-

Испания

The importance of Mediation in Distribution Contracts

14 июля 2020

- Альтернативное разрешение споров

- Распространение

Summary — The Covid-19 emergency has accelerated the transition to e-commerce, both in B2C relationships and in many B2B sectors. Many companies have found themselves operating on the Internet for the first time, shifting their business and customer relationships to the digital world. Unfortunately, it is often the case that attempts at fraud are concealed behind expressions of interest from potential customers. This is particularly the case with new business contacts from China, via email or via the company’s website or social network profiles. Let’s see what the recurrent scams are, small and large, which happen frequently, especially in the world of wine, food, design, and fashion.

What I’m talking about in this post:

- The request for products via the internet from a Chinese buyer

- The legalization of the contract in China, the signature by the Chinese notary public and other expenses

- The modification of payment terms (Man in the mail)

- The false registration of the brand or domain web

- Design and fashion: the phantom e-commerce platform

- The bitcoin and cryptocurrency trader

- How to verify the data of a Chinese company

- How we can help you

Unmissable deal or attempted fraud?

Fortunately, the bad guys in China (and not only: this kind of scams are often perpetrated also by criminals from other countries) are not very creative and the types of scams are well known and recurrent: let’s see the main ones.

The invitation to sign the contract in China

The most frequent case is that of a Chinese company that, after having found information about the foreign products through the website of the company, communicates by email the willingness to purchase large quantities of the products.

This is usually followed by an initial exchange of correspondence via email between the parties, at the outcome of which the Chinese company communicates the decision to purchase the products and asks to finalize the agreement very quickly, inviting the foreign company to go to China to conclude the negotiation and not let the deal fade away.

Many believe it and cannot resist the temptation to jump on the first plane: once landed in China the situation seems even more attractive, since the potential buyer proves to be a very surrendering negotiator, willing to accept all the conditions proposed by the foreign party and hasty to conclude the contract.

This is not a good sign, however: it must sound like a warning.

It is well known that the Chinese are skillful and very patient negotiators, and commercial negotiations are usually long and nerve-wracking: a negotiation that is too easy and fast, especially if it is the first meeting between the parties, is very suspicious.

That you are faced with an attempted scam is then certified by the request for some payments in China, allegedly necessary for the deal.

There are several variants of this first scheme.

The most common are the request to pay a fee for the registration of the contract with a Chinese notary public; a fee for administrative or customs duties; a cash payment for costs of licenses or import permits for the goods, the offer of lunches or dinners to potential business partners (at inflated prices), the stay in a hotel booked by the Chinese side, followed by the surprise of an exorbitant bill.

Back home, unfortunately, very often the signed contract will remain a useless piece of paper, the phantom client will become unavailable and the Chinese company never return the emails or calls of the foreign client. You will then have the certainty that the entire operation was designed with the sole purpose of extorting the unwary foreigner a few thousand euros.

The same scheme (i.e. the commercial order followed by a series of payment requests) can also be carried out online, for reasons similar to those indicated: the clues of the scam are always the contact by a stranger for a very high value order, a very quick negotiation with a request to conclude the deal in a short time and the need to make some payment in advance before concluding the contract.

Payment to a different bank account

Another very frequent scam is the bank account scam which is different from the one usually used.

Here the parts are usually reversed. The Chinese company is the seller of the products, from which the foreign entrepreneur intends to buy or has already bought a number of products.

One day the seller or the agent of reference informs the buyer that the bank account normally used has been blocked (the most frequent excuses are that the authorized foreign currency limit has been exceeded, or administrative checks are in progress, or simply the bank used has been changed), with an invitation to pay the price on a different current account, in the name of another person or company.

In other cases, the request is motivated by the fact that the products will be supplied through another company, which holds the export license for the products and is authorized to receive payments on behalf of the seller.

After making the payment, the foreign buyer receives the bitter surprise: the seller declares they never received the payment, that the different bank account does not belong to the company and that the request for payment to another account came from a hacker who intercepted the correspondence between the parties.

Only then, by verifying the email address from which the request for use of the new account was sent, the buyer generally sees some small difference in the email account used for the payment request on the different account (e.g. different domain name, different provider or different username).

The seller will then only be willing to ship the goods on condition that the payment is renewed on the correct bank account, which — obviously – one should not do, to avoid being deceived a second time. Verification of the owner of the false bank account generally does not lead to any response from the bank and it will in fact be impossible to identify the perpetrators of the scam.

The scam of the fake Chinese Trademark Agent

Another classic Chinese scam is the sending of an email informing the foreign company that a Chinese person intends to register a trademark or a web domain identical to that of the foreign company.

The sender is a self-proclaimed Chinese agency in the sector, which communicates its willingness to intervene and avert the danger, blocking the registration, provided that it is done in a very short time and the foreigner pay the service in advance.

In this case too we are faced with a clumsy attempt at fraud: better to trash the email immediately.

By the way: If you haven’t registered your trademark in China, you should do so right now. If you are interested in learning more about it, you can read this post.

Designers and fashion products: the phantom Chinese e- commerce platform

A widespread scam is the one involving designers and companies in the fashion industry: also in this case the contact arrives through the website or the social media account of the company and expresses a great interest in importing and distributing in China products of the Italian designer or brand.

In the cases that I have dealt with in the past, the proposal is accompanied by a substantial trademark license and distribution contract in English, which provides for the exclusive granting of the trademark and the right to sell the products in China in favor of a Chinese online platform, currently under construction, which will make it possible to reach a very large number of customers.

After signing the contract, the pretexts to extort money from the foreign company are similar to those seen previously: invitation to China and request a series of payments on site, or the need to cover a series of costs to be borne by the Chinese side to start business operations in China for the foreign company: trademark registration, customs requirements, obtaining licenses, etc. (needless to say, all fictional: the platform does not exist, nothing will be done and the contact person will vanish soon after she has received the money).

The bitcoin and cryptocurrency scam

Recently a scam of Chinese origin is the proposal to invest in bitcoin, with a very attractive guaranteed minimum return on investmen (usually 20 or 30%).

The alleged trader presents himself in these cases as a representative of an agency based in China, often referring to a purpose-built website and presentations of investment services made in English.

This scheme usually involves also an international bank, which acts as agent or depository of the sums: in reality, the writer is always the criminal organization, from a bogus account which resembles that of the bank or financial intermediary.

Once the sums are paid the broker disappears and it is not possible to trace the funds because the bank account is closed and the company disappears, or because the payments were made through bitcoin.

The clues of the scam are similar to those seen previously: contact from the Internet or via email, very tempting business proposal, hurry to conclude the agreement and to receive a first payment in China.

How to figure out if we’re dealing with an internet scam

In the cases mentioned above, and in other similar cases, once the scam has been perpetrated there is almost no point in trying to remedy it: the costs and legal fees are usually higher than the money lost and in most cases it is impossible to trace the person responsible for the scam.

