-

欧洲

Distribution through digital platforms | Main novelties

29 3 月 2023

- 分销协议

In this first episode of Legalmondo’s Distribution Talks series, I spoke with Ignacio Alonso, a Madrid-based lawyer with extensive experience in international commercial distribution.

Main discussion points:

- in Spain, there is no specific law for distribution agreements, which are governed by the general rules of the Commercial Code;

- therefore, it is essential to draft a clear and comprehensive contract, which will be the primary source of the parties’ rights and obligations;

- it is also good to be aware of Spanish case law on commercial distribution, which in some cases applies the law on commercial agency by analogy.

- the most common issues involving foreign producers distributing in Spain arise at the time of termination of the relationship, mainly because case law grants the terminated distributor an indemnity of clientele or goodwill if similar prerequisites to those in the agency regulations apply.

- another frequent dispute concerns the adequacy of the notice period for terminating the contract, especially if there is no agreement between the parties: the advice is to follow what the agency regulations stipulate and thus establish a minimum notice period of one month for each year of the contract’s duration, up to 6 months for agreements lasting more than five years;

- regarding dispute resolution tools, mediation is an option that should be carefully considered because it is quick, inexpensive, and allows a shared solution to be sought flexibly without disrupting the business relationship.

- if mediation fails, the parties can provide for recourse to arbitration or state court. The choice depends on the case’s specific circumstances, and one factor in favor of jurisdiction is the possibility of appeal, which is excluded in the case of arbitration.

Go deeper

- Goodwill or clientele indemnity, when it is due and how to calculate it: see this article and on our blog;

- Practical Guide on International Distribution Contract: Spain report

- Practical Guide on International Agency Contract: Spain report

- Mediation: The importance of mediation in distribution contracts

- How to negotiate and draft an international distribution agreement: 7 lessons from the history of Nike

Summary

On 1 June 2022, Regulation EU n. 720/2022, i.e.: the new Vertical Block Exemption Regulation (hereinafter: “VBER”), replaced the previous version (Regulation EU n. 330/2010), expired on 31 May 2022.

The new VBER and the new vertical guidelines (hereinafter: “Guidelines”) have received the main evidence gathered during the lifetime of the previous VBER and contain some relevant provisions affecting the discipline of all B2B agreements among businesses operating at different levels of the supply chain.

In this article, we will focus on the impact of the new VBER on sales through digital platforms, listing the main novelties impacting distribution chains, including a platform for marketing products/services.

The general discipline of vertical agreements

Article 101(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”) prohibits all agreements that prevent, restrict, or distort competition within the EU market, listing the main types, e.g.: price fixing; market partitioning; limitations on production/development/investment; unfair terms, etc.

However, Article 101(3) TFEU exempts from such restrictions the agreements that contribute to improving the EU market, to be identified in a special category Regulation.

The VBER establishes the category of vertical agreements (i.e., agreements between businesses operating at different levels of the supply chain), determining which of these agreements are exempted from Article 101(1) TFEU prohibition.

In short, vertical agreements are presumed to be exempted (and therefore valid) if they do not contain so-called “hardcore restrictions” (i.e., severe restrictions of competition, such as an absolute ban on sales in a territory or the manufacturer’s determination of the distributor’s resale price) and if neither party’s market share exceeds 30%.

The exempted agreements benefit from what has been termed the “safe harbour” of the VBER. In contrast, the others will be subject to the general prohibition of Article 101(1) TFEU unless they can benefit from an individual exemption under Article 101(3) TFUE.

The innovations introduced by the new VBER to online platforms

The first relevant aspect concerns the classification of the platforms, as the European Commission excluded that the online platform generally meets the conditions to be categorized as agency agreements.

While there have never been doubts concerning platforms that operate by purchasing and reselling products (classic example: Amazon Retail), some have arisen concerning those platforms that merely promote the products of third parties without carrying out the activity of resale (classic example: Amazon Marketplace).

With this statement, the European Commission wanted to clear the field of doubt, making explicit that intermediation service providers (such as online platforms) qualify as suppliers (as opposed to commercial agents) under the VBER. This reflects the approach of Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 (“P2B Regulation”), which has, for the first time, dictated a specific discipline for digital platforms. It provided for a set of rules to create a “fair, transparent, and predictable environment” for smaller businesses and customers” and for the rationale of the Digital Markets Act, banning certain practices used by large platforms acting as “gatekeepers”.

Therefore, all contracts concluded between manufacturers and platforms (defined as ‘providers of online intermediation services’) are subject to all the restrictions imposed by the VBER. These include the price, the territories to which or the customers to whom the intermediated goods or services may be sold, or the restrictions relating to online advertising and selling.

Thus, to give an example, the operator of a platform may not impose a fixed or minimum sale price for a transaction promoted through the platform.

The second most impactful aspect concerns hybrid platforms, i.e., competing in the relevant market to sell intermediated goods or services. Amazon is the most well-known example, as it is a provider of intermediation services (“Amazon Marketplace”), and – at the same time – it distributes the products of those parties (“Amazon Retail”). We have previously explored the distinction between those 2 business models (and the consequences in terms of intellectual property infringement) here.

The new VBER explicitly does not apply to hybrid platforms. Therefore, the agreements concluded among such platforms and manufacturers are subject to the limitations of the TFEU, as such providers may have the incentive to favour their sales and the ability to influence the outcome of competition between undertakings that use their online intermediation services.

Those agreements must be assessed individually under Article 101 of the TFEU, as they do not necessarily restrict competition within the meaning of TFEU, or they may fulfil the conditions of an individual exemption under Article 101(3) TFUE.

The third very relevant aspect concerns the parity obligations (also referred to as Most Favoured Nation Clauses, or MFNs), i.e., the contract provisions in which a seller (directly or indirectly) agrees to give the buyer the best terms it makes available to any other buyer.

Indeed, platforms’ contractual terms often contain parity obligation clauses to prevent users from offering their products/services at lower prices or on better conditions on their websites or other platforms.

The new VBER deals explicitly with parity clauses, making a distinction between clauses whose purpose is to prohibit users of a platform from selling goods or services on more favourable terms through competing platforms (so-called “wide parity clauses”), and clauses that prohibit sales on more favourable terms only in respect of channels operated directly by the users (so-called “narrow parity clauses”).

Wide parity clauses do not benefit from the VBER exemption; therefore, such obligations must be assessed individually under Article 101(3) TFEU.

On the other hand, narrow parity clauses continue to benefit from the exemption already granted by the old VBER if they do not exceed the threshold of 30% of the relevant market share set out in Article 3 of the new VBER. However, the new Guidelines warn against using overly narrow parity obligations by online platforms covering a significant share of users, stating that if there is no evidence of pro-competitive effects, the benefit of the block exemption is likely to be withdrawn.

Impact and takeaways

The new VBER entered into force on 1 June 2022 and is already applicable to agreements signed after that date. Agreements already in force on 31 May 2022 that satisfy the conditions for exemption under the current VBER but do not satisfy the requirements under the new VBER shall benefit from a one-year transitional period.

The new regime will be the playing field for all platform-driven sales over the next 12 years (the regulation expires on 31 May 2034). Currently, the rather restrictive novelties on hybrid platforms and parity obligations will likely necessitate substantial revisions to existing trade agreements.

Here, then, are some tips for managing contracts and relationships with online platforms:

- the new VBER is the right opportunity to review the existing distribution networks. The revision will have to consider not only the new regulatory limits (e.g., the ban on wide parity clauses) but also the new discipline reserved for hybrid platforms and dual distribution to coordinate the different distribution channels as efficiently as possible, by the stakes set by the new VBER and the Guidelines;

- platforms are likely to play an even greater role during the next decade; it is, therefore, essential to consider these sales channels from the outset, coordinating them with the other existing ones (retail, direct sales, distributors, etc.) to avoid jeopardizing the marketing of products or services;

- the European legislator’s attention toward platforms is growing. Looking up from the VBER, one should not forget that they are subject to a multitude of other European regulations, which are gradually regulating the sector and which must be considered when concluding contracts with platforms. The reference is not only to the recent Digital Market Act and P2B Regulation but also to the protection of IP rights on platforms, which – as we have already seen – is still an open issue.

Summary

To avoid disputes with important suppliers, it is advisable to plan purchases over the medium and long term and not operate solely on the basis of orders and order confirmations. Planning makes it possible to agree on the duration of the ‘supply agreement, minimum volumes of products to be delivered and delivery schedules, prices, and the conditions under which prices can be varied over time.

