-

Cina

Cina – Distribuzione Omnichannel

28 Gennaio 2017

- eCommerce

- Distribuzione

Chinese outbound M&A was one of the main topics of interest at the 2017 Hong Kong IFLR Forum on M&A in Asia, a great event with an outstanding level of speakers and very interesting discussions on various themes related to international investments.

All the attendants shared the view that momentum for Chinese overseas investments is still strong, despite the recent policy aiming at curbing the outflow of capitals from China.

A particularly interesting session was that on “best practices to overcome credibility and experience gaps increasingly faced by “off the radar” Chinese bidders”.

Opening a one-to-one negotiation or letting a Chinese company bid at an auction involves often great deal of uncertainty, as most participants to the session shared the experience of having seeing their Chinese counterpart walk away from the negotiation without any explanation (the so-called “Random Investors”).

I have scribbled down the take-aways of the discussion as follows.

Main clues to spot early on the Random investor:

- the Company pops out from nowhere and has no track record of overseas investments;

- the Company has no legal or financial advisors, or if they do, their advisors are not experienced in overseas transactions;

- the Company has excellent advisors… but has not paid their fees (yes, that happens)

- the target does not belong to the Company’s core business (and there is no explanation for their interest for the deal);

What should you do to be on the safe side?

- request a written declaration of interest, expressing the reasons why the Company wants to invest in the target and what is their mid term strategy, signed and stamped by the legal representative (if they are not ready to hand over this letter the game can stop here).

- If the Company represents a group of investors, require full disclosure and letters of confirmation from all parties, from day one (AC Milan’s case is a good example of what happens later on if there is no disclosure of all players, and their stakes in the deal);

- request proof that the Company has filed the application for the authorisation to invest overseas (due to the recent tightening of controls on capital outflow, this step is fundamental);

- request proof that they have the finance needed for the deal (either onshore or, better, off-shore);

- make clear that you will require a “break fee” (which can vary from 5 to 10%) in case they walk away from the negotiation (we have heard of US companies expecting 30 to 50% break fee on the value of the deal…)

“E-commerce and omni-channel distribution in China: everyone talks about it, no one knows how it really works” (@Stevie Kim, Vinitaly International)

Assistiamo in questi tempi ad un proliferare di iniziative dedicate allo sbarco delle imprese italiane sulle principali piattaforme di e-commerce cinesi, ma la conoscenza di chi sono i protagonisti, come funziona questo nuovo mercato, con quali regole e costi, e soprattutto, qual è il segreto per avere successo, è ancora molto limitata.

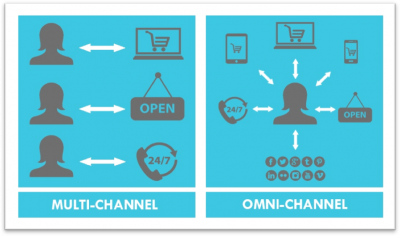

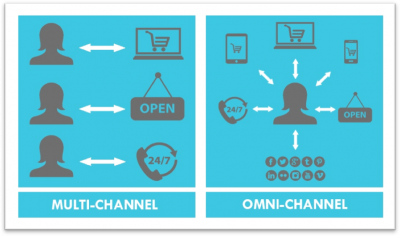

Omni-channel, cross-channel, online to offline (“O2O”) sono termini inflazionati, che vengono spesso usati a sproposito: per iniziare, dunque, di cosa stiamo parlando?

Secondo Wikipedia “Omnichannel is a cross-channel business model that companies use to increase customer experience (…) including channels such as physical locations, FAQ webpages, social media, live web chats, mobile applications and telephone communication. Companies that use omnichannel contend that a customer values the ability to be in constant contact with a company through multiple avenues at the same time”.

Possiamo sintetizzare dunque il concetto di omni-channel o cross channel come la creazione di un sistema di promozione e vendita dei prodotti attraverso diversi canali, tra loro integrati, con l’obiettivo di raggiungere il consumatore/cliente e di consentirgli un passaggio senza soluzione di continuità tra sito web aziendale, piattaforme di e-commerce specializzate su una certa tipologia di prodotti (c.d. “verticali”) o generaliste (“orizzontali”), punti vendita fisici, social media, campagne di marketing ed eventi di promozione tradizionali e/o digitali.

Omni-channel, dunque, non è un sinonimo di e-commerce ma descrive un sistema molto più complesso, che richiede una chiara strategia di comunicazione, promozione e vendita dei prodotti, che non può prescindere da un’azione integrata su vari canali, tra i quali è fondamentale quello “tradizionale” o fisico.

Aprire un virtual store o riuscire ad avere una presenza dei prodotti su Tmall o JD.com, senza aver elaborato una strategia omni-channel spesso comporta costi altissimi di start up e gestione, che l’impresa straniera non può sostenere nel medio termine, specie se le vendite dei prodotti, come spesso accade, fanno fatica a decollare.

Basti pensare, a questo proposito, che solo su Tmall Global sono presenti 14.500 brand stranieri, l’80% dei quali si affaccia per la prima volta al mercato cinese (fonte CBN Data and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd): la concorrenza è altissima e attrarre traffico e ottenere visibilità è molto costoso e richiede una grande esperienza di marketing sul mercato cinese.

Testimone del trend sempre più spinto Online to Offline è la recente acquisizione da parte di Alibaba Group Holding della catena di department stores Intime Retail Group Co. per 2,6 mld di dollari, operazione che fa seguito ad altri rilevanti investimenti nel settore della distribuzione tradizionale (Suning e Haier).

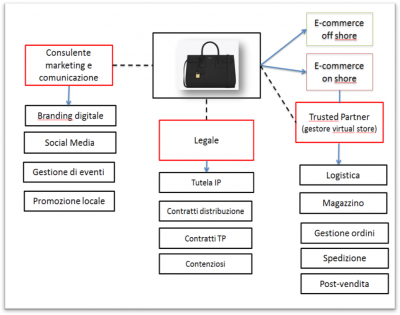

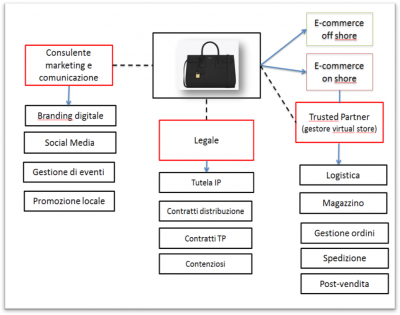

È imprescindibile, dunque, avere le idee chiare e una solida strategia, che si traduca in un business plan focalizzato sulla distribuzione omni-channel, messo a punto con consulenti esperti del mercato cinese nelle diverse aree di attività coinvolte: con un po’ di semplificazione il quadro potrebbe essere rappresentato così:

Gli aspetti da considerare sono molteplici: tutela del marchio, import dei prodotti, magazzino e logistica, accordi contrattuali con il gestore del virtual store e con i distributori online e offline, gestione dell’attività di promozione su internet e social media, customer care.