Here then is some practical advice — in addition to common sense — to avoid falling into traps similar to those described

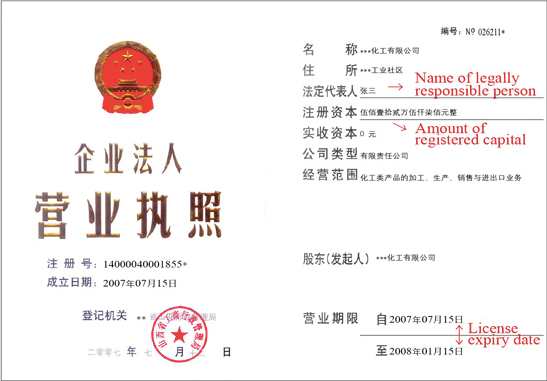

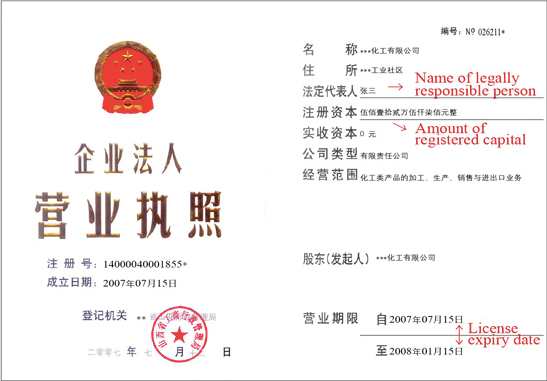

How to verify the data of a Chinese company

The name of the company in Latin characters and the website in English have no official value, they are just fancy translations: the only way to verify the data of a Chinese company, and to know the people who represent it (or say they do) is to check out the original business license through the online portal of the SAIC (State Administration for Industry and Commerce).

Each Chinese company has in fact a business license issued by SAIC, which contains the following information:

- official company name in Chinese characters;

- registration number;

- registered office;

- company object;

- date of incorporation and expiry;

- legal representative;

- registered and paid-up capital.

It is a Chinese language document, similar to the following:

Verifying the information, with the help of a competent lawyer, will make it possible to ascertain whether or not the company exists, the reliability of the company and whether the self-styled representative can actually act on behalf of the company.

Ask for commercial references

Regardless of whether the Chinese company is interested in importing Italian wine, French fashion or design or other foreign products, an easy check to do is to ask a list international companies with which the Chinese party has previously worked, to validate the information received.

In most cases, the Chinese side will oppose giving references for reasons of privacy, which confirms the suspicion that in reality such phantom success stories do not exist and this is an attempt at fraud.

Manage payments carefully

Having positively marked the first points, it is still advisable to proceed with great caution, especially in the case of a new customer or supplier.

In the case of the sale of products to a Chinese buyer, it is advisable to ask for an advance payment and for the balance of the price when the goods are ready, or the opening of a letter of credit.

In case the Chinese party is the supplier, it is recommended to provide for an on-site inspection of the goods, with a third party to certify the quality of the products and the compliance with the contractual specifications.

Verify requests to change payment methods

If a business relationship is already in progress and you are asked to change the method of payment of the price, you should carefully verify the identity and email account of the applicant and for security it is good to ask for confirmation of the instruction also through other channels of communication (writing to another person in the company, by phone or sending a message via wechat).

How we can help you

Legalmondo offers the possibility to work with a specialized lawyer to examine your need or assist you in the drafting of a contract or contract negotiations with China.

Photo by Andy Beales on Unsplash.

Summary: Since 12 July 2020, new rules apply for platform service providers and search engine operators – irrespective of whether they are established in the EU or not. The transition period has run out. This article provides checklists for platform service providers and search engine operators on how to adapt their services to the Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 on the promotion of fairness and transparency for commercial users of online intermediation services – the P2B Regulation.

The P2B Regulation applies to platform service providers and search engine operators, wherever established, provided only two conditions are met:

(i) the commercial users (for online intermediation services) or the users with a company website (for online search engines) are established in the EU; and

(ii) the users offer their goods/services to consumers located in the EU for at least part of the transaction.

Accordingly, there is a need for adaption for:

- Online intermediation services, e.g. online marketplaces, app stores, hotel and other travel booking portals, social media, and

- Online search engines.

The P2B Regulation applies to platforms in the P2B2C business in the following constellation (i.e. pure B2B platforms are exempt):

Provider -> Business -> Consumer

The article follows up on the introduction to the P2B Regulation here and the detailed analysis of mediation as method of dispute resolution here.

Checklist how to adapt the general terms and conditions of platform services

Online intermediation services must adapt their general terms and conditions – defined as (i) conditions / provisions that regulate the contractual relationship between the provider of online intermediation services and their business users and (ii) are unilaterally determined by the provider of online intermediation services.

The checklist shows the new main requirements to be observed in the general terms and conditions (“GTC”):

- Draft them in plain and intelligible language (Article 3.1 a)

- Make them easily available at any time (also before conclusion of contract) (Article 3.1 b)

- Inform on reasons for suspension / termination (Article 3.1 c)

- Inform on additional sales channels or partner programs (Article 3.1 d)

- Inform on the effects of the GTC on the IP rights of users (Article 3.1 e)

- Inform on (any!) changes to the GTC on a durable medium, user has the right of termination (Article 3.2)

- Inform on main parameters and relative importance in the ranking (incl. possible influence of remuneration), without algorithms or business secrets (Article 5.1, 5.3, 5.5)

- Inform on the type of any ancillary goods/services offered and any entitlement/condition that users offer their own goods/services (Article 6)

- Inform on possible differentiated treatment of goods / services of the provider or individual users towards other users (Article 7.1, 7.2, 7.3)

- No retroactive changes to the GTC (Article 8a)

- Inform on conditions under which users can terminate contract (Article 8b)

- Inform on available or non-available technical and contractual access to information that the Service maintains after contract termination (Article 8c)

- Inform on technical and contractual access or lack thereof for users to any data made available or generated by them or by consumers during the use of services (Article 9)

- Inform on reasons for possible restrictions on users to offer their goods/services elsewhere under other conditions («best price clause»); reasons must also be made easily available to the public (Article 10)

- Inform on access to the internal complaint-handling system (Article 11.3)

- Indicate at least two mediators for any out-of-court settlement of disputes (Article 12)

These requirements – apart from the clear, understandable language of the GTC, their availability and the fundamental ineffectiveness of retroactive adjustments to the GTC – clearly go beyond what e.g. the already strict German law on general terms and conditions requires.

Checklist how to adapt the design of platform services and search engines

In addition, online intermediation services and online search engines must adapt their design and, among other things, introduce internal complaint-handling. The checklist shows the main design requirements for:

a) Online intermediation services

- Make identity of commercial user clearly visible (Article 3.5)

- State reasons for suspension / limitation / termination of services (Article 4.1, 4.2)

- Explain possible differentiated treatment of goods / services of providers themselves or users in relation to other users (Article 7.1, 7.2, 7.3), see above

- Set an internal complaint handling system, with publicly available info, annual updates (Article 11, 4.3)

b) Online search engines

- Explain the ranking’s main parameters and their relative importance, public, easily available, always up to date (incl. possible influence of remuneration), without algorithms or trade secrets (Article 5.2, 5.3, 5.5)

- If ranking changes or delistings occur due to notification by third parties: offer to inspect such notification (Article 5.4)

- Explain possible differentiated treatment of goods / services of providers themselves or users in relation to other users (Article 7.1, 7.2, 7.3)

The European Commission will provide guidelines regarding the ranking rules in Article 5, as announced in the P2B Regulation – see the overview here. At the same time, providers of online intermediation services and online search engines shall draw up codes of conduct together with their users.

Practical Tips

- The Regulation significantly affects contractual freedom as it obliges platform services to adapt their general terms and conditions.

