e militare dell’Occidente, ma è realista sul fatto che, a meno che il tanto pubblicizzato vaccino non funzioni molto bene e molto presto, l’Occidente lotterà con questo coronavirus per lunghi mesi, se non anni.

- Il multilateralismo è fondamentale e l’isolazionismo è pericoloso. Il blocco ASEAN e il duo Australia-Nuova Zelanda lavorano esattamente in questa direzione pacifica e favorevole agli affari.

Il sito web ufficiale dell’ASEAN (https://asean.org/?static_post=rcep-regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership) è molto chiaro al riguardo e afferma, infatti, che:

L’RCEP fornirà un quadro volto ad abbassare le barriere commerciali e garantire un migliore accesso al mercato di beni e servizi per le imprese della regione, attraverso:

- Il riconoscimento della centralità dell’ASEAN nell’architettura economica regionale e degli interessi dei partner dell’ASEAN nel potenziamento dell’integrazione economica e nel rafforzamento della cooperazione economica tra i Paesi partecipanti agli FTA;

- La facilitazione del commercio e degl’investimenti e maggiore trasparenza nelle relazioni commerciali e di investimento tra i Paesi partecipanti, nonché maggiore coinvolgimento delle PMI nelle catene di valore globali e regionali; e

- L’ampliamento degli impegni economici dell’ASEAN con i suoi partner.

L’RCEP riconosce l’importanza dell’inclusività, in particolare per consentire alle PMI di sfruttare l’accordo e far fronte alle sfide derivanti dalla globalizzazione e dalla liberalizzazione del commercio. Le PMI (comprese le microimprese) costituiscono più del 90% delle imprese dei firmatari dell’RCEP e sono importanti per lo sviluppo endogeno dell’economia di ogni Paese. Allo stesso tempo, l’RCEP è volto a fornire politiche economiche regionali eque a vantaggio sia dell’ASEAN, sia dei suoi partner.

Tuttavia, il momento è favorevole anche per le imprese dell’UE. Come ricordato, l’UE ha in essere accordi di libero scambio con Singapore, Corea del Sud, Vietnam, un accordo di partenariato economico con il Giappone e sta negoziando separatamente sia con l’Australia, sia con la Nuova Zelanda.

In generale, tutti questi accordi creano regole comuni per tutti gli attori coinvolti, rendendo così più semplice per le aziende commerciare in diversi territori. Con le avvertenze già rapidamente enucleate sull’entrata in vigore e sulle regole di origine, i Paesi che hanno firmato un accordo di libero scambio con l’UE e l’RCEP, in particolare Singapore, un importante hub di lingua inglese, che si colloca al primo posto in Asia orientale nell’indice dello Stato di diritto (terzo nella regione dopo Nuova Zelanda e Australia e dodicesimo in tutto il mondo: https://worldjusticeproject.org/sites/default/files/documents/Singapore%20-%202020%20WJP%20Rule%20of%20Law%20Index%20Country%20Press%20Release.pdf), potrebbero collegare entrambe le regioni e facilitare il commercio globale anche in questo difficile periodo storico.

Under French law, terms of payment of contracts of sale or of services (food excluded) are strictly regulated (art. L441-10.I Commercial code) as follows:

- Unless otherwise agreed between the parties, the standard time limit for settling the sums due may not exceed 30 days.

- Parties can agree on a time of payment which cannot exceed 60 days after the date of the invoice.

- By way of derogation, a maximum period of 45 days from end of the month after the date of the invoice may be agreed between the parties, provided that this period is expressly stipulated by contract and that it does not constitute a blatant abuse with respect to the creditor (e.g. could be in fact up to 75 days after date of issuance).

The types of international contracts concluded with a French party can be:

(a) An international sales contract governed by French law (or to the national law of a country where CISG is in force), and which does not contractually exclude the Vienna Convention of 1980 on the International Sale of Goods (CISG)

In this case the parties may be freed from the domestic mandatory payment time limits, by virtue of the superiority of CISG over French domestic rules, as stated by public authorities,

(b) An international contract (sale, service or otherwise) concluded by a French party with a party established in the European Union and governed by the law of this other European State,

In this case the parties could be freed from the French domestic mandatory payment time limits, by invoking the rules of this member state law, in accordance with the EU directive 2011/7;

(c) Other international contracts not belonging to (a) or (b),

In these cases the parties might be subject to the French domestic mandatory payment maximum ceilings, if one considers that this rule is an OMR (but not that clearly stated).

Can a foreign party (a purchaser) agree with a French party on time limit of payment exceeding the French mandatory maximum ceilings (for instance 90 days)?

This provision is a public policy rule in domestic contracts. Failing to comply with the payment periods provided for in this article L. 441-10, any trader is liable to an administrative fine, up to a maximum amount of € 75,000 for a natural person and € 2,000,000 for a company. In the event of reiteration the maximum of the fine is raised to € 150,000 for a natural person and € 4,000,000 for a legal person.

There is no express legal special derogatory rule for international contracts (except one very limited to specific intra UE import / export trading). This being said, the French administration (that is to say the Government, the French General Competition and Consumer protection authority, “DGCCRF” or the Commission of examination of the commercial practices, “CEPC”) shows a certain embarrassment for the application of this rule in an international context because obviously it is not suitable for international trade (and is even counterproductive for French exporters).

International sales contract can set aside the maximum payment ceilings of article L441-10.I

Indeed, the Government and the CEPC have identified a legal basis authorizing French exporters to get rid of the maximum time limit imposed by the French commercial code: this is the UN Convention on the international sale of goods of 1980 (aka “CISG”) applying to contracts of supply of (standard or tailor-made) goods (but not services). They invoked the fact that CISG is an international treaty which is a higher standard than the internal standards of the Civil Code and the Commercial Code: it is therefore necessary to apply the CISG instead of article L441-10 of the Commercial Code.

- In the 2013 ministerial response, (supplemented by another one in 2014) the Ministry of Finance was very clear: “the default application of the CISG rules […] therefore already allows French traders to grant their foreign customers payment terms similar to those offered by their international competitors”.

- In its Statement of 2016 (n°16.12), the CEPC went a little further in the reasoning by specifying that CISG poses as a rule that payment occurs at the time of the delivery of the goods, except otherwise agreed by the parties (art. 58 & 59), but does not give a maximum ceiling. According to this Statement, it would therefore be possible to justify that the maximum limit of the Commercial Code be set aside.

The approach adopted by the Ministry of Finance and by the CEPC (which is a kind of emanation of this Ministry) seems to be a considerable breach in which French exporters and their foreign clients can plunge into. This breach is all the easier to use since CISG applies by default as soon as a sales contract is subject to French law (either by the express choice of the parties, or by application of the conflict of law rules by the judge subsequently seized). In other words, even if controls were to be carried out by the French administration on contracts which do not expressly target the CISG, it would be possible to invoke this “CISG open door”.

This ground seems also to be usable as soon as the international sale contract is governed by the national law of a foreign country … which has also ratified CISG (94 countries). But conversely, if the contract expressly excludes the application of CISG, the solution proposed by the administration will close.

For other international contracts not governed by CISG, is this article L441-10.I an overriding mandatory rule in the international context?

The answer is ambiguous. The issue at stake is: if art. L441-10 is an overriding mandatory rule (“OMR”), as such it would still be applied by a French Judge even if the contract is subject to foreign law.

Again the Government and the CEPC took a stance on this issue, but not that clear.

- In its 2013 ministerial response, the Ministry of Finance statement was against the OMR qualification when he referred to «foreign internal laws less restrictive than French law [that] already allows French traders to grant their foreign customers payment terms similar to those offered by their international competitors”.

- The CEPC made another Statement in 2016 (n°1) to know whether or not these ceilings are OMRs in international contracts. A distinction should be made as regards the localization of the foreign party:

– For intra-EU transactions, the CEPC put into perspective these maximum payment terms with the 2011/7 EU directive on the harmonization of payment terms which authorizes other European countries to have terms of payment exceeding 60 days (art 3 §5). Therefore article L441-10.I could not be seen as OMR because it would conflict with other provisions in force in other European countries, also respecting the EU directive which is a higher standard than the French Commercial Code.

– For non intra EU transactions, CEPC seems to consider article L441-10.I as an OMR but the reasoning was not really strong to say straightforwardly that it is per se an OMR.

