-

Europa

-

Germania

Distribuzione digitale

4 Aprile 2019

- Distribuzione

Con la recentissima pronuncia del 2 maggio 2019 (causa C-614/17), la Corte di Giustizia UE ha stabilito che la normativa europea in tema di protezione delle indicazioni geografiche e delle denominazioni d’origine dei prodotti agricoli ed alimentari deve essere interpretata nel senso che «l’utilizzo di segni figurativi che evocano l’area geografica alla quale è collegata una denominazione d’origine […] può costituire un’evocazione [vietata dalla normativa europea, n.d.r.] della medesima anche nel caso in cui i suddetti segni figurativi siano utilizzati da un produttore stabilito in tale regione, ma i cui prodotti, simili o comparabili a quelli protetti da tale denominazione d’origine, non sono protetti da quest’ultima».

Questa sentenza, che prende spunto dal curioso caso dei formaggi de La Mancha, rappresenta una pietra miliare per la tutela delle eccellenze enogastronomiche nazionali, con importanti risvolti sui prodotti «Made in Italy».

Il caso

Il caso trae origine dalla commercializzazione, da parte dell’Industrial Quesera Cuquerella SL [«IQC»], di alcuni formaggi attraverso l’utilizzo di etichette evocative del noto personaggio di Miguel de Cervantes, ossia Don Chisciotte de La Mancha.

Nella sostanza, si trattava di etichette contenenti raffigurazioni tradizionali di Don Chisciotte, di un cavallo magro evocativo del cavallo «Ronzinante» e di paesaggi con mulini a vento, per commercializzare i formaggi «Super Rocinante», «Rocinante» e «Adarga de Oro» [il termine «adarga» rappresenta un arcaismo spagnolo, utilizzato da Miguel de Cervantes per indicare lo scudo di Don Chisciotte, n.d.r.], non compresi, però, all’interno del DOP «queso manchego» [formaggio de La Mancha, in spagnolo, n.d.r.].

Per tale ragione, la Fondazione Queso Manchego [«FQM»], incaricata della gestione e della protezione della DOP «queso manchego», si rivolgeva al giudice spagnolo, affinché dichiarasse che tale utilizzo, riguardando formaggi non compresi nella DOP, rappresentava una violazione della normativa europea in tema di protezione delle indicazioni geografiche e delle denominazioni d’origine dei prodotti agricoli ed alimentari di cui al Regolamento U.E. 510/2016.

La decisione dei giudici spagnoli ed il rinvio del Tribunal Supremo

Tanto in primo che poi in secondo grado, i giudici spagnoli rigettavano la richiesta della FQM, ritenendo che l’utilizzo di immagini evocative de La Mancha per commercializzare formaggi non protetti dalla DOP «queso manchego», fosse in grado di indurre il consumatore a pensare, appunto, alla regione spagnola, ma non necessariamente alla DOP «queso manchego».

FQM si rivolgeva, quindi, al Tribunal Supremo spagnolo, che rinviava la questione alla Corte di Giustizia UE, ritenendo necessario, per risolvere il caso concreto, sapere come debba essere interpretata la normativa europea ed osservando che:

- il termine «manchego» in spagnolo qualifica ciò che è originario de La Mancha e che la DOP «queso manchego» protegge i formaggi di pecora provenienti da tale regione e prodotti rispettando quanto previsto nel relativo disciplinare;

- i nomi e le immagini utilizzate da IQC per commercializzare i propri formaggi, non protetti dalla DOP «queso manchego», richiamano Don Chisciotte e La Mancha, a cui tale personaggio è tradizionalmente associato.

La decisione della Corte di Giustizia UE

Con la sentenza del 02 maggio 2019, la Corte di Giustizia UE risponde ai quesiti posti dal Tribunal Supremo spagnolo.

- I segni figurativi sono in grado di ingenerare confusione nel consumatore?

Il Tribunal Supremo spagnolo chiede alla Corte UE di chiarire se l’uso di segni figurativi per evocare una DOP è in grado di per sé di ingenerare confusione nel consumatore.

La Corte, tenendo conto della volontà del legislatore UE di dare ampia protezione alle DOP, ha dato una risposta affermativa alla domanda del Tribunal Supremo, asserendo che «non si può escludere che segni figurativi siano in grado di richiamare direttamente nella mente del consumatore, come immagine di riferimento, i prodotti che beneficiano di una denominazione registrata, a motivo della loro vicinanza concettuale con siffatta denominazione».

- Ciò vale anche nel caso di prodotti simili non protetti, ma provenienti da un’area DOP?

In secondo luogo, il Tribunal Supremo chiede alla Corte UE se la tutela garantita dalla DOP vale anche nei confronti dei produttori localizzati nella stessa regione geografica, ma i cui prodotti non sono prodotti DOP.

Secondo la Corte UE, la normativa europea «non prevede alcuna deroga in favore di un produttore stabilito in un’area geografica corrispondente alla DOP e i cui prodotti, senza essere protetti da tale DOP, sono simili o comparabili a quelli protetti da quest’ultima». Pertanto anche a questa domanda va data una risposta affermativa.

Il motivo è molto semplice: se si introducesse una deroga in favore di prodotti simili non protetti, ma provenienti dalla stessa area DOP (in questo caso ci si riferisce a tutti gli altri formaggi prodotti nella regione geografica de La Mancha, ma non rientranti nella DOP «queso manchego»), si consentirebbe ad alcuni produttori di trarre «un vantaggio indebito dalla notorietà di tale denominazione».

- A quale nozione di consumatore bisogna fare riferimento?

Sempre secondo la Corte di Giustizia UE, spetta al giudice nazionale la relativa valutazione, avendo riguardo alla «presunta reazione del consumatore, essendo essenziale che il consumatore effettui un collegamento tra gli elementi controversi», ossia i «segni figurativi che evocano l’area geografica il cui nome fa parte di una denominazione d’origine […] e la denominazione registrata».

La nozione di «consumatore» a cui bisogna fare riferimento per valutare se l’utilizzo di immagini richiamati una DOP può ingenerare confusione sul mercato, è quella di «consumatore medio normalmente informato e ragionevolmente attento e avveduto», tenendo presente, tuttavia, che lo scopo della normativa europea è quella di «garantire una protezione effettiva e uniforme delle denominazioni registrate contro qualsiasi evocazione nel territorio dell’Unione».

Di conseguenza, conclude la Corte di Giustizia UE:

- la valutazione con riferimento al consumatore dello Stato membro potrebbe già da sola sufficiente a far scattare la tutela predisposta;

- tuttavia, il fatto che si possa escludere l’evocazione per il consumatore di uno Stato membro, non è di per sé sufficiente a escludere che l’utilizzo delle immagini possa ingenerare confusione nei consumatori.

La tutela del «Made in Italy»

La sentenza della Corte di Giustizia UE rappresenta un precedente importantissimo per il c.d. «Made in Italy», perché concede ai consorzi italiani di agire contro i produttori che – attraverso l’utilizzo di immagini evocative – cercano di ingenerare nel consumatore la convinzione che loro i prodotti siano di origine protetta.

I falsi prodotti DOP non rappresentano soltanto una forma di concorrenza sleale, attribuendo un «vantaggio indebito» derivante dalla notorietà di una denominazione, ma sono in grado di determinare un danno di immagine gravissimo ai produttori italiani, conosciuti in tutto il mondo per la loro eccellenza, e che nel 2017 hanno contribuito a creare un giro d’affari legato al turismo enogastronomico pari a più di 12 miliardi di euro.

Una questione che, in fin dei conti, non interessa, quindi, soltanto i produttori.

Distribuzione digitale – Quale strategia?

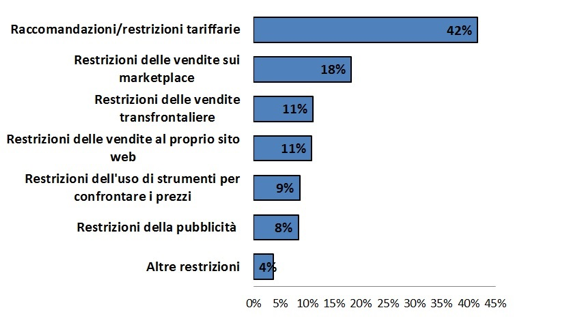

L’importanza della distribuzione via internet è aumentata nel corso degli anni, così come le restrizioni poste all’interno di contratti di distribuzione. Soprattutto i produttori di marchi rinomati mirano tanto a trarre vantaggio dalle opportunità del mercato digitale, quanto a preservare l’immagine dei loro prodotti. Conseguentemente, è frequente l’imposizione di diversi tipi di restrizioni sui distributori, come emerge dal seguente grafico (fonte: Commissione Europea, Relazione finale sull’indagine settoriale sul commercio elettronico, 10.05.2017):

Tali misure compaiono nella distribuzione selettiva, in quella esclusiva, nel franchising e nella distribuzione aperta. Alcune misure perseguono interessi legittimi, come quello di assicurare una distribuzione di alta qualità, mentre altre misure possono concretizzarsi in restrizioni anticoncorrenziali del territorio e del prezzo di rivendita. Mentre le restrizioni nel business online sono cresciute, la loro regolamentazione segue a rilento: la Corte di giustizia UE ha posto una prima pietra miliare nel 2011 con la sua decisione “Pierre Fabre” sul divieto generale di vendite su internet e, nel 2018, ne ha posta un’altra con la famosa pronuncia “Coty Germany” – entrambe riguardanti la distribuzione di prodotti (cosmetici) di lusso. Risultato:

“Un fornitore di prodotti di lusso può vietare ai suoi distributori autorizzati di vendere

i prodotti su una piattaforma Internet terza” (Comunicato stampa n. 132/17 del 6 dicembre 2017).