Tratteremo in una serie di articoli i punti principali per preparare in modo professionale e completo una strategia efficace di distribuzione omni-channel in Cina:

- Marchio, dominio web, account social media: la protezione della proprietà intellettuale

- L’import dei prodotti in Cina

- Come scegliere il distributore

- Adempimenti e costi di apertura e gestione di un virtual store

- Come si concilia la distribuzione tradizionale con quella e-commerce on shore e off shore

- Come negoziare e redigere un contratto di vendita e di distribuzione in Cina

- La normativa a tutela del consumatore

- La gestione dei contenziosi

Recently People’s Republic of China central government has unveiled and adopted a wide range of initiative to reduce the regulatory burden on daily business operations and provide greater autonomy in investment decision-making.

The reforms aim to give both domestic and foreign investors more autonomy and should make investments in the private sector much easier by reducing bureaucracy and increasing transparency. Investors will have more flexibility to determine the form, amount and timing of their business contributions. In addition, a system of publicly-available, electronic information (including annual filings and a corporate blacklist) will replace the old annual inspection system. Thanks to these reforms China’s requirements will become one step closer to international standards.

In this post I will analyze which are the enterprises affected by the reform; the Negative-list – setting out the industries that still need the approval to be established – and the new application process for company establishment.

Foreign invested enterprises

Generally speaking, foreign invested enterprises are the vehicle through which foreign investors may establish a presence to do business in China, choosing among one of the several different statutory forms recognized by the existing regulatory regime (such as: Wholly Foreign Owned Enterprise – WFOE; Equity Joint Venture – EJV; Contractual Joint Venture – CJV; Foreign Invested Company Limited by Shares; Foreign Invested Partnership Enterprise; or Holding companies). These entities are regulated under stricter laws than domestic companies, and are also subject to the same generally-applicable regulations.

The establishment of FIEs in Mainland China up is currently subject to a rather lengthy and bureaucratic examination and approval process by different Authorities. The same stringent requirements and burdensome procedure apply also to any major change related to FIEs structure, such as: increase or decrease of total investment/registered capital; change of business scope; shares or equity transfer; merger, division or dissolution; etc.

Nowadays, the set-up procedure of a WFOE undergoes through the following steps, having an average time frame of at least 3-4 months for the whole process:

Pre-issuance Business License

- Collection of the basic information from Investor’s side (7 working days)

- Company name pre-approval (5-7 working days)

- Lease agreement (it depends on Investor/Landlord)

- Legalized documents prepare by the Investor for the incorporation (few weeks)

- Certificate of Approval issued by MOFCOM (4 weeks)

- Business license issued by AIC (at least 10 working days)

Post-issuance Business License

- Carve company chops (1-2 working days)

- Foreign exchange registration certificate (around 10 working days)

- Open a CNY bank account (depends on the bank)

- Open a Foreign capital account (at least one week)

- Capital injection, in compliance with company Article of Association

- Capital verification report (it depends on accounting firm)

- Foreign trade operator filing before MOFCOM (at least 5 working days)

- Basic Customs Registration Certificate – if any (at least 5 working days)

- Advance Customs Registration (at least 30 working days)

- SAFE Preliminary Foreign Trader filing (2-3 working days)

- VAT general taxpayer application (1-2 working days)

- VAT general taxpayer invoice quota (30-60 working days)

On September 3rd 2016, the China National People Congress (NPC) Standing Committee adopted a resolution introducing several amendments related to the establishment of foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) in China, which has taken effect starting from October 1st 2016. The resolution is going to produce its effect for some of the FIEs statutory forms only (WFOE, EJV, CJV).

These amendments repeal the current examination and approval regime to set-up legal entities, shifting to a different system where a FIE may be established following a streamline procedure of filing requirements before the competent authority, as long as the industry in which it engages is not subject to any national market access restrictions.

Negative List

Within October 2016 a Negative List will be issued, setting out the industries in which FIE establishment must still be examined and approved under the existing laws and regulations: a complicated and time consuming process, involving verification, approval and registration with several Authorities. The current list includes:

- Agriculture and fishery (crop seed, animal husbandry, etc.)

- Infrastructure (airports, railroads, postal service, telecom and internet, etc.)

- Wholesale and retail (newspaper and magazine, tobacco, lottery, etc.)

- Finance (investment in banks or other financial companies, etc.)

- Professional services (accounting, legal advisors, market research, etc.)

- Education (establishment of schools, management of educational institution, etc.)

- Healthcare (EJV or CJV are required to set-up medical institution, etc.)

The publication of this list is a fundamental step, in order to better understand how the new regime will operate, as it will determine which sectors and matters are covered by the new filing requirements and, on the other hand, which items continue to undergo through a pre-approval process (basically all the sectors indicated in the Negative List).

The Negative List approach towards foreign investment was originally introduced by the Shanghai Free Trade Zone and subsequently extended to other Free Trade Zones in Mainland China (FTZs): according to the Negative List foreign investors were granted “national treatment” and were allowed to invest in several different business activities, with the exception of those listed in the Negative List form.

Essentially established as testing ground for new reforms, the FTZs were also established to drive regional growth by encouraging selected industries to cluster in specific geographical areas and, at the same time, served as a mean to promote experimental economic reforms and facilitate foreign direct investments.

New application process

In order to simplify bureaucracy cutting down time and costs, FTZs introduced a new application process for company establishment, the so called “one stop application procedure”. The applicant (foreign investor) may submit an online application through the relevant FTZs website, and then the business will be checked in order to verify whether it falls into the Negative List or not.

In case the requested business does not fall under the Negative list, all the application materials can be submitted and handled through one Authority (AIC – Administration for Industry and Commerce) within the Zone. All the relevant license and certificates (included but not limited to the business license, enterprise code certificate and tax registration certificate) will be issued altogether by AIC. In this way, the applicant can obtain all the relevant documents for company establishment in one place, contrasting with the outside Zone process where applicants must move between different authorities for the issuance of the different varieties of documents.

Thanks to the adopted amendments under the latest resolution (September 3rd 2016), this pilot scheme will apply also nationwide. The simplified filing requirement process will replaces the burdensome examination and approval procedure for the formation and change of key elements of FIEs, starting from October 1st 2016.

In the next post I will examine the main essential features of the new filing regime and the future perspectives following the reform.

Per descrivere le trattative precontrattuali in Cina è necessario spendere qualche parola sulle differenze culturali, sulle abilità da utilizzare durante la fase negoziale e sulle tecniche di redazione dei contratti.

Tutti questi 3 punti sono importanti quando si avvia una negoziazione con una controparte straniera, ma lo sono ancor di più quando si contratta con una controparte cinese.

In primis è fondamentale fare conoscenza con la cultura cinese prima di cominciare le trattative, specialmente se l’altro contraente (come spesso accade) non è molto esperto nel commercio internazionale e solo in poche occasioni ha negoziato con uomini d’affari o consulenti stranieri.

È bene aver presente che un businessman cinese si siederà al tavolo delle trattative solo dopo aver instaurato un rapporto personale con l’altro contraente, basato sulla fiducia ed il rispetto reciproco.

Chi crede che si possa giungere alla stipula di un contratto importante con una semplice viaggio di un paio di giorni in Cina o, ancor peggio, a distanza, è molto distante dalla realtà. Serviranno diversi incontri, diversi pranzi di lavoro e qualche drink per rompere il ghiaccio e preparare il terreno per i discorsi d’affari. È probabile, perciò, che siano necessari diversi viaggi in Cina per concludere l’affare: la fretta è sempre una cattiva consigliera e i cinesi sono negoziatori molto pazienti.