To conclude on the here above, (except for contracts – sales excluded – concluded with a non-EU party, where the solution is not yet clear), foreign companies may negotiate terms of payment with their French suppliers which are longer than the maximum ceilings set by article L441 – 10, provided that it is not qualified as an abuse of negotiation (to be anticipated in specific circumstances or terms in the contract to show for instance counterparts, on a case by case basis) and having in mind that, with this respect, French case law is still under construction by French courts.

Riassunto – In un contratto con controparte straniera o nelle condizioni generali di vendita o di acquisto internazionale è frequente l’utilizzo della clausola di scelta del foro competente e della legge applicabile. Spesso la scelta, però, non viene fatta in modo consapevole e può portare a risultati contrari agli interessi della parte che la predispone. Vediamo in questo articolo come procedere a questa scelta in modo corretto ed utile.

La clausola del contratto che disciplina la modalità di risoluzione delle controversie e la legge applicabile al rapporto è spesso chiamata la “midnight clause”, facendo riferimento al fatto che in molti modelli di contratto questa clausola è tra le ultime del documento e viene dunque discussa al termine delle trattative, spesso a tarda notte, quando le parti sono esauste e desiderose di firmare il contratto.

I casi ricorrenti sono due: nel primo, la decisione viene presa con noncuranza e in maniera frettolosa, posto che le parti ritengono di avere già raggiunto l’accordo sulle questioni importanti del contratto e non danno peso – a torto – alla previsione sulla risoluzione delle liti.

Nel secondo caso accade il contrario: sulla decisione del giudice competente e della legge applicabile si genera un muro contro muro, con entrambe le parti risolute – in genere per una questione di principio e di diffidenza verso le norme straniere – ad imporre la giurisdizione nel proprio paese e l’applicabilità della legge nazionale.

Entrambi gli scenari sono molto delicati, perché espongono al rischio di decisioni sbagliate o di pessimi compromessi, che possono giungere a vanificare la futura possibilità di agire in giudizio.

E’ fondamentale che questa clausola venga affrontata in modo consapevole e non improvvisato: vediamo alcune considerazioni da tenere a mente al momento di scegliere la giurisdizione e la legge applicabile.

Il giudice straniero non è un tabù

Facciamo un esempio pratico: un contratto tra una società italiana e una controparte cinese.

Per lungo tempo gli stranieri sono stati, giustamente, terrorizzati dall’idea di rivolgersi al giudice cinese, che era un funzionario statale proveniente da altre amministrazioni pubbliche, di assai dubbia imparzialità, politicizzato e in genere del tutto incompetente.

La situazione oggi è cambiata e, quantomeno nelle città oggetto da anni di investimenti internazionali, il livello di preparazione della magistratura è certamente migliorato, i costi di un contenzioso sono tutto sommato contenuti, i tempi di un giudizio di primo grado rapidi (circa 6 mesi) e la possibilità di un equo giudizio, se ben difesi da un avvocato competente, certamente alla portata.

Si può – e si deve- dunque valutare l’opzione di prevedere la giurisdizione cinese in contratto, considerando i futuri scenari possibili in caso di future vertenze.

Lo stesso ragionamento va fatto, caso per caso, con altri paesi: prima di rifiutare la scelta di giurisdizione nel paese straniero, occorre valutare quali siano i pro e i contro di un’eventuale azione legale in Italia e quale sarebbe la situazione se la causa venisse instaurata presso un giudice del paese straniero in cui ha sede la controparte.

Tra gli elementi da valutare vi sono i seguenti:

- L’efficienza del sistema giudiziario del paese straniero

- I costi del procedimento giudiziario (tasse)

- I costi legali (onorari degli avvocati del paese straniero)

- Tempi e costi del procedimento per ottenere il riconoscimento della sentenza italiana nel paese straniero

Attaccare in trasferta, difendersi in casa

La scelta sul foro competente può essere, in primo luogo, una scelta tattica: se è probabile che eventuali futuri contenziosi siano attivati dalla controparte, usando una metafora calcistica, optare per il giudice italiano concede la il vantaggio del fattore campo.

Per una società straniera, infatti, sarà più difficile iniziare la causa e gestire un contenzioso in Italia, con necessità di essere assistita da legali italiani, di applicare una legge con cui non ha familiarità e di sostenere costi di viaggio per comparire avanti ad un tribunale italiano.

Se invece, al contrario, è probabile che sia la società italiana a doversi attivare con un’azione giudiziaria (ad esempio per il pagamento del prezzo, o per ottenere l’adempimento o la risoluzione del contratto) “giocare in attacco” presso il giudice del luogo in cui viene eseguito il contratto (e ha sede, in genere, la controparte straniera) può comportare molti vantaggi, tra i quali quello di ottenere in tempi rapidi una sentenza direttamente eseguibile nel paese in cui ha sede la controparte.

La clausola “asimmetrica”

Una soluzione intermedia, che consente di fruire dei benefici sia della giurisdizione italiana, sia di quella del paese in cui ha sede la controparte straniera, è la cosiddetta clausola “asimmetrica”.

Tali clausole prevedono la facoltà di una sola parte di introdurre la lite sia davanti al giudice indicato nel contratto (ad esempio Italiano), sia dinanzi a quello che sarebbe competente secondo i criteri ordinari di giurisdizione, ad esempio il foro della sede della parte straniera (ad esempio, i giudici della città di Pechino).

L’altro contraente non ha questa facoltà di scelta ed è quindi obbligato a promuovere eventuali controversie soltanto dinanzi all’autorità giudiziaria contrattualmente indicata (il giudice italiano).

Mentre questo tipo clausola è generalmente considerato valido in Italia e nella UE, è bene verificarne la legittimità nel caso si applichi al contratto una legge straniera.

Dove andrà eseguita la sentenza?

Uno dei fattori importanti nella decisione sul foro è certamente il luogo di esecuzione della sentenza: occorre, cioè, considerare quali tipi di vertenze si potranno generare nella relazione commerciale e dove sarà possibile eseguire la sentenza ottenuta, se in Italia o nel paese in cui ha sede la controparte.

Rimaniamo sull’esempio del contratto con una parte cinese.

Nella maggioranza dei casi la parte cinese ha asset (beni e crediti aggregabili) solo in Cina e se la sentenza favorevole alla parte italiana non venisse spontaneamente adempiuta (scenario molto frequente) si renderebbe necessario procedere all’esecuzione forzata, appunto, in Cina.

Per questa ragione prevedere la giurisdizione del giudice italiano può essere una mossa controproducente, che obbliga prima a radicare una causa in Italia, spesso con tempi molto lunghi, e poi a chiedere il riconoscimento della sentenza italiana nella Repubblica Popolare Cinese: ciò è possibile grazie al Trattato per l’assistenza giudiziaria in materia civile del 1991, ma il procedimento è molto burocratico, richiede la traduzione in cinese e la legalizzazione della sentenza e di tutti i documenti e nel corso del giudizio di riconoscimento la parte cinese farà tutto il possibile per complicare e ritardare il riconoscimento della decisione.

Il risultato è che, anziché ottenere una sentenza eseguibile in Cina in pochi mesi (ricorrendo al giudice Cinese) si perdono diversi anni, incorrendo in costi molto superiori e con l’amara sorpresa, anche questa purtroppo frequente, che al termine della procedura di riconoscimento la controparte cinese risulta irreperibile o insolvente o non è comunque possibile reperire beni da aggredire esecutivamente.

Testimoni, perizie e documenti

Un altro fattore da tenere presente è legato alla natura del contratto e al luogo di svolgimento delle prestazioni delle parti: in caso di contratto con obbligazioni da svolgere in Cina (come ad esempio la gestione di un punto vendita, lo svolgimento di attività promozionale da parte di un agente o concessionario, la fornitura o assemblaggio di prodotti) l’istruttoria della causa, ossia l’audizione dei testimoni, l’eventuale incarico ad un perito di esaminare un prodotto, l’analisi dei documenti necessari per decidere la causa, può essere agevole presso il giudice Cinese, mentre sarebbe estremamente difficile, se non del tutto impossibile e certamente anti-economica, presso un foro Italiano. E viceversa, naturalmente.

Tutela urgente e Misure cautelari

Può accadere, infine, che sia urgente ricorrere al giudice per avere tutela di situazioni che non possono attendere i tempi di una causa ordinaria: rimanendo all’esempio del contratto con la Cina un caso tipico è quello del concessionario o franchisee che opera in concorrenza sleale con il produttore o franchisor, vendendo merce contraffatta o rifiutando di restituire negozi e materiali di proprietà del produttore/ franchisor dopo la cessazione del contratto.