The use of a framework purchase agreement can help avoid future uncertainties and allows various options to be used to manage commodity price fluctuations depending on the type of products , such as automatic price indexing or agreement to renegotiate in the event of commodity fluctuations beyond a certain set tolerance period.

I read in a press release: “These days, the glass industry is sending wine companies new unilateral contract amendments with price changes of 20%…”

What can one do to avoid the imposition of price increases by suppliers?

- Know your rights and act in an informed manner

- Plan and organise your supply chain

Does my supplier have the right to increase prices?

If contracts have already been concluded, e.g., orders have already been confirmed by the supplier, the answer is often no.

It is not legitimate to request a price change. It is much less legitimate to communicate it unilaterally, with the threat of cancelling the order or not delivering the goods if the request is not granted.

What if he tells me it is force majeure?

That’s wrong: increased costs are not a force majeure but rather an unforeseen excessive onerousness, which hardly happens.

What if the supplier canceled the order, unilaterally increased the price, or did not deliver the goods?

He would be in breach of contract and liable to pay damages for violating his contractual obligations.

How can one avoid a tug-of-war with suppliers?

The tools are there. You have to know them and use them.

It is necessary to plan purchases in the medium term, agreeing with suppliers on a schedule in which are set out:

- the quantities of products to be ordered

- the delivery terms

- the durationof the agreement

- the pricesof the products or raw materials

- the conditions under which prices can be varied

There is a very effective instrument to do so: a framework purchase agreement.

Using a framework purchase agreement, the parties negotiate the above elements, which will be valid for the agreed period.

Once the agreement is concluded, product orders will follow, governed by the framework agreement, without the need to renegotiate the content of individual deliveries each time.

For an in-depth discussion of this contract, see this article.

- “Yes, but my suppliers will never sign it!”

Why not? Ask them to explain the reason.

This type of agreement is in the interest of both parties. It allows planning future orders and grants certainty as to whether, when, and how much the parties can change the price.

In contrast, acting without written agreements forces the parties to operate in an environment of uncertainty. Suppliers can request price increases from one day to the next and refuse supply if the changes are not accepted.

How are price changes for future supplies regulated?

Depending on the type of products or services and the raw materials or energy relevant in determining the final price, there are several possibilities.

- The first option is to index the price automatically. E.g., if the cost of a barrel of Brent oil increases/decreases by 10%, the party concerned is entitled to request a corresponding adjustment of the product’s price in all orders placed as of the following week.

- An alternative is to provide for a price renegotiation in the event of a fluctuation of the reference commodity. E.g., suppose the LME Aluminium index of the London Stock Exchange increases above a certain threshold. In that case, the interested party may request a price renegotiationfor orders in the period following the increase.

What if the parties do not agree on new prices?

It is possible to terminate the contract or refer the price determination to a third party, who would act as arbitrator and set the new prices for future orders.

Summary

The framework supply contract is an agreement that regulates a series of future sales and purchases between two parties (customer and supplier) that take place over a certain period of time. This agreement determines the main elements of future contracts such as price, product volumes, delivery terms, technical or quality specifications, and the duration of the agreement.

The framework contract is useful for ensuring continuity of supply from one or more suppliers of a certain product that is essential for planning industrial or commercial activity. While the general terms and conditions of purchase or sale are the rules that apply to all suppliers or customers of the company. The framework contract is advisable to be concluded with essential suppliers for the continuity of business activity, in general or in relation to a particular project.

What I am talking about in this article:

- What is the supply framework agreement?

- What is the function of the supply framework agreement?

- The difference with the general conditions of sale or purchase

- When to enter a purchase framework agreement?

- When is it beneficial to conclude a sales framework agreement?

- The content of the supply framework agreement

- Price revision clause and hardship

- Delivery terms in the supply framework agreement

- The Force Majeure clause in international sales contracts

- International sales: applicable law and dispute resolution arrangements

What is a framework supply agreement?

It is an agreement that regulates a series of future sales and purchases between two parties (customer and supplier), which will take place over a certain period.

It is therefore referred to as a “framework agreement” because it is an agreement that establishes the rules of a future series of sales and purchase contracts, determining their primary elements (such as the price, the volumes of products to be sold and purchased, the delivery terms of the products, and the duration of the contract).

After concluding the framework agreement, the parties will exchange orders and order confirmations, entering a series of autonomous sales contracts without re-discussing the covenants already defined in the framework agreement.

Depending on one’s point of view, this agreement is also called a sales framework agreement (if the seller/supplier uses it) or a purchasing framework agreement (if the customer proposes it).

What is the function of the framework supply agreement?

It is helpful to arrange a framework agreement in all cases where the parties intend to proceed with a series of purchases/sales of products over time and are interested in giving stability to the commercial agreement by determining its main elements.

In particular, the purchase framework agreement may be helpful to a company that wishes to ensure continuity of supply from one or more suppliers of a specific product that is essential for planning its industrial or commercial activity (raw material, semi-finished product, component).

By concluding the framework agreement, the company can obtain, for example, a commitment from the supplier to supply a particular minimum volume of products, at a specific price, with agreed terms and technical specifications, for a certain period.

This agreement is also beneficial, at the same time, to the seller/supplier, which can plan sales for that period and organize, in turn, the supply chain that enables it to procure the raw materials and components necessary to produce the products.

What is the difference between a purchase or sales framework agreement and the general terms and conditions?

Whereas the framework agreement is an agreement that is used with one or more suppliers for a specific product and a certain time frame, determining the essential elements of future contracts, the general purchase (or sales) conditions are the rules that apply to all the company’s suppliers (or customers).

The first agreement, therefore, is negotiated and defined on a case-by-case basis. At the same time, the general conditions are prepared unilaterally by the company, and the customers or suppliers (depending on whether they are sales or purchase conditions) adhere to and accept that the general conditions apply to the individual order and/or future contracts.

The two agreements might also co-exist: in that case; it is a good idea to specify which contract should prevail in the event of a discrepancy between the different provisions (usually, this hierarchy is envisaged, ranging from the special to the general: order – order confirmation; framework agreement; general terms and conditions of purchase).

When is it important to conclude a purchase framework agreement?

It is beneficial to conclude this agreement when dealing with a mono-supplier or a supplier that would be very difficult to replace if it stopped selling products to the purchasing company.

The risks one aims to avoid or diminish are so-called stock-outs, i.e., supply interruptions due to the supplier’s lack of availability of products or because the products are available, but the parties cannot agree on the delivery time or sales price.

Another result that can be achieved is to bind a strategic supplier for a certain period by agreeing that it will reserve an agreed share of production for the buyer on predetermined terms and conditions and avoid competition with offers from third parties interested in the products for the duration of the agreement.

When is it helpful to conclude a sales framework agreement?

This agreement allows the seller/supplier to plan sales to a particular customer and thus to plan and organize its production and logistical capacity for the agreed period, avoiding extra costs or delays.

Planning sales also makes it possible to correctly manage financial obligations and cash flows with a medium-term vision, harmonizing commitments and investments with the sales to one’s customers.

What is the content of the supply framework agreement?

There is no standard model of this agreement, which originated from business practice to meet the requirements indicated above.

Generally, the agreement provides for a fixed period (e.g., 12 months) in which the parties undertake to conclude a series of purchases and sales of products, determining the price and terms of supply and the main covenants of future sales contracts.

The most important clauses are:

- the identification of products and technical specifications (often identified in an annex)

- the minimum/maximum volume of supplies

- the possible obligation to purchase/sell a minimum/maximum volume of products

- the schedule of supplies

- the delivery times

- the determination of the price and the conditions for its possible modification (see also the next paragraph)

- impediments to performance (Force Majeure)

- cases of Hardship

- penalties for delay or non-performance or for failure to achieve the agreed volumes

- the hierarchy between the framework agreement and the orders and any other contracts between the parties

- applicable law and dispute resolution (especially in international agreements)

How to handle price revision in a supply contract?

A crucial clause, especially in times of strong fluctuations in the prices of raw materials, transport, and energy, is the price revision clause.

In the absence of an agreement on this issue, the parties bear the risk of a price increase by undertaking to respect the conditions initially agreed upon; except in exceptional cases (where the fluctuation is strong, affects a short period, and is caused by unforeseeable events), it isn’t straightforward to invoke the supervening excessive onerousness, which allows renegotiating the price, or the contract to be terminated.