Nell’era di Internet può accadere che gli accordi siano conclusi a distanza, tramite lo scambio digitale di proposta e accettazione: ciò è raro con una controparte cinese, e non è un caso che molto spesso gli accordi così conclusi siano quelli più insidiosi, che spesso nascondono vere e proprie truffe.

Meglio, allora, prepararsi a lunghi negoziati e, anche se il contratto è concluso, non sovrastimarne il valore. Se nei paesi occidentali l’accordo scritto è visto come il punto d’arrivo dei negoziati, come una sorta di Bibbia del rapporto d’affari, in Cina i contratti sono considerati come non più di una tappa – seppur importante – del rapporto: spesso, infatti, il contratto viene visto più come una mera lettera d’intenti orientativa che come un accordo vincolante.

Accade frequentemente che la controparte cinese richieda cambiamenti dopo la firma del contratto, o semplicemente disapplichi gli accordi presi con tanta fatica, accampando le motivazioni più varie: occorre essere consapevoli di questo atteggiamento e farsi trovare pronti a richieste di rinegoziare l’accordo o – soluzione preferibile – inserire sin dall’inizio clausole e procedure per adattare il testo contrattuale alle frequenti modifiche che potrebbero essere necessarie.

Prima di sedersi finalmente al tavolo delle trattative è meglio essere sicuri che sia presente un traduttore affidabile: spesso la vostra controparte non parlerà in inglese e si affiderà completamente al traduttore, che potrebbe rovinare lo svolgimento della discussione nel caso in cui non padroneggiasse correttamente la terminologia necessaria.

Inoltre è fondamentale essere pazienti e non perdere mai il controllo: non bisogna dimenticare che mentre la tradizione del mondo occidentale è quella di procedere in maniera lineare nelle trattative, passando ordinatamente da una clausola all’altra, in Cina si adotta spesso un approccio olistico, discutendo sempre il contratto nella sua integrità: può allora capitare di trovarsi a ridiscutere clausole su cui si era già trovato un accordo il giorno prima, senza alcuna motivazione specifica.

Occorre tenere a mente, infine, che i negoziatori cinesi non amano il confronto diretto e in caso di disaccordo difficilmente prendono posizioni nette sulle questioni oggetto di discussione: spesso un sì in realtà significa no, e “ci devo pensare” quasi sicuramente equivale ad un futuro diniego.

La linea di fondo non è diversa da quella che dovrebbe orientare tutte le negoziazioni contrattuali: trovare un accordo bilanciato, che soddisfi gli interessi di tutte le parti; iniziare le trattative con una bozza di contratto chiaramente sbilanciata a vostro favore non solo complicherà il negoziato, ma potrebbe addirittura comprometterlo sul nascere.

A crucial clause in international contracts is the one which deals with litigation.

My advice, since we have seen that negotiation can be pretty long, complicated, and, exhausting, is that such clauses should not be the last to be dealt with, often times late at night when parties are exhausted, but the among the first.

Generally parties argue at length on such clauses, because neither party is willing to give up on its national jurisdiction for different reasons, foremost of all the fear that foreign judges would not be impartial and treat with favor the local part.

This deadlock often leads to bad compromises, like choosing the judge of a third state or combining the jurisdiction of one state with the application of the law of the other, which is definitely not recommended.

There is no one-fits-all solution to offer here: the advice is that such clauses should be tailor made on a case by case basis, and that the choice of a state court or arbitration should be expressed taking into account where the final decision shall be enforced.

If we foresee that our client may seek payment of a price or claim damages for breach of contract, ‘where is the money’ or ‘where are the assets’ should be the driving factor, and the choice of jurisdiction should be made accordingly.

If there is no such concern, and litigation may be foreseen only or mostly in a defensive scenario, then the proximity to the money or assets is no more a priority, and other options can be evaluated: in that case, the choice of a Judge in a far away country can be the best option, as it is a strong deterrent for litigation.

When battling for a clause with domestic jurisdiction, however, one should keep in mind that the process of recognition of a foreign decision is generally a rather complicated and lengthy process, even if (as is the case of Italy and China), there is a bilateral treaty for mutual recognition of judicial decisions (but very few cases have been recognized and enforced in China thereafter); it should also be kept in mind that all documents filed with the application for recognition of the foreign decision need to be translated into mandarin, notarized and legalized, which in complex litigations can represent an unforeseen additional high cost.

In other cases, like in the USA, where there is no bilateral treaty in this field, to litigate abroad often means that the foreign decision will be almost useless, with the necessity to sue again in China to seek enforcement of the decision.

Arbitration can be a valid alternative, as China is a member of the New York Convention of 1958 and enforcement of an arbitral award is in most cases easier and faster than the process of recognition of a foreign court decision.

I am frequently asked by my clients to revise sales contracts prepared by their actual or prospective Chinese counterparts.

I normally advise that it is much easier (and cheaper) to throw away the one they have received, which in most cases is a frankestein copy-pasted from different sources, drafted in poor English and with a Chinese version widely different from the English text, and to replace it with a good, new text, drafted by our law firm.

The first point which is important to know is that contracts can be drafted in a foreign language: they are perfectly valid in China even without a Chinese version, but a bilingual text is often expected and is definitely recommended.

Keeping in mind that the Contract one day can end up in a Chinese Court, where only Chinese is read and spoken, to foresee from the start that the Contract has a Chinese version, corresponding to the English one and using the right legal terminology, is a guarantee against misunderstandings, especially from the Judge himself.

That said, a common piece of advice is to keep the agreements simple and concise: we have seen how negotiations are usually long a can be a painful experience: you don’t want to start to discuss a contract with 15 pages of definitions, unless it is strictly necessary.

The best way to proceed is to prepare your own standard contract, have it translated into Chinese and have it reviewed by a Chinese lawyer, and then to propose it to the Chinese counterparts and work on that text.

The other way around, to work on a document prepared by the Chinese side, unless you are dealing with lawyers who have a good expertise of international trade and contracts, may be a bad idea, as it can usually be a frustrating and time consuming experience.

Last but not least: it is not sufficient to sign the contracts (possibly in every page): keep in mind that in order to be valid the contract needs to be stamped with the chop of the company, which is a uniquely carved piece of wood made by the local authorities.

To be on the safe side, it is better to have the contracts stamped: moreover, it is not a good sign if the person who signs the contract is not in possession of the chop, as this may mean that he is not the legal representative and has no power to bind the company.

CISG: it is applicable and you should not opt out.

The People’s Republic of China has ratified the Vienna Convention on the international sale of goods of 1980 (CISG) in the year 1986, with the result that the uniform law is an integral part of Chinese laws.

It is important to underline that China has made two reservations, under art. 1 (1) b and 11 of the CISG.

Under the first article, China refuses to apply the uniform law in cases where one of the parties is not resident in a contracting state, so indirect application is ruled out.