In tali casi avere la possibilità di adire il giudice cinese con richiesta di un procedimento cautelare, ossia una misura urgente finalizzata a far cessare il comportamento illegittimo in corso, è fondamentale. Ciò è possibile se il contratto prevede la giurisdizione cinese o un arbitrato con sede in Cina, mentre l’eventuale previsione in contratto della giurisdizione italiana precluderebbe il ricorso ad un’azione legale urgente in Cina, con la conseguenza, molto grave, che non sarebbe possibile agire in modo efficace e tempestivo per limitare i gravi danni di avviamento commerciale ed immagine.

Stesso giudice, stessa legge

Un compromesso per rompere lo stallo nelle trattative è spesso quello di scegliere il giudice di un paese e la legge dell’altro, quando non addirittura di prevedere il giudice di un paese terzo e la legge di un paese ancor diverso.

Soluzioni “creative” di questo tipo sono assolutamente da evitare: è bene che il giudice adito sia quello di uno dei paesi delle parti (idealmente quello di esecuzione della sentenza, come detto sopra) e che il Giudice possa decidere la causa sulla base della normativa con cui Giudice e avvocati delle parti hanno familiarità.

In caso contrario è necessario che le norme della legge applicabile debbano essere indicate dalle parti (raramente in accordo tra loro) o che venga nominato un consulente esperto della legge in questione, con notevole incremento dei costi di lite, complicazione della trattazione della causa e allungamento dei tempi.

Qualche esempio

Sottoporre un NDA – Non Disclosure Agreement – con una società con sede negli USA o in Cina alla legge italiana e alla giurisdizione italiana può risultare un’arma spuntata: in caso sia necessario agire in giudizio e ottenere la cessazione urgente di comportamenti illegittimi di utilizzo delle informazioni riservate è molto più rapido ed efficace agire direttamente presso il foro in cui ha sede la controparte o con un arbitrato, ottenendo un provvedimento direttamente esecutivo nel paese.

Se il contratto è una vendita internazionale e il compratore ha sede in un paese all’interno della UE può essere utile una clausola “asimmetrica”, che consenta, ad esempio, di adire il giudice italiano per ottenere un decreto ingiuntivo (che una volta definitivo si può eseguire direttamente all’interno dello spazio giuridico comunitario) ma anche di radicare la causa presso il giudice del paese in cui ha sede il convenuto, nel caso in cui ciò risultasse preferibile perché il procedimento è rapido e i costi contenuti (per approfondire l’argomento, vedi questo post sul Recupero del Credito all’estero).

Se la controparte ha sede in un paese in cui l’accesso alla giustizia ordinaria è problematico o non dà garanzie di un processo imparziale in tempi certi, si può valutare l’inserimento di una clausola arbitrale, previa verifica che un lodo arbitrale internazionale sia automaticamente eseguibile perché lo stato in cui ha sede la controparte è membro della Convenzione di New York del 1958 sul riconoscimento e l’esecuzione dei lodi arbitrali stranieri.

Conclusioni

La clausola di scelta del foro (e della legge applicabile) è una clausola fondamentale di un contratto (o di condizioni generali di contratto) internazionale. La scelta del foro deve essere compiuta in maniera consapevole e caso per caso, in base al paese di esecuzione del contratto e alla tipologia di controversie che si prevede ne possa derivare; non sempre il Giudice italiano è la scelta migliore e può essere opportuno, in alcuni casi, scegliere la giurisdizione straniera oppure prevedere una clausola arbitrale. Il mio consiglio è di predisporre i contratti internazionali insieme ad un consulente specializzato, evitando l’uso di un unico modello per tutti i paesi in cui opera l’impresa.

Possiamo aiutarti?

Sommario – Secondo la giurisprudenza francese, un agente è soggetto alla tutela dello status giuridico di agente di commercio e ha quindi diritto a un’indennità di fine rapporto solo se in potere di negoziare liberamente il prezzo e le condizioni dei contratti di vendita. La Corte di Giustizia Europea ha recentemente stabilito che tale condizione non è conforme al diritto europeo. Tuttavia, i preponenti potrebbero ora prendere in considerazione altre opzioni per limitare o escludere l’indennità di fine rapporto.

Dire che la sentenza della Corte di giustizia europea del 4 giugno 2020 (n°C828/18, Trendsetteuse / DCA) fosse molto attesa sia dagli agenti francesi che dai loro preponenti è un eufemismo.

La richiesta fatta alla Corte di Giustizia CE

La questione posta dal Tribunale Commerciale di Parigi il 19 dicembre 2018 alla CGCE riguardava la definizione dello status di agente di commercio affinché quest’ultimo potesse beneficiare della Direttiva CE del 18 dicembre 1986 e di conseguenza dell’articolo L134 e seguenti del Codice Commerciale. La questione preliminare consisteva nel sottoporre alla CGCE la definizione adottata dalla Corte di Cassazione e da molte Corti d’Appello, a partire dal 2008: il beneficio dello status di agente di commercio è stato negato a qualsiasi agente che non abbia, secondo il contratto e de facto, il potere di negoziare liberamente il prezzo dei contratti di vendita conclusi, per conto del venditore, con un acquirente (tale libertà di negoziazione si estende anche ad altri termini essenziali della vendita, come i termini di consegna o di pagamento).

La restrizione fissata dai tribunali francesi

Questo approccio è stato criticato perché, tra l’altro, risultava essere contrario alla natura stessa della funzione economica e giuridica dell’agente di commercio, che deve sviluppare l’attività del preponente nel rispetto della sua politica commerciale, in modo uniforme e nel rigoroso rispetto delle istruzioni impartite.

Poiché la maggior parte dei contratti di agenzia soggetti al diritto francese escludono espressamente la libertà dell’agente di negoziare i prezzi o le condizioni principali dei contratti di vendita, i giudici hanno regolarmente riqualificato il contratto da contratto di agenzia commerciale a contratto di mandato di interesse comune. Tuttavia, questo contratto di mandato d’interesse comune non è disciplinato dalle disposizioni degli articoli L 134 e seguenti del Codice di commercio, molti dei quali sono di ordine pubblico interno, ma dalle disposizioni del Codice civile relative al mandato, che in generale non sono considerate di ordine pubblico.

La principale conseguenza di questa dicotomia di status consiste nella possibilità per il preponente vincolato da un contratto di mandato di mettere espressamente da parte l’indennità di fine rapporto, essendo questa clausola perfettamente valida in un contratto di questo tipo, a differenza del contratto di agente di commercio (si veda il capitolo francese della Guida pratica ai contratti di agenzia commerciale internazionale).

La decisione della CGCE e gli effetti

La sentenza della CGCE del 4 giugno 2020 pone fine all’approccio restrittivo dei tribunali francesi. Secondo quest’ultima l’interpretazione corretta dell’articolo 1, paragrafo 2, della direttiva del 18 dicembre 1986 è che gli agenti non devono necessariamente avere il potere di modificare i prezzi dei beni che vendono per conto di un preponente per essere classificati come agenti di commercio.

La Corte ricorda in particolare che la direttiva europea è valida per qualsiasi agente che abbia il potere di negoziare o di negoziare e concludere contratti di vendita. La Corte aggiunge che il concetto di negoziazione non può essere letto attraverso la lente restrittiva adottata dai giudici francesi. La definizione del concetto di “negoziazione” deve non solo tenere conto del ruolo economico che ci si aspetta da tale intermediario (essendo il concetto di negoziazione molto ampio: ad es. la contrattazione), ma anche della necessità di preservare gli obiettivi della direttiva, soprattutto garantire la tutela di questo tipo di intermediario.

In pratica, quindi, i preponenti non potranno più nascondersi dietro una clausola che vieta all’agente di negoziare liberamente i prezzi e i termini dei contratti di vendita per negare lo status di agente di commercio.

Opzioni alternative per i preponenti

Quali sono i mezzi di cui dispongono ora i produttori e i commercianti francesi o stranieri per evitare di pagare un indennizzo al termine del contratto di agenzia?

- Innanzitutto, in caso di contratti internazionali, i preponenti stranieri avranno probabilmente più interesse a sottoporre il proprio contratto a una legge straniera (a condizione che non sia più restrittiva della legge francese …). Anche se le regole dell’agenzia di commercio non sono considerate delle norme imperative preminenti dai tribunali francesi (contrariamente ai casi Ingmar e Unamar della CGCE), per garantire la possibilità di escludere il diritto francese il contratto dovrebbe anche prevedere una clausola di giurisdizione esclusiva per un tribunale straniero o una clausola arbitrale (si veda il capitolo francese della Guida pratica ai contratti di agenzia commerciale internazionale).