O, più brevemente l’Alta Corte Regionale di Francoforte nel 2018:

“Prodotti di lusso giustificano divieti di vendita online”.

(Comunicato stampa n. 30/2018 del 12 luglio 2018, in applicazione dei principi guida della suprema corte europea sui divieti di vendite online).

Per domande a cui sono state date risposte, altre ne sono sorte: solo il produttore di prodotti di lusso può proibire vendite online ai propri distributori? E se sì, che cos’è lusso? L’autorità per la concorrenza tedesca, il Bundeskartellamt, nella sua prima reazione dichiarava che la sentenza Coty dovrebbe applicarsi esclusivamente a prodotti originariamente di lusso:

“Produttori di marca non hanno ancora carte blanche su #divieti di piattaforme. Primo giudizio: “Limitato impatto sulla nostra attività” (Twitter, 6 dicembre 2017).

La Commissione Europea ha preso posizione in senso opposto, stabilendo che l’argomento della Corte nella decisione Coty dovrebbe applicarsi anche alla distribuzione di altri prodotti, senza aver riguardo al loro carattere di lusso:

“Le argomentazioni apportate dalla Corte sono valide indipendentemente dalla categoria di prodotto coinvolta (ossia beni di lusso nel caso di specie) e sono ugualmente applicabili a prodotti non di lusso. Che un divieto di usare piattaforme abbia l’obiettivo di restringere il territorio nel quale, o i consumatori a cui il distributore può vendere i prodotti, o se limita le vendite passive del distributore, non può logicamente dipendere dalla natura del prodotto coinvolto.” (Competition Policy Brief, aprile 2018)

Più di un anno dopo la decisione Coty, le norme non sono ancora al 100% chiare: tra i tribunali tedeschi, l’Alta Corte Regionale di Amburgo ha autorizzato il divieto di effettuare vendite su piattaforme terze anche con riguardo a prodotti non di lusso, i quali siano di alta qualità (decisione del 22 marzo 2018, fascicolo n. 3 U 250/16) – nella fattispecie, con riguardo a un sistema di distribuzione selettiva per integratori alimentari e cosmetici.

“se i beni venduti sono di alta qualità e la distribuzione è combinata a una consulenza al consumatore e servizi di assistenza paralleli, con lo scopo, tra gli altri, di illustrare al consumatore un prodotto finito e nel suo complesso sofisticato, di alta qualità e dal prezzo alto e di costruire o mantenere una specifica immagine del prodotto” (testo tradotto dalla versione originale in tedesco).

Di recente, il Bundeskartellamt tedesco ha preso nuovamente posizione, riaffermando la propria prima posizione:

“Le dichiarazioni della Corte di Giustizia UE, a tal riguardo, sono limitate a prodotti di lusso e non possono essere facilmente trasferite ad altri prodotti di marca (di alta qualità).” (Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen im Internetvertrieb nach Coty und Asics – wie geht es weiter?, 02.10.2018).

I fornitori i quali vogliano agire in modo prudente dovrebbero utlizzare ricorrere con cautela a divieti di usare piattaforme al di fuori della distribuzione selettiva di prodotti di lusso. Per uno sguardo generale sulla prassi corrente con clausole contrattuali modello, vedi Rohrßen, Vertriebsvorgaben im E-Commerce 2018: Praxisübersicht und Folgen des “Coty”-Urteils des EuGH, in: GRUR-Prax 2018, 39-41 (in tedesco).

La distribuzione diretta

In alternativa, o in aggiunta, alle restrizioni in capo ai distributori i produttori si affidano spesso alla distribuzione diretta, vuoi per conto proprio con i propri dipendenti, vuoi attraverso agenti commerciali o tramite commissionari. Ciò significa che il rischio della distribuzione cade soltanto in capo al produttore e ciò comporta un grande vantaggio: i fornitori sono fondamentalmente svincolati dalle restrizioni del diritto antitrust e possono persino stabilire il prezzo di rivendita. Questo ha portato ad un aumento della distribuzione diretta in tutte le categorie di prodotti, compreso anche il settore automobilistico.

La grande maggioranza dei contratti stipulati online tra imprese e consumatori viene ormai conclusa mediante la sottoscrizione online del contratto e il richiamo alle condizioni generali di vendita, predisposte unilateralmente dal venditore/fornitore di servizi e consultabili sul sito web. Altrettanto usualmente, tra le condizioni generali di vendita è presente una clausola di scelta della legge applicabile al contratto, solitamente a favore della legge del luogo dove l’impresa ha sede.

La Corte di Giustizia Europea con la pronuncia C‑191/15 (VKI contro Amazon EU, 28 luglio 2016) ha precisato i requisiti di validità di una clausola di scelta di legge inserita nelle condizioni generali di un contratto B2C (“Business to Consumer”) stipulato online. La sentenza ha avuto un impatto molto rilevante nella redazione delle condizioni generali di vendita o servizio, perché la mancanza dei requisiti imposti dalla Corte di Giustizia Europea produce l’invalidità della clausola e la sua inapplicabilità in un’eventuale vertenza. È il caso, quindi, di ripercorrere la decisione della Corte di Giustizia.

Il caso sottopostole riguardava un contratto stipulato proprio con questa modalità: Amazon EU – con sede in Lussemburgo – commercia con i suoi clienti austriaci attraverso il portale amazon.de e nelle condizioni generali di vendita aveva inserito la seguente clausola: «Si applica la legge lussemburghese con esclusione delle disposizioni della Convenzione delle Nazioni Unite in materia di contratti di vendita internazionale di merci».

Su richiesta di un’associazione di consumatori, la Corte Suprema Austriaca ha chiesto alla Corte di Giustizia Europea di verificare se una simile clausola potesse essere considerata abusiva ai sensi dell’art. 3, par. 1, della direttiva 93/13 a tutela dei consumatori nei contratti stipulati con un professionista: “Una clausola contrattuale, che non è stata oggetto di negoziato individuale, si considera abusiva se, malgrado il requisito della buona fede, determina, a danno del consumatore, un significativo squilibrio dei diritti e degli obblighi delle parti derivanti dal contratto”.

La Corte ha, in primo luogo, osservato che il diritto europeo consente in linea di principio che un imprenditore inserisca nelle sue condizioni generali una clausola di scelta di legge, anche quando essa non sia stata oggetto di trattativa individuale con il consumatore. A fronte di questa possibilità, il legislatore europeo (art. 6, par. 2, Regolamento Roma I) ha previsto un meccanismo di tutela per il consumatore, garantendogli in ogni caso il diritto a invocare le disposizioni imperative della legge dello Stato in cui egli risiede, indipendentemente dalla legge individuata nella clausola. Il consumatore, quindi, anche se non previsto dalla clausola, potrà utilizzare le disposizioni inderogabili dello Stato nel quale ha la residenza abituale se più favorevoli di quelle previste dalla legge scelta nelle condizioni generali.

La Corte Europea, però, ha anche considerato essenziale che il professionista informi il consumatore del suo diritto a invocare le disposizioni di legge imperative “interne”, per evitare che quest’ultimo – ignorando l’art. 6, par. 2 del Regolamento Roma I e facendo affidamento unicamente a quanto scritto nella clausola – sia dissuaso dall’agire in giudizio nei confronti dell’imprenditore.

Questa situazione, infatti, andrebbe a creare un significativo squilibrio dei diritti e degli obblighi delle parti derivanti dal contratto, rendendo la clausola abusiva ai sensi dell’articolo 3, paragrafo 1, della direttiva 93/13.

Come dovrà quindi essere formulata una clausola di scelta di legge all’interno delle condizioni generali predisposte per un contratto B2C? La soluzione viene offerta dalla stessa Corte di Giustizia.

La clausola di scelta della legge applicabile dovrà informare il consumatore che egli può beneficiare anche della tutela consumeristica assicuratagli dalle disposizioni imperative della legge dello stato dove abitualmente risiede.

Sarà, al contrario, abusiva qualunque clausola che induca in errore il consumatore, dandogli l’impressione che al contratto si applichi soltanto la legge dello stato dove l’imprenditore/professionista ha sede.

Questa sentenza offre lo spunto per una considerazione più generale: le aziende e i professionisti che operano nel mercato e-commerce, specialmente nel settore B2C, devono prestare particolare attenzione agli sviluppi non solo della normativa interna ed europea, ma anche delle normative e delle interpretazioni giurisprudenziali nei paesi i cui risiedono i potenziali consumatori dei prodotti o servizi venduti, sia che si tratti di vendite sui canali tradizionali, sia online, al fine di evitare di predisporre dei contratti che si rivelino poco efficaci o, ancor peggio, controproducenti.