The second reservation is less substantial: China requires the written form for the validity of a contract of international sale of goods, while this is not required under domestic law (as Chinese Contract law of 1999 provides that contracts ‘may be made in written or in oral or any other form’).

It is never a good idea to enter into on oral agreement of international sale: in the specific case of China, this is even more true as the agreement could be voided.

We all know why it is important to apply the CISG and the reasons why it should not be ruled out, if possible: it is a common regulation of the parties’ obligations, which covers most of the important points of a sale contract and avoids the difficult task of choosing which law should apply to the sale agreement.

Another issue which is important mentioning when talking about international sales with China and CISG, is that, even though CISG is part of Chinese law, courts tend to apply it in a singular way.

Art. 142 of the General Principles of Civil Law of 1986 states that ‘the provisions of international treaties concluded or acceded by the PRC apply when they differ from the provisions of civil laws of the PRC’.

In most cases this leads to the application of Chinese law, because its provisions are often similar to the ones of CISG, or because national judges are not familiar with CISG.

In order to avoid this, parties have to indicate in the contract that they wish to apply ‘exclusively’ the CISG, otherwise the application of the uniform law might not be guaranteed.

Nell’era di internet e del commercio globale molti imprenditori italiani, e con loro i consulenti che li assistono, si trovano coinvolti, per la prima volta, in una trattativa con una controparte cinese. Come procedere?

1. Conoscere l’interlocutore

Essere certi che l’interlocutore sia chi afferma di essere è certamente un buon punto di partenza: le società cinesi si presentano infatti con una denominazione sociale in caratteri latini, che comprende la città in cui ha sede, un riferimento all’attività svolta e alla forma societaria (es: Beijing Great Wall Wines & Spirits co. LTD).

La denominazione societaria in questione, però, ha solo valenza commerciale e non è ufficiale: l’unica denominazione valida è quella in caratteri cinesi (di solito scritta su uno dei due lati del biglietto da visita) autorizzata dalla State Administration for Industry & Commerce (SAIC) al momento della costituzione della società.

La prima richiesta che è opportuno fare alla controparte è quindi di confermare la denominazione in caratteri cinesi e di trasmettere la business license della società, tramite la quale si può verificare che la società esista, quali sono sede e oggetto sociale, che la società sia attiva e il suo capitale registrato e versato.

Una accurata verifica della business license è anche utile per avere conferma che l’interlocutore sia credibile e abbia l’esperienza o la capacità organizzativa richieste per l’affare di cui si discute e per sgombrare subito il campo dal dubbio di avere a che fare con malintenzionati (che cercheranno pretesti per non fornire queste informazioni o interromperanno le comunicazioni: sul punto rimando al post Business con la Cina, occhio alle truffe on line).

La business license indica anche il nome del legale rappresentante, che è anche la persona che detiene il timbro della società, necessario al momento della firma dell’accordo: negoziare un contratto con chi è privo di potere di rappresentanza spesso si rivela una perdita di tempo e comporta comunque un allungamento dei tempi.

2. Definire i tempi del negoziato

La tempistica del negoziato con una controparte cinese si muove spesso in modo schizofrenico, tra massima urgenza e tempi biblici. Si alternando richieste di informazioni dettagliatissime sui prodotti o firma di accordi in tempi rapidissimi a riscontri dalla Cina con tempi eterni, per giustificare i quali si invocano vari pretesti: il capo è impegnato in un lungo viaggio di lavoro è il più classico.

Questa altalena tra pressioni quotidiane e latitanza senza riscontri è spiazzante per la parte italiana, da prima indotta a sperare di chiudere un importante accordo in tempi rapidi e poi abbandonata a sé stessa per molti mesi. In casi simili suggerisco di indicare un termine finale per la chiusura dell’accordo e avvisare che non ci sarà disponibilità alla trattativa decorso il termine, lasciando intendere che potrebbe esistere un altro interlocutore per il progetto.

Nel caso, purtroppo frequente, in cui la controparte sparisca, sulla frustrazione per il mancato affare dovrebbe prevalere il sollievo di avere evitato un partner inaffidabile e di certo non veramente interessato al rapporto commerciale che si era discusso.

3. Conoscere le regole del gioco

Il progetto di una Joint Venture o di un accordo commerciale o societario è frutto di molti incontri e discussioni tra le parti, che in alcuni casi giungono a definire in modo dettagliato il progetto prima di rivolgersi al consulente, che viene coinvolto solo in fase già avanzata delle trattative, con l’aspettativa – spesso irrealistica- di poter formalizzare gli accordi in tempi brevissimi.

E’ bene ricordare che la possibilità di realizzare investimenti diretti in Cina è regolamentata dalla legge cinese e che la controparte locale con la quale si tratta spesso non conosce quali sono le regole da rispettare da parte di un operatore straniero, come ad esempio le quote di partecipazione al capitale di una JV sino-straniera, i requisiti per l’accesso ai finanziamenti o i presupposti per la costruzione di una rete di franchising.

Il rischio è dunque di spendere molto tempo a costruire un progetto per poi scoprire che non è realizzabile nei termini immaginati dalle parti, con il rischio di veder sfumare l’affare: l’opinione di un esperto sulla fattibilità dell’operazione è consigliabile che venga acquisita sin da subito.

4. Procedere step by step

Il primo contatto commerciale è caratterizzato spesso da grande euforia da entrambe le parti, che vedono nella possibile collaborazione grandi opportunità di business per le rispettive società. La richiesta più frequente con la quale ci si confronta, in questi casi, è quella di costituire una Joint Venture in Cina, come veicolo per la produzione o commercializzazione dei prodotti o servizi stranieri.

Un consiglio utile, in questi casi, è quello di cercare di fare la massima chiarezza possibile sui rispettivi obiettivi: la Joint Venture sino-straniera non è l’unico modo di accede al mercato cinese, richiede investimenti finanziari e di risorse umane importanti e presenta complessità di gestione della società molto elevate. Storicamente, sono molti di più i casi i casi in cui la JV sino-italiana fallisce che non quelli in cui l’impresa ha successo.

Meglio dunque iniziare il rapporto con forme di collaborazione più snelle, come la concessione di vendita, la distribuzione commerciale o la licenza di produzione, che consentono di testare sul campo la controparte per un certo periodo e di avere conferma della sua effettiva dedizione al rapporto e dei riscontri del mercato.

5. Memorandum of Understanding

Uno strumento per fare chiarezza sugli obiettivi che le parti si propongono di ottenere e sui tempi e modi del negoziato è quello di concludere un accordo preliminare, generalmente definito Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) o Letter of Intent (LoI), nel quale si traccia una road map delle future trattative, impegnandosi a negoziare in buona fede un certo progetto, del quale si indicano le linee generali.

Le opinioni al proposito sono le più diverse: c’è chi ritiene che si tratti di una perdita di tempo bella e buona, visto che il documento generalmente non ha effetti vincolanti e preferisce saltare a piè pari questo passaggio; in altri casi le parti confessano candidamente di non avere nemmeno letto quello che avevano firmato, visto che la vera trattativa si sarebbe fatta solo al momento di parlare dell’accordo societario; altri ancora pretendono di negoziare questo contratto nei minimi dettaglicome se si trattasse già di un accordo definitivo, con obbligazioni contrattuali vincolanti e addirittura indicazione delle penali che si applicheranno in caso di inadempimento al futuro contratto.

