-

Germania

Commercial Agents outside the EEA – No Goodwill Indemnity (Ingmar reloaded)

29 Agosto 2017

- Distribuzione

- eCommerce

I produttori di articoli di marca tipicamente puntano ad assicurare lo stesso livello di qualità lungo tutti i canali di distribuzione. Al fine di conseguire tale scopo, essi stabiliscono criteri su come rivendere i propri prodotti. Con l’aumento delle vendite via internet, l’utilizzo di tali criteri è aumentato altrettanto.

Il miglior esempio: Asics. Fino al 2010, la controllata tedesca Asics Deutschland GmbH riforniva i propri distributori in Germania senza applicare criteri particolari. Nel 2011, Asics ha lanciato un sistema di distribuzione selettivo chiamato “Distribution System 1.0“. Esso prevede, tra le altre cose, un divieto generale, per i distributori, di usare strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi nelle vendite online:

“In aggiunta, il distributore autorizzato … non è da ritenersi autorizzato … a supportare la funzionalità di comparazione dei prezzi apportando l’interfaccia specifica d’applicazione (“API”) per tali strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi.” [tradotto]

L’Ufficio federale dei cartelli tedesco (“Bundeskartellamt”) ha stabilito, con decisione del 26 agosto 2015, che il divieto di utilizzare strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi nei confronti di distributori presenti in Germania era nullo in quanto viola l’articolo 101 (1) TFUE e l’art. 1 della Legge contro le limitazioni della concorrenza (cfr. il testo della decisione, di 196 pagine, qui). Il motivo addotto è che tale divieto punterebbe principalmente a controllare e limitare la competizione dei prezzi a spese del consumatore. Asics, per contro, ha presentato ricorso dinnanzi all’Alta Corte Regionale di Düsseldorf, al fine di vedere annullata la decisione dell’Ufficio federale dei cartelli, sostenendo che tale divieto era uno standard di qualità proporzionato nell’ambito del suo “Distribution System 1.0“, mirante a una presentazione uniforme dei prodotti.

Il 5 aprile 2017, l’Alta Corte Regionale di Düsseldorf ha confermato, così come la decisione dell’Ufficio federale dei cartelli, che nell’ambito di sistemi di distribuzione selettiva il divieto generale di usare strumenti comparazione dei prezzi era anticoncorrenziale e con ciò nullo (fasc. n. VI-Kart 13/15 (V); vedi altresì la rassegna stampa dell’Ufficio federale dei cartelli in inglese):

- In particolare, il divieto di strumentazione di comparazione dei prezzi non era dispensato, nell’ambito di una interpretazione teleologica (“Tatbestandsreduktion”), dall’art. 101 co. 1 TFEU. Secondo la Corte, ciò non era necessario al fine di proteggere la qualità e l’immagine di prodotto del brand Asics (ossia la stessa argomentazione dell’Alta Corte regionale di Francoforte nella sua sentenza del 22.12.2015, fasc. n. 11 U 84/14 riguardante gli zaini di Deuter; la Corte suprema federale non dovrà più decidere su tale caso perché la revisione è stata ritirata in marzo 2017, fasc. n. KZR 3/16). La Corte ha dichiarato che il divieto era volto a limitare i compratori, argomentando che i distributori sarebbero stati limitati nell’entrare in una competizione sui prezzi con altri. La presentazione di prodotti all’interno degli strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi non avrebbe danneggiato la qualità o il brand di prodotti Asics. Non avrebbe nemmeno dato “l’impressione di un mercato delle pulci”, nemmeno attraverso la presentazione, in parallelo, di prodotti usati. Inoltre, il divieto di strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi non risolverebbe comunque il problema del “free-riding”. In ogni caso, il divieto generale posto all’utilizzo di strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi non era necessario e perciò illegittimo.

- Il divieto, inoltre, non doveva ritenersi esentato dal regolamento sulle categorie di accordi verticali e pratiche concordate. Al contrario, la Corte ha rilevato che il divieto avrebbe limitato vendite passive (svolte cioè attraverso internet) verso consumatori finali, contrariamente all’art. 4 (c) del regolamento sulle categorie di accordi verticali e pratiche concordate (facendo riferimento alla decisione della Corte di Giustizia dell’UE nel caso di Pierre Fabre, 13 ottobre 2011, fasc. n. C-439/09). Il “principio di equivalenza” (secondo cui le restrizioni valide per le vendite offline così come online non dovrebbero essere identiche, ma funzionalmente equivalenti) non si applicherebbe, in quanto nel commercio tradizionale non ci sarebbero funzioni comparabili agli strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi.

- Infine, il divieto non beneficerebbe nemmeno dell’esenzione individuale di cui all’art. 101 co. 3 TFUE (“difesa dell’efficienza”).

Conclusioni

Secondo l’Alta Corte regionale di Düsseldorf, i produttori non potrebbero proibire generalmente ai loro distributori di usare strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi. Allo stesso tempo, la corte ha rifiutato di concedere l’autorizzazione a un appello contro la propria decisione – che, comunque, può essere richiesto separatamente, tramite la via dell’impugnazione (cfr. artt. 74, 75 della Legge contro le restrizioni in materia di concorrenza). Il futuro sviluppo di criteri limitanti i distributori nella rivendita online resta aperto, in particolare in quanto (i) il caso Coty è attualmente pendente presso la Corte di Giustizia dell’UE (vedi sotto) e (ii) la Commissione UE nella sua inchiesta di settore sull’e-commerce apparentemente sembra favorire i produttori di articoli di marca (vedi sotto).

- La Corte ha lasciato esplicitamente aperte – adducendo che non fossero rilevanti per la sua decisione – la questioni se:

- il divieto di motori di ricerca sia anti competitivo (paragrafo 44 e ss. della decisione);

- il divieto generale di usare piattaforme di terze parti sia anti competitivo (paragrafo 7) – sebbene il “Distribution System 1.0” di Asics vietasse anche piattaforme come Amazon e eBay.

- Se e come produttori di prodotti di lusso o di marca possono continuare a vietare la loro distribuzione via Amazon, eBay e altri mercati in generale verrà probabilmente deciso dalla Corte di Giustizia UE nei prossimi mesi – nel caso Coty (vedi il nostro post “eCommerce: restrizioni su distributori in Germania”) per il quale un’udienza ha già avuto luogo alla fine di marzo 2017.

- Senza pregiudizio per il caso Coty, la Commissione UE, nella propria inchiesta di settore sull’e-commerce del maggio 2017, dichiarato che

- “divieti di marketplaces in generale non producono una proibizione di fatto della vendita online, non restringono l’uso effettivo di internet come canale di vendita indipendentemente dai mercati colpiti dal divieto…”;

- “la potenziale giustificazione ed efficienze riportate dai produttori differiscono da un prodotto all’altro …”;

- “(assoluti) divieti di marketplaces non dovrebbero essere considerati quali restrizioni fondamentali nel significato dell’articolo 4(b) e articolo 4(c) del regolamento su categorie di accordi verticali e pratiche concordate …”;

- “la Commissione o una autorità nazionale della concorrenza potrebbe decidere di ritirare la protezione del regolamento su categorie di accordi verticali e pratiche concordate in casi particolari, se giustificato dalla situazione di mercato”

(41–43 del Report finale sull’inchiesta di settore sull’e-commerce).