To avoid the uncertainty generated by price fluctuations, it is advisable to agree in the contract on the mechanisms for revising the price (e.g., automatic indexing following the quotation of raw materials). The so-called Hardship or Excessive Onerousness clause establishes what price fluctuation limits are accepted by the parties and what happens if the variations go beyond these limits, providing for the obligation to renegotiate the price or the termination of the contract if no agreement is reached within a certain period.

How to manage delivery terms in a supply agreement?

Another fundamental pact in a medium to long-term supply relationship concerns delivery terms. In this case, it is necessary to reconcile the purchaser’s interest in respecting the agreed dates with the supplier’s interest in avoiding claims for damages in the event of a delay, especially in the case of sales requiring intercontinental transport.

The first thing to be clarified in this regard concerns the nature of delivery deadlines: are they essential or indicative? In the first case, the party affected has the right to terminate (i.e., wind up) the agreement in the event of non-compliance with the term; in the second case, due diligence, information, and timely notification of delays may be required, whereas termination is not a remedy that may be automatically invoked in the event of a delay.

A useful instrument in this regard is the penalty clause: with this covenant, it is established that for each day/week/month of delay, a sum of money is due by way of damages in favor of the party harmed by the delay.

If quantified correctly and not excessively, the penalty is helpful for both parties because it makes it possible to predict the damages that may be claimed for the delay, quantifying them in a fair and determined sum. Consequently, the seller is not exposed to claims for damages related to factors beyond his control. At the same time, the buyer can easily calculate the compensation for the delay without the need for further proof.

The same mechanism, among other things, may be adopted to govern the buyer’s delay in accepting delivery of the goods.

Finally, it is a good idea to specify the limit of the penalty (e.g.,10 percent of the price of the goods) and a maximum period of grace for the delay, beyond which the party concerned is entitled to terminate the contract by retaining the penalty.

The Force Majeure clause in international sales contracts

A situation that is often confused with excessive onerousness, but is, in fact, quite different, is that of Force Majeure, i.e., the supervening impossibility of performance of the contractual obligation due to any event beyond the reasonable control of the party affected, which could not have been reasonably foreseen and the effects of which cannot be overcome by reasonable efforts.

The function of this clause is to set forth clearly when the parties consider that Force Majeure may be invoked, what specific events are included (e.g., a lock-down of the production plant by order of the authority), and what are the consequences for the parties’ obligations (e.g., suspension of the obligation for a certain period, as long as the cause of impossibility of performance lasts, after which the party affected by performance may declare its intention to dissolve the contract).

If the wording of this clause is general (as is often the case), the risk is that it will be of little use; it is also advisable to check that the regulation of force majeure complies with the law applicable to the contract (here an in-depth analysis indicating the regime provided for by 42 national laws).

Applicable law and dispute resolution clauses

Suppose the customer or supplier is based abroad. In that case, several significant differences must be borne in mind: the first is the agreement’s language, which must be intelligible to the foreign party, therefore usually in English or another language familiar to the parties, possibly also in two languages with parallel text.

The second issue concerns the applicable law, which should be expressly indicated in the agreement. This subject matter is vast, and here we can say that the decision on the applicable law must be made on a case-by-case basis, intentionally: in fact, it is not always convenient to recall the application of the law of one’s own country.

In most international sales contracts, the 1980 Vienna Convention on the International Sale of Goods (“CISG”) applies, a uniform law that is balanced, clear, and easy to understand. Therefore, it is not advisable to exclude it.

Finally, in a supply framework agreement with an international supplier, it is important to identify the method of dispute resolution: no solution fits all. Choosing a country’s jurisdiction is not always the right decision (indeed, it can often prove counterproductive).