Tutte le considerazioni finora svolte non riguardano la competenza giurisdizionale e l’eventuale inserimento nel contratto di una clausola di scelta del foro competente, che nei contratti B2C è generalmente sconsigliabile. In ambito europeo, infatti, il Regolamento Bruxelles I bis accorda al consumatore una tutela molto forte, che gli dà quasi sempre la possibilità di proporre l’azione giudiziale nel luogo dove ha la sua residenza abituale (cd. Foro del consumatore), obbligando il professionista – indipendentemente da clausole con diverso contenuto – a fare lo stesso.

On February 14, 2019, the European Commission proudly announced in a press release that the night before, the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission reached a political deal on the first-ever rules aimed at creating a fair, transparent and predictable business environment for businesses and traders when using online platforms.

The new Regulation is part of the strategic plan of the European authorities to establish a digital single market and has its origin in the Commission Communication on Online Platforms of May 2016. As a result, in April 2018 the Commission presented the proposal of a new regulation.

The new rules will apply to companies such as Google AdSense, DoubleClick , eBay and Amazon Marketplace, Google and Bing Search , Facebook and YouTube, Google Play and App Store, Facebook Messenger, PayPal, Zalando and Uber.

After having conducted a series of studies, workshops and a large public consultation, the European Commission explained in its 2016 Communication the importance of creating in Europe a favorable environment for the development of new online platforms. Indeed, the statistics are very disappointing: only 4% of the world’s market capitalization is represented by online platforms created in Europe. The champions in the field are the United States and Asia.

On the basis of this observation, the Commission has drawn up a list of challenges for the European lawmaker as follows:

- Ensuring a level playing field for comparable digital services

- Ensuring that online platforms act responsibly

- Fostering trust, transparency and ensuring fairness

- Keeping markets open and non-discriminatory to foster a data-driven economy

- Safeguarding a fair and innovation-friendly business environment

2 years after the Communication of the Commission, the new Regulation was born.

First of all, what are the conditions for the application of the regulation?

- companies using online platforms must have their place of establishment or residence in the European Union and

- goods or services must be offered to consumers in the Union.

(the place of establishment or residence of the providers of these services is not relevant to the application of the Regulation).

A strengthened obligation of transparency

The Regulation makes online platforms subject to transparency by obliging them to ensure that their terms and conditions:

- are drafted in a clear and unambiguous manner;

- are easily available for business users at all stages of their commercial relationship with the provider of online intermediation services, including in the pre-contractual stage;

- set out the objective grounds for decisions to suspend or terminate, in whole or in part, the provision of their online intermediation services to business users.

Ranking

Online platforms will have to indicate in their terms and conditions the main parameters determining ranking and the reasons for the relative importance of those main parameters as opposed to other parameters

Where those main parameters include the possibility to influence ranking against any direct or indirect remuneration paid by business users to the provider of online intermediation services concerned, that online platform shall also include in its terms and conditions a description of those possibilities and of the effects of such remuneration on ranking.

Differentiated treatment of goods or services

The online platform shall also include in their terms and conditions a description of any differential treatment they give on the one hand in relation to goods and services offered to consumers through these online intermediation services, either by the supplier himself or by any user enterprise controlled by that supplier and, secondly, in relation to other business users.

Access to data

The platforms will have to establish a description of the technical and contractual access, or lack of such access for business users, to any personal data or other data, or both, that user companies or the consumers transmit for the use of the online intermediation services concerned or which are generated through the provision of those services.

Prohibition of certain unfair practices

Prohibition of modification of the terms and conditions without notice

Any proposed amendment of terms and conditions shall be notified to users and the notice period shall be at least 15 days from the date on which the online platform notifies the business users concerned about the envisaged modifications.

Prohibition of suspension or termination without cause

Under Article 4 of the Regulation when intermediation service provider decides to suspend or terminate, in whole or in part, providing its services to a given user company, it shall provide the business user without undue delay, with the motivation for such a decision.

New avenues for dispute resolution

Internal complaint-handling system

Providers of online intermediation services will have to provide an internal complaint handling the complaints from user companies.

Mediation

The platforms shall identify in their terms and conditions one or more mediators with which they are willing to engage to attempt to reach an agreement with business users on the settlement, out of court, of any disputes between the provider and the business user arising in relation to the provision of the online intermediation services concerned, including complaints that could not be resolved by means of the internal complaint-handling system.

The Regulation specifies the conditions that mediators shall met in order to be able to carry out their mission.

Judicial proceedings by representative organizations or associations and by public bodies

Organisations and associations which have a legitimate interest in representing user undertakings or entities using a corporate website, as well as public bodies established in the Member States, shall have the right to bring an action before the national courts in the Union, in accordance with the rules of the law of the Member State in which the action is brought, with a view to putting an end to or prohibiting any infringement, by providers of online intermediation services or on-line search engines.

Coming into force

As it is announced by The European Commission, the new rules will apply 12 months after its adoption and publication, and will be subject to review within 18 months thereafter, in order to ensure that they keep pace with the rapidly developing market. The EU has also set up a dedicated Online Platform Observatory to monitor the evolution of the market and the effective implementation of the rules.

Online platforms regardless of your size, start drafting your new terms and conditions!

I franchisor (affilianti) possono condurre campagne pubblicitarie a prezzi bassi. Tali campagne, tuttavia, possono costare care, se le stesse hanno un effetto anticoncorrenziale, in particolare se, di fatto, forzano il franchisee (affiliato) a offrire i prodotti ai prezzi più bassi.

Un esempio interessante è quello della campagna sui prezzi per “l’hamburger della settimana”, oggetto della decisone del Tribunale regionale di Monaco di Baviera del 26 ottobre 2018 (fascicolo n. 37 O 10335/15).

Il caso

In aggiunta all’obbligazione di pagare royalties in cambio dell’uso dei sistemi di franchising e dei suoi marchi commerciali (5%), gli accordi di franchising obbligavano i franchisee a pagare un compenso per la pubblicità parametrato sull’andamento delle vendite. Il franchisor usava i compensi pagati per la pubblicità dai franchisee, tra le altre cose, per pubblicizzare prodotti presenti sul menù dei franchisee a prezzi bassi, ad esempio con lo slogan “King of the Month”.

Grazie alla partecipazione alle campagne pubblicitarie con relativi prezzi bassi, le vendite dei franchisee aumentavano e con esse anche le royalties che dovevano pagare al franchisor.

Dopo un po’ di tempo, però, i franchisee realizzarono che tale campagna pubblicitaria causava loro un danno economico, perché i prodotti offerti a un prezzo basso cannibalizzavano la vendita dei prodotti offerti a prezzo normale (“effetto di cannibalizzazione”). Di qui la decisione di non partecipare alla campagna e chiedere una riduzione appropriata del compenso pubblicitario da pagare e di agire in giudizio al fine di far bloccare l’applicazione del compenso per la pubblicità in relazione alla campagna pubblicitaria contestata.

Il Tribunale Regionale accoglieva entrambe le domande con la motivazione che le campagne pubblicitarie avevano un effetto restrittivo della concorrenza, ossia della facoltà per il franchisor di stabilire propri prezzi di vendita, in contrasto con il paragrafo 1 e 2 (2) della Legge tedesca sulle restrizioni della concorrenza e art. 2 (1), art. 4 a) del Regolamento Europeo di Esenzione per categoria in base agli accordi verticali. In sostanza, il franchisor determinava, secondo la Corte, il prezzo di rivendita tramite l’effetto vincolante di fatto della campagna pubblicitaria.

La decisione è in linea con la precedenza giurisprudenza, in particolare con le decisioni della Corte Federale tedesca su campagne su prezzi minimi di franchisor nei settori di

- Noleggio di autoveicoli (“Sixt ./. Budget”, 02.02.1999, fasc. n. KZR 11/97, par. 30),

- Cibo per animali (“Fressnapf”, 04.02.2016, fasc. n. I ZR 194/14, para. 14), e

- Occhiali nell’ambito di un sistema di distribuzione duale dove il franchisor vendeva i prodotti tramite le proprie filiali nonché tramite franchisee, senza far distinzione tra operazioni di filiale e di franchisee (“Apollo Optik”, 20.05.2003, fasc. n. KZR 27/02, para. 37).

Indicazioni pratiche

Le Obbligazioni che sono essenziali per far funzionare il sistema di franchise non restringono la competizione nell’ambito degli scopi delle norme UE sull’antitrust (in modo simile alla “dottrina delle restrizioni accessorie” presente nel diritto USA). In particolare, le seguenti restrizioni costituiscono i componenti tipicamente indispensabili per un accordo franchise applicabile:

- Restrizioni del trasferimento di know-how;

- Obbligazioni di non concorrenza (durante e dopo la scadenza dell’accordo), che proibiscano al franchisee di aprire un negozio di natura uguale o simile in una zona in cui potrebbe entrare in concorrenza con altri membri della rete di franchising;

- Obbligazioni del franchisee di non trasferire il proprio negozio senza previa approvazione del franchisor.

(cfr. Corte di Giustizia UE, 28.01.1986, caso “Pronuptia”, fasc. n. 161/84 par. 16 e 17).