- The Regulation is to be enforced by «representative organisations» or associations and public bodies, with the EU Member States ensuring adequate and effective enforcement. The European Commission will monitor the impact of the Regulation in practice and evaluate it for the first time on 13.01.2022 (and every three years thereafter).

- The P2B Regulation may affect distribution relationships, in particular platforms as distribution intermediaries. Under German distribution law, platforms and other Internet intermediation services acting as authorised distributors may be entitled to a goodwill indemnity at termination (details here) if they disclose their distribution channels on the basis of corresponding platform general terms and conditions, as the Regulation does not require, but at least allows to do (see also: Rohrßen, ZVertriebsR 2019, 341, 344–346). In addition, there are numerous overlaps with antitrust, competition and data protection law.

Summary — According to French case law, an agent is subject to the protection of the commercial agent legal status and therefor is entitled to a termination indemnity only if it has the power to negotiate freely the price and terms of the sale contracts. ECJ ruled recently that such condition is not compliant with European law. However, principals could now consider other options to limit or exclude the termination indemnity.

It is an understatement to say that the ruling of the European court of justice of June 4, 2020 (n°C828/18, Trendsetteuse / DCA) was expected by both French agents and their principals.

The question asked to the ECJ

The question asked by the Paris Commercial Court on December 19, 2018 to the ECJ concerned the definition of the status of the commercial agent who could benefit from the EC Directive of December 18, 1986 and consequently of article L134 and seq. of Commercial Code.

The preliminary question consisted in submitting to the ECJ the definition adopted by the Court of Cassation and many Courts of Appeal, since 2008 : the benefit of the status of commercial agent was denied to any agent who does not have, according to the contract and de facto, the power to freely negotiate the price of sale contracts concluded, on behalf of the seller, with a buyer (this freedom of negotiation being also extend to other essential terms of the sale, such as delivery or payment terms).

The restriction ruled by French courts

This approach was criticized because, among other things, it was against the very nature of the economic and legal function of the commercial agent, who has to develop the principal’s activity while respecting its commercial policy, in a uniform manner and in strict compliance with the instructions given. As most of the agency contracts subject to French law expressly exclude the agent’s freedom to negotiate the prices or the main terms of the sales contracts, judges regularly requalified the contract from commercial agency contract into common interest mandate contract. However, this contract of common interest mandate is not governed by the provisions of Articles L 134 et seq. of the Commercial Code, many of which are of internal public order, but by the provisions of the Civil Code relating to the mandate which in general are not considered to be of public order.

The main consequence of this dichotomy of status lays in the possibility for the principal bound by a contract of common interest mandate to expressly set aside the compensation at the end of the contract, this clause being perfectly valid in such a contract, unlike to the commercial agent contract (see French Chapter to Practical Guide to International Commercial Agency Contracts).

The decision of the ECJ and its effect

The ECJ ruling of June 4, 2020 puts an end to this restrictive approach by French courts. It considers that Article 1 (2) of Directive of December 18, 1986 must be interpreted as meaning that agents must not necessarily have the power to modify the prices of the goods which they sell on behalf of a principal in order to be classified as a commercial agent.

The court reminds in particular that the European directive applies to any agent who is empowered either to negotiate or to negotiate and conclude sales contracts. The court added that the concept of negotiation cannot be understood in the restrictive lens adopted by French judges. The definition of the concept of «negotiation” must not only take into account the economic role expected from such intermediary (negotiation being very broad: i.e. dealing) but also preserve the objectives of the directive, mainly to ensure the protection of this type of intermediary.

In practice, principals will therefore no longer be able to hide behind a clause prohibiting the agent from freely negotiating the prices and terms of sales contracts to deny the status of commercial agent.

Alternative options to principals

What are the means now available to French or foreign manufacturers and traders to avoid paying compensation at the end of the agency contract?

- First of all, in case of international contracts, foreign principals will probably have more interest in submitting their contract to a foreign law (provided that it is no more protective than French law …). Although commercial agency rules are not deemed to be overriding mandatory rules by French courts (diverging from ECJ Ingmar and Unamar case law), to secure the choice not to be governed by French law, the contract should also better stipulate an exclusive jurisdiction clause to a foreign court or an arbitration clause (see French Chapter to Practical Guide to International Commercial Agency Contracts).

- it is also likely that principal will ask more often a remuneration for the contribution of its (preexisting) clients data base to the agent, the payment of this remuneration being deferred at the end of the contract … in order to compensate, if necessary, in whole or in part, with the compensation then due to the commercial agent.

- It is quite certain that agency contracts will stipulate more clearly and more comprehensively the duties of the agent that the principal considers to be essential and which violation could constitute a serious fault, excluding the right to an end-of-contract compensation. Although judges are free to assess the seriousness of a breach, they can nevertheless use the contractual provisions to identify what was important in the common intention of the parties.

- Some principals will also probably question the opportunity of continuing to use commercial agents, while in certain cases their expected economic function may be less a matter of commercial agency contract, but rather more of a promotional services contract. The distinction between these two contracts must, however, be strictly observed both in their text and in reality, and other consequences would need to be assessed, such as the regime of the prior notice (see our article on sudden termination of contracts)

Finally, the reasoning used by ECJ in this ruling (autonomous interpretation in the light of the context and aim of this directive) could possibly lead principals to question the French case-law rule consisting in granting, almost eyes shut, two years of gross commissions as a flat fee compensation, whereas article 134-12 of Commercial code does not fix the amount of this end-of-contract compensation but merely indicates that the actual damage suffered by the agent must be compensated ; so does article 17.3 of the 1986 EC directive. The question could then be asked whether such article 17.3 requires the agent to prove the damage actually suffered.

It is usually said that “conflict is not necessarily bad, abnormal, or dysfunctional; it is a fact of life[1]” I would perhaps add that quite often conflict is a suitable opportunity to evolve and to solve problems[2]. It is, in fact, a useful part of life[3] and particularly, should I add, of businesses. And conflicts not only arise at the end of the business relationship or to terminate it, but also during it and the parties remain willing to continue it.

The 2008 EU Directive on certain aspects of mediation in civil and commercial matters states that «agreements resulting from mediation are more likely to be complied with voluntarily and are more likely to preserve an amicable and sustainable relationship between the parties.»

Can, therefore, mediation be used not only as an alternative to court or arbitration when terminating distribution agreements, but also to re-organize them or to change contract conditions? Would it be useful to solve these conflicts? What could be the advantages?

In distribution/agency/franchise agreements, particularly for those lasting several years, parties can have neglected their obligations (for instance minimum sales targets not attained).

Sometimes they could have tolerated the situation although they remain not very happy with the other party’s performance because they are still doing acceptable business.

It could also happen that one of the parties wishes to restructure the entire distribution network (Can we change the distribution structure to an agency one?), but does not want to face a complete termination because there are other benefits in the relationship.

There may be just some changes to be introduced, or changes in the legal structures (A mere reseller transformed in distributor?), legal frameworks, legal conditions (Which one is the applicable law?), limitation of the scope of contract, territory…

And now, we face the Covid-19 crisis where everything is still more uncertain.

In some cases, it could happen that there is no written contract and the parties wish to draft it; in other cases, agreements could have been defectively drafted with incomplete, contradictory or no regulation at all (Was it an exclusive agreement?).

The contracts could be perfect for the situation imagined when signed several years ago but not anymore (What happen with online sales?) or circumstances, markets, services, products have changed and need to be reconsidered (mergers, change of directors…).