- C’è anche la probabilità che il preponente chieda un compenso all’agente per il contributo della sua banca dati clienti (preesistente) e che il pagamento di tale compenso venga differito alla fine del contratto … al fine di compensare, se necessario, in tutto o in parte, il corrispettivo allora dovuto all’agente di commercio.

- È certo che i contratti di agenzia stabiliranno in modo più chiaro e completo i doveri dell’agente che il preponente considera essenziali e la cui violazione potrebbe costituire una grave mancanza, escludendo il diritto ad un compenso di fine contratto. Sebbene i giudici siano liberi di valutare la gravità della violazione, possono comunque utilizzare le disposizioni contrattuali per identificare ciò che è importante nell’intenzione comune delle parti.

- Alcuni preponenti metteranno probabilmente in dubbio anche l’opportunità di continuare ad utilizzare gli agenti di commercio, e in alcuni casi la loro attività potrebbe essere meno legata a una questione di contratto di agenzia commerciale, ma piuttosto a un contratto di servizi promozionali. La distinzione tra questi due contratti deve comunque essere rigorosamente osservata sia nel testo dell’accordo che nella realtà, e bisognerebbe valutare altre conseguenze, come il regime del preavviso (vedi il nostro articolo sulla risoluzione improvvisa dei contratti).

Infine, il ragionamento utilizzato dalla CGCE in questa sentenza (interpretazione autonoma alla luce del contesto e dello scopo di questa direttiva) potrebbe indurre i preponenti a mettere in discussione la norma della giurisprudenza francese che consiste nel concedere, a occhi quasi chiusi, due anni di commissioni lorde a titolo di indennizzo forfettario, mentre l’articolo 134-12 del Codice commerciale non fissa l’importo di questo indennizzo di fine contratto, ma si limita ad indicare che il danno effettivo subito dall’agente deve essere risarcito; così come l’articolo 17.3 della direttiva CE del 1986. Ci si potrebbe quindi chiedere se tale articolo 17.3 imponga all’agente di provare il danno effettivamente subito.

Summary: Since 12 July 2020, new rules apply for platform service providers and search engine operators – irrespective of whether they are established in the EU or not. The transition period has run out. This article provides checklists for platform service providers and search engine operators on how to adapt their services to the Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 on the promotion of fairness and transparency for commercial users of online intermediation services – the P2B Regulation.

The P2B Regulation applies to platform service providers and search engine operators, wherever established, provided only two conditions are met:

(i) the commercial users (for online intermediation services) or the users with a company website (for online search engines) are established in the EU; and

(ii) the users offer their goods/services to consumers located in the EU for at least part of the transaction.

Accordingly, there is a need for adaption for:

- Online intermediation services, e.g. online marketplaces, app stores, hotel and other travel booking portals, social media, and

- Online search engines.

The P2B Regulation applies to platforms in the P2B2C business in the following constellation (i.e. pure B2B platforms are exempt):

Provider -> Business -> Consumer

The article follows up on the introduction to the P2B Regulation here and the detailed analysis of mediation as method of dispute resolution here.

Checklist how to adapt the general terms and conditions of platform services

Online intermediation services must adapt their general terms and conditions – defined as (i) conditions / provisions that regulate the contractual relationship between the provider of online intermediation services and their business users and (ii) are unilaterally determined by the provider of online intermediation services.

The checklist shows the new main requirements to be observed in the general terms and conditions (“GTC”):

- Draft them in plain and intelligible language (Article 3.1 a)

- Make them easily available at any time (also before conclusion of contract) (Article 3.1 b)

- Inform on reasons for suspension / termination (Article 3.1 c)

- Inform on additional sales channels or partner programs (Article 3.1 d)

- Inform on the effects of the GTC on the IP rights of users (Article 3.1 e)

- Inform on (any!) changes to the GTC on a durable medium, user has the right of termination (Article 3.2)

- Inform on main parameters and relative importance in the ranking (incl. possible influence of remuneration), without algorithms or business secrets (Article 5.1, 5.3, 5.5)

- Inform on the type of any ancillary goods/services offered and any entitlement/condition that users offer their own goods/services (Article 6)

- Inform on possible differentiated treatment of goods / services of the provider or individual users towards other users (Article 7.1, 7.2, 7.3)

- No retroactive changes to the GTC (Article 8a)

- Inform on conditions under which users can terminate contract (Article 8b)

- Inform on available or non-available technical and contractual access to information that the Service maintains after contract termination (Article 8c)

- Inform on technical and contractual access or lack thereof for users to any data made available or generated by them or by consumers during the use of services (Article 9)

- Inform on reasons for possible restrictions on users to offer their goods/services elsewhere under other conditions (“best price clause”); reasons must also be made easily available to the public (Article 10)

- Inform on access to the internal complaint-handling system (Article 11.3)

- Indicate at least two mediators for any out-of-court settlement of disputes (Article 12)

These requirements – apart from the clear, understandable language of the GTC, their availability and the fundamental ineffectiveness of retroactive adjustments to the GTC – clearly go beyond what e.g. the already strict German law on general terms and conditions requires.

Checklist how to adapt the design of platform services and search engines

In addition, online intermediation services and online search engines must adapt their design and, among other things, introduce internal complaint-handling. The checklist shows the main design requirements for:

a) Online intermediation services

- Make identity of commercial user clearly visible (Article 3.5)

- State reasons for suspension / limitation / termination of services (Article 4.1, 4.2)

- Explain possible differentiated treatment of goods / services of providers themselves or users in relation to other users (Article 7.1, 7.2, 7.3), see above

- Set an internal complaint handling system, with publicly available info, annual updates (Article 11, 4.3)

b) Online search engines

- Explain the ranking’s main parameters and their relative importance, public, easily available, always up to date (incl. possible influence of remuneration), without algorithms or trade secrets (Article 5.2, 5.3, 5.5)

- If ranking changes or delistings occur due to notification by third parties: offer to inspect such notification (Article 5.4)

- Explain possible differentiated treatment of goods / services of providers themselves or users in relation to other users (Article 7.1, 7.2, 7.3)

The European Commission will provide guidelines regarding the ranking rules in Article 5, as announced in the P2B Regulation – see the overview here. At the same time, providers of online intermediation services and online search engines shall draw up codes of conduct together with their users.

Practical Tips

- The Regulation significantly affects contractual freedom as it obliges platform services to adapt their general terms and conditions.

- The Regulation is to be enforced by “representative organisations” or associations and public bodies, with the EU Member States ensuring adequate and effective enforcement. The European Commission will monitor the impact of the Regulation in practice and evaluate it for the first time on 13.01.2022 (and every three years thereafter).

- The P2B Regulation may affect distribution relationships, in particular platforms as distribution intermediaries. Under German distribution law, platforms and other Internet intermediation services acting as authorised distributors may be entitled to a goodwill indemnity at termination (details here) if they disclose their distribution channels on the basis of corresponding platform general terms and conditions, as the Regulation does not require, but at least allows to do (see also: Rohrßen, ZVertriebsR 2019, 341, 344–346). In addition, there are numerous overlaps with antitrust, competition and data protection law.

It is usually said that “conflict is not necessarily bad, abnormal, or dysfunctional; it is a fact of life[1]” I would perhaps add that quite often conflict is a suitable opportunity to evolve and to solve problems[2]. It is, in fact, a useful part of life[3] and particularly, should I add, of businesses. And conflicts not only arise at the end of the business relationship or to terminate it, but also during it and the parties remain willing to continue it.

The 2008 EU Directive on certain aspects of mediation in civil and commercial matters states that «agreements resulting from mediation are more likely to be complied with voluntarily and are more likely to preserve an amicable and sustainable relationship between the parties.»

Can, therefore, mediation be used not only as an alternative to court or arbitration when terminating distribution agreements, but also to re-organize them or to change contract conditions? Would it be useful to solve these conflicts? What could be the advantages?

In distribution/agency/franchise agreements, particularly for those lasting several years, parties can have neglected their obligations (for instance minimum sales targets not attained).

Sometimes they could have tolerated the situation although they remain not very happy with the other party’s performance because they are still doing acceptable business.

It could also happen that one of the parties wishes to restructure the entire distribution network (Can we change the distribution structure to an agency one?), but does not want to face a complete termination because there are other benefits in the relationship.