I sistemi di franchise non sono esentati, di per sé, da divieti di restrizione di concorrenza. Perciò, si deve prestare attenzione nel conformarsi alle norme antitrust UE al fine di evitare pesanti sanzioni e assicurare l’esecuzione dell’accordo di franchising.

Il divieto di fissazione di prezzo (o imposizione del prezzo di rivendita) si applica alla relazione tra il franchisor e il franchisee se il franchisee sopporta il rischio economico della propria impresa. Al fine di evitare che una tale campagna pubblicitaria con prezzi di rivendita raccomandati costituisca una fissazione del prezzo contraria alla concorrenza, occorre valutare approfonditamente il caso concreto. Ciò che consente di escludere un effetto vincolante in via di fatto è:

- L’aggiunta di una nota chiarificatrice: “Solo a ristoranti partecipanti a… . Fino ad esaurimento scorte.”

- Assicurare che tale nota sia chiaramente visibile, per es. aggiungendo un asterisco “*” al prezzo.

- Evitare ogni misura che possa essere interpretata come pressione o incentivo per il franchisee e che trasformerebbe il prezzo raccomandato in un prezzo fisso (per es. perché un altro prezzo porterebbe a conseguenze negative).

Tali campagne pubblicitarie possono funzionare – come mostra una decisione di una Corte UK del 2009 (BBC, caso Burger King, dove i franchisee avevano contestato al franchisor che “ una promozione dell’impresa richiedeva all’affiliato di vendere un doppio cheeseburger per $1 per un costo di produzione di $1.10”. La Corte in quel caso aveva ritenuto legittima la campagna, sulla base degli elementi sopra indicati, I franchisor possono persino imporre il prezzo di rivendita, ma occorre che tali campagne siano preparate con grande attenzione.

Per un quadro d’insieme sul mantenimento di prezzi di rivendita, rimando al precedente articolo su Legalmondo Contratti di distribuzione e fissazione del prezzo minimo di rivendita.

Il mantenimento di prezzi di rivendita può costare caro. Nel 2018, la Commissione Europea ha emesso multe dell’ammontare di circa 111 milioni di euro contro quattro produttori di elettrodomestici di consumo – Asus, Denon & Marantz, Philips e Pioneer – per aver fissato prezzi online di vendita fissi (cfr. Il comunicato stampa del 24 luglio 2018).

The Spanish Law of the Agency Contract and the European Directive provide for the agent -except in certain cases-, goodwill compensation (clientele) when the relationship is terminated, based on the remuneration received by the Agent during the life of the contract. It is, then, a burden that in general every Principal will have pending when the contract ends.

The temptation is to try to get rid of that payment and for this clients consult us frequently about strategies or tactics. I will try to summarize some of them indicating the chances of success (or not) that may have, both in the negotiation / drafting phase of the contract, and in the resolution phase.

- Change the name of the contract

The first idea is to make a contract “similar” to the agency or call it in a different way (services, intermediation, representation contracts…). However, the change of name does not have any incidence since the contracts “are what they are” and not what the parties call them. So if there is a continued mediation in exchange for remuneration, there is a good chance that a judge will consider it an agency contract, whatever we call it, and with all its consequences.

- Limitation of compensation in the contract

Another temptation in the drafting phase of the contract is to agree compensation less than the maximum legally envisaged, provide for payment in advance for the duration of the contract, or directly eliminate it.

None of these solutions would be valid if they try to reduce the possibility of the Agent to receive the legal maximum, or for reasons not foreseen in the Law or the Directive. The law is imperative.

- Linking different agency contracts

Given that the compensation is calculated according to the remunerations of the last five years and the clientele created, the temptation is to link several shorter contracts to consider only the clients of the last period.

This will not necessarily be a good idea if most of the customers were created last year for instance, but it may also be useless because the Spanish law and the Directive provide that the fixed-term contract that continues to be executed becomes indefinite. The judge may consider all linked contracts as one.

For this strategy to have the possibility of being useful, it would be necessary to liquidate each substituted contract, declare that “nothing has to be claimed by the parties” and that the successive contracts are sufficiently separated and have different entities, drafting, extension, etc. If the procedure is well thought out, it could be a way to get rid of a greater indemnity by clientele: a well-written pact whereby the agent declares the compensation received, and the following contract does not mimic the content and immediately to the previous one.

- Submitting the agreement to a foreign law

In international contracts the temptation is to submit the contract to a right that is not Spanish, particularly when the Principal has that citizenship.

The idea can be good or bad according to the chosen law and as long as it has some relation with the business. As is known, in the EU the Directive establishes minimum conditions that national laws must respect. But nothing prevents these laws from providing more advantageous conditions for agents. This means that, for example, choosing French law would be, in general, a bad idea for the Principal because compensation in that country is usually higher.

In some cases, the choice of a law outside the European Union that does not provide compensation for clientele when the agent is European has been rejected because that the minimum right recognized in the Directive has not been respected.

- Submit the contract to non-national rules and judges

Another less frequent possibility is to submit the contract to rules not from a country, but to general commercial norms (Lex Mercatoria) and to agree on a lower compensation.

This is very uncommon and may not be very useful depending on who is to interpret the contract and where the agent resides. If, for example, the agent resides in Spain and who is going to interpret the contract is a Spanish judge, he will most likely interpret the contract according to his/her own rules without being bound by what the contract envisages. This clause would have been useless.

- Submit the contract to arbitration

The question will be different if the contract is subject to arbitration. In this case, arbitrators are not necessarily subject to interpreting a contract according to their own national regulations if the contract is subject to different one. In this case, it would be possible that they felt freer to consider the contract exclusively, especially when the agent was not of their nationality, did not know what the law of the agent’s country and was not bound by the guarantees provided for his protection.

- Mediation in the agency contract

Mediation is an alternative dispute resolution system that can also be used in agency contracts. In mediation, the parties resolve the dispute by themselves with the help of a mediator.

In this case, given that the mediator is not deciding, it is possible for the parties to freely reach an agreement whereby the agent agrees to a minor indemnification if, for example, other advantages are conferred upon him, if he comes to the conviction of having less right, difficulty of proof, if he prefers to save other costs, time, energy for your new business, etc.

Mediators ensure the balance of the parties, but nothing prevents them to agree a compensation lower than the legal maximum (after the conclusion of the contract it is possible to negotiate a lower than the legal maximum). To foresee the possibility of mediation in the agency contract is, therefore, a good idea: this will permit the parties to better address and negotiate this compensation. In addition, providing for mediation does not limit the rights of any of the parties to withdraw and continue through the courts demanding the legal maximum.

- Imputing to the agent a previous breach

When the contract ends, this is undoubtedly the cause that is most often attempted: when the contract is to be resolved, the Principal tries to argue that the Agent has previously failed to comply and that this is why the contract is being resolved.

The law and the Directive exempt the payment of goodwill compensation when the agent has breach his obligations. But in that case, the Principal must be able to prove it when the agent discusses it. And it will not always be easy. The Principal must provide clear evidence and for this it will be convenient to collect information and documentation on the breach sufficiently and in advance and of sufficient importance (minor breaches are not usually accepted). Therefore, if the Principal wishes to follow this path it is advisable to prepare the arguments and evidences time before the agreement ends. It is strongly recommend contacting an expert advisor as soon as possible: he will help you to minimize the risks.

„Prodotti di lusso giustificano divieti di distribuire su piattaforme terze” recita il Comunicato stampa n. 30/2018 della Corte d’Appello di Francoforte del 12.07.2018.

Dopo la sentenza Coty della CGUE, a lungo attesa (vedi l’articolo di dicembre 2017 https://www.legalmondo.com/it/2017/12/corte-di-giustizia-ue-ammette-la-restrizione-alle-vendite-online-sentenza-coty/), la Corte d’Appello di Francoforte sul Meno ha applicato le indicazioni della CGUE, (i) ribadendo la possibilità di limitare la rivendita attraverso piattaforme terze. Nel corso di questo post, inoltre, vedremo anche la (ii) recente pronuncia della Corte d’Appello di Amburgo, che ha esteso il principio della sentenza Coty anche ad altre merci dal valore qualitativo elevato, ma al di fuori del segmento del lusso. In conclusione, poi, (iii) alcuni suggerimenti pratici.

Prodotti di lusso giustificano i divieti di usare piattaforme

Ai sensi della sentenza della Corte d’Appello di Francoforte, Coty può inibire al distributore la distribuzione tramite piattaforme di terzi. Nel contratto di distribuzione selettiva adottato da Coty, ogni rivenditore era libero di instaurare cooperazioni pubblicitarie con piattaforme terze, nelle quali i clienti vengono indirizzati al negozio internet del rivenditore. Il divieto di distribuzione su market-place, sarebbe invece ammissibile già sulla base del Regolamento sulle esenzioni per categorie di accordi verticali, in quanto non rappresenterebbe una restrizione fondamentale. Il divieto di distribuzione potrebbe essere esentato persino dal divieto di cartelli nell’ambito di una distribuzione selettiva; nel presente caso sarebbe soltanto dubbio se il divieto di qualsiasi “cooperazione di vendita con una piattaforma terza riconoscibile esternamente da altri e senza riguardo alla sua concreta strutturazione stia in rapporto ragionevole con il fine perseguito” (testo tradotto dall’originale in tedesco), sia quindi proporzionato o incida sull’attività concorrenziale del rivenditore. La Corte ha lasciato aperta questa questione.