- Per dettagli sulla distribuzione online e il diritto antitrust, si prega di consultare il mio ultimo articolo “Internetvertrieb in der EU 2018 ff. – Online-Vertriebsvorgaben von Asics über BMW bis Coty”, in: Zeitschrift für Vertriebsrecht 2017, pp. 274-281.

Perciò, sulla base della più recente posizione della Commissione Europea, vi è spazio per argomenti e per la redazione creativa di contratti, posto che anche divieti generali di mercato possono essere compatibili con le norme UE sulla concorrenza. Comunque, le corti potrebbero considerare la questione in modo differente nel singolo caso. Conseguentemente, soprattutto la Corte di Giustizia UE con il suo caso Coty (vedi sopra) porterà maggiore chiarezza per la futura distribuzione online. Sul caso Coty, la Corte di Giustizia UE deciderà il 6 dicembre 2017 (vedi il calendario giudiziario della Corte) : rimanete aggiornati sugli sviluppi seguendo il nostro blog.

The Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) has issued a new ruling on the international scope of the Commercial Agency Directive (86/653/EEC of 18 December 1986). The new decision is in line with the rulings of

- the CJEU in the Ingmar case (decision of 9 November 2000, C-381/98, goodwill indemnity mandatory where the agent acts within the EU) and Unamar (decision of 17 October 2013, C-184/12, as to whether national agency law is mandatory where exceeding the Commercial Agency Directive’s minimum protection) and

- the German Federal Supreme Court of 5 September 2012 (German agency law as mandatory law vis-à-vis suppliers in third countries with choice-of-court clause).

The question

Now, the CJEU had to decide whether a commercial agent acting in Turkey for a supplier based in Belgium could claim goodwill indemnity on the basis of the Commercial Agency Directive. More specifically, the question was whether the territorial scope of the Commercial Agency Directive was given where the commercial agent acts in a third country and the supplier within the EU – hence opposite to the Ingmar case.

The facts

According to the agency contract, Belgian law applied and the courts in Gent (Belgium) should be competent. Belgian law, transposing the Commercial Agency Directive, provides for a goodwill indemnity claim at termination of the contract (and, additionally, compensation for damages). However, the referring court considered that the Belgian Law on Commercial Agents of 1995 was self-restraining and would apply, in accordance with its Art. 27, only if the commercial agent acted in Belgium. Otherwise, general Belgian law would apply.

The decision

The CJEU decided that the parties may derogate from the Commercial Agency Directive if the agent acts in a third country (i.e. outside the EU). This has here been the case since the agent acted in Turkey.

The decision is particularly noteworthy because it – rather by the way – continues the CJEU’s Ingmar ruling under the Rome I Regulation (I.). In addition, it indirectly confirms sec. 92c of the German Commercial Code (II.) – which allows the parties to a commercial agent agreement governed by German law to deviate from the generally mandatory agency law if the commercial agent is acting outside the European Economic Area (“EEA”). Finally, it provides legal certainty for distribution outside the EEA and illustrates what may change after a Brexit as regards commercial agents acting in the United Kingdom (III.) – if the EU and the United Kingdom do not set up intertemporal arrangements for transition.

For details, please see the article by Benedikt Rohrßen, Zeitschrift für Vertriebsrecht 2017, 186 et seq. (“Ingmar reloaded – Handelsvertreter-Ausgleich bei umgekehrter Ingmar-Konstellation nicht international zwingend”).

Manufacturers of brand-name products typically aim to ensure the same level of quality of distribution throughout all distribution channels, offline and online. To achieve this aim, they provide criteria how to resell their products. With the increase of internet sales, the use of such criteria has been increasing as well.

A total ban of online sales to end consumers within the EU is, however, hardly valid because online sales are considered as passive sales (cf. Guidelines on Vertical Restraints 2010, para. 52). Restrictions below a total ban are, however, commonplace (for examples, see the post “eCommerce: restrictions on distributors in Germany”). Yet, it is still not clear how far such restrictions are permissible.

For example, the luxury perfume manufacturer Coty’s German subsidiary Coty Germany GmbH has set up a selective distribution network and its distributors may sell via the Internet, under the following conditions. They shall

- use their internet store as “electronic store window” of their brick and mortar store(s), thereby maintaining the products’ character as luxury goods, and

- abstain insofar from engaging third parties as such cooperation is externally visible.

The court of first instance decided that tsuch ban of sales via third party platforms was an unlawful restriction of competition under art. 101 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”), namely a hardcore restriction under article 4 lit. c Regulation (EU) No. 330/2010 (Vertical Block Exemptions Regulation or “VBER”). The court of second instance, however, does obviously not see the answer that clear. Instead, the court requested the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to give a preliminary ruling on how European antitrust rules have to be interpreted, namely article 101 TFEU and article 4 lit. b and c VBER (decision of 19.04.2016, ref. no. 11 U 96/14 [Kart]) – see the previous post “eCommerce: restrictions on distributors in Germany”.

On 30 March 2017, the hearing took place before the CJEU:

- Coty defended its platform ban, arguing it aimed at protecting the luxury image of brands such as Marc Jacobs, Calvin Klein or Chloe.

- France – seat of several luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Christian Dior –supported Coty.

- The distributor instead argued that established platforms such as Amazon and eBay already sold various brand-name products, e.g. of L’Oréal. Accordingly, there was no reason for Coty to ban the resale via these marketplaces. Germany also supported this view by emphasizing the importance of online platforms for small and medium-sized enterprises (where, however, the share of distributors using online marketplaces is 62% much higher than in all other Member States, see the Staff Working Document, „Final report on the E-commerce Sector Inquiry“, para. 452).

- Luxembourg – the seat of Amazon – considers a general platform ban to be disproportionate and therefore as anti-competitive (cf. Reuters’ article here).

Interest in the outcome of the Coty case is widespread, as the active participation of the various EU Member States illustrates (in addition to the abovementioned countries, also Italy, Sweden, the Netherlands and Austria). Simply put, the question is whether owners of luxury brands may generally or at least partially ban the resale via internet on third-party platforms.

Indications on how the court may decide have just appeared on 26 July 2017, with the Advocate General giving his opinion. The Advocate General proposes that the CJEU answers the questions referred to the court as follows:

“(1) Selective distribution systems relating to the distribution of luxury and prestige products and mainly intended to preserve the ‘luxury image’ of those products are an aspect of competition which is compatible with Article 101(1) TFEU provided that resellers are chosen on the basis of objective criteria of a qualitative nature which are determined uniformly for all and applied in a non-discriminatory manner for all potential resellers, that the nature of the product in question, including the prestige image, requires selective distribution in order to preserve the quality of the product and to ensure that it is correctly used, and that the criteria established do not go beyond what is necessary.