Sometimes, even more powerful parties have not the elements to oblige the weaker party to respect new terms, or they simply prefer not to impose their conditions, but to build up a more collaborative relationship for the future.

In all these cases, negotiation is the usual strategy parties follow: each one is focused in obtaining its own benefits with a clear idea of, for instance, which clause(s) should be modified or drafted.

Nevertheless, mediation could add some neutrality, and some space to a more efficient, structured and useful approach to the modification of the commercial relationship, particularly in distribution agreements where the collaboration (in the past, but also in the future if the parties wish so) is of paramount importance.

In most of these situations, personal emotional aspects could also be involved and make more difficult a neutral negotiation: a distributor that has been seen by the manufacturer as not performing very well and feels hurt, an agent that could consider a retirement, parties from different cultures that need to understand different ways of performing, franchisees that have been treated differently in the network and feel discriminated, etc.

In these circumstances and in other similar ones, where all persons involved, assisted by their respective lawyers, wish to continue the relationship although maybe in a different way, a sort of facilitative mediation can be a great help.

These are, in my opinion, the main reasons:

- Mediation is a legal and organized procedure that could help the parties to increase their awareness of the necessity to redraft the agreement (or drafting for the first time if it was not already done).

- Parties can be heard more easily, negotiation is eased in the interest of both of them, encourages them to act more reasonably vis-à-vis the other side, restores relationship if necessary, deadlock can be easily broken and, if the circumstances advice so, parties can be engaged separately with the help of the mediator.

- Mediation can consider other elements different to the mere commercial or legal ones: emotions linked to performance, personal situations (retirement, succession, illness) or even differences in cultural approaches.

- It helps to find the real (possibly new or not shown) interests in the commercial relationship of the parties, focusing in developments, strategies, new proposals… The mere negotiation between the parties and they attorneys could not make appear these new interests and therefore be limited only to the discussion on the change of concrete obligations, clauses or situations. Mediation helps to go beyond.

- Mediation techniques can also help the parties to face their current situation, to take responsibility of their performance without focusing on blame or incompetence but on a constructive and future collaboration in new specific terms.[4]

- It can also avoid the increasing of the conflict into a more severe one (breaching) and in case mediation does not end with a new/redrafted agreement, the basis for a mediated termination can be established, if the parties wish so, instead of litigation.

- Mediation can conclude into a new agreement where the parties are more reassured, more comfortable with, and more willing to respect because they were involved in their construction with the assistance of their respective lawyers, and because all their interests (not only new drafted clauses) were considered.

- And, in any case, mediation does not affect the party’s collaborative position and does not reduce their possibility to use other alternatives, including litigation or arbitration to terminate the agreement or to oblige the other party to respect its legal obligations.

The use of mediation does not need the parties to have foreseen it in the agreement (although it could be easier if they did so) but they can use it freely at any time.

This said, a lawyer proposing mediation as a contractual clause or, in case it was not included in the agreement, as a procedure to face this sort of conflicts in distribution agreements, will be certainly seen by his/her client as problem-solving attorney looking for the client’s interests rather than a litigator pushing them to a more uncertain situation, with unknown costs and unforeseeable timeframe.

Parties in distribution agreements should have this possibility in mind and lawyers have the opportunity to actively participate in mediation from the first steps by recommending it in the initial agreement, during the process helping the clients to express their concerns and interests, and in the drafting of the final (new) agreement, representing the clients’ and as co-author of their success.

If you would like to hear more on the topic of mediation and distribution agreements you can check out the recording of our webinar on Mediation in International Conflicts

[1] Moore, Christopher W. The Mediation Process: Practical Strategies for Resolving Conflict. Jossey-Bass. Wiley, 2014.

[2] Mnookin, Robert H. Beyond Winning. Negotiating to create value in deals and disputes (p. 53). Harvard University Press, 2000.

[3] Fisher, R; Ury, W. Getting to Yes: Negotiating an agreement without giving in. Random House.

[4] «Talking about blame distracts us from exploring why things went wrong and how we might correct them going forward. Focusing instead on understanding the contribution system allows us to learn about the real causes of the problem, and to work on correcting them.» [Stone, Douglas. “Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most”. Penguin Publishing Group]

Quick Summary: In Germany, on termination of a distribution contract, distribution intermediaries (especially distributors / franchisees) may claim an indemnity from their manufacturer / supplier if their position is similar to that of commercial agents. This is the case if the distribution intermediary is integrated into the supplier’s sales organization and obliged to transfer its customer base to the supplier, i.e. to transmit its customer data, so that the supplier can immediately and without further ado make use of the advantages of the customer base at the end of the contract. A recent court decision now aims at extending the distributor’s right to indemnity also to cases where the supplier in any way benefited from the business relationship with the distributor, even where the distributor did not provide the customer data to the supplier. This article explains the situation and gives tips on how to overcome the ambiguity that this new decision brings with it.

A German court has recently widened the distributor’s right to goodwill indemnity at termination: Suppliers might even have to pay indemnity if the distributor was not obliged to transfer the customer base to the supplier. Instead, any goodwill provided could suffice – understood as substantial benefits the supplier can, after termination, derive from the business relationship with the distributor, regardless of what the parties have stipulated in the distribution agreement.

The decision may impact all businesses where products are sold through distributors (and franchisees, see below) – particularly in retail (especially for electronics, cosmetics, jewelry, and sometimes fashion), car and wholesale trade. Distributors are self-employed, independent contractors who sell and promote the products

- on a regular basis and in their own name (differently from commercial agents),

- on their own account (differently from commission agents),

- thus bearing the sales risk, for which – in return – their margins are rather high.

Under German law, distributors are less protected than commercial agents. However, even distributors and commission agents (see here) are entitled to claim indemnity at termination if two prerequisites are given, namely if the distributor or the commission agent is

- integrated into the supplier’s sales organization (more than a pure reseller); and

- obliged (contractually or factually) to forward customer data to the supplier during or at termination of the contract (German Federal Court, 26 November 1997, Case No. VIII ZR 283/96).

Now, the Regional Court of Nuremberg-Fürth has established that the second prerequisite shall already be fulfilled if the distributor has provided the supplier with goodwill:

“… the only decisive factor, in the sense of an analogy, is whether the defendant (the principal) has benefited from the business relationship with the plaintiff (distributor). …

… the principal owes an indemnity if he has a «goodwill», i.e. a justified profit expectation, from the business relationships with customers created by the distributor.”

(Decision of 27 November 2018, Case no. 2 HK O 10103/12).

To support this wider approach, the court abstractly referred to the opinion by the EU advocate general in the case Marchon/Karaszkiewicz, rendered on 10 September 2015. That case, however, did not concern distributors, but the commercial agent’s entitlement to an indemnity, specifically the concept of “new customers” under the Commercial Agency Directive 86/653/EEC.

In the present case, it would, according to the court, suffice that the supplier had the data on the customers generated by the distributor on his computer and could freely make use of them. Other cases where the distributor indemnity might arise, even regardless of the concrete customer data, would be cases where the supplier takes over the store from the distributor, with the consequence of customers continuing to visit the very store also after the distributor has left.