Summary

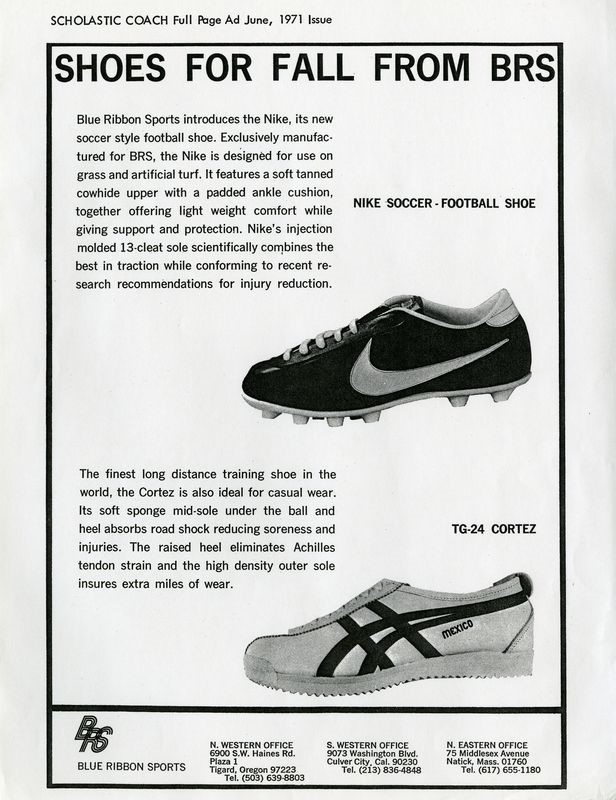

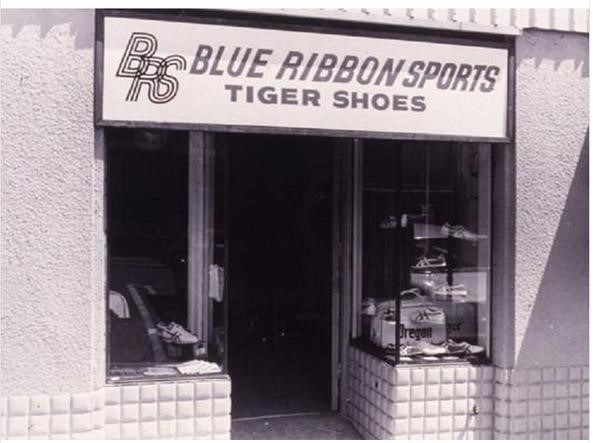

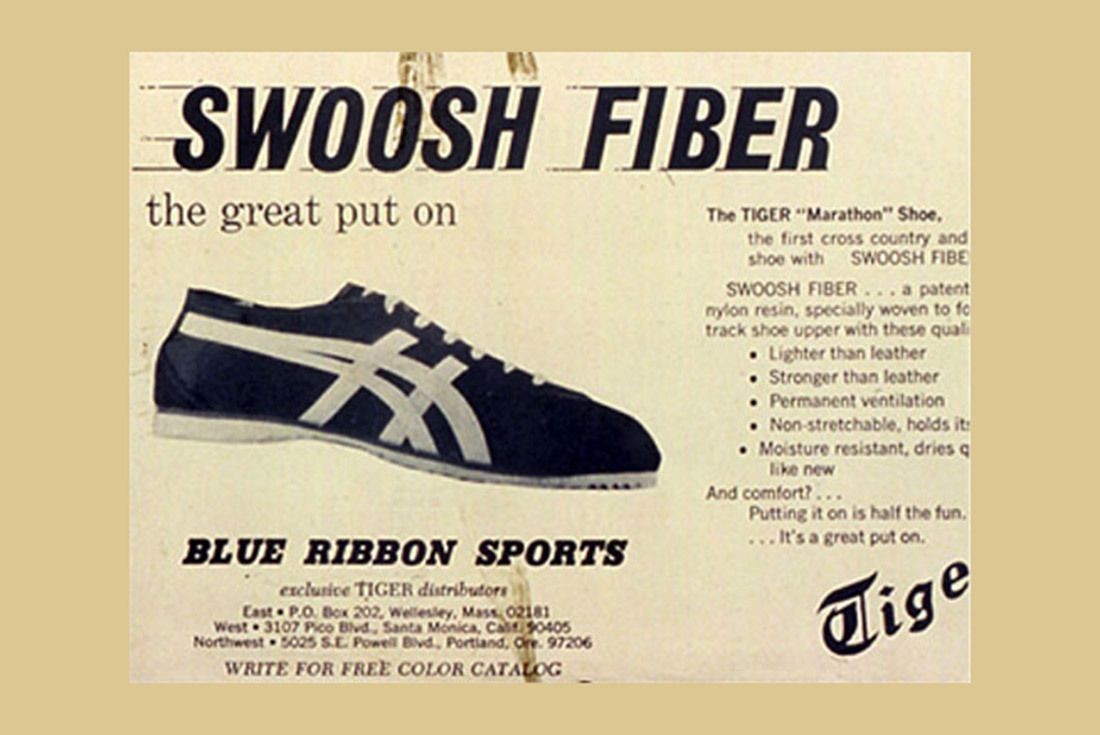

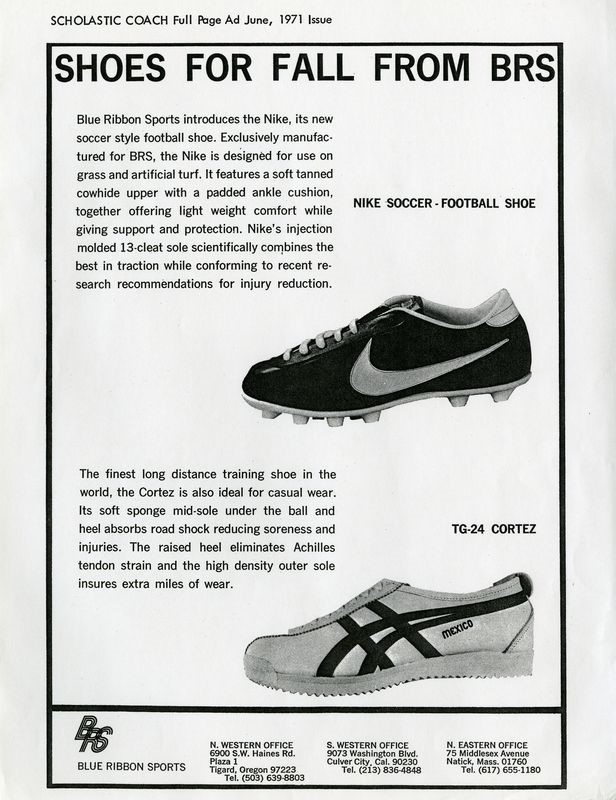

Phil Knight, the founder of Nike, imported the Japanese brand Onitsuka Tiger into the US market in 1964 and quickly gained a 70% share. When Knight learned Onitsuka was looking for another distributor, he created the Nike brand. This led to two lawsuits between the two companies, but Nike eventually won and became the most successful sportswear brand in the world. This article looks at the lessons to be learned from the dispute, such as how to negotiate an international distribution agreement, contractual exclusivity, minimum turnover clauses, duration of the contract, ownership of trademarks, dispute resolution clauses, and more.

What I talk about in this article

- The Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger dispute and the birth of Nike

- How to negotiate an international distribution agreement

- Contractual exclusivity in a commercial distribution agreement

- Minimum Turnover clauses in distribution contracts

- Duration of the contract and the notice period for termination

- Ownership of trademarks in commercial distribution contracts

- The importance of mediation in international commercial distribution agreements

- Dispute resolution clauses in international contracts

- How we can help you

The Blue Ribbon vs Onitsuka Tiger dispute and the birth of Nike

Why is the most famous sportswear brand in the world Nike and not Onitsuka Tiger?

Shoe Dog is the biography of the creator of Nike, Phil Knight: for lovers of the genre, but not only, the book is really very good and I recommend reading it.

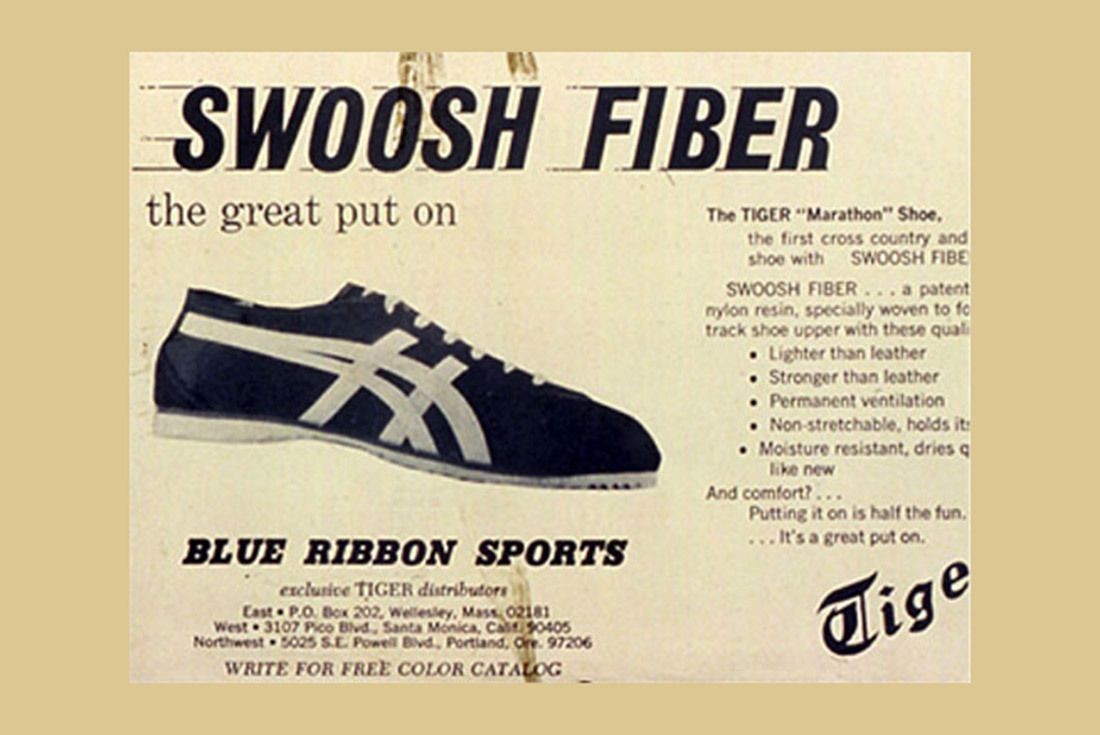

Moved by his passion for running and intuition that there was a space in the American athletic shoe market, at the time dominated by Adidas, Knight was the first, in 1964, to import into the U.S. a brand of Japanese athletic shoes, Onitsuka Tiger, coming to conquer in 6 years a 70% share of the market.

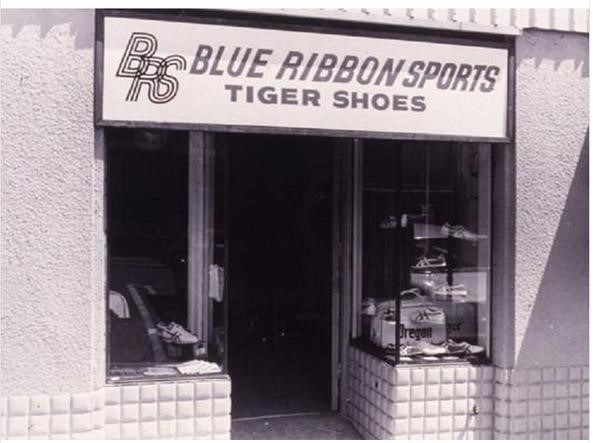

The company founded by Knight and his former college track coach, Bill Bowerman, was called Blue Ribbon Sports.

The business relationship between Blue Ribbon-Nike and the Japanese manufacturer Onitsuka Tiger was, from the beginning, very turbulent, despite the fact that sales of the shoes in the U.S. were going very well and the prospects for growth were positive.

When, shortly after having renewed the contract with the Japanese manufacturer, Knight learned that Onitsuka was looking for another distributor in the U.S., fearing to be cut out of the market, he decided to look for another supplier in Japan and create his own brand, Nike.

Upon learning of the Nike project, the Japanese manufacturer challenged Blue Ribbon for violation of the non-competition agreement, which prohibited the distributor from importing other products manufactured in Japan, declaring the immediate termination of the agreement.

In turn, Blue Ribbon argued that the breach would be Onitsuka Tiger’s, which had started meeting other potential distributors when the contract was still in force and the business was very positive.

This resulted in two lawsuits, one in Japan and one in the U.S., which could have put a premature end to Nike’s history.

Fortunately (for Nike) the American judge ruled in favor of the distributor and the dispute was closed with a settlement: Nike thus began the journey that would lead it 15 years later to become the most important sporting goods brand in the world.

Let’s see what Nike’s history teaches us and what mistakes should be avoided in an international distribution contract.

How to negotiate an international commercial distribution agreement

In his biography, Knight writes that he soon regretted tying the future of his company to a hastily written, few-line commercial agreement at the end of a meeting to negotiate the renewal of the distribution contract.

What did this agreement contain?

The agreement only provided for the renewal of Blue Ribbon’s right to distribute products exclusively in the USA for another three years.

It often happens that international distribution contracts are entrusted to verbal agreements or very simple contracts of short duration: the explanation that is usually given is that in this way it is possible to test the commercial relationship, without binding too much to the counterpart.