(2) In order to determine whether a contractual clause incorporating a prohibition on authorised distributors of a distribution network making use in a discernible manner of third-party platforms for online sales is compatible with Article 101(1) TFEU, it is for the referring court to examine whether that contractual clause is dependent on the nature of the product, whether it is determined in a uniform fashion and applied without distinction and whether it goes beyond what is necessary.

(3 The prohibition imposed on the members of a selective distribution system who operate as retailers on the market from making use in a discernible manner of third undertakings for internet sales does not constitute a restriction of the retailer’s customers within the meaning of Article 4(b) of Commission Regulation (EU) No 330/2010 of 20 April 2010 on the application of Article 101(3) on the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union to categories of vertical agreements and concerted practices.

(4) The prohibition imposed on the members of a selective distribution system, who operate as retailers on the market, from making use in a discernible manner of third undertakings for internet sales does not constitute a restriction of passive sales to end users within the meaning of Article 4(c) of Regulation No 330/2010.”

The Advocate General’s complete opinion can be found at CJEU’s website here.

The updated overview of the procedure can be found at CJEU’s website here.

Practical Conclusions

- The Coty case is extremely relevant to distribution in Europe because more than 70% of the world’s luxury items are sold here, many of them online now.

- The general ban to use price comparison tools shall be anti-competitive – according to the Bundeskartellamt, as confirmed by the Higher Regional Court of Düsseldorf on 5 April 2017. The last word is, however, still far from being said – see the post “Asics’ Distribution of Sporting Goods: Ban of Price Comparison Tools anti-competitive & void?!?”. Besides, also the Coty case’s outcome may influence how to see such bans.

- The Coty case is setting the course for future Internet sales. Depending on the decision of the CJEU, manufacturers of luxury or brand-name products can continue to ban the use of marketplaces like Amazon or eBay for the distribution of their products – or not any more or only under certain conditions. If the court follows the Advocate General’s conclusions, such platform bans appear possible, provided that the platform ban depends “on the nature of the product, whether it is determined in a uniform fashion and applied without distinction and whether it goes beyond what is necessary” (see above).

- For further trends in distribution online, see the EU Commission’s Final report on the E-commerce Sector Inquiry and details in the Staff Working Document, „Final report on the E-commerce Sector Inquiry“.

- For details on distribution networks and antitrust, please see my article „Plattformverbote im Selektivvertrieb – der EuGH-Vorlagebeschluss des OLG Frankfurt vom 19.4.2016“, in: Zeitschrift für Vertriebsrecht 2016, p. 278–283.

In distribution contracts, manufacturers and suppliers tend to restrict distributors in selling the goods online (I.). Though this practice is quite common, there is no clearly established rule if and which restrictions are allowed by antitrust law (II.), especially in case of luxury goods within selective distribution networks (III.).

Now, it is up to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to give a preliminary ruling on the internet sales restrictions (IV.). In the meantime, the question is: how to deal with resale restrictions now (V.).

Resale Restrictions in E-Commerce

E-Commerce keeps growing – worldwide and also in Germany, where it accounts for about 10% of total retail turnover (according to the 2016 figures from “Handelsverband Deutschland” [Trade Association of Germany]). Also manufacturers of renowned brands try to take advantage of the market opportunities of e-commerce, and at the same time try to preserve their brand’s image. Consequently, manufacturers have imposed several kinds of restrictions on their distributors, in particular:

- total ban of internet sales,

- prohibition of sales via third parties’ online platforms (especially “marketplaces”),

- operation of a brick and mortar shops as a prerequisite for internet sales,

- dual pricing, or

- quality criteria for internet sales.

Antitrust limits to online resale restrictions

Antitrust authorities, however, however, have lately put such restrictions under scrutiny and enforce antitrust rules in e-commerce as well. Accordingly, there have been quite a few court judgments and antitrust authorities’ decisions, both in favour of and against such restrictions, e.g. on:

- bags (“Scout” re third party platforms),

- sportswear (“Asics”re price comparisons, logo clause, “Adidas” re third party platforms),

- electronics (“Sennheiser” and “Casio”both re third party platforms),

- luxury cosmetics / perfumes (“Coty” re price comparisons, third platforms), or

- software (“Google” requiring manufacturers of to pre-install apps, cf. European Commission’s press release of 20 April 2016).

Now, the luxury cosmetics case of Coty Germany has reached the European level.

The current Coty Case

Facts of the case are as follows: The supplier (Coty Germany GmbH) has set up a selective distribution network. Distributors may sell via internet, under the following restrictions. They shall

- use their internet store as “electronic store window” of their brick and mortar store(s), thereby maintaining the products’ character as luxury goods, and

- abstain insofar from engaging third parties as such cooperation is externally visible.

The parties’ intentions: The supplier wants to enforce especially the last restriction, stopping a distributor (Parfümerie Akzente GmbH) from selling supplier’s products via Amazon’s marketplace. The distributor, obviously, intends to be free from such restrictions.

The court of first instance, the district court of Frankfurt, decided that the ban of sales via third party platforms is an unlawful restriction of competition under article 101 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”), namely a hardcore restriction under article 4 lit. c Regulation (EU) No. 330/2010 (Vertical Block Exemptions Regulation or “VBER”). The court of second instance, the Higher Regional Court of Frankfurt, however, does obviously not see the answer that clear. Therefore, the court has requested the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to give a preliminary ruling on how European antitrust rules have to be interpreted, namely article 101 TFEU and article 4 lit. b and c VBER (decision of 19.04.2016, ref. no. 11 U 96/14 [Kart]).

Questions referred to the CJEU

The CJEU has filed the case as “Coty Germany” (reference no. C-230/16). These are the four questions on which the CJEU is requested to answer:

- Do selective distribution systems that have as their aim the distribution of luxury goods and primarily serve to ensure a ‘luxury image’ for the goods constitute an aspect of competition that is compatible with Article 101(1) TFEU?

If the first question is answered in the affirmative:

- Does it constitute an aspect of competition that is compatible with Article 101(1) TFEU if the members of a selective distribution system operating at the retail level of trade are prohibited generally from engaging third-party undertakings discernible to the public to handle internet sales, irrespective of whether the manufacturer’s legitimate quality standards are contravened in the specific case?

- Is Article 4(b) of Regulation (EU) No 330/2010 to be interpreted as meaning that a prohibition of engaging thirdparty undertakings discernible to the public to handle internet sales that is imposed on the members of a selective distribution system operating at the retail level of trade constitutes a restriction of the retailer’s customer group ‘by object’?