Anche altri merci di alto valore giustificano i divieti di usare piattaforme

Il caso deciso dalla Corte d’Appello di Amburgo (Decisione del 22.03.2018, fasc. n. 3 U 250/16) concerne un sistema di distribuzione selettiva qualitativo per integratori alimentari e cosmetici, il quale avviene tramite Network Marketing così come via Internet. Le linee guida distributive contengono, tra le altre cose, concrete indicazioni sulla pagina internet del rivenditore, possibilità di prendere direttamente contatto con i clienti in base al “principio della vendita di merci fatta su persona” (in quanto il sistema distributivo mira a vendere il prodotto tagliato sulle esigenze personali dei clienti nell’ambito di una consulenza personalizzata) così come della qualità dell’informazione e della rappresentazione del prodotto. Espressamente vietata sarebbe “la distribuzione … tramite eBay e altre piattaforme commerciali internet paragonabili”, in quanto esse non sarebbero conformi ai requisiti qualitativi, in ogni caso non “in base allo stato attuale” (testo tradotto dall’originale in tedesco).

Il Tribunale di prima istanza ha ritenuto ammissibile il divieto di far uso di piattaforme (Tribunale di Amburgo, sentenza del 04.11.2016, fasc. n. 315 O 396/15) – cosa che la Corte d’Appello di Amburgo ha ora confermato. Ciò in quanto, secondo la Corte d’Appello, sistemi di distribuzione selettiva qualitativi sarebbero ammissibili non solo per beni di lusso e tecnicamente dal valore alto, bensì anche per (ulteriori) merci di alto valore qualitativo, “qualora le merci distribuite siano di alta qualità e la distribuzione sia indirizzata a prestazioni accompagnatorie di consulenza e assistenza per il cliente, con cui tra l’altro si persegue il fine di spiegare al cliente un prodotto finale il quale nel complesso sia sofisticato, qualitativamente di alto valore e dal prezzo elevato e di costruire o conservare una particolare immagine del prodotto” (testo tradotto dall’originale in tedesco).

Nell’ambito di un tale sistema di distribuzione selettiva per la distribuzione di integratori alimentari e cosmetici potrebbe quindi essere ammissibile “tramite corrispondenti linee guida d’impresa, vietare al partner distributivo la distribuzione di tali merci su determinate piattaforme di vendita online, al fine di preservare l’immagine di prodotto e la prassi di una consulenza legata al cliente in grado di contribuire a creare tale immagine, così come al fine di evitare pratiche commerciali di singoli partner distributivi lesive dell’immagine del prodotto e dell’immagine, le quali siano state accertate nel passato e conseguentemente perseguite” (testo tradotto dall’originale in tedesco).

Una particolarità qui: non si trattava di “puri prodotti di prestigio“ – inoltre la Corte d’Appello non si era limitata all’accertamento che il divieto di usare piattaforme fosse ammissibile ai sensi dell’art. 2 Regolamento sulle esenzioni per categorie di accordi verticali e pratiche concordate, ma la Corte ha declinato in modo preciso e passo-passo i c.d. criteri Metro.

Conclusioni

- Internet resta un motore di crescita per beni di consumo, come anche i dati di mercato della associazione commercianti della Germania confermano: “Online-Handel bleibt Wachstumstreiber“.

- Al tempo stesso, proprio i produttori di marca vogliono una crescita regolata ai sensi delle regole del loro sistema di distribuzione e secondo le loro indicazioni. Di ciò fanno parte, proprio per prodotti di lusso e tecnicamente sofisticati così come ulteriori prodotti richiedenti una consulenza intensiva, indicazioni stringenti sulla pubblicazione della marca e sulla pubblicità (indicazioni su clausole applicabili a negozi fisici, divieti di piazze di mercato) e sui servizi da fornire (ad es. chat e/o numero telefonico con indicazioni sulla disponibilità).

- I produttori dovrebbero verificare se i loro divieti di usare piattaforme siano conformi ai requisiti della CGUE oppure se essi possono instaurare divieti di usare piattaforme – nella distribuzione selettiva, esclusiva, di franchising e in quella aperta.

- Chi vuole correre minori rischi possibili, dovrebbe, al di fuori della distribuzione selettiva di merci di lusso, essere ancora prudente con divieti di usare piattaforme – ciò in quanto anche l’Ufficio Federale dei Cartelli ha come prima reazione dichiarato che la sentenza Coty vale solo per prodotti originariamente di lusso: “#Produttori di marca non hanno, ora come prima, nessuna carta bianca per #divieti di piattaforme. Prima valutazione: Ripercussioni limitate sulla nostra prassi” (BKartA su Twitter, 6.12.2017). In senso contrario si è ora posizionata la Commissione Europea: nella sua “Competition Policy Brief” di Aprile 2018 („EU competition rules and marketplace bans: Where do we stand after the Coty judgment?“) la Commissione – alquanto tra parentesi – tiene fermo il fatto che l’argomentazione adottata dalla CGUE nel caso Coty vale anche indipendentemente dal carattere di lusso dei prodotti distribuiti:

“Gli argomenti prodotti dalla Corte sono validi indipendentemente dalla categoria di prodotti coinvolti (ossia, nel caso di specie, beni di lusso) e sono applicabili egualmente a prodotti non di lusso. Se un divieto di usare piattaforme ha l’obiettivo di restringere il territorio in cui il prodotto può essere venduto o i consumatori a cui il distributore può vendere i prodotti o se limita le vendite passive del distributore, ciò non può logicamente dipendere dalla natura del prodotto coinvolto.” (traduzione dal testo originale in inglese)

Effettivamente la Corte di Giustizia UE nella sentenza ha definito “merci di lusso” in modo ampio: come merci la cui qualità “non poggia solo sulle sue caratteristiche materiali”, bensì su valori immateriali – cosa che per quanto riguarda merci di marca generalmente risulta vero (cfr. sentenza Coty della Corte di Giustizia UE del 06.12.2017, n. 25 così come, per quanto riguarda “merci di qualità”, le Conclusioni finali del 26.07.2017 dell’Avvocato Generale presso l’UE, n. 92). Inoltre la Corte di Giustizia UE richiede soltanto che le merci siano comprate “anche” per il loro carattere di prestigio, non “soltanto” o “soprattutto” per quello. Tutto ciò gioca a favore dei produttori di marca, che pare possano assumere divieti di utilizzo di piattaforme nei loro contratti di distribuzione – quantomeno entro una quota di mercato fino a un massimo del 30%.

- Chi non ha alcun timore di affrontare rivenditori e autorità dei cartelli, può erigere divieti di utilizzo di piattaforme assolutamente anche al di fuori della distribuzione selettiva di merci di lusso – o puntare in modo ancora più forte su prodotti Premium o di lusso – come ad esempio nel caso della catena di profumi Douglas (cfr. Süddeutsche Zeitung dell’08.03.2018, pag. 15: “Attiva e non convenzionale, Tina Müller termina gli sconti presso Douglas e punta sul lusso”(traduzione dal testo originale in tedesco)).

- Per assicurare una qualità uniforme della distribuzione si possono inserire delle indicazioni qualitative stringenti, soprattutto rispetto alla distribuzione online. La lista delle possibili indicazioni qualitative è molto ampia. Tra questi, si riportano alcune “Best Practice” piuttosto frequenti:

– Il posizionamento come rivenditore (piattaforma, assortimento, comunicazione)

– la configurazione della pagina internet (qualità, l’impressione, ecc.)

– il contenuto e l’offerta di prodotto della pagina internet,

– la esecuzione delle compravendite online,

– la consulenza e il servizio clienti così come

– la pubblicità.

- Essenziale è inoltre che i produttori non possono vietare completamente il commercio internet ai rivenditori e le indicazioni distributive non possono nemmeno avvicinarsi a un tale completo divieto – come ora vedono i tribunali nel caso del divieto di usare strumenti di ricerca dei prezzi da parte di Asics, vedi a tal riguardo l’articolo dell’aprile 2018 (https://www.legalmondo.com/it/2018/04/germania-divieto-strumenti-di-comparazione-prezzi-e-pubblicita-su-piattaforme-terze/).

- Ulteriori dettagli sono presenti nelle riviste giuridiche in lingua tedesca:

– Rohrßen, Vertriebsvorgaben im E-Commerce 2018: Praxisüberblick und Folgen des „Coty“-Urteils des EuGH, in: GRUR-Prax 2018, 39-41

– Rohrßen, Internetvertrieb von Markenartikeln: Zulässigkeit von Plattform-verboten nach dem EuGH-Urteil Coty, in: DB 2018, 300-306

– Rohrßen, Internetvertrieb: „Nicht Ideal(o)“ – Kombination aus Preissuchmaschinen-Verbot und Logo-Klausel, in: ZVertriebsR 2018, 120-123

– Rohrßen, Internetvertrieb nach Coty – Von Markenware, Beauty und Luxus: Plattformverbote, Preisvergleichsmaschinen und Geoblocking, in: ZVertriebsR 2018, 277-285.