This way of doing business, though, is wrong and dangerous: the contract should not be seen as a burden or a constraint, but as a guarantee of the rights of both parties. Not concluding a written contract, or doing so in a very hasty way, means leaving without clear agreements fundamental elements of the future relationship, such as those that led to the dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger: commercial targets, investments, ownership of brands.

If the contract is also international, the need to draw up a complete and balanced agreement is even stronger, given that in the absence of agreements between the parties, or as a supplement to these agreements, a law with which one of the parties is unfamiliar is applied, which is generally the law of the country where the distributor is based.

Even if you are not in the Blue Ribbon situation, where it was an agreement on which the very existence of the company depended, international contracts should be discussed and negotiated with the help of an expert lawyer who knows the law applicable to the agreement and can help the entrepreneur to identify and negotiate the important clauses of the contract.

Territorial exclusivity, commercial objectives and minimum turnover targets

The first reason for conflict between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger was the evaluation of sales trends in the US market.

Onitsuka argued that the turnover was lower than the potential of the U.S. market, while according to Blue Ribbon the sales trend was very positive, since up to that moment it had doubled every year the turnover, conquering an important share of the market sector.

When Blue Ribbon learned that Onituska was evaluating other candidates for the distribution of its products in the USA and fearing to be soon out of the market, Blue Ribbon prepared the Nike brand as Plan B: when this was discovered by the Japanese manufacturer, the situation precipitated and led to a legal dispute between the parties.

The dispute could perhaps have been avoided if the parties had agreed upon commercial targets and the contract had included a fairly standard clause in exclusive distribution agreements, i.e. a minimum sales target on the part of the distributor.

In an exclusive distribution agreement, the manufacturer grants the distributor strong territorial protection against the investments the distributor makes to develop the assigned market.

In order to balance the concession of exclusivity, it is normal for the producer to ask the distributor for the so-called Guaranteed Minimum Turnover or Minimum Target, which must be reached by the distributor every year in order to maintain the privileged status granted to him.

If the Minimum Target is not reached, the contract generally provides that the manufacturer has the right to withdraw from the contract (in the case of an open-ended agreement) or not to renew the agreement (if the contract is for a fixed term) or to revoke or restrict the territorial exclusivity.

In the contract between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger, the agreement did not foresee any targets (and in fact the parties disagreed when evaluating the distributor’s results) and had just been renewed for three years: how can minimum turnover targets be foreseen in a multi-year contract?

In the absence of reliable data, the parties often rely on predetermined percentage increase mechanisms: +10% the second year, + 30% the third, + 50% the fourth, and so on.

The problem with this automatism is that the targets are agreed without having available the real data on the future trend of product sales, competitors’ sales and the market in general, and can therefore be very distant from the distributor’s current sales possibilities.

For example, challenging the distributor for not meeting the second or third year’s target in a recessionary economy would certainly be a questionable decision and a likely source of disagreement.

It would be better to have a clause for consensually setting targets from year to year, stipulating that targets will be agreed between the parties in the light of sales performance in the preceding months, with some advance notice before the end of the current year. In the event of failure to agree on the new target, the contract may provide for the previous year’s target to be applied, or for the parties to have the right to withdraw, subject to a certain period of notice.

It should be remembered, on the other hand, that the target can also be used as an incentive for the distributor: it can be provided, for example, that if a certain turnover is achieved, this will enable the agreement to be renewed, or territorial exclusivity to be extended, or certain commercial compensation to be obtained for the following year.

A final recommendation is to correctly manage the minimum target clause, if present in the contract: it often happens that the manufacturer disputes the failure to reach the target for a certain year, after a long period in which the annual targets had not been reached, or had not been updated, without any consequences.

In such cases, it is possible that the distributor claims that there has been an implicit waiver of this contractual protection and therefore that the withdrawal is not valid: to avoid disputes on this subject, it is advisable to expressly provide in the Minimum Target clause that the failure to challenge the failure to reach the target for a certain period does not mean that the right to activate the clause in the future is waived.

The notice period for terminating an international distribution contract

The other dispute between the parties was the violation of a non-compete agreement: the sale of the Nike brand by Blue Ribbon, when the contract prohibited the sale of other shoes manufactured in Japan.

Onitsuka Tiger claimed that Blue Ribbon had breached the non-compete agreement, while the distributor believed it had no other option, given the manufacturer’s imminent decision to terminate the agreement.

This type of dispute can be avoided by clearly setting a notice period for termination (or non-renewal): this period has the fundamental function of allowing the parties to prepare for the termination of the relationship and to organize their activities after the termination.

In particular, in order to avoid misunderstandings such as the one that arose between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger, it can be foreseen that during this period the parties will be able to make contact with other potential distributors and producers, and that this does not violate the obligations of exclusivity and non-competition.

In the case of Blue Ribbon, in fact, the distributor had gone a step beyond the mere search for another supplier, since it had started to sell Nike products while the contract with Onitsuka was still valid: this behavior represents a serious breach of an exclusivity agreement.

A particular aspect to consider regarding the notice period is the duration: how long does the notice period have to be to be considered fair? In the case of long-standing business relationships, it is important to give the other party sufficient time to reposition themselves in the marketplace, looking for alternative distributors or suppliers, or (as in the case of Blue Ribbon/Nike) to create and launch their own brand.

The other element to be taken into account, when communicating the termination, is that the notice must be such as to allow the distributor to amortize the investments made to meet its obligations during the contract; in the case of Blue Ribbon, the distributor, at the express request of the manufacturer, had opened a series of mono-brand stores both on the West and East Coast of the U.S.A..

A closure of the contract shortly after its renewal and with too short a notice would not have allowed the distributor to reorganize the sales network with a replacement product, forcing the closure of the stores that had sold the Japanese shoes up to that moment.

Generally, it is advisable to provide for a notice period for withdrawal of at least 6 months, but in international distribution contracts, attention should be paid, in addition to the investments made by the parties, to any specific provisions of the law applicable to the contract (here, for example, an in-depth analysis for sudden termination of contracts in France) or to case law on the subject of withdrawal from commercial relations (in some cases, the term considered appropriate for a long-term sales concession contract can reach 24 months).

Finally, it is normal that at the time of closing the contract, the distributor is still in possession of stocks of products: this can be problematic, for example because the distributor usually wishes to liquidate the stock (flash sales or sales through web channels with strong discounts) and this can go against the commercial policies of the manufacturer and new distributors.

In order to avoid this type of situation, a clause that can be included in the distribution contract is that relating to the producer’s right to repurchase existing stock at the end of the contract, already setting the repurchase price (for example, equal to the sale price to the distributor for products of the current season, with a 30% discount for products of the previous season and with a higher discount for products sold more than 24 months previously).

Trademark Ownership in an International Distribution Agreement

During the course of the distribution relationship, Blue Ribbon had created a new type of sole for running shoes and coined the trademarks Cortez and Boston for the top models of the collection, which had been very successful among the public, gaining great popularity: at the end of the contract, both parties claimed ownership of the trademarks.

Situations of this kind frequently occur in international distribution relationships: the distributor registers the manufacturer’s trademark in the country in which it operates, in order to prevent competitors from doing so and to be able to protect the trademark in the case of the sale of counterfeit products; or it happens that the distributor, as in the dispute we are discussing, collaborates in the creation of new trademarks intended for its market.

At the end of the relationship, in the absence of a clear agreement between the parties, a dispute can arise like the one in the Nike case: who is the owner, producer or distributor?

In order to avoid misunderstandings, the first advice is to register the trademark in all the countries in which the products are distributed, and not only: in the case of China, for example, it is advisable to register it anyway, in order to prevent third parties in bad faith from taking the trademark (for further information see this post on Legalmondo).

It is also advisable to include in the distribution contract a clause prohibiting the distributor from registering the trademark (or similar trademarks) in the country in which it operates, with express provision for the manufacturer’s right to ask for its transfer should this occur.

Such a clause would have prevented the dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger from arising.

The facts we are recounting are dated 1976: today, in addition to clarifying the ownership of the trademark and the methods of use by the distributor and its sales network, it is advisable that the contract also regulates the use of the trademark and the distinctive signs of the manufacturer on communication channels, in particular social media.

It is advisable to clearly stipulate that the manufacturer is the owner of the social media profiles, of the content that is created, and of the data generated by the sales, marketing and communication activity in the country in which the distributor operates, who only has the license to use them, in accordance with the owner’s instructions.