Un MoU, a mio avviso, è molto utile e dovrebbe essere sempre il primo step del negoziato. A condizione, però, che venga utilizzato in modo corretto, ossia che si tratti di un accordo semplice che riporti le premesse della collaborazione (chi sono le parti e e cosa fanno), le intenzioni delle parti (perché interessa collaborare), gli obiettivi che si intendono raggiungere, il tipo di accordo che si vuole concludere, i tempi del negoziato, l’impegno alla riservatezza e gli eventuali punti chiave del futuro contratto sui quali esiste già un consenso di massima: sarà un punto di riferimento importante nel futuro negoziato, al quale richiamarsi per tenere la trattativa sui giusti binari.

Scrivi a China – Know your investor

China – WOFE set up process

10 Ottobre 2016

-

Cina

- Diritto societario

Chinese outbound M&A was one of the main topics of interest at the 2017 Hong Kong IFLR Forum on M&A in Asia, a great event with an outstanding level of speakers and very interesting discussions on various themes related to international investments.

All the attendants shared the view that momentum for Chinese overseas investments is still strong, despite the recent policy aiming at curbing the outflow of capitals from China.

A particularly interesting session was that on “best practices to overcome credibility and experience gaps increasingly faced by “off the radar” Chinese bidders”.

Opening a one-to-one negotiation or letting a Chinese company bid at an auction involves often great deal of uncertainty, as most participants to the session shared the experience of having seeing their Chinese counterpart walk away from the negotiation without any explanation (the so-called “Random Investors”).

I have scribbled down the take-aways of the discussion as follows.

Main clues to spot early on the Random investor:

- the Company pops out from nowhere and has no track record of overseas investments;

- the Company has no legal or financial advisors, or if they do, their advisors are not experienced in overseas transactions;

- the Company has excellent advisors… but has not paid their fees (yes, that happens)

- the target does not belong to the Company’s core business (and there is no explanation for their interest for the deal);

What should you do to be on the safe side?

- request a written declaration of interest, expressing the reasons why the Company wants to invest in the target and what is their mid term strategy, signed and stamped by the legal representative (if they are not ready to hand over this letter the game can stop here).

- If the Company represents a group of investors, require full disclosure and letters of confirmation from all parties, from day one (AC Milan’s case is a good example of what happens later on if there is no disclosure of all players, and their stakes in the deal);

- request proof that the Company has filed the application for the authorisation to invest overseas (due to the recent tightening of controls on capital outflow, this step is fundamental);

- request proof that they have the finance needed for the deal (either onshore or, better, off-shore);

- make clear that you will require a “break fee” (which can vary from 5 to 10%) in case they walk away from the negotiation (we have heard of US companies expecting 30 to 50% break fee on the value of the deal…)

“E-commerce and omni-channel distribution in China: everyone talks about it, no one knows how it really works” (@Stevie Kim, Vinitaly International)

Assistiamo in questi tempi ad un proliferare di iniziative dedicate allo sbarco delle imprese italiane sulle principali piattaforme di e-commerce cinesi, ma la conoscenza di chi sono i protagonisti, come funziona questo nuovo mercato, con quali regole e costi, e soprattutto, qual è il segreto per avere successo, è ancora molto limitata.

Omni-channel, cross-channel, online to offline (“O2O”) sono termini inflazionati, che vengono spesso usati a sproposito: per iniziare, dunque, di cosa stiamo parlando?

Secondo Wikipedia “Omnichannel is a cross-channel business model that companies use to increase customer experience (…) including channels such as physical locations, FAQ webpages, social media, live web chats, mobile applications and telephone communication. Companies that use omnichannel contend that a customer values the ability to be in constant contact with a company through multiple avenues at the same time”.

Possiamo sintetizzare dunque il concetto di omni-channel o cross channel come la creazione di un sistema di promozione e vendita dei prodotti attraverso diversi canali, tra loro integrati, con l’obiettivo di raggiungere il consumatore/cliente e di consentirgli un passaggio senza soluzione di continuità tra sito web aziendale, piattaforme di e-commerce specializzate su una certa tipologia di prodotti (c.d. “verticali”) o generaliste (“orizzontali”), punti vendita fisici, social media, campagne di marketing ed eventi di promozione tradizionali e/o digitali.

Omni-channel, dunque, non è un sinonimo di e-commerce ma descrive un sistema molto più complesso, che richiede una chiara strategia di comunicazione, promozione e vendita dei prodotti, che non può prescindere da un’azione integrata su vari canali, tra i quali è fondamentale quello “tradizionale” o fisico.

Aprire un virtual store o riuscire ad avere una presenza dei prodotti su Tmall o JD.com, senza aver elaborato una strategia omni-channel spesso comporta costi altissimi di start up e gestione, che l’impresa straniera non può sostenere nel medio termine, specie se le vendite dei prodotti, come spesso accade, fanno fatica a decollare.

Basti pensare, a questo proposito, che solo su Tmall Global sono presenti 14.500 brand stranieri, l’80% dei quali si affaccia per la prima volta al mercato cinese (fonte CBN Data and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd): la concorrenza è altissima e attrarre traffico e ottenere visibilità è molto costoso e richiede una grande esperienza di marketing sul mercato cinese.

Testimone del trend sempre più spinto Online to Offline è la recente acquisizione da parte di Alibaba Group Holding della catena di department stores Intime Retail Group Co. per 2,6 mld di dollari, operazione che fa seguito ad altri rilevanti investimenti nel settore della distribuzione tradizionale (Suning e Haier).

È imprescindibile, dunque, avere le idee chiare e una solida strategia, che si traduca in un business plan focalizzato sulla distribuzione omni-channel, messo a punto con consulenti esperti del mercato cinese nelle diverse aree di attività coinvolte: con un po’ di semplificazione il quadro potrebbe essere rappresentato così:

Gli aspetti da considerare sono molteplici: tutela del marchio, import dei prodotti, magazzino e logistica, accordi contrattuali con il gestore del virtual store e con i distributori online e offline, gestione dell’attività di promozione su internet e social media, customer care.

Tratteremo in una serie di articoli i punti principali per preparare in modo professionale e completo una strategia efficace di distribuzione omni-channel in Cina:

- Marchio, dominio web, account social media: la protezione della proprietà intellettuale

- L’import dei prodotti in Cina

- Come scegliere il distributore

- Adempimenti e costi di apertura e gestione di un virtual store

- Come si concilia la distribuzione tradizionale con quella e-commerce on shore e off shore

- Come negoziare e redigere un contratto di vendita e di distribuzione in Cina

- La normativa a tutela del consumatore

- La gestione dei contenziosi

Recently People’s Republic of China central government has unveiled and adopted a wide range of initiative to reduce the regulatory burden on daily business operations and provide greater autonomy in investment decision-making.

The reforms aim to give both domestic and foreign investors more autonomy and should make investments in the private sector much easier by reducing bureaucracy and increasing transparency. Investors will have more flexibility to determine the form, amount and timing of their business contributions. In addition, a system of publicly-available, electronic information (including annual filings and a corporate blacklist) will replace the old annual inspection system. Thanks to these reforms China’s requirements will become one step closer to international standards.