If 2017 was the year of Initial Coin Offerings, 2018 was the year of Blockchain awareness and testing all over the world. From ICO focused guidelines and regulations respectively aimed to alarm and protect investors, we have seen the shift, especially in Europe, to distributed ledger technology (“DLT”) focused guidelines and regulations aimed at protecting citizens on one hand and promote DLT implementations on the other.

Indeed, European Union Member States and the European Parliament started looking deeper into the technology by, for instance, calling for consultations with professionals in order to understand DLT’s potentials for real-world implementations and possible risks.

In this article I am aiming to give a brief snapshot of firstly what are the most notable European initiatives and moves towards promoting Blockchain implementation and secondly current challenges faced by European law makers when dealing with the regulation of distributed ledger technologies.

Europe

Let’s start from the European Blockchain Partnership (“EBP”), a statement made by 25 EU Member States acknowledging the importance of distributed ledger technology for society, in particular when it comes to interoperability, cyber security and efficiency of digital public services. The Partnership is not only an acknowledgement, it is also a commitment from all signatory states to collaborate to build what they envision will be a distributed ledger infrastructure for the delivering of cross-border public services.

Witness of the trust given to the technology is My Health My Data, a EU-backed project that uses DLT to enable patients to efficiently control their digitally recorded health data while securing it from the threat of data breaches. Benefits the EU saw in DLT on this specific project are safety, efficiency but most notably the opportunity that DLT offers data subject to have finally control over their own data, without the need for intermediaries.

Another important initiative proving European interests in testing DLT technologies is the Horizon Prize on “Blockchains for Social Good”, a 5 million Euros worth challenge open to innovators and tech companies to develop scalable, efficient and high-impact decentralized solutions to social innovation challenges.

Moving forward, in December last year, I had the honor to be part of the “ Workshop on Blockchains & Smart Contracts Legal and Regulatory Framework” in Paris, an initiative supported by the EU Blockchain Observatory and Forum (“EUBOF”), a pilot project initiated by the European Parliament. Earlier last year other three workshops were held, the aim of each was to collect knowledge on specific topics from an audience of leading DLT legal and technical professionals. With the knowledge collected, the EUBOF followed up with reports of what was discussed during the workshop and suggest a way forward.

Although not binding, these reports give a reasonably clear guideline to the industry on how existing laws at a European level apply to the technology, or at least should be interpreted, and highlight areas where new regulation is definitely needed. As an example let’s look at the Report on Blockchain & GDPR. If you missed it, the GDPR is the Regulation that protects Europeans personal data and it’s applicable to all companies globally, which are processing data from European citizens. The “right to erasure” embedded in the GDPR, doesn’t allow personal data to be stored on an immutable database, the data subject has to be able to erase data anytime when shared with a service provider and stored somewhere on a database. In the case of Blockchain, the consensus on personal data having to be stored off-chain is therefore unanimous. Storing personal data off-chain and leaving an hash to that data on-chain, is a viable solution if certain precautions are taken in order to avoid the risks of reversibility or linkability of such hash to the personal data stored off-chain, therefore making the hash on-chain personally identifiable information.

However, not all European laws apply to Member States, therefore making it hard to give a EU-wide answer to most DLT compliance challenges in Europe. Member States freedom to legislate is indeed only limited/influenced by two main instruments, Regulations, which are automatically enforceable in each Member State and Directives binding Member States to legislate on specific topics according to a set of specific rules.

Diverging national laws have a great effect on multiple aspects of innovative technologies. Let’s look for instance at the validity of “smart contracts”. When discussing the legal power of automatically enforceable digital contracts, the lack of a European wide legislation on contracts makes it impossible to find an answer applicable to all Member States. For instance, is “offer and acceptance” enough to constitute a contract? What is considered a valid “acceptance”? What is an “obligation”? “Can a digital asset be the object of a legally binding agreement”?

If we try to give a EU-wide answer to the questions such as smart contract validity and enforceability it is apparently not possible since we will need to consider 28 different answers. I, therefore, believe that the future of innovation in Europe will highly depend on the unification of laws.

An example of a unified law that has great benefits on innovation (including DLT) is the Electronic Identification and Trust Services (eIDAS) Regulation, which governs electronic identification including electronic signatures.

The race to regulating DLT in Europe

Let’s now look briefly at a couple of Member States legislations, specifically on Blockchain and cryptocurrencies last year.

EU Member States have been quite creative I would say in regulating the new technology. Let’s start from Malta, which saw a surprising increase of important projects and companies, such as Binance, landing on the beautiful Mediterranean Island thanks to its favorable (or at least felt as such) legislations on DLT. The “Blockchain Island” passed three laws in early July to regulate and supervise Blockchain projects including ICOs, crypto exchanges and DLT, specifically: The Innovative Technology Arrangements and Services Act regulation that aims at recognizing different technology arrangements such as DAOs, smart contracts and in future probably AI machines; The Virtual Financial Assets Act for ICOs and crypto exchanges; The Malta Digital Innovation Authority establishing a new supervisory authority.

Some think the Maltese legislation lacks a comprehensive framework, one that for instance, gives legal personality to Innovative Technology Arrangements. For this reason some are therefore accusing the Maltese lawmakers of rushing into an uncompleted regulatory framework in order to attract business to the island while others seem to positively welcome the laws as a good start for a European wide regulation on DLT and crypto assets.

In December 2018, Malta also initiated a declaration that was then signed by other six Members States, calling for collaboration for the promotion and implementation of DLT on a European level.

France was one of the signatories of such declaration, and it’s worth mentioning since the French Minister for the Economy and Finance approved in September a framework for regulating ICOs and therefore protecting investors’ rights, basically giving the AMF (French Authority for Financial Market) the empowerment to give licenses to companies wanting to raise funds through Initial Coin Offerings.

Last but not least comes Switzerland which although it is not a EU Member State, it has great degree of influence on European and national legislators when it comes to progressive regulations. At the end of December, the Swiss Federal Council released a report on DLT and the law, making a clear statement that the existing Swiss law is sufficient to regulate most matters related to DLT and Blockchain, although some adjustments have to be made. So no new laws but few amendments here and there, which will allow the integration of the specific DLT applications with existing laws in order to ensure legal certainty on certain uncovered matters. Relevant areas of Swiss law that will be amended include the transfer of rights utilizing digital registers, Anti Money Laundering rules specifically for decentralized trading platforms and bankruptcy when that proceeding involves crypto assets.

Conclusions

To summarize, from the approach taken during the past year, it is apparent that there is great interest in Europe to understand the potentials and to soon test implementations of distributed ledger technology. Lawmakers have also an understanding that the technology is in an infant state, it might involve risks, therefore making it complex to set specific rules or to give final answers on the alignment of certain technology applications with existing European or national laws.

To achieve European wide results, however, acknowledgments, guidelines and reports are not enough. The setting of standards for lawmakers applicable to all Member States or even unification of laws in crucial sectors influencing directly or indirectly new technologies, will be the only solution for any innovative technology to be adopted at a European level.

The author of this post is Alessandro Mazzi.

Scrivi a Benedikt

Condizioni generali dei contratti online B2C: la clausola di scelta della legge applicabile

28 Marzo 2019

-

Europa

- Contratti

- eCommerce

Con la recentissima pronuncia del 2 maggio 2019 (causa C-614/17), la Corte di Giustizia UE ha stabilito che la normativa europea in tema di protezione delle indicazioni geografiche e delle denominazioni d’origine dei prodotti agricoli ed alimentari deve essere interpretata nel senso che «l’utilizzo di segni figurativi che evocano l’area geografica alla quale è collegata una denominazione d’origine […] può costituire un’evocazione [vietata dalla normativa europea, n.d.r.] della medesima anche nel caso in cui i suddetti segni figurativi siano utilizzati da un produttore stabilito in tale regione, ma i cui prodotti, simili o comparabili a quelli protetti da tale denominazione d’origine, non sono protetti da quest’ultima».

Questa sentenza, che prende spunto dal curioso caso dei formaggi de La Mancha, rappresenta una pietra miliare per la tutela delle eccellenze enogastronomiche nazionali, con importanti risvolti sui prodotti «Made in Italy».

Il caso

Il caso trae origine dalla commercializzazione, da parte dell’Industrial Quesera Cuquerella SL [«IQC»], di alcuni formaggi attraverso l’utilizzo di etichette evocative del noto personaggio di Miguel de Cervantes, ossia Don Chisciotte de La Mancha.

Nella sostanza, si trattava di etichette contenenti raffigurazioni tradizionali di Don Chisciotte, di un cavallo magro evocativo del cavallo «Ronzinante» e di paesaggi con mulini a vento, per commercializzare i formaggi «Super Rocinante», «Rocinante» e «Adarga de Oro» [il termine «adarga» rappresenta un arcaismo spagnolo, utilizzato da Miguel de Cervantes per indicare lo scudo di Don Chisciotte, n.d.r.], non compresi, però, all’interno del DOP «queso manchego» [formaggio de La Mancha, in spagnolo, n.d.r.].