Practical tips:

1. The decision makes the legal situation with distributors / franchisees less clear. The court’s wider approach needs, however, to be seen in the light of the Federal Court’s case law: The court still in 2015 denied a distributor the indemnity, arguing that the second prerequisite was missing, i.e. that the distributor was not obliged to forward the customer data (decision of 5 February 2015, case no. VII ZR 315/13, following its earlier decision re Toyota, 17 April 1996, case no. VIII ZR 5/95). Moreover, the Federal Court also denied franchisees the right to indemnity where the franchise concerns anonymous bulk business and customers continue to be regular customers only de facto (decision of 5 February 2015, case no. VII ZR 109/13 re bakery chain “Kamps”). It remains to be seen how the case law develops.

2. In any case, suppliers should, before entering the German market, consider whether they are willing to take that risk of having to pay indemnity at termination.

3. The same applies to franchisors: franchisees will likely be able to claim indemnity based on analogue application of commercial agency law. Until today, the German Federal Court of Justice has denied the franchisee’s indemnity claim in the single case and therefore left open whether franchisees in general could claim such indemnity (e.g. decision of 23 July 1997, case no. VIII ZR 134/96 re Benetton stores). Nevertheless, German courts could quite likely affirm the claim in the case of distribution franchising (where the franchisee buys the products from the franchisor), provided the situation is similar to distributorship and commercial agency. This could be the case where the franchisee has been entrusted with the distribution of the franchisor’s products and the franchisor alone is entitled, after termination of contract, to access the customers newly acquired by the franchisee during the contract (cf. German Federal Court, decision of 29 April 2010, Case No. I ZR 3/09, Joop). No indemnity, however, can be claimed where

- the franchise concerns anonymous bulk business and customers continue to be regular customers only de facto (decision of 5 February 2015 re the bakery chain “Kamps”);

- or production franchising (bottling contracts, etc.) where the franchisor or licensor is not active in the very sector of products distributed by the franchisee / licensee (decision of 29 April 2010, Case No. I ZR 3/09, Joop).

4. The German indemnity for distributors – or potentially for franchisees – can still be avoided by:

- choosing another law that does not provide for an indemnity;

- obliging the supplier to block, stop using and, if necessary, delete such customer data at termination (German Federal Court, decision of 5 February 2015, case no. VII ZR 315/13: “Subject to the provisions set out in Section [●] below, the supplier shall block the data provided by the distributor after termination of the distributor’s participation in the customer service, cease their use and delete them upon the distributor’s request.«). Though such contractual provision appears to be irrelevant according to the above decision by the Court of Nuremberg, the court does not provide any argument why the established Federal Court’s case law should not apply any more;

- explicitly contracting the indemnity out, which, however, may work only if (i) the distributor acts outside the EEA and (ii) there is no mandatory local law providing for such indemnity (see the article here).

5. Further, if the supplier deliberately accepts to pay the indemnity in return for a solid customer base with perhaps highly usable data (in compliance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation), the supplier can agree with the distributor on “entry fees” to mitigate the obligation. The payment of such entry fees or contract fees could be deferred until termination and then offset against the distributor’s claim for indemnity.

6. The distributor’s goodwill indemnity is calculated on basis of the margins made with new customers brought by the distributor or with existing customers where the distributor has significantly increased the business. The exact calculation can be quite sophisticated and German courts apply different calculation methods. In total, it may amount up to the past years’ average annual margin the distributor made with such customers.

According to the well-established jurisprudence of the Spanish Supreme Court, a distributor may be entitled to compensation for clientele if article 28 of the Agency Law is applied analogically (the «inspiring idea«). This compensation is calculated for the agent based on the remunerations received in the last five years.

In a distribution contract, however, there are no «remunerations» such as those received by the agent (commissions, fixed amounts or others), but «commercial margins» (differences between the purchase and resale price). The question is, then, what magnitude to consider for the clientele compensation in a distribution contract: either the «gross margin» (the aforementioned difference between the purchase price and the resale price), or the «net margin» (that same difference but deducing other expenses and taxes in which the distributor had incurred in).

The conclusion until now seemed to be to calculate the compensation of the distributor from his «gross margins» since this is a magnitude more comparable to the «remuneration» of the agent: other expenses and taxes of the distributor could not be deduced in the same way as in an agency contract neither expenses and taxes were deduced.

The Supreme Court (November 17, 1999) had pointed out that in order to calculate compensation for clients «it is more appropriate to consider it as a gross contribution, since with it the agent must cover all the disbursements of its commercial organization«. In addition, the «earnings obtained» «do not constitute remuneration in the same sense» (October 21, 2008), given that such «benefits«, «belong to the internal scope of the agent’s own organization» (March 12, 2012).

Recently, however, the judgment of the Supreme Court of March 1, 2017 (confirmed by another of May 19, 2017) considers that the determination of the amount of clientele compensation in a distribution contract cannot be based on the «gross margins» obtained by the distributor, but in the «net margin». To reach this conclusion, the Court refers to a judgment of the same court of 2016 and to others of 2010 and 2007.

Does this imply a change in the case-law? In my opinion, this reading that the Supreme makes is not correct. Let’s see why.

In the judgment of March 2017, the disjunctive between gross or net margin is mentioned in the Second Legal Argument and refers to the ruling of 2016.

In that judgment of 2016 it was said that although in another of 2010 it was not concluded whether the calculation had to be made on gross or net margins, in a previous one of 2007, it was admitted that what was similar to the remuneration of the agent was the net profit obtained by the distributor (profits once deduced expenses and taxes) and not the margin that is the difference between purchase and resale prices.

Now, in my opinion, in the judgment of March 2017 the Supreme Court is referring in last instance to the judgement 296/2007 for something that the latter did not say. In 2007, the Supreme Court did not quantify clientele compensation, but rather damages. More specifically, and after stating that «the compensation for customers must be requested clearly in the lawsuit, without confusion or ambiguity«, the Court concluded that the Chamber «must resolve what corresponds according to the terms in which the debate was raised…in the initial lawsuit. And since…an indemnity of damages was interested mainly based on the time that the relationship had lasted…the solution more adjusted to the jurisprudence of this Court…consists in fixing as indemnification of damages an amount equivalent to the net benefits that [were] obtained by the distribution of the products…during the year immediately prior to the termination of the contract«. Therefore, in that the judgment of 2007 the Court did not decide on clientele compensation, but on damages.

In this way, the conclusion reached in 2007 to calculate compensation for damages on net margins, was transferred without further analysis to 2016 but for the calculation of clientele compensation. This criterion is now reiterated in the judgments of 2017 almost automatically.

In my opinion, however, and despite the jurisprudential change, the thesis that should prevail is that in order to apply analogically clientele compensation in distribution contracts, the magnitude equivalent to the «remuneration» of the agent is the «gross margin» obtained by the distributor and not its «net margin»: it does not make much sense that if the analogy is applied to recognize the clientele compensation to a distributor, it is deducted from its gross margins amounts to reach its margin or net profit. The agent also has his expenses and also pays his taxes starting from his «remunerations» and nothing in Directive 86/653/EEC nor in the Agency Contract Act allows to deduce such magnitudes to calculate his clientele compensation. In my opinion, therefore, and in line with this, distributors should be equal: the magnitudes that could be compared should be the (gross) retributions of the agent with the (gross) margins of the distributor (i. e. the difference between purchase and resale price).

In conclusion, judgments of March 1 and May 19, 2017 insist on what I consider a prior mistake and generate additional confusion to an issue that has already been discussed: the analogical application of clientele compensation to the distribution contracts and the calculation method.