- Is Article 4(c) of Regulation (EU) No 330/2010 to be interpreted as meaning that a prohibition of engaging third-party undertakings discernible to the public to handle internet sales that is imposed on the members of a selective distribution system operating at the retail level of trade constitutes a restriction of passive sales to end users ‘by object’?

How to deal with Restrictions now

There is quite some case law in Germany about the ban on online sales, some decisions in favour, some against. Online sales restrictions have lately also been under scrutiny of the German Bundeskartellamt (federal antitrust authority), which in general rather takes a critical position against such restrictions, including restrictions on selling via third-party platforms.

A decision of the highest German court is, however, still missing. Still missing is therefore also a clear answer to the question which restrictions suppliers and distributors can validly agree upon, especially in case of luxury goods. The CJEU’s preliminary ruling should provide such clarity.

Until the CJEU’s preliminary ruling, the current legal situation should be as follows – based especially on the Guidelines on Vertical Restraints 2010 (which do not have the quality of a law and do not bind the courts, but set out the principles which guide the European Commission’s assessment of vertical agreements and thus in principle bind the European Commission itself):

- A total ban of online sales is hardly valid because online sales are considered as passive sales (cf. Guidelines on Vertical Restraints 2010, para. 52). Hardly an option either is restricting the webstore’s language options because it does not change the passive character of such selling (cf. Guidelines on Vertical Restraints 2010, para. 52). The same goes for restrictions on the turnover made by sales via the internet.

- Allowed should, however, especially be

- qualitative requirements for the design of e-commerce platform (without resulting in a total ban and without restricting the use of languages),

- the restriction of active sales into the exclusive territory or to an exclusive customer group reserved to the supplier or allocated by the supplier to another buyer (article 4 lit. b (i) VBER), e.g. territory-based banners on third party websites, cf. Guidelines on Vertical Restraints 2010, para. 53),

- general qualitative restrictions for becoming a member of the supplier’s selective distribution system, e.g. requiring that distributors have one or more brick and mortar shops or showrooms (Guidelines on Vertical Restraints 2010, para. 54, 176).

The CJEU’s decision will bring more clarity – Legalmondo will keep you updated on the Coty Case and possible implications on online distribution.

“E-commerce and omni-channel distribution in China: everyone talks about it, no one knows how it really works” (@Stevie Kim, Vinitaly International)

Assistiamo in questi tempi ad un proliferare di iniziative dedicate allo sbarco delle imprese italiane sulle principali piattaforme di e-commerce cinesi, ma la conoscenza di chi sono i protagonisti, come funziona questo nuovo mercato, con quali regole e costi, e soprattutto, qual è il segreto per avere successo, è ancora molto limitata.

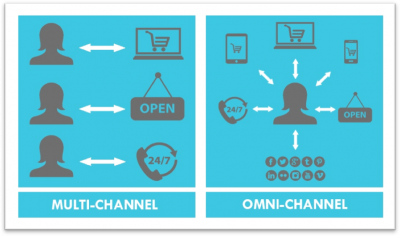

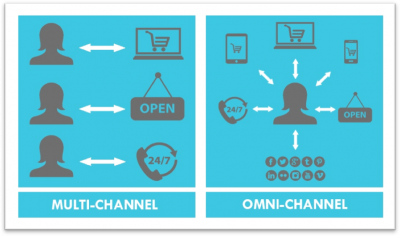

Omni-channel, cross-channel, online to offline (“O2O”) sono termini inflazionati, che vengono spesso usati a sproposito: per iniziare, dunque, di cosa stiamo parlando?

Secondo Wikipedia “Omnichannel is a cross-channel business model that companies use to increase customer experience (…) including channels such as physical locations, FAQ webpages, social media, live web chats, mobile applications and telephone communication. Companies that use omnichannel contend that a customer values the ability to be in constant contact with a company through multiple avenues at the same time”.

Possiamo sintetizzare dunque il concetto di omni-channel o cross channel come la creazione di un sistema di promozione e vendita dei prodotti attraverso diversi canali, tra loro integrati, con l’obiettivo di raggiungere il consumatore/cliente e di consentirgli un passaggio senza soluzione di continuità tra sito web aziendale, piattaforme di e-commerce specializzate su una certa tipologia di prodotti (c.d. “verticali”) o generaliste (“orizzontali”), punti vendita fisici, social media, campagne di marketing ed eventi di promozione tradizionali e/o digitali.

Omni-channel, dunque, non è un sinonimo di e-commerce ma descrive un sistema molto più complesso, che richiede una chiara strategia di comunicazione, promozione e vendita dei prodotti, che non può prescindere da un’azione integrata su vari canali, tra i quali è fondamentale quello “tradizionale” o fisico.

Aprire un virtual store o riuscire ad avere una presenza dei prodotti su Tmall o JD.com, senza aver elaborato una strategia omni-channel spesso comporta costi altissimi di start up e gestione, che l’impresa straniera non può sostenere nel medio termine, specie se le vendite dei prodotti, come spesso accade, fanno fatica a decollare.

Basti pensare, a questo proposito, che solo su Tmall Global sono presenti 14.500 brand stranieri, l’80% dei quali si affaccia per la prima volta al mercato cinese (fonte CBN Data and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd): la concorrenza è altissima e attrarre traffico e ottenere visibilità è molto costoso e richiede una grande esperienza di marketing sul mercato cinese.

Testimone del trend sempre più spinto Online to Offline è la recente acquisizione da parte di Alibaba Group Holding della catena di department stores Intime Retail Group Co. per 2,6 mld di dollari, operazione che fa seguito ad altri rilevanti investimenti nel settore della distribuzione tradizionale (Suning e Haier).

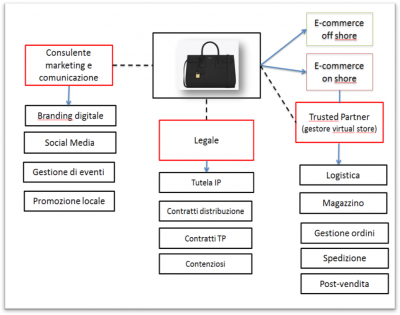

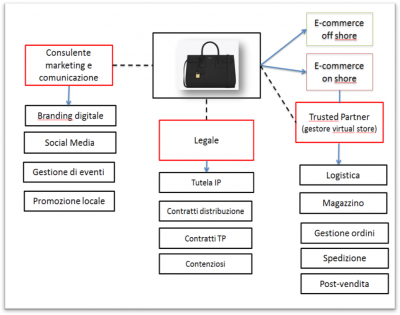

È imprescindibile, dunque, avere le idee chiare e una solida strategia, che si traduca in un business plan focalizzato sulla distribuzione omni-channel, messo a punto con consulenti esperti del mercato cinese nelle diverse aree di attività coinvolte: con un po’ di semplificazione il quadro potrebbe essere rappresentato così:

Gli aspetti da considerare sono molteplici: tutela del marchio, import dei prodotti, magazzino e logistica, accordi contrattuali con il gestore del virtual store e con i distributori online e offline, gestione dell’attività di promozione su internet e social media, customer care.