In this post I will analyze which are the enterprises affected by the reform; the Negative-list – setting out the industries that still need the approval to be established – and the new application process for company establishment.

Foreign invested enterprises

Generally speaking, foreign invested enterprises are the vehicle through which foreign investors may establish a presence to do business in China, choosing among one of the several different statutory forms recognized by the existing regulatory regime (such as: Wholly Foreign Owned Enterprise – WFOE; Equity Joint Venture – EJV; Contractual Joint Venture – CJV; Foreign Invested Company Limited by Shares; Foreign Invested Partnership Enterprise; or Holding companies). These entities are regulated under stricter laws than domestic companies, and are also subject to the same generally-applicable regulations.

The establishment of FIEs in Mainland China up is currently subject to a rather lengthy and bureaucratic examination and approval process by different Authorities. The same stringent requirements and burdensome procedure apply also to any major change related to FIEs structure, such as: increase or decrease of total investment/registered capital; change of business scope; shares or equity transfer; merger, division or dissolution; etc.

Nowadays, the set-up procedure of a WFOE undergoes through the following steps, having an average time frame of at least 3-4 months for the whole process:

Pre-issuance Business License

- Collection of the basic information from Investor’s side (7 working days)

- Company name pre-approval (5-7 working days)

- Lease agreement (it depends on Investor/Landlord)

- Legalized documents prepare by the Investor for the incorporation (few weeks)

- Certificate of Approval issued by MOFCOM (4 weeks)

- Business license issued by AIC (at least 10 working days)

Post-issuance Business License

- Carve company chops (1-2 working days)

- Foreign exchange registration certificate (around 10 working days)

- Open a CNY bank account (depends on the bank)

- Open a Foreign capital account (at least one week)

- Capital injection, in compliance with company Article of Association

- Capital verification report (it depends on accounting firm)

- Foreign trade operator filing before MOFCOM (at least 5 working days)

- Basic Customs Registration Certificate – if any (at least 5 working days)

- Advance Customs Registration (at least 30 working days)

- SAFE Preliminary Foreign Trader filing (2-3 working days)

- VAT general taxpayer application (1-2 working days)

- VAT general taxpayer invoice quota (30-60 working days)

On September 3rd 2016, the China National People Congress (NPC) Standing Committee adopted a resolution introducing several amendments related to the establishment of foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) in China, which has taken effect starting from October 1st 2016. The resolution is going to produce its effect for some of the FIEs statutory forms only (WFOE, EJV, CJV).

These amendments repeal the current examination and approval regime to set-up legal entities, shifting to a different system where a FIE may be established following a streamline procedure of filing requirements before the competent authority, as long as the industry in which it engages is not subject to any national market access restrictions.

Negative List

Within October 2016 a Negative List will be issued, setting out the industries in which FIE establishment must still be examined and approved under the existing laws and regulations: a complicated and time consuming process, involving verification, approval and registration with several Authorities. The current list includes:

- Agriculture and fishery (crop seed, animal husbandry, etc.)

- Infrastructure (airports, railroads, postal service, telecom and internet, etc.)

- Wholesale and retail (newspaper and magazine, tobacco, lottery, etc.)

- Finance (investment in banks or other financial companies, etc.)

- Professional services (accounting, legal advisors, market research, etc.)

- Education (establishment of schools, management of educational institution, etc.)

- Healthcare (EJV or CJV are required to set-up medical institution, etc.)

The publication of this list is a fundamental step, in order to better understand how the new regime will operate, as it will determine which sectors and matters are covered by the new filing requirements and, on the other hand, which items continue to undergo through a pre-approval process (basically all the sectors indicated in the Negative List).

The Negative List approach towards foreign investment was originally introduced by the Shanghai Free Trade Zone and subsequently extended to other Free Trade Zones in Mainland China (FTZs): according to the Negative List foreign investors were granted “national treatment” and were allowed to invest in several different business activities, with the exception of those listed in the Negative List form.

Essentially established as testing ground for new reforms, the FTZs were also established to drive regional growth by encouraging selected industries to cluster in specific geographical areas and, at the same time, served as a mean to promote experimental economic reforms and facilitate foreign direct investments.

New application process

In order to simplify bureaucracy cutting down time and costs, FTZs introduced a new application process for company establishment, the so called “one stop application procedure”. The applicant (foreign investor) may submit an online application through the relevant FTZs website, and then the business will be checked in order to verify whether it falls into the Negative List or not.

In case the requested business does not fall under the Negative list, all the application materials can be submitted and handled through one Authority (AIC – Administration for Industry and Commerce) within the Zone. All the relevant license and certificates (included but not limited to the business license, enterprise code certificate and tax registration certificate) will be issued altogether by AIC. In this way, the applicant can obtain all the relevant documents for company establishment in one place, contrasting with the outside Zone process where applicants must move between different authorities for the issuance of the different varieties of documents.

Thanks to the adopted amendments under the latest resolution (September 3rd 2016), this pilot scheme will apply also nationwide. The simplified filing requirement process will replaces the burdensome examination and approval procedure for the formation and change of key elements of FIEs, starting from October 1st 2016.

In the next post I will examine the main essential features of the new filing regime and the future perspectives following the reform.

Per descrivere le trattative precontrattuali in Cina è necessario spendere qualche parola sulle differenze culturali, sulle abilità da utilizzare durante la fase negoziale e sulle tecniche di redazione dei contratti.

Tutti questi 3 punti sono importanti quando si avvia una negoziazione con una controparte straniera, ma lo sono ancor di più quando si contratta con una controparte cinese.

In primis è fondamentale fare conoscenza con la cultura cinese prima di cominciare le trattative, specialmente se l’altro contraente (come spesso accade) non è molto esperto nel commercio internazionale e solo in poche occasioni ha negoziato con uomini d’affari o consulenti stranieri.

È bene aver presente che un businessman cinese si siederà al tavolo delle trattative solo dopo aver instaurato un rapporto personale con l’altro contraente, basato sulla fiducia ed il rispetto reciproco.

Chi crede che si possa giungere alla stipula di un contratto importante con una semplice viaggio di un paio di giorni in Cina o, ancor peggio, a distanza, è molto distante dalla realtà. Serviranno diversi incontri, diversi pranzi di lavoro e qualche drink per rompere il ghiaccio e preparare il terreno per i discorsi d’affari. È probabile, perciò, che siano necessari diversi viaggi in Cina per concludere l’affare: la fretta è sempre una cattiva consigliera e i cinesi sono negoziatori molto pazienti.

Nell’era di Internet può accadere che gli accordi siano conclusi a distanza, tramite lo scambio digitale di proposta e accettazione: ciò è raro con una controparte cinese, e non è un caso che molto spesso gli accordi così conclusi siano quelli più insidiosi, che spesso nascondono vere e proprie truffe.

Meglio, allora, prepararsi a lunghi negoziati e, anche se il contratto è concluso, non sovrastimarne il valore. Se nei paesi occidentali l’accordo scritto è visto come il punto d’arrivo dei negoziati, come una sorta di Bibbia del rapporto d’affari, in Cina i contratti sono considerati come non più di una tappa – seppur importante – del rapporto: spesso, infatti, il contratto viene visto più come una mera lettera d’intenti orientativa che come un accordo vincolante.