In addition, it is a good idea for the agreement to establish how the brand will be used and the communication and sales promotion policies in the market, to avoid initiatives that may have negative or counterproductive effects.

The clause can also be reinforced with the provision of contractual penalties in the event that, at the end of the agreement, the distributor refuses to transfer control of the digital channels and data generated in the course of business.

Mediation in international commercial distribution contracts

Another interesting point offered by the Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger case is linked to the management of conflicts in international distribution relationships: situations such as the one we have seen can be effectively resolved through the use of mediation.

This is an attempt to reconcile the dispute, entrusted to a specialized body or mediator, with the aim of finding an amicable agreement that avoids judicial action.

Mediation can be provided for in the contract as a first step, before the eventual lawsuit or arbitration, or it can be initiated voluntarily within a judicial or arbitration procedure already in progress.

The advantages are many: the main one is the possibility to find a commercial solution that allows the continuation of the relationship, instead of just looking for ways for the termination of the commercial relationship between the parties.

Another interesting aspect of mediation is that of overcoming personal conflicts: in the case of Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka, for example, a decisive element in the escalation of problems between the parties was the difficult personal relationship between the CEO of Blue Ribbon and the Export manager of the Japanese manufacturer, aggravated by strong cultural differences.

The process of mediation introduces a third figure, able to dialogue with the parts and to guide them to look for solutions of mutual interest, that can be decisive to overcome the communication problems or the personal hostilities.

For those interested in the topic, we refer to this post on Legalmondo and to the replay of a recent webinar on mediation of international conflicts.

Dispute resolution clauses in international distribution agreements

The dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger led the parties to initiate two parallel lawsuits, one in the US (initiated by the distributor) and one in Japan (rooted by the manufacturer).

This was possible because the contract did not expressly foresee how any future disputes would be resolved, thus generating a very complicated situation, moreover on two judicial fronts in different countries.

The clauses that establish which law applies to a contract and how disputes are to be resolved are known as “midnight clauses“, because they are often the last clauses in the contract, negotiated late at night.

They are, in fact, very important clauses, which must be defined in a conscious way, to avoid solutions that are ineffective or counterproductive.

How we can help you

The construction of an international commercial distribution agreement is an important investment, because it sets the rules of the relationship between the parties for the future and provides them with the tools to manage all the situations that will be created in the future collaboration.

It is essential not only to negotiate and conclude a correct, complete and balanced agreement, but also to know how to manage it over the years, especially when situations of conflict arise.

Legalmondo offers the possibility to work with lawyers experienced in international commercial distribution in more than 60 countries: write us your needs.

Eventually, after more than 30 years of negotiations, the world is now looking at the first pan-African trade agreement, which entered into force in 2019: the African Continental Free Trade Area, or AfCFTA.

Africa, with its 55 countries and around 1.3 billion inhabitants, is the second largest continent in the world after Asia. The continent’s potential is huge: more than 50% of Africa’s population is under 20 years old and the population is growing at the fastest rate in the world. By 2050, one in four new-born babies is expected to be African. In addition, the continent is rich in fertile soil and raw materials.

For Western investors, Africa has become considerably more important in recent years. As a result, a considerable amount of international trade has emerged, not least promoted by the “Compact with Africa” initiative adopted by the G20 countries in 2017, also known as the “Marshall Plan with Africa”. Its focus is on expanding Africa’s economic cooperation with the G20 countries by strengthening private investment.

At the same time, however, intra-African trade has stagnated so far: partly still existing high intra-African tariffs, non-tariff barriers (NTBs), weak infrastructure, corruption, cumbersome bureaucracy, as well as non-transparent and inconsistent regulations, ensured that interregional exports could hardly develop and most recently accounted for only 17 % of the pan-African trade and only 0.36 % of world trade. It’s already been a long time since the African Union (AU) had put the creation of a common trade area on its agenda.

What is behind AfCFTA?

The establishment of a pan-African trade area was preceded by decades of negotiations, which finally resulted in the entry into force of the AfCFTA on 30 May 2019.

AfCFTA is a free trade area established by its members, which – with the exception of Eritrea – covers the entire African continent and is thus the largest free trade area in the world by number of member states after the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

How the common market was to be structured in detail was the subject of several individual negotiations, which were discussed in Phases I and II.

Phase I comprises the negotiations on three protocols and is almost completed.

The Protocol on Trade in Goods

This protocol provides for the elimination of 90 % of all intra-African tariffs in all product categories within five years of entry into force. Of these, up to 7 % of products can be classified as sensitive goods, which are subject to a tariff elimination period of ten years. For the least developed countries (LDCs), the preparation period is extended from five to ten years and for sensitive products from ten to thirteen years, provided they demonstrate their need. The remaining 3 % of tariffs are fully exempted from tariff dismantling.

A prerequisite for tariff dismantling is the clear delimitation of rules of origin. Otherwise, imports from third countries could benefit from the negotiated tariff advantages. Agreement has already been reached on most of the rules of origin.

The Protocol on Trade in Services

The AU General Assembly has so far agreed on five priority areas (transport, communications, tourism, financial and business services) and guidelines for the commitments applicable to them. 47 AU member states have so far submitted their offers for specific commitments and the review of 28 has been completed. In addition, negotiations, for example, on the recognition of professional qualifications, are still ongoing.

The Protocol on Dispute Settlement

With the Protocol on Rules and Procedures Governing the Dispute Settlement, the AfCFTA creates a dispute settlement system modelled on the WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding. Under this, the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) administers the AfCFTA Dispute Settlement Protocol and establishes an Adjudicating Panel (Panel) and an Appellate Body (AB). The DSB is composed of a representative of each member state and intervenes as soon as there are differences of opinion between the contracting states on the interpretation and/or application of the agreement with regard to their rights and obligations.

For the remaining Phase II, negotiations are planned on investment and competition policy, intellectual property issues, online trade and women and youth in trade, the results of which will be reflected in further protocols.

The implementation of the AfCFTA

In principle, the implementation of trade under a trade agreement can only begin once the legal framework has been finally clarified. However, AU Heads of State and Government agreed in December 2020 that trade can begin for goods for which negotiations have been finalised. Under this “transitional arrangement“, after a pandemic-related postponement, the first AfCFTA trade settlement from Ghana to South Africa took place on 4 January 2021.

Building blocks of the AfCFTA

All 55 members of the AU were involved in the AfCFTA negotiations. Of these, 47 belong to at least one – and some to more than one – recognised Regional Economic Communities (RECs), which, according to the preamble of the AfCFTA agreement, are to continue as building blocks of the trade agreement. It was therefore they who acted as the voice of their respective members in the AfCFTA negotiations. The AfCFTA provides for RECs to retain their legal instruments, institutions and dispute settlement mechanisms.

Within the AU, there are eight recognised RECs, overlapping in some countries, which are either preferential trade agreements (Free Trade Agreements – FTAs) or customs unions.

Under the AfCFTA, the RECs have various responsibilities. These are in particular:

- coordinating negotiating positions and assisting member states in the implementation of the agreement.

- solution-oriented mediation in the event of disagreements between member states

- supporting member states in the harmonisation of tariffs and other border protection regulations

- promoting the use of the AfCFTA notification procedure to reduce NTBs

Outlook of the AfCFTA

The AfCFTA has the potential to facilitate Africa’s integration into the global economy and creates the real possibility of a realignment of international integration and cooperation patterns.

A trade agreement alone is no guarantee of economic success. For the agreement to achieve the predicted breakthrough, member states must have the political will to implement the new rules consistently and create the necessary capacity to do so. In particular, the short-term removal of trade barriers and the creation of a sustainable physical and digital infrastructure are likely to be crucial.

If you are interested in the AfCFTA, you can read an extended version of this article here.

The Legalmondo Africa Desk

We help companies invest and do business in Africa with our experts in Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, Senegal, Sudan, Egypt, Ghana, Lybia, Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, and Malawi.

We can also assist foreign entities in African countries where we are not directly present with an office through our network of local partners.

How it works

- We set up a meeting (in person or online) with one of our experts to understand the client’s needs.

- Once we start working together, we follow the client with a dedicated counsel for all its legal needs (single cases, or ongoing legal assistance)

Get in touch to know more.

Summary

Political, environmental or health crises (like the Covid-19 outbreak and the attack of Ukraine by the Russian army) can cause an increase in the price of raw materials and components and generalized inflation. Both suppliers and distributors find themselves faced with problems related to the often sudden and very substantial increase in the price of their own supplies. French law lays down specific rules in that regard.