Tratteremo in una serie di articoli i punti principali per preparare in modo professionale e completo una strategia efficace di distribuzione omni-channel in Cina:

- Marchio, dominio web, account social media: la protezione della proprietà intellettuale

- L’import dei prodotti in Cina

- Come scegliere il distributore

- Adempimenti e costi di apertura e gestione di un virtual store

- Come si concilia la distribuzione tradizionale con quella e-commerce on shore e off shore

- Come negoziare e redigere un contratto di vendita e di distribuzione in Cina

- La normativa a tutela del consumatore

- La gestione dei contenziosi

Scrivi a Benedikt

Distribution online – Platform bans in selective distribution (The Coty case continues)

15 Agosto 2017

-

Germania

- Distribuzione

- eCommerce

I produttori di articoli di marca tipicamente puntano ad assicurare lo stesso livello di qualità lungo tutti i canali di distribuzione. Al fine di conseguire tale scopo, essi stabiliscono criteri su come rivendere i propri prodotti. Con l’aumento delle vendite via internet, l’utilizzo di tali criteri è aumentato altrettanto.

Il miglior esempio: Asics. Fino al 2010, la controllata tedesca Asics Deutschland GmbH riforniva i propri distributori in Germania senza applicare criteri particolari. Nel 2011, Asics ha lanciato un sistema di distribuzione selettivo chiamato “Distribution System 1.0“. Esso prevede, tra le altre cose, un divieto generale, per i distributori, di usare strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi nelle vendite online:

“In aggiunta, il distributore autorizzato … non è da ritenersi autorizzato … a supportare la funzionalità di comparazione dei prezzi apportando l’interfaccia specifica d’applicazione (“API”) per tali strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi.” [tradotto]

L’Ufficio federale dei cartelli tedesco (“Bundeskartellamt”) ha stabilito, con decisione del 26 agosto 2015, che il divieto di utilizzare strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi nei confronti di distributori presenti in Germania era nullo in quanto viola l’articolo 101 (1) TFUE e l’art. 1 della Legge contro le limitazioni della concorrenza (cfr. il testo della decisione, di 196 pagine, qui). Il motivo addotto è che tale divieto punterebbe principalmente a controllare e limitare la competizione dei prezzi a spese del consumatore. Asics, per contro, ha presentato ricorso dinnanzi all’Alta Corte Regionale di Düsseldorf, al fine di vedere annullata la decisione dell’Ufficio federale dei cartelli, sostenendo che tale divieto era uno standard di qualità proporzionato nell’ambito del suo “Distribution System 1.0“, mirante a una presentazione uniforme dei prodotti.

Il 5 aprile 2017, l’Alta Corte Regionale di Düsseldorf ha confermato, così come la decisione dell’Ufficio federale dei cartelli, che nell’ambito di sistemi di distribuzione selettiva il divieto generale di usare strumenti comparazione dei prezzi era anticoncorrenziale e con ciò nullo (fasc. n. VI-Kart 13/15 (V); vedi altresì la rassegna stampa dell’Ufficio federale dei cartelli in inglese):

- In particolare, il divieto di strumentazione di comparazione dei prezzi non era dispensato, nell’ambito di una interpretazione teleologica (“Tatbestandsreduktion”), dall’art. 101 co. 1 TFEU. Secondo la Corte, ciò non era necessario al fine di proteggere la qualità e l’immagine di prodotto del brand Asics (ossia la stessa argomentazione dell’Alta Corte regionale di Francoforte nella sua sentenza del 22.12.2015, fasc. n. 11 U 84/14 riguardante gli zaini di Deuter; la Corte suprema federale non dovrà più decidere su tale caso perché la revisione è stata ritirata in marzo 2017, fasc. n. KZR 3/16). La Corte ha dichiarato che il divieto era volto a limitare i compratori, argomentando che i distributori sarebbero stati limitati nell’entrare in una competizione sui prezzi con altri. La presentazione di prodotti all’interno degli strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi non avrebbe danneggiato la qualità o il brand di prodotti Asics. Non avrebbe nemmeno dato “l’impressione di un mercato delle pulci”, nemmeno attraverso la presentazione, in parallelo, di prodotti usati. Inoltre, il divieto di strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi non risolverebbe comunque il problema del “free-riding”. In ogni caso, il divieto generale posto all’utilizzo di strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi non era necessario e perciò illegittimo.

- Il divieto, inoltre, non doveva ritenersi esentato dal regolamento sulle categorie di accordi verticali e pratiche concordate. Al contrario, la Corte ha rilevato che il divieto avrebbe limitato vendite passive (svolte cioè attraverso internet) verso consumatori finali, contrariamente all’art. 4 (c) del regolamento sulle categorie di accordi verticali e pratiche concordate (facendo riferimento alla decisione della Corte di Giustizia dell’UE nel caso di Pierre Fabre, 13 ottobre 2011, fasc. n. C-439/09). Il “principio di equivalenza” (secondo cui le restrizioni valide per le vendite offline così come online non dovrebbero essere identiche, ma funzionalmente equivalenti) non si applicherebbe, in quanto nel commercio tradizionale non ci sarebbero funzioni comparabili agli strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi.

- Infine, il divieto non beneficerebbe nemmeno dell’esenzione individuale di cui all’art. 101 co. 3 TFUE (“difesa dell’efficienza”).

Conclusioni

Secondo l’Alta Corte regionale di Düsseldorf, i produttori non potrebbero proibire generalmente ai loro distributori di usare strumenti di comparazione dei prezzi. Allo stesso tempo, la corte ha rifiutato di concedere l’autorizzazione a un appello contro la propria decisione – che, comunque, può essere richiesto separatamente, tramite la via dell’impugnazione (cfr. artt. 74, 75 della Legge contro le restrizioni in materia di concorrenza). Il futuro sviluppo di criteri limitanti i distributori nella rivendita online resta aperto, in particolare in quanto (i) il caso Coty è attualmente pendente presso la Corte di Giustizia dell’UE (vedi sotto) e (ii) la Commissione UE nella sua inchiesta di settore sull’e-commerce apparentemente sembra favorire i produttori di articoli di marca (vedi sotto).

- La Corte ha lasciato esplicitamente aperte – adducendo che non fossero rilevanti per la sua decisione – la questioni se:

- il divieto di motori di ricerca sia anti competitivo (paragrafo 44 e ss. della decisione);

- il divieto generale di usare piattaforme di terze parti sia anti competitivo (paragrafo 7) – sebbene il “Distribution System 1.0” di Asics vietasse anche piattaforme come Amazon e eBay.