There may be just some changes to be introduced, or changes in the legal structures (A mere reseller transformed in distributor?), legal frameworks, legal conditions (Which one is the applicable law?), limitation of the scope of contract, territory…

And now, we face the Covid-19 crisis where everything is still more uncertain.

In some cases, it could happen that there is no written contract and the parties wish to draft it; in other cases, agreements could have been defectively drafted with incomplete, contradictory or no regulation at all (Was it an exclusive agreement?).

The contracts could be perfect for the situation imagined when signed several years ago but not anymore (What happen with online sales?) or circumstances, markets, services, products have changed and need to be reconsidered (mergers, change of directors…).

Sometimes, even more powerful parties have not the elements to oblige the weaker party to respect new terms, or they simply prefer not to impose their conditions, but to build up a more collaborative relationship for the future.

In all these cases, negotiation is the usual strategy parties follow: each one is focused in obtaining its own benefits with a clear idea of, for instance, which clause(s) should be modified or drafted.

Nevertheless, mediation could add some neutrality, and some space to a more efficient, structured and useful approach to the modification of the commercial relationship, particularly in distribution agreements where the collaboration (in the past, but also in the future if the parties wish so) is of paramount importance.

In most of these situations, personal emotional aspects could also be involved and make more difficult a neutral negotiation: a distributor that has been seen by the manufacturer as not performing very well and feels hurt, an agent that could consider a retirement, parties from different cultures that need to understand different ways of performing, franchisees that have been treated differently in the network and feel discriminated, etc.

In these circumstances and in other similar ones, where all persons involved, assisted by their respective lawyers, wish to continue the relationship although maybe in a different way, a sort of facilitative mediation can be a great help.

These are, in my opinion, the main reasons:

- Mediation is a legal and organized procedure that could help the parties to increase their awareness of the necessity to redraft the agreement (or drafting for the first time if it was not already done).

- Parties can be heard more easily, negotiation is eased in the interest of both of them, encourages them to act more reasonably vis-à-vis the other side, restores relationship if necessary, deadlock can be easily broken and, if the circumstances advice so, parties can be engaged separately with the help of the mediator.

- Mediation can consider other elements different to the mere commercial or legal ones: emotions linked to performance, personal situations (retirement, succession, illness) or even differences in cultural approaches.

- It helps to find the real (possibly new or not shown) interests in the commercial relationship of the parties, focusing in developments, strategies, new proposals… The mere negotiation between the parties and they attorneys could not make appear these new interests and therefore be limited only to the discussion on the change of concrete obligations, clauses or situations. Mediation helps to go beyond.

- Mediation techniques can also help the parties to face their current situation, to take responsibility of their performance without focusing on blame or incompetence but on a constructive and future collaboration in new specific terms.[4]

- It can also avoid the increasing of the conflict into a more severe one (breaching) and in case mediation does not end with a new/redrafted agreement, the basis for a mediated termination can be established, if the parties wish so, instead of litigation.

- Mediation can conclude into a new agreement where the parties are more reassured, more comfortable with, and more willing to respect because they were involved in their construction with the assistance of their respective lawyers, and because all their interests (not only new drafted clauses) were considered.

- And, in any case, mediation does not affect the party’s collaborative position and does not reduce their possibility to use other alternatives, including litigation or arbitration to terminate the agreement or to oblige the other party to respect its legal obligations.

The use of mediation does not need the parties to have foreseen it in the agreement (although it could be easier if they did so) but they can use it freely at any time.

This said, a lawyer proposing mediation as a contractual clause or, in case it was not included in the agreement, as a procedure to face this sort of conflicts in distribution agreements, will be certainly seen by his/her client as problem-solving attorney looking for the client’s interests rather than a litigator pushing them to a more uncertain situation, with unknown costs and unforeseeable timeframe.

Parties in distribution agreements should have this possibility in mind and lawyers have the opportunity to actively participate in mediation from the first steps by recommending it in the initial agreement, during the process helping the clients to express their concerns and interests, and in the drafting of the final (new) agreement, representing the clients’ and as co-author of their success.

If you would like to hear more on the topic of mediation and distribution agreements you can check out the recording of our webinar on Mediation in International Conflicts

[1] Moore, Christopher W. The Mediation Process: Practical Strategies for Resolving Conflict. Jossey-Bass. Wiley, 2014.

[2] Mnookin, Robert H. Beyond Winning. Negotiating to create value in deals and disputes (p. 53). Harvard University Press, 2000.

[3] Fisher, R; Ury, W. Getting to Yes: Negotiating an agreement without giving in. Random House.

[4] «Talking about blame distracts us from exploring why things went wrong and how we might correct them going forward. Focusing instead on understanding the contribution system allows us to learn about the real causes of the problem, and to work on correcting them.» [Stone, Douglas. “Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most”. Penguin Publishing Group]

Riassunto

Anche in Italia l’emergenza Covid-19 ha accelerato parecchio la transizione verso l’e-commerce, sia nei rapporti B2C che in molti settori B2B. Molte imprese si sono trovate ad operare su internet per la prima volta, spostando nel mondo digitale le relazioni commerciali e i rapporti con i clienti.

Purtroppo, accade spesso che dietro a manifestazioni di interesse di potenziali clienti si nascondano dei tentativi di truffa. E’ il caso, in particolare, di nuovi contatti commerciali provenienti dalla Cina, via email o tramite il sito web aziendale o i profili sui social network dell’azienda.

Vediamo quali sono gli schemi ricorrenti di truffe, piccole e grandi, che ricorrono frequentemente, soprattutto nel mondo del vino, nel settore alimentare e in quello della moda.

Di cosa parlo in questo post:

- La richiesta di prodotti via internet da un compratore cinese

- La legalizzazione del contratto in Cina, la firma dal notaio cinese e altre spese

- La modifica dei termini di pagamento (Man in the mail)

- La falsa registrazione del marchio o dominio web

- Designer e prodotti di moda: la fantomatica piattaforma e-commerce

- La truffa dei bitcoin e delle criptovalute

- Come verificare i dati di una società cinese

- Come possiamo aiutarti

Affare imperdibile, normale richiesta commerciale o tentativo di raggiro?

Fortunatamente i malintenzionati in Cina (e non solo: spesso questo tipo di truffe viene perpetrato anche da criminali di altri paesi) non sono molto creativi e gli schemi utilizzati per i “bidoni” sono ben noti e ricorrenti: vediamo i principali.

L’invito a firmare il contratto in Cina

Il caso più frequente è quello di una società cinese che, dopo aver reperito informazioni sui prodotti italiani attraverso il sito web dell’azienda italiana, comunica via email la disponibilità ad acquistare importanti quantitativi di merce.

Segue di solito un primo scambio corrispondenza via email tra le parti, all’esito del quale la società cinese comunica la decisione di acquistare i prodotti e chiede di finalizzare l’accordo in tempi molto rapidi, invitando la parte italiana a recarsi in Cina per concludere la trattativa e non lasciar sfumare l’affare.

Molti ci credono e non resistono alla tentazione di saltare sul primo aereo: sbarcati in Cina la situazione sembra ancor più allettante, visto che il potenziale compratore si dimostra un negoziatore molto arrendevole, disponibile ad accettare tutte le condizioni proposte dalla parte italiana e frettoloso di concludere il contratto.

Questo però non è un buon segno, anzi: deve suonare come un campanello d’allarme. E’ noto che i cinesi sono negoziatori abili e molto pazienti e le trattative commerciali di solito sono lunghe e snervanti: una trattativa troppo semplice, soprattutto se si tratta del primo incontro tra le parti, è molto sospetta.

Che ci si trovi di fronte ad un tentativo di truffa è certificato poi dalla richiesta di alcuni pagamenti in Cina al fine di poter concludere l’affare.

Esistono diverse varianti di questo primo schema.

Le più comuni sono la richiesta di pagare una tassa di registrazione del contratto presso un notaio cinese; un contributo spese per incombenti amministrativi o doganali; un pagamento in contanti per ammorbidire le autorità preposte ed ottenere in tempi rapidi licenze o permessi di importazione dei beni, l’offerta di pranzi o cene a potenziali partner commerciali (a prezzi gonfiati), il soggiorno in un albergo prenotato dalla parte cinese, salvo poi ricevere la sorpresa di un conto esorbitante.

Rientrato in Italia, purtroppo, molto spesso il contratto firmato resterà un inutile pezzo di carta, il fantomatico cliente si renderà irreperibile e la società cinese risulterà inesistente. Si avrà allora la certezza che l’intera operazione era architettata al solo fine di estorcere all’incauto straniero qualche migliaio di euro.