Accade frequentemente che la controparte cinese richieda cambiamenti dopo la firma del contratto, o semplicemente disapplichi gli accordi presi con tanta fatica, accampando le motivazioni più varie: occorre essere consapevoli di questo atteggiamento e farsi trovare pronti a richieste di rinegoziare l’accordo o – soluzione preferibile – inserire sin dall’inizio clausole e procedure per adattare il testo contrattuale alle frequenti modifiche che potrebbero essere necessarie.

Prima di sedersi finalmente al tavolo delle trattative è meglio essere sicuri che sia presente un traduttore affidabile: spesso la vostra controparte non parlerà in inglese e si affiderà completamente al traduttore, che potrebbe rovinare lo svolgimento della discussione nel caso in cui non padroneggiasse correttamente la terminologia necessaria.

Inoltre è fondamentale essere pazienti e non perdere mai il controllo: non bisogna dimenticare che mentre la tradizione del mondo occidentale è quella di procedere in maniera lineare nelle trattative, passando ordinatamente da una clausola all’altra, in Cina si adotta spesso un approccio olistico, discutendo sempre il contratto nella sua integrità: può allora capitare di trovarsi a ridiscutere clausole su cui si era già trovato un accordo il giorno prima, senza alcuna motivazione specifica.

Occorre tenere a mente, infine, che i negoziatori cinesi non amano il confronto diretto e in caso di disaccordo difficilmente prendono posizioni nette sulle questioni oggetto di discussione: spesso un sì in realtà significa no, e “ci devo pensare” quasi sicuramente equivale ad un futuro diniego.

La linea di fondo non è diversa da quella che dovrebbe orientare tutte le negoziazioni contrattuali: trovare un accordo bilanciato, che soddisfi gli interessi di tutte le parti; iniziare le trattative con una bozza di contratto chiaramente sbilanciata a vostro favore non solo complicherà il negoziato, ma potrebbe addirittura comprometterlo sul nascere.

A crucial clause in international contracts is the one which deals with litigation.

My advice, since we have seen that negotiation can be pretty long, complicated, and, exhausting, is that such clauses should not be the last to be dealt with, often times late at night when parties are exhausted, but the among the first.

Generally parties argue at length on such clauses, because neither party is willing to give up on its national jurisdiction for different reasons, foremost of all the fear that foreign judges would not be impartial and treat with favor the local part.

This deadlock often leads to bad compromises, like choosing the judge of a third state or combining the jurisdiction of one state with the application of the law of the other, which is definitely not recommended.

There is no one-fits-all solution to offer here: the advice is that such clauses should be tailor made on a case by case basis, and that the choice of a state court or arbitration should be expressed taking into account where the final decision shall be enforced.

If we foresee that our client may seek payment of a price or claim damages for breach of contract, ‘where is the money’ or ‘where are the assets’ should be the driving factor, and the choice of jurisdiction should be made accordingly.

If there is no such concern, and litigation may be foreseen only or mostly in a defensive scenario, then the proximity to the money or assets is no more a priority, and other options can be evaluated: in that case, the choice of a Judge in a far away country can be the best option, as it is a strong deterrent for litigation.

When battling for a clause with domestic jurisdiction, however, one should keep in mind that the process of recognition of a foreign decision is generally a rather complicated and lengthy process, even if (as is the case of Italy and China), there is a bilateral treaty for mutual recognition of judicial decisions (but very few cases have been recognized and enforced in China thereafter); it should also be kept in mind that all documents filed with the application for recognition of the foreign decision need to be translated into mandarin, notarized and legalized, which in complex litigations can represent an unforeseen additional high cost.

In other cases, like in the USA, where there is no bilateral treaty in this field, to litigate abroad often means that the foreign decision will be almost useless, with the necessity to sue again in China to seek enforcement of the decision.

Arbitration can be a valid alternative, as China is a member of the New York Convention of 1958 and enforcement of an arbitral award is in most cases easier and faster than the process of recognition of a foreign court decision.

I am frequently asked by my clients to revise sales contracts prepared by their actual or prospective Chinese counterparts.

I normally advise that it is much easier (and cheaper) to throw away the one they have received, which in most cases is a frankestein copy-pasted from different sources, drafted in poor English and with a Chinese version widely different from the English text, and to replace it with a good, new text, drafted by our law firm.

The first point which is important to know is that contracts can be drafted in a foreign language: they are perfectly valid in China even without a Chinese version, but a bilingual text is often expected and is definitely recommended.

Keeping in mind that the Contract one day can end up in a Chinese Court, where only Chinese is read and spoken, to foresee from the start that the Contract has a Chinese version, corresponding to the English one and using the right legal terminology, is a guarantee against misunderstandings, especially from the Judge himself.

That said, a common piece of advice is to keep the agreements simple and concise: we have seen how negotiations are usually long a can be a painful experience: you don’t want to start to discuss a contract with 15 pages of definitions, unless it is strictly necessary.

The best way to proceed is to prepare your own standard contract, have it translated into Chinese and have it reviewed by a Chinese lawyer, and then to propose it to the Chinese counterparts and work on that text.

The other way around, to work on a document prepared by the Chinese side, unless you are dealing with lawyers who have a good expertise of international trade and contracts, may be a bad idea, as it can usually be a frustrating and time consuming experience.

Last but not least: it is not sufficient to sign the contracts (possibly in every page): keep in mind that in order to be valid the contract needs to be stamped with the chop of the company, which is a uniquely carved piece of wood made by the local authorities.

To be on the safe side, it is better to have the contracts stamped: moreover, it is not a good sign if the person who signs the contract is not in possession of the chop, as this may mean that he is not the legal representative and has no power to bind the company.

CISG: it is applicable and you should not opt out.

The People’s Republic of China has ratified the Vienna Convention on the international sale of goods of 1980 (CISG) in the year 1986, with the result that the uniform law is an integral part of Chinese laws.

It is important to underline that China has made two reservations, under art. 1 (1) b and 11 of the CISG.

Under the first article, China refuses to apply the uniform law in cases where one of the parties is not resident in a contracting state, so indirect application is ruled out.

The second reservation is less substantial: China requires the written form for the validity of a contract of international sale of goods, while this is not required under domestic law (as Chinese Contract law of 1999 provides that contracts ‘may be made in written or in oral or any other form’).

It is never a good idea to enter into on oral agreement of international sale: in the specific case of China, this is even more true as the agreement could be voided.

We all know why it is important to apply the CISG and the reasons why it should not be ruled out, if possible: it is a common regulation of the parties’ obligations, which covers most of the important points of a sale contract and avoids the difficult task of choosing which law should apply to the sale agreement.

Another issue which is important mentioning when talking about international sales with China and CISG, is that, even though CISG is part of Chinese law, courts tend to apply it in a singular way.

Art. 142 of the General Principles of Civil Law of 1986 states that ‘the provisions of international treaties concluded or acceded by the PRC apply when they differ from the provisions of civil laws of the PRC’.