- Se e come produttori di prodotti di lusso o di marca possono continuare a vietare la loro distribuzione via Amazon, eBay e altri mercati in generale verrà probabilmente deciso dalla Corte di Giustizia UE nei prossimi mesi – nel caso Coty (vedi il nostro post “eCommerce: restrizioni su distributori in Germania”) per il quale un’udienza ha già avuto luogo alla fine di marzo 2017.

- Senza pregiudizio per il caso Coty, la Commissione UE, nella propria inchiesta di settore sull’e-commerce del maggio 2017, dichiarato che

- “divieti di marketplaces in generale non producono una proibizione di fatto della vendita online, non restringono l’uso effettivo di internet come canale di vendita indipendentemente dai mercati colpiti dal divieto…”;

- “la potenziale giustificazione ed efficienze riportate dai produttori differiscono da un prodotto all’altro …”;

- “(assoluti) divieti di marketplaces non dovrebbero essere considerati quali restrizioni fondamentali nel significato dell’articolo 4(b) e articolo 4(c) del regolamento su categorie di accordi verticali e pratiche concordate …”;

- “la Commissione o una autorità nazionale della concorrenza potrebbe decidere di ritirare la protezione del regolamento su categorie di accordi verticali e pratiche concordate in casi particolari, se giustificato dalla situazione di mercato”

(41–43 del Report finale sull’inchiesta di settore sull’e-commerce).

- Per dettagli sulla distribuzione online e il diritto antitrust, si prega di consultare il mio ultimo articolo “Internetvertrieb in der EU 2018 ff. – Online-Vertriebsvorgaben von Asics über BMW bis Coty”, in: Zeitschrift für Vertriebsrecht 2017, pp. 274-281.

Perciò, sulla base della più recente posizione della Commissione Europea, vi è spazio per argomenti e per la redazione creativa di contratti, posto che anche divieti generali di mercato possono essere compatibili con le norme UE sulla concorrenza. Comunque, le corti potrebbero considerare la questione in modo differente nel singolo caso. Conseguentemente, soprattutto la Corte di Giustizia UE con il suo caso Coty (vedi sopra) porterà maggiore chiarezza per la futura distribuzione online. Sul caso Coty, la Corte di Giustizia UE deciderà il 6 dicembre 2017 (vedi il calendario giudiziario della Corte) : rimanete aggiornati sugli sviluppi seguendo il nostro blog.

The Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) has issued a new ruling on the international scope of the Commercial Agency Directive (86/653/EEC of 18 December 1986). The new decision is in line with the rulings of

- the CJEU in the Ingmar case (decision of 9 November 2000, C-381/98, goodwill indemnity mandatory where the agent acts within the EU) and Unamar (decision of 17 October 2013, C-184/12, as to whether national agency law is mandatory where exceeding the Commercial Agency Directive’s minimum protection) and

- the German Federal Supreme Court of 5 September 2012 (German agency law as mandatory law vis-à-vis suppliers in third countries with choice-of-court clause).

The question

Now, the CJEU had to decide whether a commercial agent acting in Turkey for a supplier based in Belgium could claim goodwill indemnity on the basis of the Commercial Agency Directive. More specifically, the question was whether the territorial scope of the Commercial Agency Directive was given where the commercial agent acts in a third country and the supplier within the EU – hence opposite to the Ingmar case.

The facts

According to the agency contract, Belgian law applied and the courts in Gent (Belgium) should be competent. Belgian law, transposing the Commercial Agency Directive, provides for a goodwill indemnity claim at termination of the contract (and, additionally, compensation for damages). However, the referring court considered that the Belgian Law on Commercial Agents of 1995 was self-restraining and would apply, in accordance with its Art. 27, only if the commercial agent acted in Belgium. Otherwise, general Belgian law would apply.

The decision

The CJEU decided that the parties may derogate from the Commercial Agency Directive if the agent acts in a third country (i.e. outside the EU). This has here been the case since the agent acted in Turkey.

The decision is particularly noteworthy because it – rather by the way – continues the CJEU’s Ingmar ruling under the Rome I Regulation (I.). In addition, it indirectly confirms sec. 92c of the German Commercial Code (II.) – which allows the parties to a commercial agent agreement governed by German law to deviate from the generally mandatory agency law if the commercial agent is acting outside the European Economic Area (“EEA”). Finally, it provides legal certainty for distribution outside the EEA and illustrates what may change after a Brexit as regards commercial agents acting in the United Kingdom (III.) – if the EU and the United Kingdom do not set up intertemporal arrangements for transition.

For details, please see the article by Benedikt Rohrßen, Zeitschrift für Vertriebsrecht 2017, 186 et seq. (“Ingmar reloaded – Handelsvertreter-Ausgleich bei umgekehrter Ingmar-Konstellation nicht international zwingend”).

Manufacturers of brand-name products typically aim to ensure the same level of quality of distribution throughout all distribution channels, offline and online. To achieve this aim, they provide criteria how to resell their products. With the increase of internet sales, the use of such criteria has been increasing as well.

A total ban of online sales to end consumers within the EU is, however, hardly valid because online sales are considered as passive sales (cf. Guidelines on Vertical Restraints 2010, para. 52). Restrictions below a total ban are, however, commonplace (for examples, see the post “eCommerce: restrictions on distributors in Germany”). Yet, it is still not clear how far such restrictions are permissible.

For example, the luxury perfume manufacturer Coty’s German subsidiary Coty Germany GmbH has set up a selective distribution network and its distributors may sell via the Internet, under the following conditions. They shall

- use their internet store as “electronic store window” of their brick and mortar store(s), thereby maintaining the products’ character as luxury goods, and

- abstain insofar from engaging third parties as such cooperation is externally visible.

The court of first instance decided that tsuch ban of sales via third party platforms was an unlawful restriction of competition under art. 101 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”), namely a hardcore restriction under article 4 lit. c Regulation (EU) No. 330/2010 (Vertical Block Exemptions Regulation or “VBER”). The court of second instance, however, does obviously not see the answer that clear. Instead, the court requested the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to give a preliminary ruling on how European antitrust rules have to be interpreted, namely article 101 TFEU and article 4 lit. b and c VBER (decision of 19.04.2016, ref. no. 11 U 96/14 [Kart]) – see the previous post “eCommerce: restrictions on distributors in Germany”.

On 30 March 2017, the hearing took place before the CJEU:

- Coty defended its platform ban, arguing it aimed at protecting the luxury image of brands such as Marc Jacobs, Calvin Klein or Chloe.

- France – seat of several luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Christian Dior –supported Coty.

- The distributor instead argued that established platforms such as Amazon and eBay already sold various brand-name products, e.g. of L’Oréal. Accordingly, there was no reason for Coty to ban the resale via these marketplaces. Germany also supported this view by emphasizing the importance of online platforms for small and medium-sized enterprises (where, however, the share of distributors using online marketplaces is 62% much higher than in all other Member States, see the Staff Working Document, „Final report on the E-commerce Sector Inquiry“, para. 452).