Per tale ragione, la Fondazione Queso Manchego [«FQM»], incaricata della gestione e della protezione della DOP «queso manchego», si rivolgeva al giudice spagnolo, affinché dichiarasse che tale utilizzo, riguardando formaggi non compresi nella DOP, rappresentava una violazione della normativa europea in tema di protezione delle indicazioni geografiche e delle denominazioni d’origine dei prodotti agricoli ed alimentari di cui al Regolamento U.E. 510/2016.

La decisione dei giudici spagnoli ed il rinvio del Tribunal Supremo

Tanto in primo che poi in secondo grado, i giudici spagnoli rigettavano la richiesta della FQM, ritenendo che l’utilizzo di immagini evocative de La Mancha per commercializzare formaggi non protetti dalla DOP «queso manchego», fosse in grado di indurre il consumatore a pensare, appunto, alla regione spagnola, ma non necessariamente alla DOP «queso manchego».

FQM si rivolgeva, quindi, al Tribunal Supremo spagnolo, che rinviava la questione alla Corte di Giustizia UE, ritenendo necessario, per risolvere il caso concreto, sapere come debba essere interpretata la normativa europea ed osservando che:

- il termine «manchego» in spagnolo qualifica ciò che è originario de La Mancha e che la DOP «queso manchego» protegge i formaggi di pecora provenienti da tale regione e prodotti rispettando quanto previsto nel relativo disciplinare;

- i nomi e le immagini utilizzate da IQC per commercializzare i propri formaggi, non protetti dalla DOP «queso manchego», richiamano Don Chisciotte e La Mancha, a cui tale personaggio è tradizionalmente associato.

La decisione della Corte di Giustizia UE

Con la sentenza del 02 maggio 2019, la Corte di Giustizia UE risponde ai quesiti posti dal Tribunal Supremo spagnolo.

- I segni figurativi sono in grado di ingenerare confusione nel consumatore?

Il Tribunal Supremo spagnolo chiede alla Corte UE di chiarire se l’uso di segni figurativi per evocare una DOP è in grado di per sé di ingenerare confusione nel consumatore.

La Corte, tenendo conto della volontà del legislatore UE di dare ampia protezione alle DOP, ha dato una risposta affermativa alla domanda del Tribunal Supremo, asserendo che «non si può escludere che segni figurativi siano in grado di richiamare direttamente nella mente del consumatore, come immagine di riferimento, i prodotti che beneficiano di una denominazione registrata, a motivo della loro vicinanza concettuale con siffatta denominazione».

- Ciò vale anche nel caso di prodotti simili non protetti, ma provenienti da un’area DOP?

In secondo luogo, il Tribunal Supremo chiede alla Corte UE se la tutela garantita dalla DOP vale anche nei confronti dei produttori localizzati nella stessa regione geografica, ma i cui prodotti non sono prodotti DOP.

Secondo la Corte UE, la normativa europea «non prevede alcuna deroga in favore di un produttore stabilito in un’area geografica corrispondente alla DOP e i cui prodotti, senza essere protetti da tale DOP, sono simili o comparabili a quelli protetti da quest’ultima». Pertanto anche a questa domanda va data una risposta affermativa.

Il motivo è molto semplice: se si introducesse una deroga in favore di prodotti simili non protetti, ma provenienti dalla stessa area DOP (in questo caso ci si riferisce a tutti gli altri formaggi prodotti nella regione geografica de La Mancha, ma non rientranti nella DOP «queso manchego»), si consentirebbe ad alcuni produttori di trarre «un vantaggio indebito dalla notorietà di tale denominazione».

- A quale nozione di consumatore bisogna fare riferimento?

Sempre secondo la Corte di Giustizia UE, spetta al giudice nazionale la relativa valutazione, avendo riguardo alla «presunta reazione del consumatore, essendo essenziale che il consumatore effettui un collegamento tra gli elementi controversi», ossia i «segni figurativi che evocano l’area geografica il cui nome fa parte di una denominazione d’origine […] e la denominazione registrata».

La nozione di «consumatore» a cui bisogna fare riferimento per valutare se l’utilizzo di immagini richiamati una DOP può ingenerare confusione sul mercato, è quella di «consumatore medio normalmente informato e ragionevolmente attento e avveduto», tenendo presente, tuttavia, che lo scopo della normativa europea è quella di «garantire una protezione effettiva e uniforme delle denominazioni registrate contro qualsiasi evocazione nel territorio dell’Unione».

Di conseguenza, conclude la Corte di Giustizia UE:

- la valutazione con riferimento al consumatore dello Stato membro potrebbe già da sola sufficiente a far scattare la tutela predisposta;

- tuttavia, il fatto che si possa escludere l’evocazione per il consumatore di uno Stato membro, non è di per sé sufficiente a escludere che l’utilizzo delle immagini possa ingenerare confusione nei consumatori.

La tutela del «Made in Italy»

La sentenza della Corte di Giustizia UE rappresenta un precedente importantissimo per il c.d. «Made in Italy», perché concede ai consorzi italiani di agire contro i produttori che – attraverso l’utilizzo di immagini evocative – cercano di ingenerare nel consumatore la convinzione che loro i prodotti siano di origine protetta.

I falsi prodotti DOP non rappresentano soltanto una forma di concorrenza sleale, attribuendo un «vantaggio indebito» derivante dalla notorietà di una denominazione, ma sono in grado di determinare un danno di immagine gravissimo ai produttori italiani, conosciuti in tutto il mondo per la loro eccellenza, e che nel 2017 hanno contribuito a creare un giro d’affari legato al turismo enogastronomico pari a più di 12 miliardi di euro.

Una questione che, in fin dei conti, non interessa, quindi, soltanto i produttori.

Distribuzione digitale – Quale strategia?

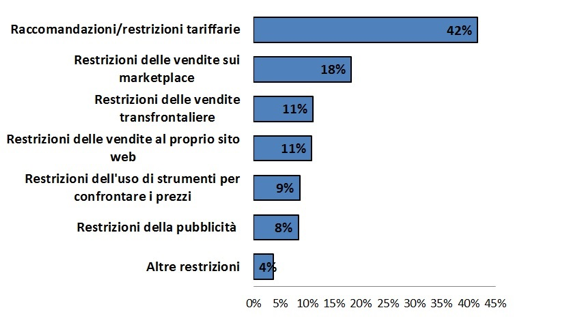

L’importanza della distribuzione via internet è aumentata nel corso degli anni, così come le restrizioni poste all’interno di contratti di distribuzione. Soprattutto i produttori di marchi rinomati mirano tanto a trarre vantaggio dalle opportunità del mercato digitale, quanto a preservare l’immagine dei loro prodotti. Conseguentemente, è frequente l’imposizione di diversi tipi di restrizioni sui distributori, come emerge dal seguente grafico (fonte: Commissione Europea, Relazione finale sull’indagine settoriale sul commercio elettronico, 10.05.2017):

Tali misure compaiono nella distribuzione selettiva, in quella esclusiva, nel franchising e nella distribuzione aperta. Alcune misure perseguono interessi legittimi, come quello di assicurare una distribuzione di alta qualità, mentre altre misure possono concretizzarsi in restrizioni anticoncorrenziali del territorio e del prezzo di rivendita. Mentre le restrizioni nel business online sono cresciute, la loro regolamentazione segue a rilento: la Corte di giustizia UE ha posto una prima pietra miliare nel 2011 con la sua decisione “Pierre Fabre” sul divieto generale di vendite su internet e, nel 2018, ne ha posta un’altra con la famosa pronuncia “Coty Germany” – entrambe riguardanti la distribuzione di prodotti (cosmetici) di lusso. Risultato:

“Un fornitore di prodotti di lusso può vietare ai suoi distributori autorizzati di vendere

i prodotti su una piattaforma Internet terza” (Comunicato stampa n. 132/17 del 6 dicembre 2017).

O, più brevemente l’Alta Corte Regionale di Francoforte nel 2018:

“Prodotti di lusso giustificano divieti di vendita online”.

(Comunicato stampa n. 30/2018 del 12 luglio 2018, in applicazione dei principi guida della suprema corte europea sui divieti di vendite online).

Per domande a cui sono state date risposte, altre ne sono sorte: solo il produttore di prodotti di lusso può proibire vendite online ai propri distributori? E se sì, che cos’è lusso? L’autorità per la concorrenza tedesca, il Bundeskartellamt, nella sua prima reazione dichiarava che la sentenza Coty dovrebbe applicarsi esclusivamente a prodotti originariamente di lusso:

“Produttori di marca non hanno ancora carte blanche su #divieti di piattaforme. Primo giudizio: “Limitato impatto sulla nostra attività” (Twitter, 6 dicembre 2017).