Lo stesso schema (ossia l’ordine commerciale seguito da una serie di richieste di pagamento) può anche essere effettuato online, con motivazioni simili a quelle indicate: gli indizi della truffa sono sempre il contatto da parte di uno sconosciuto per un ordine di valore molto elevato, un negoziato molto rapido con richiesta di concludere l’affare in tempi stretti e la necessità di procedere a qualche pagamento anticipato prima di concludere il contratto.

Il pagamento su un diverso conto corrente

Un’altra truffa molto frequente è quella del conto corrente bancario diverso da quello solitamente utilizzato.

Qui le parti di solito sono invertite. La società cinese è il venditore dei prodotti, da cui l’imprenditore italiano intende acquistare o ha già acquistato una serie di partite di merce.

Un giorno il venditore o l’agente di riferimento informa il compratore che il conto corrente bancario normalmente utilizzato è stato bloccato (le scuse più frequenti sono che stato ecceduto il limite di valuta estera autorizzato, o sono in corso verifiche amministrative, o semplicemente si è cambiata la banca utilizzata), con invito a provvedere al pagamento del prezzo su un diverso conto corrente, intestato ad altro soggetto.

In altri casi la richiesta è motivata dal fatto che la fornitura dei prodotti avviene per il tramite di un’altra società, che è titolare della licenza di esportazione dei prodotti ed è autorizzata a ricevere il pagamento per conto del venditore.

Dopo avere eseguito il pagamento, il compratore italiano riceve l’amara sorpresa: il venditore dichiara non ha mai ricevuto il pagamento, che il diverso conto corrente non appartiene alla società e che la richiesta di pagamento su altro conto proveniva da un hacker che ha intercettato la corrispondenza tra le parti.

Solo a quel punto, verificando l’indirizzo email dal quale è stata trasmessa la richiesta di utilizzo del nuovo conto corrente, il compratore si avvede in genere di qualche piccola differenza nell’account email utilizzato per la richiesta di pagamento sul diverso conto (es. diverso nome a dominio, diverso provider o differente nome utente).

Il venditore a quel punto si renderà disponibile a spedire la merce solo a condizione che il pagamento venga rinnovato sul conto corrente corretto, cosa che – evidentemente – è bene non fare per non essere ingannati una seconda volta. Le ricerche di verifica dell’intestatario del falso conto corrente in genere non portano ad alcuna risposta da parte della banca e sarà di fatto impossibile identificare gli autori della truffa.

La truffa della falsa registrazione del marchio o del dominio web in Cina

Un altro classico schema cinese è l’invio di un’email con la quale si informa di aver ricevuto una richiesta da parte di un soggetto cinese, intenzionato a registrare un marchio o un dominio web identico a quello della società destinataria della comunicazione.

A scrivere è una sedicente agenzia cinese del settore, che comunica la propria disponibilità ad intervenire e sventare il pericolo, bloccando la registrazione, a condizione che si provveda in tempi rapidissimi e si paghi anticipatamente il servizio.

Anche in questo caso siamo di fronte ad un maldestro tentativo di truffa: meglio cestinare subito l’email.

A proposito: se non avete registrato il vostro marchio in Cina, fatelo subito. Ci fosse interessato ad approfondire l’argomento può farlo qui.

Designer e prodotti di moda: la fantomatica piattaforma di e-commerce

Una truffa molto diffusa è quella che riguarda designer e aziende del settore moda: anche in questo caso il contatto arriva tramite il sito web o l’account social media dell’azienda ed esprime un grande interesse per importare e distribuire in Cina prodotti del designer o del brand italiano.

Nei casi che di cui mi sono occupato in passato la proposta è accompagnata da un corposo contratto di distribuzione in inglese, che prevede la concessione in esclusiva del marchio e del diritto di vendere i prodotti in Cina a favore di una fantomatica piattaforma online cinese, in corso di costruzione, che consentirà di raggiungere un elevatissimo numero di clienti.

Dopo avere firmato il contratto i pretesti per estorcere denaro all’azienda italiana sono simili a quelli visti in precedenza: invito in Cina e richiesta di una serie di pagamenti in loco, oppure necessità di coprire una serie di costi di cui si deve far carico la parte cinese per avviare le operazioni commerciali in Cina: registrazione del brand, adempimenti doganali, ottenimento di licenze, etc (ovviamente tutti inventati).

La truffa dei bitcoin e delle criptovalute

Di recente uno schema di truffa di provenienza cinese è quello della proposta di investire in bitcoin, con garanzia di un ritorno minimo garantito sull’investimento molto allettante (in genere 20 o 30%).

Il presunto trader si presenta in questi casi come rappresentante di un’agenzia con sede in Cina, spesso facendo riferimento ad un sito web costruito ad hoc e a presentazioni dei servizi di investimento realizzate in inglese.

Nello schema si coinvolge solitamente anche una banca internazionale, che funge da agente o depositaria delle somme: in realtà chi scrive è sempre l’organizzazione criminale, da un account fasullo che assomiglia a quello della banca o dell’intermediario finanziario.

Una volta pagate le somme il broker scompare e non è possibile rintracciare i fondi perché il conto corrente bancario viene chiuso e la società scompare, o perché i pagamenti sono stati fatti tramite bitcoin.

Gli indizi della truffa anche in questo caso sono simili a quelli visti in precedenza: contatto proveniente da internet o via email, proposta commerciale molto allettante, fretta di concludere l’accordo.

Come capire se abbiamo a che fare con una truffa via internet

Nei casi visti sopra, ed in altri simili, una volta perpetrata la truffa è pressoché inutile cercare di porvi rimedio: i costi e le spese legali sono di solito superiori al valore del danno e nella maggioranza dei casi è impossibile rintracciare il responsabile del raggiro.

Ecco allora qualche consiglio utile – oltre al buon senso – per evitare di cadere in tranelli simili a quelli descritti:

Come verificare i dati di una società cinese

La denominazione della società in caratteri latini e il sito web in inglese non hanno alcuna valenza ufficiale, sono semplici traduzioni di fantasia: l’unico modo di verificare i dati della società cinese e delle persone che la rappresentano (o dicono di farlo) è quello di verificare la business licence originale e accedere al data base del SAIC (State Administration for Industry and Commerce).

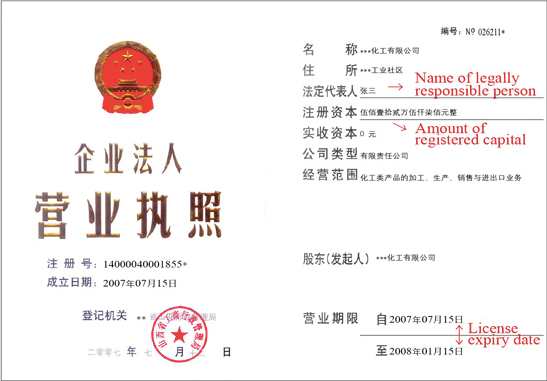

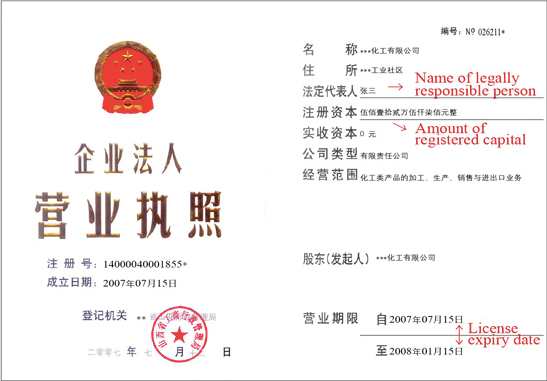

Ogni società cinese ha infatti una business license (equivalente alla visura CCIAA italiana) rilasciata dalla SAIC (che contiene le seguenti informazioni:

- nome ufficiale della società in caratteri cinesi;

- numero di registrazione;

- sede;

- oggetto sociale;

- data di costituzione e scadenza;

- legale rappresentante;

- capitale registrato e versato.

Si tratta di un documento in lingua cinese, simile al seguente:

Verificare le informazioni, con l’aiuto di un professionista competente, consentirà di appurare se la società esiste o meno, l’identità dell’interlocutore, l’affidabilità della società e il fatto che il sedicente rappresentante possa in effetti spendere il nome della società.

Chiedere referenze commerciali

A prescindere che l’interesse sia per importare vino italiano, per il settore della moda o del design o altro prodotto Made in Italy, una verifica semplice da fare è quella di chiedere con che altre società italiane o internazionali il nostro interlocutore ha lavorato in precedenza, per validare le informazioni ricevute.