- Luxembourg – the seat of Amazon – considers a general platform ban to be disproportionate and therefore as anti-competitive (cf. Reuters’ article here).

Interest in the outcome of the Coty case is widespread, as the active participation of the various EU Member States illustrates (in addition to the abovementioned countries, also Italy, Sweden, the Netherlands and Austria). Simply put, the question is whether owners of luxury brands may generally or at least partially ban the resale via internet on third-party platforms.

Indications on how the court may decide have just appeared on 26 July 2017, with the Advocate General giving his opinion. The Advocate General proposes that the CJEU answers the questions referred to the court as follows:

“(1) Selective distribution systems relating to the distribution of luxury and prestige products and mainly intended to preserve the ‘luxury image’ of those products are an aspect of competition which is compatible with Article 101(1) TFEU provided that resellers are chosen on the basis of objective criteria of a qualitative nature which are determined uniformly for all and applied in a non-discriminatory manner for all potential resellers, that the nature of the product in question, including the prestige image, requires selective distribution in order to preserve the quality of the product and to ensure that it is correctly used, and that the criteria established do not go beyond what is necessary.

(2) In order to determine whether a contractual clause incorporating a prohibition on authorised distributors of a distribution network making use in a discernible manner of third-party platforms for online sales is compatible with Article 101(1) TFEU, it is for the referring court to examine whether that contractual clause is dependent on the nature of the product, whether it is determined in a uniform fashion and applied without distinction and whether it goes beyond what is necessary.

(3 The prohibition imposed on the members of a selective distribution system who operate as retailers on the market from making use in a discernible manner of third undertakings for internet sales does not constitute a restriction of the retailer’s customers within the meaning of Article 4(b) of Commission Regulation (EU) No 330/2010 of 20 April 2010 on the application of Article 101(3) on the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union to categories of vertical agreements and concerted practices.

(4) The prohibition imposed on the members of a selective distribution system, who operate as retailers on the market, from making use in a discernible manner of third undertakings for internet sales does not constitute a restriction of passive sales to end users within the meaning of Article 4(c) of Regulation No 330/2010.”

The Advocate General’s complete opinion can be found at CJEU’s website here.

The updated overview of the procedure can be found at CJEU’s website here.

Practical Conclusions

- The Coty case is extremely relevant to distribution in Europe because more than 70% of the world’s luxury items are sold here, many of them online now.

- The general ban to use price comparison tools shall be anti-competitive – according to the Bundeskartellamt, as confirmed by the Higher Regional Court of Düsseldorf on 5 April 2017. The last word is, however, still far from being said – see the post “Asics’ Distribution of Sporting Goods: Ban of Price Comparison Tools anti-competitive & void?!?”. Besides, also the Coty case’s outcome may influence how to see such bans.

- The Coty case is setting the course for future Internet sales. Depending on the decision of the CJEU, manufacturers of luxury or brand-name products can continue to ban the use of marketplaces like Amazon or eBay for the distribution of their products – or not any more or only under certain conditions. If the court follows the Advocate General’s conclusions, such platform bans appear possible, provided that the platform ban depends “on the nature of the product, whether it is determined in a uniform fashion and applied without distinction and whether it goes beyond what is necessary” (see above).

- For further trends in distribution online, see the EU Commission’s Final report on the E-commerce Sector Inquiry and details in the Staff Working Document, „Final report on the E-commerce Sector Inquiry“.

- For details on distribution networks and antitrust, please see my article „Plattformverbote im Selektivvertrieb – der EuGH-Vorlagebeschluss des OLG Frankfurt vom 19.4.2016“, in: Zeitschrift für Vertriebsrecht 2016, p. 278–283.

In distribution contracts, manufacturers and suppliers tend to restrict distributors in selling the goods online (I.). Though this practice is quite common, there is no clearly established rule if and which restrictions are allowed by antitrust law (II.), especially in case of luxury goods within selective distribution networks (III.).

Now, it is up to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to give a preliminary ruling on the internet sales restrictions (IV.). In the meantime, the question is: how to deal with resale restrictions now (V.).

Resale Restrictions in E-Commerce

E-Commerce keeps growing – worldwide and also in Germany, where it accounts for about 10% of total retail turnover (according to the 2016 figures from “Handelsverband Deutschland” [Trade Association of Germany]). Also manufacturers of renowned brands try to take advantage of the market opportunities of e-commerce, and at the same time try to preserve their brand’s image. Consequently, manufacturers have imposed several kinds of restrictions on their distributors, in particular:

- total ban of internet sales,

- prohibition of sales via third parties’ online platforms (especially “marketplaces”),

- operation of a brick and mortar shops as a prerequisite for internet sales,

- dual pricing, or

- quality criteria for internet sales.

Antitrust limits to online resale restrictions

Antitrust authorities, however, however, have lately put such restrictions under scrutiny and enforce antitrust rules in e-commerce as well. Accordingly, there have been quite a few court judgments and antitrust authorities’ decisions, both in favour of and against such restrictions, e.g. on:

- bags (“Scout” re third party platforms),

- sportswear (“Asics”re price comparisons, logo clause, “Adidas” re third party platforms),

- electronics (“Sennheiser” and “Casio”both re third party platforms),

- luxury cosmetics / perfumes (“Coty” re price comparisons, third platforms), or

- software (“Google” requiring manufacturers of to pre-install apps, cf. European Commission’s press release of 20 April 2016).

Now, the luxury cosmetics case of Coty Germany has reached the European level.

The current Coty Case

Facts of the case are as follows: The supplier (Coty Germany GmbH) has set up a selective distribution network. Distributors may sell via internet, under the following restrictions. They shall

- use their internet store as “electronic store window” of their brick and mortar store(s), thereby maintaining the products’ character as luxury goods, and

- abstain insofar from engaging third parties as such cooperation is externally visible.

The parties’ intentions: The supplier wants to enforce especially the last restriction, stopping a distributor (Parfümerie Akzente GmbH) from selling supplier’s products via Amazon’s marketplace. The distributor, obviously, intends to be free from such restrictions.

The court of first instance, the district court of Frankfurt, decided that the ban of sales via third party platforms is an unlawful restriction of competition under article 101 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”), namely a hardcore restriction under article 4 lit. c Regulation (EU) No. 330/2010 (Vertical Block Exemptions Regulation or “VBER”). The court of second instance, the Higher Regional Court of Frankfurt, however, does obviously not see the answer that clear. Therefore, the court has requested the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to give a preliminary ruling on how European antitrust rules have to be interpreted, namely article 101 TFEU and article 4 lit. b and c VBER (decision of 19.04.2016, ref. no. 11 U 96/14 [Kart]).

Questions referred to the CJEU

The CJEU has filed the case as “Coty Germany” (reference no. C-230/16). These are the four questions on which the CJEU is requested to answer:

- Do selective distribution systems that have as their aim the distribution of luxury goods and primarily serve to ensure a ‘luxury image’ for the goods constitute an aspect of competition that is compatible with Article 101(1) TFEU?