Updating Notice (January 27, 2020)

In a recent Order (“Auto”) of the Supreme Court of November 20, 2019 (ATS 12255/2019 of inadmissibility of an appeal), the Court has had occasion to return to this matter and to confirm the criteria of the last jurisprudence: that in the distribution contracts, the magnitude to consider to apply the analogy and calculate the goodwill indemnity are the “net margins”.

In this procedure, a distributor appealed the decision of the Provincial Court of Barcelona that recognized compensation based on net margins and not gross margins. Said distributor requested the Supreme Court to annul said judgment on the grounds that it was taken following the latest jurisprudence, erroneous according to previous one in the appellant’s opinion.

The Supreme Court, however, seems to confirm that, contrary to the thesis that I defended above in this Post, « there is no alleged error in the most recent jurisprudence in the analogical interpretation of art. 28.3 of the Agency Law for the distribution contract, nor, therefore, the need to review the most recent jurisprudence on the subject ». Consequently, if the Supreme Court does not review its latest jurisprudence and considers that the judgment that applied the net margins was acceptable, we must consider that the magnitude to be considered in the compensation for clientele in distribution contracts is that of the net margins and not gross margins

With this decision it seems (or just «its seems»?), therefore, that the Court settles the discussion that, however and in my opinion, will nevertheless continue to rise to numerous discussions.

Quick summary — Under Swiss law, a distributor may be entitled to a goodwill indemnity after termination of a distribution agreement. The Swiss Supreme Court has decided that the Swiss Code of Obligations, which provides commercial agents with an inalienable claim to a compensation for acquired customers at the end of the agency relationship, may be applied by analogy to distribution relationships under certain circumstances.

In Switzerland, distribution agreements are innominate contracts, i.e., agreements which are not specifically governed by the Swiss Code of Obligations («CO»). Distribution agreements are primarily governed by the general provisions of Swiss contract law. In addition to that, certain provisions of Swiss agency law (articles 418a et seqq. CO) may be applied by analogy to distribution relationships.

Particularly with regard to the consequences of a termination of a distribution agreement, the Swiss Supreme Court has decided in a leading case of 2008 (BGE 134 III 497) concerning an exclusive distribution agreement that article 418u CO may be applied by analogy to distribution agreements. Article 418u CO entitles commercial agents to a goodwill indemnity (sometimes also referred to as «compensation for clientele«) at the end of the agency relationship. The goodwill indemnity serves as a mean to compensate an agent for “surrendering” its customer base to the principal upon termination of the agency relationship.

The assessment whether a distributor is entitled to a goodwill indemnity consists of two stages: In a first stage, it is necessary to analyse whether the requirements stipulated by the Swiss Supreme Court for an analogous application of article 418u CO to the distribution relationship at stake are met. If so, it must be analysed, in a second stage, whether all requirements for a goodwill indemnity set forth in article 418u CO are fulfilled.

Application by analogy of article 418u CO to the distribution agreement

An analogous application of Article 418u CO to distribution agreements requires that the distributor is integrated to a large extent into the supplier’s distribution organisation. Because of such strong integration, distributors must find themselves in an agent-like position and dispose of only limited economic autonomy.

The following criteria indicate a strong integration into the supplier’s distribution organisation:

- The distributor must comply with minimum purchase obligations.

- The supplier has the right to unilaterally change prices and delivery terms.

- The supplier has the right to unilaterally terminate the manufacturing and distribution of productscovered by the agreement.

- The distributor must comply with minimum marketing expenditure obligations.

- The distributor is obliged to maintain minimum stocks of contract products.

- The distribution agreement imposes periodical reporting obligations (e.g., regarding achieved sales and activities of competitors) on the distributor.

- The supplier is entitled to inspect the distributor’s books and to conduct audits.

- The distributor is prohibited from continuing distributing the products following the end of the distribution relationship.

The more of these elements are present in a distribution agreement, the higher the chance that article 418u CO may be applied by analogy to the distribution relationship at stake. If, however, none or only a few of these elements exist, article 418u CO will most likely not be applicable and no goodwill indemnity will be due.

Requirements for an entitlement to a goodwill indemnity

In case an analogous application of article 418u CO can be affirmed, the assessment continues. It must then be analysed whether all requirements for a goodwill indemnity set forth in article 418u CO are met. In that second stage, the assessment resembles the test to be carried out for «normal» commercial agency relationships.

Applied by analogy to distribution relationships, article 418u CO entitles distributors to a goodwill indemnity in cases where four requirements are met:

- Considerable expansion of customer base by distributor

First, the distributor’s activities must have resulted in a «considerable expansion» of the supplier’s customer base. The distributor’s activities may not only include targeting specific customers, but also building up a new brand of the supplier.

Due to the limited case law available from the Swiss Supreme Court, there is legal uncertainty as to what «considerable expansion» means. Two elements seem to be predominant: on the one hand the absolute number of customers and on the other hand the turnover achieved with such customers. The customer base existing at the beginning of the distribution relationship must be compared to the customer base upon termination of the agreement. The difference must be positive.

- Supplier must continue benefitting from customer base

Second, considerable benefits must accrue to the supplier even after the end of the distribution relationship from business relations with customers acquired by the distributor. That second requirement includes two important aspects:

Firstly, the supplier must have access to the customer base, i.e., know who customers are. In agency relationships, this is usually not an issue since contracts are concluded between customers and the principal, who will therefore know about the identity of customers. In distribution relationships, however, knowledge of the supplier about the identity of customers regularly requires a disclosure of customer lists by the distributor, may it be during or at the end of the distribution relationship.

Secondly, there must be some loyalty of the customers towards the supplier, so that the supplier can continue doing business with such customers after termination of the distribution relationship. This is the case, e.g., if retailers acquired by a former wholesale distributor continue buying products directly from the supplier once the relationship with the wholesale distributor ended. Furthermore, a supplier may also continue benefitting from customers acquired by the distributor if it can make profitable after-sales business, e.g., by supplying consumables, spare parts and providing maintenance and repair services.

Swiss case law distinguishes between two different kinds of customers: personal customers and real customers. The former are linked to the distributor because of a special relationship of trust and will usually remain with the distributor once the distribution relationship comes to an end. The latter are attached to a brand or product and normally follow the supplier. In principle, only real customers may give rise to a goodwill indemnity.

The development of the supplier’s turnover after the end of a distribution relationship may serve as an indication for the loyalty of customers. A sharp downfall of the turnover and a need on the part of the supplier (or new distributor) to acquire new or re-acquire former customers suggests that customers are not loyal, so that no goodwill indemnity would be due.

- Equitability of goodwill indemnity

Third, a goodwill indemnity must not be inequitable. The following circumstances could render a goodwill indemnity inequitable:

- The distributor was able to achieve an extraordinarily high margin or received further remunerations that constitute a sufficient consideration for the value of customers passed on to the supplier.

- The distribution relationship lasted for a long time, so that the distributor already had ample opportunity to economically benefit from the acquired customers.

- In return for complying with a post-contractual non-compete obligation, the distributor receives a special compensation.

In any event, courts dispose of a considerable discretion when deciding whether a goodwill indemnity is equitable.

- Termination not caused by distributor

Fourth, the distribution relationship must not have ended for a reason attributable to the distributor.

This will notably be the case if the supplier has terminated the distribution agreement because of a reason attributable to the distributor, e.g., in case of a breach of contractual obligations or an insufficient performance by the distributor.