Nella maggior parte dei casi la parte cinese opporrà di non poter dare referenze per motivi di privacy, il che conferma il sospetto che in realtà tali fantomatici casi di successo non esistano e si tratti di un tentativo di truffa.

Gestire con attenzione i pagamenti

Smarcati positivamente i primi punti, è bene procedere comunque con molta prudenza, specie nel caso di nuovo cliente o fornitore. Nel caso di vendita di prodotti ad un compratore cinese è opportuno chiedere un pagamento in acconto anticipato e il saldo del prezzo all’avviso di merce pronta, oppure l’apertura di una lettera di credito.

Nel caso in cui la parte cinese sia il fornitore è raccomandato prevedere un’ispezione on site della merce, con incarico a società terza di certificare la qualità dei prodotti e la rispondenza alle specifiche contrattuali.

Verificare le richieste di cambiamento delle modalità di pagamento

Se una relazione commerciale è già in corso e viene chiesto di cambiare la modalità di pagamento del prezzo, va verificata con attenzione l’identità e l’account email del richiedente e per sicurezza è bene chiedere conferma dell’istruzione anche attraverso altri canali di comunicazione (scrivendo ad altra persona in azienda, telefonando o mandando un messaggio via wechat).

Come possiamo aiutarti

Legalmondo offre la possibilità di lavorare con un avvocato specializzato per esaminare la tua esigenza o assisterti nella redazione di un contratto o nei negoziati contrattuali con la Cina.

Accedi al nostro servizio di Contrattualistica Internazionale

Photo by Andy Beales on Unsplash.

Riassunto: In Germania, al termine di un contratto di distribuzione, gli intermediari di una rete di distribuzione (in particolare, i distributori/franchisee) possono chiedere un’indennità al proprio produttore/fornitore, se si configura una fattispecie analoga a quella dell’agente commerciale. Tali condizioni sussistono se l’intermediario è integrato nella rete commerciale del fornitore ed è obbligato a trasferire il proprio portafoglio clienti al fornitore, cioè a trasmettere i dati dei propri clienti in modo che il fornitore possa immediatamente e senza ulteriori indugi sfruttare i vantaggi del portafoglio clienti al termine del contratto. Una recente decisione giudiziaria mira ora ad estendere il diritto all’indennità del distributore a casi in cui il fornitore abbia in qualche modo beneficiato del rapporto commerciale con il distributore, anche nel caso in cui il distributore non abbia fornito i dati dei clienti al fornitore. Questo articolo illustra tale novità e fornisce suggerimenti su come superare le incertezze emerse a seguito di questa nuova decisione.

Un tribunale tedesco ha recentemente ampliato il diritto del distributore all’indennità di fine rapporto: i fornitori potrebbero dover pagare l’indennità ai propri distributori autorizzati anche nel caso in cui questi ultimi non fossero obbligati a trasferire la propria clientela al fornitore. Al contrario, potrebbe essere sufficiente il conseguimento di un qualsiasi avviamento – inteso come vantaggi sostanziali che, a seguito della cessazione del rapporto, il fornitore possa derivare dalla relazione commerciale con il distributore, indipendentemente da che cosa le parti abbiano stipulato nell’accordo di distribuzione.

Questa decisione potrebbe influire su tutti i tipi di business in cui i prodotti siano venduti tramite distributori (e franchisee, vedi sotto) – in particolare, quindi, sul commercio al dettaglio (soprattutto per quanto riguarda prodotti di elettronica, cosmetica, gioielleria e talvolta anche moda), sul settore automobilistico e sul commercio all’ingrosso. I distributori sono imprenditori autonomi e indipendenti i quali vendono e promuovono i prodotti

- stabilmente ed in nome proprio (differentemente dagli agenti commerciali),

- per proprio conto (differentemente dagli agenti commissionari),

- perciò sopportando il rischio ed i cui margini di profitto – per contro – sono piuttosto alti.

Nel diritto tedesco i distributori sono meno protetti rispetto agli agenti commerciali. Tuttavia, anche i distributori e gli agenti commissionari (vedi qui) hanno diritto ad ottenere un’indennità alla cessazione del contratto, qualora sussistano due prerequisiti:

- il distributore o agente commissionario sia integrato nella rete di vendita del concedente/fornitore (più di un semplice rivenditore) e

- sia obbligato (contrattualmente o di fatto) ad inoltrare al fornitore i dati della clientela durante o al termine dell’esecuzione del contratto (Corte Federale tedesca, decisione del 26 novembre 1997, R.G. n. VIII ZR 283/96).

Ora, il Tribunale Regionale di Norimberga-Fürth ha stabilito che il secondo prerequisito sussiste già se il distributore ha procurato un avviamento al concedente:

“… l’unico fattore decisivo, ai fini di un’applicazione analogica, è se il convenuto (il concedente) ha tratto beneficio dalla relazione commerciale con l’attore (distributore). …

… il concedente deve corrispondere un’indennità se ha un “avviamento”, ossia una giustificata aspettativa di profitto dalle relazioni commerciali con la clientela procurata dal distributore.”

(cfr. decisione del 27 novembre 2018, R.G. n. 2 HK O 10103/12).

Al fine di giustificare tale estensiva applicazione, il tribunale ha fatto riferimento in via astratta alle conclusioni dell’avvocato generale della Corte UE nel caso Marchon/Karaszkiewicz, rese il 10 settembre 2015. Tale caso, tuttavia, non concerneva distributori, bensì il diritto all’indennità dell’agente commerciale, in particolare il concetto di “nuovi clienti” ai sensi della Direttiva 86/653/EEC sugli agenti commerciali.

Nel presente caso, secondo il tribunale, è sufficiente che il fornitore abbia sul proprio computer i dati sui clienti procurati dal distributore e possa fare liberamente uso degli stessi. Altre ipotesi in cui potrebbe sorgere il diritto del distributore all’indennità, persino a prescindere dai dati concreti sulla clientela, sarebbero casi in cui il fornitore rilevi il negozio dal distributore e i clienti conseguentemente continuino a visitare proprio quel negozio anche dopo che il distributore lo ha lasciato.

Consigli pratici:

1. La decisione rende l’inquadramento giuridico dei distributori / franchisee meno chiaro. L’interpretazione estensiva del tribunale, tuttavia, deve essere vista alla luce della giurisprudenza della Corte Federale: ancora nel 2015, la Corte ha negato il diritto all’indennità ad un distributore, contestando la mancanza del secondo requisito, in quanto il distributore non era obbligato a trasferire i dati sulla clientela (decisione del 5 febbraio 2015, R.G. n. VII ZR 315/13, facendo seguito alla propria precedente decisione nel caso Toyota del 17 aprile 1996, R.G. n. VIII ZR 5/95). Inoltre, la Corte Federale ha negato ai franchisee il diritto all’indennità qualora il franchising abbia ad oggetto un business anonimo di massa e la clientela continui ad essere clientela regolare soltanto in via di fatto (decisione del 5 febbraio 2015, R.G. n. VII ZR 109/13 nel caso della catena di panetterie “Kamps”). Resta da vedere come si evolverà questa giurisprudenza.

2. In ogni caso, prima di entrare nel mercato tedesco, i fornitori devono valutare se intendano assumersi il rischio di dover pagare un’indennità alla cessazione del contratto.

3. Lo stesso vale per i franchisor: i franchisee saranno probabilmente in grado di far valere il diritto ad un’indennità sulla base dell’applicazione analogica della normativa sull’agenzia commerciale. Fino ad ora, la Corte Federale ha negato il diritto all’indennità del franchisee caso per caso, lasciando così aperta la questione se i franchisee possano in via generale far valere un tale diritto (cfr. ad esempio la decisione del 23 luglio 1997, R.G. n. VIII ZR 134/96 nella causa sui negozi Benetton). Nondimeno, i tribunali tedeschi potrebbero probabilmente riconoscere il diritto all’indennità nel caso del franchising distributivo (in cui il franchisee compra i prodotti dal franchisor), qualora la situazione sia simile alla distribuzione e all’agenzia commerciale. Questo potrebbe essere il caso in cui il franchisee sia stato incaricato di distribuire i prodotti del franchisor e solo il franchisor abbia, al termine del contratto, diritto ad accedere ai nuovi clienti acquisiti dal franchisee durante il contratto (cfr. Corte Federale tedesca, decisione del 29 aprile 2010, R.G. n. I ZR 3/09, Joop). Nessun diritto all’indennità, tuttavia, può essere fatto valere se

- il franchise ha ad oggetto un business anonimo di massa e i clienti continuano ad essere regolari soltanto di fatto (decisione del 5 febbraio 2015, nella causa sulla catena di panetterie “Kamps”) o

- nei franchising di produzione (contratti di imbottigliamento, ecc.), in cui il franchisor o titolare della licenza non opera nello stesso identico settore dei prodotti distribuiti dal franchisee / licenziatario (decisione del 29 aprile 2010, R.G. n. I ZR 3/09, Joop).