In most cases this leads to the application of Chinese law, because its provisions are often similar to the ones of CISG, or because national judges are not familiar with CISG.

In order to avoid this, parties have to indicate in the contract that they wish to apply ‘exclusively’ the CISG, otherwise the application of the uniform law might not be guaranteed.

Nell’era di internet e del commercio globale molti imprenditori italiani, e con loro i consulenti che li assistono, si trovano coinvolti, per la prima volta, in una trattativa con una controparte cinese. Come procedere?

1. Conoscere l’interlocutore

Essere certi che l’interlocutore sia chi afferma di essere è certamente un buon punto di partenza: le società cinesi si presentano infatti con una denominazione sociale in caratteri latini, che comprende la città in cui ha sede, un riferimento all’attività svolta e alla forma societaria (es: Beijing Great Wall Wines & Spirits co. LTD).

La denominazione societaria in questione, però, ha solo valenza commerciale e non è ufficiale: l’unica denominazione valida è quella in caratteri cinesi (di solito scritta su uno dei due lati del biglietto da visita) autorizzata dalla State Administration for Industry & Commerce (SAIC) al momento della costituzione della società.

La prima richiesta che è opportuno fare alla controparte è quindi di confermare la denominazione in caratteri cinesi e di trasmettere la business license della società, tramite la quale si può verificare che la società esista, quali sono sede e oggetto sociale, che la società sia attiva e il suo capitale registrato e versato.

Una accurata verifica della business license è anche utile per avere conferma che l’interlocutore sia credibile e abbia l’esperienza o la capacità organizzativa richieste per l’affare di cui si discute e per sgombrare subito il campo dal dubbio di avere a che fare con malintenzionati (che cercheranno pretesti per non fornire queste informazioni o interromperanno le comunicazioni: sul punto rimando al post Business con la Cina, occhio alle truffe on line).

La business license indica anche il nome del legale rappresentante, che è anche la persona che detiene il timbro della società, necessario al momento della firma dell’accordo: negoziare un contratto con chi è privo di potere di rappresentanza spesso si rivela una perdita di tempo e comporta comunque un allungamento dei tempi.

2. Definire i tempi del negoziato

La tempistica del negoziato con una controparte cinese si muove spesso in modo schizofrenico, tra massima urgenza e tempi biblici. Si alternando richieste di informazioni dettagliatissime sui prodotti o firma di accordi in tempi rapidissimi a riscontri dalla Cina con tempi eterni, per giustificare i quali si invocano vari pretesti: il capo è impegnato in un lungo viaggio di lavoro è il più classico.

Questa altalena tra pressioni quotidiane e latitanza senza riscontri è spiazzante per la parte italiana, da prima indotta a sperare di chiudere un importante accordo in tempi rapidi e poi abbandonata a sé stessa per molti mesi. In casi simili suggerisco di indicare un termine finale per la chiusura dell’accordo e avvisare che non ci sarà disponibilità alla trattativa decorso il termine, lasciando intendere che potrebbe esistere un altro interlocutore per il progetto.

Nel caso, purtroppo frequente, in cui la controparte sparisca, sulla frustrazione per il mancato affare dovrebbe prevalere il sollievo di avere evitato un partner inaffidabile e di certo non veramente interessato al rapporto commerciale che si era discusso.

3. Conoscere le regole del gioco

Il progetto di una Joint Venture o di un accordo commerciale o societario è frutto di molti incontri e discussioni tra le parti, che in alcuni casi giungono a definire in modo dettagliato il progetto prima di rivolgersi al consulente, che viene coinvolto solo in fase già avanzata delle trattative, con l’aspettativa – spesso irrealistica- di poter formalizzare gli accordi in tempi brevissimi.

E’ bene ricordare che la possibilità di realizzare investimenti diretti in Cina è regolamentata dalla legge cinese e che la controparte locale con la quale si tratta spesso non conosce quali sono le regole da rispettare da parte di un operatore straniero, come ad esempio le quote di partecipazione al capitale di una JV sino-straniera, i requisiti per l’accesso ai finanziamenti o i presupposti per la costruzione di una rete di franchising.

Il rischio è dunque di spendere molto tempo a costruire un progetto per poi scoprire che non è realizzabile nei termini immaginati dalle parti, con il rischio di veder sfumare l’affare: l’opinione di un esperto sulla fattibilità dell’operazione è consigliabile che venga acquisita sin da subito.

4. Procedere step by step

Il primo contatto commerciale è caratterizzato spesso da grande euforia da entrambe le parti, che vedono nella possibile collaborazione grandi opportunità di business per le rispettive società. La richiesta più frequente con la quale ci si confronta, in questi casi, è quella di costituire una Joint Venture in Cina, come veicolo per la produzione o commercializzazione dei prodotti o servizi stranieri.

Un consiglio utile, in questi casi, è quello di cercare di fare la massima chiarezza possibile sui rispettivi obiettivi: la Joint Venture sino-straniera non è l’unico modo di accede al mercato cinese, richiede investimenti finanziari e di risorse umane importanti e presenta complessità di gestione della società molto elevate. Storicamente, sono molti di più i casi i casi in cui la JV sino-italiana fallisce che non quelli in cui l’impresa ha successo.

Meglio dunque iniziare il rapporto con forme di collaborazione più snelle, come la concessione di vendita, la distribuzione commerciale o la licenza di produzione, che consentono di testare sul campo la controparte per un certo periodo e di avere conferma della sua effettiva dedizione al rapporto e dei riscontri del mercato.

5. Memorandum of Understanding

Uno strumento per fare chiarezza sugli obiettivi che le parti si propongono di ottenere e sui tempi e modi del negoziato è quello di concludere un accordo preliminare, generalmente definito Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) o Letter of Intent (LoI), nel quale si traccia una road map delle future trattative, impegnandosi a negoziare in buona fede un certo progetto, del quale si indicano le linee generali.

Le opinioni al proposito sono le più diverse: c’è chi ritiene che si tratti di una perdita di tempo bella e buona, visto che il documento generalmente non ha effetti vincolanti e preferisce saltare a piè pari questo passaggio; in altri casi le parti confessano candidamente di non avere nemmeno letto quello che avevano firmato, visto che la vera trattativa si sarebbe fatta solo al momento di parlare dell’accordo societario; altri ancora pretendono di negoziare questo contratto nei minimi dettaglicome se si trattasse già di un accordo definitivo, con obbligazioni contrattuali vincolanti e addirittura indicazione delle penali che si applicheranno in caso di inadempimento al futuro contratto.

Un MoU, a mio avviso, è molto utile e dovrebbe essere sempre il primo step del negoziato. A condizione, però, che venga utilizzato in modo corretto, ossia che si tratti di un accordo semplice che riporti le premesse della collaborazione (chi sono le parti e e cosa fanno), le intenzioni delle parti (perché interessa collaborare), gli obiettivi che si intendono raggiungere, il tipo di accordo che si vuole concludere, i tempi del negoziato, l’impegno alla riservatezza e gli eventuali punti chiave del futuro contratto sui quali esiste già un consenso di massima: sarà un punto di riferimento importante nel futuro negoziato, al quale richiamarsi per tenere la trattativa sui giusti binari.