La Commissione Europea ha preso posizione in senso opposto, stabilendo che l’argomento della Corte nella decisione Coty dovrebbe applicarsi anche alla distribuzione di altri prodotti, senza aver riguardo al loro carattere di lusso:

“Le argomentazioni apportate dalla Corte sono valide indipendentemente dalla categoria di prodotto coinvolta (ossia beni di lusso nel caso di specie) e sono ugualmente applicabili a prodotti non di lusso. Che un divieto di usare piattaforme abbia l’obiettivo di restringere il territorio nel quale, o i consumatori a cui il distributore può vendere i prodotti, o se limita le vendite passive del distributore, non può logicamente dipendere dalla natura del prodotto coinvolto.” (Competition Policy Brief, aprile 2018)

Più di un anno dopo la decisione Coty, le norme non sono ancora al 100% chiare: tra i tribunali tedeschi, l’Alta Corte Regionale di Amburgo ha autorizzato il divieto di effettuare vendite su piattaforme terze anche con riguardo a prodotti non di lusso, i quali siano di alta qualità (decisione del 22 marzo 2018, fascicolo n. 3 U 250/16) – nella fattispecie, con riguardo a un sistema di distribuzione selettiva per integratori alimentari e cosmetici.

“se i beni venduti sono di alta qualità e la distribuzione è combinata a una consulenza al consumatore e servizi di assistenza paralleli, con lo scopo, tra gli altri, di illustrare al consumatore un prodotto finito e nel suo complesso sofisticato, di alta qualità e dal prezzo alto e di costruire o mantenere una specifica immagine del prodotto” (testo tradotto dalla versione originale in tedesco).

Di recente, il Bundeskartellamt tedesco ha preso nuovamente posizione, riaffermando la propria prima posizione:

“Le dichiarazioni della Corte di Giustizia UE, a tal riguardo, sono limitate a prodotti di lusso e non possono essere facilmente trasferite ad altri prodotti di marca (di alta qualità).” (Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen im Internetvertrieb nach Coty und Asics – wie geht es weiter?, 02.10.2018).

I fornitori i quali vogliano agire in modo prudente dovrebbero utlizzare ricorrere con cautela a divieti di usare piattaforme al di fuori della distribuzione selettiva di prodotti di lusso. Per uno sguardo generale sulla prassi corrente con clausole contrattuali modello, vedi Rohrßen, Vertriebsvorgaben im E-Commerce 2018: Praxisübersicht und Folgen des “Coty”-Urteils des EuGH, in: GRUR-Prax 2018, 39-41 (in tedesco).

La distribuzione diretta

In alternativa, o in aggiunta, alle restrizioni in capo ai distributori i produttori si affidano spesso alla distribuzione diretta, vuoi per conto proprio con i propri dipendenti, vuoi attraverso agenti commerciali o tramite commissionari. Ciò significa che il rischio della distribuzione cade soltanto in capo al produttore e ciò comporta un grande vantaggio: i fornitori sono fondamentalmente svincolati dalle restrizioni del diritto antitrust e possono persino stabilire il prezzo di rivendita. Questo ha portato ad un aumento della distribuzione diretta in tutte le categorie di prodotti, compreso anche il settore automobilistico.

La grande maggioranza dei contratti stipulati online tra imprese e consumatori viene ormai conclusa mediante la sottoscrizione online del contratto e il richiamo alle condizioni generali di vendita, predisposte unilateralmente dal venditore/fornitore di servizi e consultabili sul sito web. Altrettanto usualmente, tra le condizioni generali di vendita è presente una clausola di scelta della legge applicabile al contratto, solitamente a favore della legge del luogo dove l’impresa ha sede.

La Corte di Giustizia Europea con la pronuncia C‑191/15 (VKI contro Amazon EU, 28 luglio 2016) ha precisato i requisiti di validità di una clausola di scelta di legge inserita nelle condizioni generali di un contratto B2C (“Business to Consumer”) stipulato online. La sentenza ha avuto un impatto molto rilevante nella redazione delle condizioni generali di vendita o servizio, perché la mancanza dei requisiti imposti dalla Corte di Giustizia Europea produce l’invalidità della clausola e la sua inapplicabilità in un’eventuale vertenza. È il caso, quindi, di ripercorrere la decisione della Corte di Giustizia.

Il caso sottopostole riguardava un contratto stipulato proprio con questa modalità: Amazon EU – con sede in Lussemburgo – commercia con i suoi clienti austriaci attraverso il portale amazon.de e nelle condizioni generali di vendita aveva inserito la seguente clausola: «Si applica la legge lussemburghese con esclusione delle disposizioni della Convenzione delle Nazioni Unite in materia di contratti di vendita internazionale di merci».

Su richiesta di un’associazione di consumatori, la Corte Suprema Austriaca ha chiesto alla Corte di Giustizia Europea di verificare se una simile clausola potesse essere considerata abusiva ai sensi dell’art. 3, par. 1, della direttiva 93/13 a tutela dei consumatori nei contratti stipulati con un professionista: “Una clausola contrattuale, che non è stata oggetto di negoziato individuale, si considera abusiva se, malgrado il requisito della buona fede, determina, a danno del consumatore, un significativo squilibrio dei diritti e degli obblighi delle parti derivanti dal contratto”.

La Corte ha, in primo luogo, osservato che il diritto europeo consente in linea di principio che un imprenditore inserisca nelle sue condizioni generali una clausola di scelta di legge, anche quando essa non sia stata oggetto di trattativa individuale con il consumatore. A fronte di questa possibilità, il legislatore europeo (art. 6, par. 2, Regolamento Roma I) ha previsto un meccanismo di tutela per il consumatore, garantendogli in ogni caso il diritto a invocare le disposizioni imperative della legge dello Stato in cui egli risiede, indipendentemente dalla legge individuata nella clausola. Il consumatore, quindi, anche se non previsto dalla clausola, potrà utilizzare le disposizioni inderogabili dello Stato nel quale ha la residenza abituale se più favorevoli di quelle previste dalla legge scelta nelle condizioni generali.

La Corte Europea, però, ha anche considerato essenziale che il professionista informi il consumatore del suo diritto a invocare le disposizioni di legge imperative “interne”, per evitare che quest’ultimo – ignorando l’art. 6, par. 2 del Regolamento Roma I e facendo affidamento unicamente a quanto scritto nella clausola – sia dissuaso dall’agire in giudizio nei confronti dell’imprenditore.

Questa situazione, infatti, andrebbe a creare un significativo squilibrio dei diritti e degli obblighi delle parti derivanti dal contratto, rendendo la clausola abusiva ai sensi dell’articolo 3, paragrafo 1, della direttiva 93/13.

Come dovrà quindi essere formulata una clausola di scelta di legge all’interno delle condizioni generali predisposte per un contratto B2C? La soluzione viene offerta dalla stessa Corte di Giustizia.

La clausola di scelta della legge applicabile dovrà informare il consumatore che egli può beneficiare anche della tutela consumeristica assicuratagli dalle disposizioni imperative della legge dello stato dove abitualmente risiede.

Sarà, al contrario, abusiva qualunque clausola che induca in errore il consumatore, dandogli l’impressione che al contratto si applichi soltanto la legge dello stato dove l’imprenditore/professionista ha sede.

Questa sentenza offre lo spunto per una considerazione più generale: le aziende e i professionisti che operano nel mercato e-commerce, specialmente nel settore B2C, devono prestare particolare attenzione agli sviluppi non solo della normativa interna ed europea, ma anche delle normative e delle interpretazioni giurisprudenziali nei paesi i cui risiedono i potenziali consumatori dei prodotti o servizi venduti, sia che si tratti di vendite sui canali tradizionali, sia online, al fine di evitare di predisporre dei contratti che si rivelino poco efficaci o, ancor peggio, controproducenti.

Tutte le considerazioni finora svolte non riguardano la competenza giurisdizionale e l’eventuale inserimento nel contratto di una clausola di scelta del foro competente, che nei contratti B2C è generalmente sconsigliabile. In ambito europeo, infatti, il Regolamento Bruxelles I bis accorda al consumatore una tutela molto forte, che gli dà quasi sempre la possibilità di proporre l’azione giudiziale nel luogo dove ha la sua residenza abituale (cd. Foro del consumatore), obbligando il professionista – indipendentemente da clausole con diverso contenuto – a fare lo stesso.

On February 14, 2019, the European Commission proudly announced in a press release that the night before, the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission reached a political deal on the first-ever rules aimed at creating a fair, transparent and predictable business environment for businesses and traders when using online platforms.

The new Regulation is part of the strategic plan of the European authorities to establish a digital single market and has its origin in the Commission Communication on Online Platforms of May 2016. As a result, in April 2018 the Commission presented the proposal of a new regulation.

The new rules will apply to companies such as Google AdSense, DoubleClick , eBay and Amazon Marketplace, Google and Bing Search , Facebook and YouTube, Google Play and App Store, Facebook Messenger, PayPal, Zalando and Uber.

After having conducted a series of studies, workshops and a large public consultation, the European Commission explained in its 2016 Communication the importance of creating in Europe a favorable environment for the development of new online platforms. Indeed, the statistics are very disappointing: only 4% of the world’s market capitalization is represented by online platforms created in Europe. The champions in the field are the United States and Asia.

On the basis of this observation, the Commission has drawn up a list of challenges for the European lawmaker as follows:

- Ensuring a level playing field for comparable digital services

- Ensuring that online platforms act responsibly

- Fostering trust, transparency and ensuring fairness

- Keeping markets open and non-discriminatory to foster a data-driven economy

- Safeguarding a fair and innovation-friendly business environment