4. Nel diritto tedesco, il diritto all’indennità dei distributori – o, potenzialmente, dei franchisee – può ancora essere escluso:

- scegliendo di applicare al contratto un altro diritto sostanziale che non preveda un’indennità;

- obbligando il fornitore a bloccare, non usare e, se necessario, cancellare i dati della clientela alla cessazione del contratto (Corte Federale tedesca, decisione del 5 febbraio 2015, R.G. n. VII ZR 315/13: “fatte salve le disposizioni riportate all’articolo [●] sotto, il fornitore deve bloccare i dati forniti dal distributore dopo che sarà terminata la partecipazione del distributore al servizio clienti, deve cessare di utilizzarli e, su richiesta del distributore, deve cancellarli.”). Sebbene tale disposizione contrattuale sembri essere diventata irrilevante alla luce della decisione del Tribunale di Norimberga sopraccitata, il Tribunale non ha fornito alcun argomento sul perché la consolidata giurisprudenza della Corte Federale non debba trovare più applicazione;

- pattuendo espressamente l’esclusione del diritto all’indennità, il che, tuttavia, potrebbe funzionare solo qualora (i) il distributore operi al di fuori dello SEE e (ii) non sussista una norma locale inderogabile che preveda tale indennità (si veda l’articolo qui).

5. Inoltre, se il fornitore accetta deliberatamente di pagare l’indennità in cambio di un solido portafoglio clienti con una quantità di dati potenzialmente utilizzabili in modo significativo (in conformità con il Regolamento UE sulla Protezione Generale dei dati), può pattuire con il distributore il pagamento di “quote d’ingresso” (“entry fees”), al fine di mitigare il peso della propria obbligazione. Il pagamento di tali quote d’ingresso o oneri contrattuali potrebbe essere posticipato fino alla cessazione del contratto e successivamente compensato con il diritto all’indennità del distributore.

6. L’indennità di fine rapporto del distributore viene calcolata sulla base del margine di guadagno conseguito con nuovi clienti apportati dal distributore o con clienti già esistenti con cui il distributore abbia sensibilmente sviluppato gli affari. Il calcolo esatto può essere estremamente complesso ed i tribunali tedeschi applicano differenti metodi. In totale, l’indennità non può superare la media dei margini annualmente conseguiti dall’agente con tali clienti negli ultimi anni.

Scrivi a Christophe

P2B Regulation – How to adapt Platform services and Search Engines

2 Agosto 2020

-

Europa

- Mediazione

- Distribuzione

- eCommerce

Sotto la presidenza vietnamita dell’Associazione delle nazioni del Sud-est asiatico (ASEAN), dopo otto anni di negoziati i dieci Stati membri dell’ASEAN (Brunei, Cambogia, Filippine, Indonesia, Laos, Malesia, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailandia, Vietnam) il 15 novembre 2020 hanno firmato un clamoroso accordo di libero scambio (FTA) con Cina, Corea del Sud, Giappone, Australia e Nuova Zelanda, denominato Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

La comunità economica dell’ASEAN è un’area di libero scambio avviata nel 2015 tra i suddetti dieci membri dell’omonima associazione, che comprende un PIL aggregato di 2,6 trilioni di dollari e oltre 622 milioni di persone. L’ASEAN è il principale partner commerciale della Cina, con l’Unione Europea scivolata al secondo posto.

A differenza dell’Eurozona e dell’Unione Europea, l’ASEAN non ha una moneta unica, né istituzioni comuni, come la Commissione Europea, il Parlamento e il Consiglio. Analogamente a quanto accade nell’UE, tuttavia, un singolo membro detiene una presidenza a rotazione.

Singoli Paesi ASEAN, come Vietnam e Singapore, hanno recentemente stipulato accordi di libero scambio con l’Unione Europea, mentre l’intero blocco ASEAN aveva e ha tuttora in essere i cosiddetti accordi “più uno” con altri Paesi dell’area, ovvero la Repubblica Popolare Cinese, Hong Kong, la Repubblica di Corea,, il Giappone, l’India e l’Australia e la Nuova Zelanda insieme.

Ad eccezione dell’India, tutti gli altri Paesi con accordi “più uno” con l’ASEAN fanno ora parte dell’RCEP, che supererà progressivamente i singoli FTA attraverso l’armonizzazione delle regole, soprattutto quelle relative all’origine dei prodotti.

I negoziati RCEP sono accelerati con la decisione degli Stati Uniti d’America di ritirarsi dal Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement (TPP) con l’elezione del presidente Trump nel 2016 (anche se vale la pena di ricordare che anche gran parte del partito democratico degli Stati Uniti si era ai tempi opposta al TPP). Il TPP sarebbe stato quindi il più grande accordo di libero scambio di sempre e, come suggerisce il nome, avrebbe messo insieme dodici nazioni affacciate sull’Oceano Pacifico, ossia Australia, Brunei, Canada, Cile, Giappone, Malesia, Messico, Nuova Zelanda, Perù, Singapore, Vietnam e appunto Stati Uniti. Con l’esclusione di questi ultimi, gli altri undici hanno comunque firmato un accordo simile, denominato Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Il CPTPP è stato tuttavia ratificato solo da sette dei suoi firmatari e chiaramente non ne fa parte la più grande economia e partner più significativo di tutti. Allo stesso tempo, sia l’abortito TPP, sia il CPTPP escludono enfaticamente la Cina.

Il peso del RCEP è quindi evidentemente maggiore, in quanto nei Paesi firmatari, che rappresentano circa il 30% del PIL mondiale, vivono 2,1 miliardi di persone. E la porta per l’India con i suoi 1,4 miliardi di persone e 2,6 trilioni di dollari di PIL rimane aperta, hanno affermato gli altri membri.

Come la maggior parte degli accordi di libero scambio, l’obiettivo dell’RCEP è abbassare le tariffe, facilitare gli scambi di beni e servizi e promuovere gli investimenti. L’accordo affronta brevemente la tutela dei diritti di proprietà intellettuale, ma non fa menzione della tutela dell’ambiente e dei diritti dei lavoratori. I suoi firmatari comprendono economie molto avanzate, come quella di Singapore, e piuttosto povere, come quella della Cambogia.

Il significato dell’RCEP in questo momento è probabilmente più simbolico che tangibile. Anche se si stima che circa il 90% delle tariffe sarà abolito, ciò avverrà solo in un periodo di venti anni dall’entrata in vigore, cosa che accadrà solo dopo la ratifica. Inoltre, il settore dei servizi e soprattutto quello agricolo non rappresentano il fulcro dell’accordo e pertanto saranno ancora soggetti a barriere, regole e restrizioni nazionali. Ciononostante, si stima che, anche in questi tempi di pandemia, l’RCEP contribuirà annualmente al PIL mondiale per circa 40 miliardi di dollari in più rispetto al CPTPP (186 miliardi di dollari contro 147 miliardi di dollari) per dieci anni consecutivi.

Il suo impatto immediato è geopolitico. Sebbene i firmatari non siano affatto alleati di ferro (si pensi alle controversie territoriali sul Mar Cinese Meridionale, per esempio), il messaggio è chiaro:

- La maggior parte di questa parte del mondo ha affrontato la pandemia di Covid-19 molto bene, ma non può permettersi di aprire le sue frontiere a europei e americani in tempi brevi, per timore che il virus si diffonda di nuovo. Deve quindi cercare di appianare le tensioni interne, se vuole vedere nelle sue economie alcuni segnali positivi dati dal commercio privato, oltre alla spesa pubblica in deficit (non sempre “buona”). La maggior parte di questi Paesi fa molto affidamento sui talenti, sui turisti, sui beni, sui servizi e persino sul supporto strategico e militare dell’Occidente, ma è realista sul fatto che, a meno che il tanto pubblicizzato vaccino non funzioni molto bene e molto presto, l’Occidente lotterà con questo coronavirus per lunghi mesi, se non anni.