Furthermore, no goodwill indemnity will be due in case the distributor has terminated the distribution agreement itself, unless such termination is justified by reasons attributable to the supplier (e.g., a violation of the exclusivity granted to the distributor by the supplier).

A goodwill indemnity cannot only be due in case a distribution agreement for an indefinite period of time ended due to a notice of termination, but also in case of the expiry respectively non-renewal of a fixed-term distribution relationship.

Quantum of a goodwill indemnity

Where article 418u CO is applicable by analogy to a distribution relationship and all above-mentioned requirements for a goodwill indemnity are met, the indemnity payable to the distributor may amount up to the distributor’s net annual earnings from the distribution relationship, calculated as the average earnings of the last five years. Where the distribution relationship lasted shorter, the average earnings over the entire duration of the distribution relationship are decisive.

In order to calculate the net annual earnings, the distributor must deduct from the income obtained through the distribution relationship (e.g., gross margin, further remunerations etc.) any costs linked to its activities (e.g., marketing expenses, travel costs, salaries, rental fees etc.). A loss-making business cannot give rise to a goodwill indemnity.

In case a distributor marketed products from various suppliers, it must calculate the net annual earnings on a product-specific basis, i.e., limited to the products from the specific supplier. The distributor cannot calculate a goodwill indemnity on the basis of its business as a whole. Fixed costs must be allocated proportionally, to the extent that they cannot be assigned to a specific distribution relationship.

Mandatory nature of the entitlement to a goodwill indemnity

Suppliers regularly attempt to exclude goodwill indemnities in distribution agreements. However, if an analogous application of article 418u CO to the distribution agreement is justified and all requirements for a goodwill indemnity are met, the entitlement is mandatory and cannot be contractually excluded in advance. Any such provisions would be null and void.

Having said that, specific provisions in distribution agreements dealing with a goodwill indemnity, as, e.g., contractual provisions that address how the supplier shall compensate the distributor for acquired customers, still remain relevant. Such rules could render an entitlement to a goodwill indemnity inequitable.

Are insurers liable for breach of the GDPR on account of their appointed intermediaries?

Insurers acting out of their traditional borders through a local intermediary should choose carefully their intermediaries when distributing insurance products, and use any means at their disposal to control them properly. Distribution of insurance products through an intermediary can be a fast way to distribute insurance products and enter a territory with a minimum of investments. However, it implies a strict control of the intermediary’s activities.

The reason is that Insurers in FOS can be held jointly liable with the intermediary if this one violates personal data regulation and its obligations as set by the GDPR (Regulation 2016/679 of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data).

In a decision dated 18 July 2019 , the CNIL (Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés), the French authority in charge of personal data protection rendered a decision against ACTIVE ASSURANCE, a French intermediary, for several breaches of the GDPR. The intermediary was found guilty and fined EUR 180,000 for failing to properly protect the personal data of its clients. Those were found easily accessible on the web by any technician well versed in data processing. Moreover, the personal access codes of the clients were too simple and therefore easily accessible by third parties.

Although in this particular case insurers were not fined by the CNIL, the GDPR considers that they can be jointly liable with the intermediary in case of breach of personal data. In particular, the controller is liable for any acts of the processor he has appointed, this one being considered as a sub-contractor (clauses 24 and 28 of the GDPR).

This illustrates the risks to distribute insurance products through an intermediary without controlling its activities. Acting through intermediaries, in particular for insurance companies acting from foreign EU countries in FOS under the EU Directive on freedom of insurance services (Directive 2016/97 of 20 January 2016 on insurance distribution) requires a strict control through enacting contractual dispositions whereas are defined:

- a clear distribution of the duties between insurer and distributor (who is controller/joint controller/processor ?) as regards technical means used for protecting personal data (who shall do/control what ?) and legal requirements (who must report to the authorities in case of breach of security/ who shall reply to requests from data owners?, etc.);

- the right of the insurer to audit the distributors’ technical means used for this protection at any time during the term of the contract. In addition to this, one should always keep in mind that this audit should be conducted efficiently by the insurer at regular times. As Napoleon rightly said: “You can govern from afar, but you can only administer closely”.

Scrivi a Ignacio

Germany – Distribution, Franchise Agreements and Goodwill Indemnity at Termination

24 февраля 2020

-

Германия

- Распространение

Summary — The Covid-19 emergency has accelerated the transition to e-commerce, both in B2C relationships and in many B2B sectors. Many companies have found themselves operating on the Internet for the first time, shifting their business and customer relationships to the digital world. Unfortunately, it is often the case that attempts at fraud are concealed behind expressions of interest from potential customers. This is particularly the case with new business contacts from China, via email or via the company’s website or social network profiles. Let’s see what the recurrent scams are, small and large, which happen frequently, especially in the world of wine, food, design, and fashion.

What I’m talking about in this post:

- The request for products via the internet from a Chinese buyer

- The legalization of the contract in China, the signature by the Chinese notary public and other expenses

- The modification of payment terms (Man in the mail)

- The false registration of the brand or domain web

- Design and fashion: the phantom e-commerce platform

- The bitcoin and cryptocurrency trader

- How to verify the data of a Chinese company

- How we can help you

Unmissable deal or attempted fraud?

Fortunately, the bad guys in China (and not only: this kind of scams are often perpetrated also by criminals from other countries) are not very creative and the types of scams are well known and recurrent: let’s see the main ones.

The invitation to sign the contract in China

The most frequent case is that of a Chinese company that, after having found information about the foreign products through the website of the company, communicates by email the willingness to purchase large quantities of the products.

This is usually followed by an initial exchange of correspondence via email between the parties, at the outcome of which the Chinese company communicates the decision to purchase the products and asks to finalize the agreement very quickly, inviting the foreign company to go to China to conclude the negotiation and not let the deal fade away.

Many believe it and cannot resist the temptation to jump on the first plane: once landed in China the situation seems even more attractive, since the potential buyer proves to be a very surrendering negotiator, willing to accept all the conditions proposed by the foreign party and hasty to conclude the contract.

This is not a good sign, however: it must sound like a warning.

It is well known that the Chinese are skillful and very patient negotiators, and commercial negotiations are usually long and nerve-wracking: a negotiation that is too easy and fast, especially if it is the first meeting between the parties, is very suspicious.

That you are faced with an attempted scam is then certified by the request for some payments in China, allegedly necessary for the deal.

There are several variants of this first scheme.

The most common are the request to pay a fee for the registration of the contract with a Chinese notary public; a fee for administrative or customs duties; a cash payment for costs of licenses or import permits for the goods, the offer of lunches or dinners to potential business partners (at inflated prices), the stay in a hotel booked by the Chinese side, followed by the surprise of an exorbitant bill.

Back home, unfortunately, very often the signed contract will remain a useless piece of paper, the phantom client will become unavailable and the Chinese company never return the emails or calls of the foreign client. You will then have the certainty that the entire operation was designed with the sole purpose of extorting the unwary foreigner a few thousand euros.

The same scheme (i.e. the commercial order followed by a series of payment requests) can also be carried out online, for reasons similar to those indicated: the clues of the scam are always the contact by a stranger for a very high value order, a very quick negotiation with a request to conclude the deal in a short time and the need to make some payment in advance before concluding the contract.

Payment to a different bank account

Another very frequent scam is the bank account scam which is different from the one usually used.