Two main situations can be distinguished: where the parties have just established a simple flow of orders and where the parties have concluded a framework agreement fixing firm prices for a fixed term.

Price increase in a business relationship

The situation is as follows: the parties have not concluded a framework agreement, each sales contract concluded (each order) is governed by the General T&Cs of the supplier; the latter has not undertaken to maintain the prices for a minimum period and applies the prices of the current tariff.

In principle, the supplier can modify its prices at any time by sending a new tariff. However, it must give written and reasonable notice in accordance with the provisions of Article L. 442-1.II of the Commercial Code, before the price increase comes into effect. Failure to respect sufficient notice, it could be accused of a sudden “partial” termination of commercial relations (and subject to damages).

A sudden termination following a price increase would be characterized when the following conditions are met:

- the commercial relationship must be established: broader concept than the simple contract, taking into account the duration but also the importance and the regularity of the exchanges between the parties;

- the price increase must be assimilated to a rupture: it is mainly the size of the price increase (+1%, 10% or 25%?) that will lead a judge to determine whether the increase constitutes a “partial” termination (in the event of a substantial modification of the relationship which is nevertheless maintained) or a total termination (if the increase is such that it involves a termination of the relationship) or if it does not constitute a termination (if the increase is minimal);

- the notice granted is insufficient by comparing the duration of the notice actually granted with that of the notice in accordance with Article L. 442-1.II, taking into account in particular the duration of the commercial relationship and the possible dependence of the victim of the termination with respect to the other party.

Article L. 442-1.II must be respected as soon as French law applies to the relation. In international business relations, to know how to deal with Article L.442-1.II and conflicts of laws and jurisdiction of competent courts, please see our previous article published on Legalmondo blog.

Price increase in a framework contract

If the parties have concluded a framework contract (such as supply, manufacturing, …) for several years and the supplier has committed to fixed prices, how, in this case, can it change these prices?

In addition to any indexation clause or renegotiation (hardship) clause which would be stipulated in the contract (and besides specific legal provisions applicable to special agreements as to their nature or economic sector), the supplier may seek to avail himself of the legal mechanism of “unforeseeability” provided for by article 1195 of the civil code.

Three prerequisites must be cumulatively met:

- an unforeseeable change in circumstances at the time of the conclusion of the contract (i.e.: the parties could not reasonably anticipate this upheaval);

- a performance of the contract that has become excessively onerous (i.e.: beyond the simple difficulty, the upheaval must cause a disproportionate imbalance);

- the absence of acceptance of these risks by the debtor of the obligation when concluding the contract.

The implementation of this mechanism must stick to the following steps:

- first, the party in difficulty must request the renegotiation of the contract from its co-contracting party;

- then, in the event of failure of the negotiation or refusal to negotiate by the other party, the parties can (i) agree together on the termination of the contract, on the date and under the conditions that they determine, or (ii) ask together the competent judge to adapt it;

- finally, in the absence of agreement between the parties on one of the two aforementioned options, within a reasonable time, the judge, seized by one of the parties, may revise the contract or terminate it, on the date and under the conditions that he will set.

The party wishing to implement this legal mechanism must also anticipate the following points:

- article 1195 of the Civil Code only applies to contracts concluded on or after October 1, 2016 (or renewed after this date). Judges do not have the power to adapt or rebalance contracts concluded before this date;

- this provision is not of public order. Therefore, the parties can exclude it or modify its conditions of application and/or implementation (the most common being the framework of the powers of the judge);

- during the renegotiation, the supplier must continue to sell at the initial price because, unlike force majeure, unforeseen circumstances do not lead to the suspension of compliance with the obligations.

Key takeaways:

- analyse carefully the framework of the commercial relationship before deciding to notify a price increase, in order to identify whether the prices are firm for a minimum period and the contractual levers for renegotiation;

- correctly anticipate the length of notice that must be given to the partner before the entry into force of the new pricing conditions, depending on the length of the relationship and the degree of dependence;

- document the causes of the price increase;

- check if and how the legal mechanism of unforeseeability has been amended or excluded by the framework contract or the General T&Cs;

- consider alternatives strategies, possibly based on stopping production/delivery justified by a force majeure event or on the significant imbalance of the contractual provisions.

Under French Law, franchisors and distributors are subject to two kinds of pre-contractual information obligations: each party has to spontaneously inform his future partner of any information which he knows is decisive for his consent. In addition, for certain contracts – i.e franchise agreement – there is a duty to disclose a limited amount of information in a document. These pre-contractual obligations are mandatory. Thus these two obligations apply simultaneously to the franchisor, distributor or dealer when negotiating a contract with a partner.

General duty of disclosure for all contractors

What is the scope of this pre-contractual information?

This obligation is imposed on all co-contractors, to any kind of contract. Indeed, article 1112-1 of the Civil Code states that:

(§. 1) The party who knows information of decisive importance for the consent of the other party must inform the other party if the latter legitimately ignores this information or trusts its co-contractor.

(§. 3) Of decisive importance is the information that is directly and necessarily related to the content of the contract or the quality of the parties. »

This obligation applies to all contracting parties for any type of contract.

Who must prove the compliance with such provision ?

The burden of proof rests on the person who claims that the information was due to him. He must then prove (i) that the other party owed him the information but (ii) did not provide it (Article 1112-1 (§. 4) of the Civil Code)

Special duty of disclosure for franchise and distribution agreements

Which contracts are subject to this special rule?

French law requires (art. L.330-3 French Commercial Code) communication of a pre-contractual information document (in French “DIP”) and the draft contract, by any person:

- which grants another person the right to use a trade mark, trade name or sign,

- while requiring an exclusive or quasi-exclusive commitment for the exercise of its activity (e.g. exclusive purchase obligation).

Concretely, DIP must be provided, for example, to the franchisee, distributor, dealer or licensee of a brand, by its franchisor, supplier or licensor as soon as the two above conditions are met.

When the DIP must be provided?

DIP and draft contract must be provided at least 20 days before signing the contract, and, where applicable, before the payment of the sum required to be paid prior to the signature of the contract (for a reservation).

What information must be disclosed in the DIP?

Article R. 330-1 of the French Commercial Code requires that DIP mentions the following information (non-detailed list) concerning:

- Franchisor (identity and experience of the managers, career path, etc.);

- Franchisor’s business (in particular creation date, head office, bank accounts, historical of the development of the business, annual accounts, etc.);

- Operating network (members list with indication of signing date of contracts, establishments list offering the same products/services in the area of the planned activity, number of members having ceased to be part of the network during the year preceding the issue of the DIP with indication of the reasons for leaving, etc.);

- Trademark licensed (date of registration, ownership and use);

- General state of the market (about products or services covered by the contract)and local state of the market (about the planned area) and information relating to factors of competition and development perspective;

- Essential element of the draft contract and at least: its duration, contract renewal conditions, termination and assignment conditions and scope of exclusivities;

- Financial obligations weighing in on contracting party: nature and amount of the expenses and investments that will have to be incurred before starting operations (up-front entry fee, installation costs, etc.).

How to prove the disclosure of information?

The burden of proof for the delivery of the DIP rests on the debtor of this obligation: the franchisor (Cass. Com., 7 July 2004, n°02-15.950). The ideal for the franchisor is to have the franchisee sign and date his DIP on the day it is delivered and to keep the proof thereof.

The clause of contract indicating that the franchisee acknowledges having received a complete DIP does not provide proof of the delivery of a complete DIP (Cass. com, 10 January 2018, n° 15-25.287).

Sanction for breach of pre-contractual information duties

Criminal sanction

Failing to comply with the obligations relating to the DIP, franchisor or supplier can be sentenced to a criminal fine of up to 1,500 euros and up to 3,000 euros in the event of a repeat offence, the fine being multiplied by five for legal entities (article R.330-2 French commercial Code).

Cancellation of the contract for deceit

The contract may be declared null and void in case of breach of either article 1112-1 or article L. 330-3. In both cases, failure to comply with the obligation to provide information is sanctioned if the applicant demonstrates that his or her consent has been vitiated by error, deceit or violence. Where applicable, the parties must return to the state they were in before the contract.

Regarding deceit, Courts strictly assess its two conditions which are:

- (a material element) the existence of a lie or deceptive reticence (article 1137 French Civil Code);

- And (an intentional element) the intention to deceive his co-contractor (article 1130 French Civil Code).