If the first question is answered in the affirmative:

- Does it constitute an aspect of competition that is compatible with Article 101(1) TFEU if the members of a selective distribution system operating at the retail level of trade are prohibited generally from engaging third-party undertakings discernible to the public to handle internet sales, irrespective of whether the manufacturer’s legitimate quality standards are contravened in the specific case?

- Is Article 4(b) of Regulation (EU) No 330/2010 to be interpreted as meaning that a prohibition of engaging thirdparty undertakings discernible to the public to handle internet sales that is imposed on the members of a selective distribution system operating at the retail level of trade constitutes a restriction of the retailer’s customer group ‘by object’?

- Is Article 4(c) of Regulation (EU) No 330/2010 to be interpreted as meaning that a prohibition of engaging third-party undertakings discernible to the public to handle internet sales that is imposed on the members of a selective distribution system operating at the retail level of trade constitutes a restriction of passive sales to end users ‘by object’?

How to deal with Restrictions now

There is quite some case law in Germany about the ban on online sales, some decisions in favour, some against. Online sales restrictions have lately also been under scrutiny of the German Bundeskartellamt (federal antitrust authority), which in general rather takes a critical position against such restrictions, including restrictions on selling via third-party platforms.

A decision of the highest German court is, however, still missing. Still missing is therefore also a clear answer to the question which restrictions suppliers and distributors can validly agree upon, especially in case of luxury goods. The CJEU’s preliminary ruling should provide such clarity.

Until the CJEU’s preliminary ruling, the current legal situation should be as follows – based especially on the Guidelines on Vertical Restraints 2010 (which do not have the quality of a law and do not bind the courts, but set out the principles which guide the European Commission’s assessment of vertical agreements and thus in principle bind the European Commission itself):

- A total ban of online sales is hardly valid because online sales are considered as passive sales (cf. Guidelines on Vertical Restraints 2010, para. 52). Hardly an option either is restricting the webstore’s language options because it does not change the passive character of such selling (cf. Guidelines on Vertical Restraints 2010, para. 52). The same goes for restrictions on the turnover made by sales via the internet.

- Allowed should, however, especially be

- qualitative requirements for the design of e-commerce platform (without resulting in a total ban and without restricting the use of languages),

- the restriction of active sales into the exclusive territory or to an exclusive customer group reserved to the supplier or allocated by the supplier to another buyer (article 4 lit. b (i) VBER), e.g. territory-based banners on third party websites, cf. Guidelines on Vertical Restraints 2010, para. 53),

- general qualitative restrictions for becoming a member of the supplier’s selective distribution system, e.g. requiring that distributors have one or more brick and mortar shops or showrooms (Guidelines on Vertical Restraints 2010, para. 54, 176).

The CJEU’s decision will bring more clarity – Legalmondo will keep you updated on the Coty Case and possible implications on online distribution.

“E-commerce and omni-channel distribution in China: everyone talks about it, no one knows how it really works” (@Stevie Kim, Vinitaly International)

Assistiamo in questi tempi ad un proliferare di iniziative dedicate allo sbarco delle imprese italiane sulle principali piattaforme di e-commerce cinesi, ma la conoscenza di chi sono i protagonisti, come funziona questo nuovo mercato, con quali regole e costi, e soprattutto, qual è il segreto per avere successo, è ancora molto limitata.

Omni-channel, cross-channel, online to offline (“O2O”) sono termini inflazionati, che vengono spesso usati a sproposito: per iniziare, dunque, di cosa stiamo parlando?

Secondo Wikipedia “Omnichannel is a cross-channel business model that companies use to increase customer experience (…) including channels such as physical locations, FAQ webpages, social media, live web chats, mobile applications and telephone communication. Companies that use omnichannel contend that a customer values the ability to be in constant contact with a company through multiple avenues at the same time”.

Possiamo sintetizzare dunque il concetto di omni-channel o cross channel come la creazione di un sistema di promozione e vendita dei prodotti attraverso diversi canali, tra loro integrati, con l’obiettivo di raggiungere il consumatore/cliente e di consentirgli un passaggio senza soluzione di continuità tra sito web aziendale, piattaforme di e-commerce specializzate su una certa tipologia di prodotti (c.d. “verticali”) o generaliste (“orizzontali”), punti vendita fisici, social media, campagne di marketing ed eventi di promozione tradizionali e/o digitali.

Omni-channel, dunque, non è un sinonimo di e-commerce ma descrive un sistema molto più complesso, che richiede una chiara strategia di comunicazione, promozione e vendita dei prodotti, che non può prescindere da un’azione integrata su vari canali, tra i quali è fondamentale quello “tradizionale” o fisico.

Aprire un virtual store o riuscire ad avere una presenza dei prodotti su Tmall o JD.com, senza aver elaborato una strategia omni-channel spesso comporta costi altissimi di start up e gestione, che l’impresa straniera non può sostenere nel medio termine, specie se le vendite dei prodotti, come spesso accade, fanno fatica a decollare.

Basti pensare, a questo proposito, che solo su Tmall Global sono presenti 14.500 brand stranieri, l’80% dei quali si affaccia per la prima volta al mercato cinese (fonte CBN Data and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd): la concorrenza è altissima e attrarre traffico e ottenere visibilità è molto costoso e richiede una grande esperienza di marketing sul mercato cinese.

Testimone del trend sempre più spinto Online to Offline è la recente acquisizione da parte di Alibaba Group Holding della catena di department stores Intime Retail Group Co. per 2,6 mld di dollari, operazione che fa seguito ad altri rilevanti investimenti nel settore della distribuzione tradizionale (Suning e Haier).

È imprescindibile, dunque, avere le idee chiare e una solida strategia, che si traduca in un business plan focalizzato sulla distribuzione omni-channel, messo a punto con consulenti esperti del mercato cinese nelle diverse aree di attività coinvolte: con un po’ di semplificazione il quadro potrebbe essere rappresentato così:

Gli aspetti da considerare sono molteplici: tutela del marchio, import dei prodotti, magazzino e logistica, accordi contrattuali con il gestore del virtual store e con i distributori online e offline, gestione dell’attività di promozione su internet e social media, customer care.

Tratteremo in una serie di articoli i punti principali per preparare in modo professionale e completo una strategia efficace di distribuzione omni-channel in Cina:

- Marchio, dominio web, account social media: la protezione della proprietà intellettuale

- L’import dei prodotti in Cina

- Come scegliere il distributore

- Adempimenti e costi di apertura e gestione di un virtual store

- Come si concilia la distribuzione tradizionale con quella e-commerce on shore e off shore

- Come negoziare e redigere un contratto di vendita e di distribuzione in Cina

- La normativa a tutela del consumatore

- La gestione dei contenziosi