Here the parts are usually reversed. The Chinese company is the seller of the products, from which the foreign entrepreneur intends to buy or has already bought a number of products.

One day the seller or the agent of reference informs the buyer that the bank account normally used has been blocked (the most frequent excuses are that the authorized foreign currency limit has been exceeded, or administrative checks are in progress, or simply the bank used has been changed), with an invitation to pay the price on a different current account, in the name of another person or company.

In other cases, the request is motivated by the fact that the products will be supplied through another company, which holds the export license for the products and is authorized to receive payments on behalf of the seller.

After making the payment, the foreign buyer receives the bitter surprise: the seller declares they never received the payment, that the different bank account does not belong to the company and that the request for payment to another account came from a hacker who intercepted the correspondence between the parties.

Only then, by verifying the email address from which the request for use of the new account was sent, the buyer generally sees some small difference in the email account used for the payment request on the different account (e.g. different domain name, different provider or different username).

The seller will then only be willing to ship the goods on condition that the payment is renewed on the correct bank account, which — obviously – one should not do, to avoid being deceived a second time. Verification of the owner of the false bank account generally does not lead to any response from the bank and it will in fact be impossible to identify the perpetrators of the scam.

The scam of the fake Chinese Trademark Agent

Another classic Chinese scam is the sending of an email informing the foreign company that a Chinese person intends to register a trademark or a web domain identical to that of the foreign company.

The sender is a self-proclaimed Chinese agency in the sector, which communicates its willingness to intervene and avert the danger, blocking the registration, provided that it is done in a very short time and the foreigner pay the service in advance.

In this case too we are faced with a clumsy attempt at fraud: better to trash the email immediately.

By the way: If you haven’t registered your trademark in China, you should do so right now. If you are interested in learning more about it, you can read this post.

Designers and fashion products: the phantom Chinese e- commerce platform

A widespread scam is the one involving designers and companies in the fashion industry: also in this case the contact arrives through the website or the social media account of the company and expresses a great interest in importing and distributing in China products of the Italian designer or brand.

In the cases that I have dealt with in the past, the proposal is accompanied by a substantial trademark license and distribution contract in English, which provides for the exclusive granting of the trademark and the right to sell the products in China in favor of a Chinese online platform, currently under construction, which will make it possible to reach a very large number of customers.

After signing the contract, the pretexts to extort money from the foreign company are similar to those seen previously: invitation to China and request a series of payments on site, or the need to cover a series of costs to be borne by the Chinese side to start business operations in China for the foreign company: trademark registration, customs requirements, obtaining licenses, etc. (needless to say, all fictional: the platform does not exist, nothing will be done and the contact person will vanish soon after she has received the money).

The bitcoin and cryptocurrency scam

Recently a scam of Chinese origin is the proposal to invest in bitcoin, with a very attractive guaranteed minimum return on investmen (usually 20 or 30%).

The alleged trader presents himself in these cases as a representative of an agency based in China, often referring to a purpose-built website and presentations of investment services made in English.

This scheme usually involves also an international bank, which acts as agent or depository of the sums: in reality, the writer is always the criminal organization, from a bogus account which resembles that of the bank or financial intermediary.

Once the sums are paid the broker disappears and it is not possible to trace the funds because the bank account is closed and the company disappears, or because the payments were made through bitcoin.

The clues of the scam are similar to those seen previously: contact from the Internet or via email, very tempting business proposal, hurry to conclude the agreement and to receive a first payment in China.

How to figure out if we’re dealing with an internet scam

In the cases mentioned above, and in other similar cases, once the scam has been perpetrated there is almost no point in trying to remedy it: the costs and legal fees are usually higher than the money lost and in most cases it is impossible to trace the person responsible for the scam.

Here then is some practical advice — in addition to common sense — to avoid falling into traps similar to those described

How to verify the data of a Chinese company

The name of the company in Latin characters and the website in English have no official value, they are just fancy translations: the only way to verify the data of a Chinese company, and to know the people who represent it (or say they do) is to check out the original business license through the online portal of the SAIC (State Administration for Industry and Commerce).

Each Chinese company has in fact a business license issued by SAIC, which contains the following information:

- official company name in Chinese characters;

- registration number;

- registered office;

- company object;

- date of incorporation and expiry;

- legal representative;

- registered and paid-up capital.

It is a Chinese language document, similar to the following:

Verifying the information, with the help of a competent lawyer, will make it possible to ascertain whether or not the company exists, the reliability of the company and whether the self-styled representative can actually act on behalf of the company.

Ask for commercial references

Regardless of whether the Chinese company is interested in importing Italian wine, French fashion or design or other foreign products, an easy check to do is to ask a list international companies with which the Chinese party has previously worked, to validate the information received.

In most cases, the Chinese side will oppose giving references for reasons of privacy, which confirms the suspicion that in reality such phantom success stories do not exist and this is an attempt at fraud.

Manage payments carefully

Having positively marked the first points, it is still advisable to proceed with great caution, especially in the case of a new customer or supplier.

In the case of the sale of products to a Chinese buyer, it is advisable to ask for an advance payment and for the balance of the price when the goods are ready, or the opening of a letter of credit.

In case the Chinese party is the supplier, it is recommended to provide for an on-site inspection of the goods, with a third party to certify the quality of the products and the compliance with the contractual specifications.

Verify requests to change payment methods

If a business relationship is already in progress and you are asked to change the method of payment of the price, you should carefully verify the identity and email account of the applicant and for security it is good to ask for confirmation of the instruction also through other channels of communication (writing to another person in the company, by phone or sending a message via wechat).

How we can help you

Legalmondo offers the possibility to work with a specialized lawyer to examine your need or assist you in the drafting of a contract or contract negotiations with China.

Photo by Andy Beales on Unsplash.

Summary: Since 12 July 2020, new rules apply for platform service providers and search engine operators – irrespective of whether they are established in the EU or not. The transition period has run out. This article provides checklists for platform service providers and search engine operators on how to adapt their services to the Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 on the promotion of fairness and transparency for commercial users of online intermediation services – the P2B Regulation.

The P2B Regulation applies to platform service providers and search engine operators, wherever established, provided only two conditions are met:

(i) the commercial users (for online intermediation services) or the users with a company website (for online search engines) are established in the EU; and

(ii) the users offer their goods/services to consumers located in the EU for at least part of the transaction.

Accordingly, there is a need for adaption for:

- Online intermediation services, e.g. online marketplaces, app stores, hotel and other travel booking portals, social media, and

- Online search engines.

The P2B Regulation applies to platforms in the P2B2C business in the following constellation (i.e. pure B2B platforms are exempt):

Provider -> Business -> Consumer

The article follows up on the introduction to the P2B Regulation here and the detailed analysis of mediation as method of dispute resolution here.

Checklist how to adapt the general terms and conditions of platform services

Online intermediation services must adapt their general terms and conditions – defined as (i) conditions / provisions that regulate the contractual relationship between the provider of online intermediation services and their business users and (ii) are unilaterally determined by the provider of online intermediation services.

The checklist shows the new main requirements to be observed in the general terms and conditions (“GTC”):

- Draft them in plain and intelligible language (Article 3.1 a)

- Make them easily available at any time (also before conclusion of contract) (Article 3.1 b)

- Inform on reasons for suspension / termination (Article 3.1 c)

- Inform on additional sales channels or partner programs (Article 3.1 d)