Damages

Although the claims for contract cancellation are subject to very strict conditions, it remains that franchisees/distributors may alternatively obtain damages on the basis of tort liability for non-compliance with the pre-contractual information obligation, subject to proof of fault (incomplete or incorrect information), damage (loss of chance of not contracting or contracting on more advantageous terms) and the causal link between the two.

French case law

Franchisee/distributor must demonstrate that he would not have actually entered into the contract if he had had the missing or correct information

Courts reject motion for cancellation of a franchise contract when the franchisee cannot prove that this deceit would have misled its consent or that it would not have entered into the contract if it had had such information (for instance: Versailles Court of Appeal, December 3, 2020, no. 19/01184).

The significant experience of the franchisee/distributor greatly mitigates the possible existence of a defect in consent.

In a ruling of January 20, 2021 (no. 19/03382) the Paris Court of Appeal rejected an application for cancellation of a franchise contract where the franchisor had submitted a DIP manifestly and deliberately deficient and an overly optimistic turnover forecast.

Thus, while the presentation of the national market was not updated and too vague and that of the local market was just missing, the Court rejected the legal qualification of the franchisee’s error or the franchisor’s willful misrepresentation, because the franchisee “had significant experience” for several years in the same sector (See another example for a Master franchisee)

Similarly, the Court reminds that “An error concerning the profitability of the concept of a franchise cannot lead to the nullity of the contract for lack of consent of the franchisee if it does not result from data established and communicated by the franchisor“, it does not accept the error resulting from the communication by the franchisor of a very optimistic turnover forecast tripling in three years. Indeed, according to the Court, “the franchisee’s knowledge of the local market was likely to enable it to put the franchisor’s exaggerations into perspective, at least in part. The franchisee was well aware that the forecast document provided by the franchisor had no contractual value and did not commit the franchisor to the announced results. It was in fact the franchisee’s responsibility to conduct its own market research, so that if the franchisee misunderstood the profitability of the operation at the business level, this error was not caused by information prepared and communicated by the franchisor“.

The path is therefore narrow for the franchisee: he cannot invoke error concerning profitability when it is him who draws up his plan, and even when this plan is drawn up by the franchisor or based on information drawn up and transmitted by the franchisor, the experience of the franchisee who knew the local market may exonerate the franchisor.

Takeaways

- The information required by the DIP must be fully completed and updated ;

- The information not required by the DIP but communicated by the franchisor must be carefully selected and sincere;

- Franchisee must be given the opportunity to request additional information from the franchisor;

- Franchisee’s experience in the economic sector enables the franchisor to considerably limit its exposure to the risk of contract cancellation due to a defect in the franchisee’s consent;

- Franchisor must keep the proof of the actual disclosure of pre-contractual information (whether mandatory or not).

写信给 Giuliano

How to manage price changes in the supply chain

27 3 月 2023

-

意大利

- 契约

- 分销协议

In this first episode of Legalmondo’s Distribution Talks series, I spoke with Ignacio Alonso, a Madrid-based lawyer with extensive experience in international commercial distribution.

Main discussion points:

- in Spain, there is no specific law for distribution agreements, which are governed by the general rules of the Commercial Code;

- therefore, it is essential to draft a clear and comprehensive contract, which will be the primary source of the parties’ rights and obligations;

- it is also good to be aware of Spanish case law on commercial distribution, which in some cases applies the law on commercial agency by analogy.

- the most common issues involving foreign producers distributing in Spain arise at the time of termination of the relationship, mainly because case law grants the terminated distributor an indemnity of clientele or goodwill if similar prerequisites to those in the agency regulations apply.

- another frequent dispute concerns the adequacy of the notice period for terminating the contract, especially if there is no agreement between the parties: the advice is to follow what the agency regulations stipulate and thus establish a minimum notice period of one month for each year of the contract’s duration, up to 6 months for agreements lasting more than five years;

- regarding dispute resolution tools, mediation is an option that should be carefully considered because it is quick, inexpensive, and allows a shared solution to be sought flexibly without disrupting the business relationship.

- if mediation fails, the parties can provide for recourse to arbitration or state court. The choice depends on the case’s specific circumstances, and one factor in favor of jurisdiction is the possibility of appeal, which is excluded in the case of arbitration.

Go deeper

- Goodwill or clientele indemnity, when it is due and how to calculate it: see this article and on our blog;

- Practical Guide on International Distribution Contract: Spain report

- Practical Guide on International Agency Contract: Spain report

- Mediation: The importance of mediation in distribution contracts

- How to negotiate and draft an international distribution agreement: 7 lessons from the history of Nike

Summary

On 1 June 2022, Regulation EU n. 720/2022, i.e.: the new Vertical Block Exemption Regulation (hereinafter: “VBER”), replaced the previous version (Regulation EU n. 330/2010), expired on 31 May 2022.

The new VBER and the new vertical guidelines (hereinafter: “Guidelines”) have received the main evidence gathered during the lifetime of the previous VBER and contain some relevant provisions affecting the discipline of all B2B agreements among businesses operating at different levels of the supply chain.

In this article, we will focus on the impact of the new VBER on sales through digital platforms, listing the main novelties impacting distribution chains, including a platform for marketing products/services.

The general discipline of vertical agreements

Article 101(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”) prohibits all agreements that prevent, restrict, or distort competition within the EU market, listing the main types, e.g.: price fixing; market partitioning; limitations on production/development/investment; unfair terms, etc.

However, Article 101(3) TFEU exempts from such restrictions the agreements that contribute to improving the EU market, to be identified in a special category Regulation.

The VBER establishes the category of vertical agreements (i.e., agreements between businesses operating at different levels of the supply chain), determining which of these agreements are exempted from Article 101(1) TFEU prohibition.

In short, vertical agreements are presumed to be exempted (and therefore valid) if they do not contain so-called “hardcore restrictions” (i.e., severe restrictions of competition, such as an absolute ban on sales in a territory or the manufacturer’s determination of the distributor’s resale price) and if neither party’s market share exceeds 30%.

The exempted agreements benefit from what has been termed the “safe harbour” of the VBER. In contrast, the others will be subject to the general prohibition of Article 101(1) TFEU unless they can benefit from an individual exemption under Article 101(3) TFUE.

The innovations introduced by the new VBER to online platforms

The first relevant aspect concerns the classification of the platforms, as the European Commission excluded that the online platform generally meets the conditions to be categorized as agency agreements.

While there have never been doubts concerning platforms that operate by purchasing and reselling products (classic example: Amazon Retail), some have arisen concerning those platforms that merely promote the products of third parties without carrying out the activity of resale (classic example: Amazon Marketplace).

With this statement, the European Commission wanted to clear the field of doubt, making explicit that intermediation service providers (such as online platforms) qualify as suppliers (as opposed to commercial agents) under the VBER. This reflects the approach of Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 (“P2B Regulation”), which has, for the first time, dictated a specific discipline for digital platforms. It provided for a set of rules to create a “fair, transparent, and predictable environment” for smaller businesses and customers” and for the rationale of the Digital Markets Act, banning certain practices used by large platforms acting as “gatekeepers”.

Therefore, all contracts concluded between manufacturers and platforms (defined as ‘providers of online intermediation services’) are subject to all the restrictions imposed by the VBER. These include the price, the territories to which or the customers to whom the intermediated goods or services may be sold, or the restrictions relating to online advertising and selling.

Thus, to give an example, the operator of a platform may not impose a fixed or minimum sale price for a transaction promoted through the platform.

The second most impactful aspect concerns hybrid platforms, i.e., competing in the relevant market to sell intermediated goods or services. Amazon is the most well-known example, as it is a provider of intermediation services (“Amazon Marketplace”), and – at the same time – it distributes the products of those parties (“Amazon Retail”). We have previously explored the distinction between those 2 business models (and the consequences in terms of intellectual property infringement) here.

The new VBER explicitly does not apply to hybrid platforms. Therefore, the agreements concluded among such platforms and manufacturers are subject to the limitations of the TFEU, as such providers may have the incentive to favour their sales and the ability to influence the outcome of competition between undertakings that use their online intermediation services.

Those agreements must be assessed individually under Article 101 of the TFEU, as they do not necessarily restrict competition within the meaning of TFEU, or they may fulfil the conditions of an individual exemption under Article 101(3) TFUE.

The third very relevant aspect concerns the parity obligations (also referred to as Most Favoured Nation Clauses, or MFNs), i.e., the contract provisions in which a seller (directly or indirectly) agrees to give the buyer the best terms it makes available to any other buyer.

Indeed, platforms’ contractual terms often contain parity obligation clauses to prevent users from offering their products/services at lower prices or on better conditions on their websites or other platforms.