-

中国

China – Changes to Company Law

30 1 月 2024

- 公司法

Summary:

The heavily amended PRC Company Law will take effect on July 1, 2024. Please find below a summary of some of the important novelties embodied by this amended Company Law, which may have a significant impact on the rights and duties of the shareholders and management of a limited liability company (“LLC”).

The businesses active in the PRC may be interested in carefully reviewing their corporate documents (including the Articles of Association) in light of the amended Company Law and deciding necessary adaptive measures for compliance/optimization purposes during the transition period leading to the effective date of the said amended Company law.

Capital contribution.

The amended Company Law provides that the subscribed capital of an LLC shall be paid up as per its Articles of Association within a time period up to 5 years from its incorporation (NB: The previous law does not set a time limit for the capital contribution.). This requirement will retroactively apply to the companies incorporated prior to July 1st, 2024.

Despite the foregoing, a creditor or the company shall be entitled to request the shareholder(s) concerned to accelerate its/their capital contribution ahead of the due date for capital contribution should the company be unable to settle due debt(s) with its own assets.

The equity and credit may be used for the capital contribution.

Duties of directors/senior managers

The directors shall bear the obligation to form the “liquidation team,” which shall proceed with the liquidation within 15 days of the occurrence of a number of statutory circumstances substantiated in Article 229 of the Company Law. The directors shall be held liable for losses incurred by the company or creditor(s) arising from their failure to fulfill the above liquidation obligation on time.

The director(s)/senior manager(s) shall be held liable (along with the company itself) for compensating others should they cause any damages to the latter due to their intentional acts or gross negligence in the course of performing their duties.

The board of directors of an LLC shall regularly check the status of capital contributions by the shareholders. It shall cause the company to issue written reminders to the shareholder(s) failing to make capital contributions on time. Should the shareholder fail to honor its subscribed capital contribution despite the reminder, subject to a specific board resolution and a written notification with immediate effect, the company may declare that the shareholder is disqualified from making the capital contribution.

Corporate governance

An LLC may set up an “audit commission” composed of directors to exercise the function of supervisor or supervisors’ committee as per its Articles of Association. In such cases, the company may no longer need to set up separate supervisors’ committees or appoint supervisors.

However, the board of directors of an LLC having more than 300 employees shall have employees’ representative(s) elected through the democratic process unless the same LLC has a Supervisors’ Committee in place and such Committee already has the employees’ representative(s).

Summary – The Covid-19 emergency has accelerated the transition to e-commerce, both in B2C relationships and in many B2B sectors. Many companies have found themselves operating on the Internet for the first time, shifting their business and customer relationships to the digital world. Unfortunately, it is often the case that attempts at fraud are concealed behind expressions of interest from potential customers. This is particularly the case with new business contacts from China, via email or via the company’s website or social network profiles. Let’s see what the recurrent scams are, small and large, which happen frequently, especially in the world of wine, food, design, and fashion.

What I’m talking about in this post:

- The request for products via the internet from a Chinese buyer

- The legalization of the contract in China, the signature by the Chinese notary public and other expenses

- The modification of payment terms (Man in the mail)

- The false registration of the brand or domain web

- Design and fashion: the phantom e-commerce platform

- The bitcoin and cryptocurrency trader

- How to verify the data of a Chinese company

- How we can help you

Unmissable deal or attempted fraud?

Fortunately, the bad guys in China (and not only: this kind of scams are often perpetrated also by criminals from other countries) are not very creative and the types of scams are well known and recurrent: let’s see the main ones.

The invitation to sign the contract in China

The most frequent case is that of a Chinese company that, after having found information about the foreign products through the website of the company, communicates by email the willingness to purchase large quantities of the products.

This is usually followed by an initial exchange of correspondence via email between the parties, at the outcome of which the Chinese company communicates the decision to purchase the products and asks to finalize the agreement very quickly, inviting the foreign company to go to China to conclude the negotiation and not let the deal fade away.

Many believe it and cannot resist the temptation to jump on the first plane: once landed in China the situation seems even more attractive, since the potential buyer proves to be a very surrendering negotiator, willing to accept all the conditions proposed by the foreign party and hasty to conclude the contract.

This is not a good sign, however: it must sound like a warning.

It is well known that the Chinese are skillful and very patient negotiators, and commercial negotiations are usually long and nerve-wracking: a negotiation that is too easy and fast, especially if it is the first meeting between the parties, is very suspicious.

That you are faced with an attempted scam is then certified by the request for some payments in China, allegedly necessary for the deal.

There are several variants of this first scheme.

The most common are the request to pay a fee for the registration of the contract with a Chinese notary public; a fee for administrative or customs duties; a cash payment for costs of licenses or import permits for the goods, the offer of lunches or dinners to potential business partners (at inflated prices), the stay in a hotel booked by the Chinese side, followed by the surprise of an exorbitant bill.

Back home, unfortunately, very often the signed contract will remain a useless piece of paper, the phantom client will become unavailable and the Chinese company never return the emails or calls of the foreign client. You will then have the certainty that the entire operation was designed with the sole purpose of extorting the unwary foreigner a few thousand euros.

The same scheme (i.e. the commercial order followed by a series of payment requests) can also be carried out online, for reasons similar to those indicated: the clues of the scam are always the contact by a stranger for a very high value order, a very quick negotiation with a request to conclude the deal in a short time and the need to make some payment in advance before concluding the contract.

Payment to a different bank account

Another very frequent scam is the bank account scam which is different from the one usually used.

Here the parts are usually reversed. The Chinese company is the seller of the products, from which the foreign entrepreneur intends to buy or has already bought a number of products.

One day the seller or the agent of reference informs the buyer that the bank account normally used has been blocked (the most frequent excuses are that the authorized foreign currency limit has been exceeded, or administrative checks are in progress, or simply the bank used has been changed), with an invitation to pay the price on a different current account, in the name of another person or company.

In other cases, the request is motivated by the fact that the products will be supplied through another company, which holds the export license for the products and is authorized to receive payments on behalf of the seller.

After making the payment, the foreign buyer receives the bitter surprise: the seller declares they never received the payment, that the different bank account does not belong to the company and that the request for payment to another account came from a hacker who intercepted the correspondence between the parties.

Only then, by verifying the email address from which the request for use of the new account was sent, the buyer generally sees some small difference in the email account used for the payment request on the different account (e.g. different domain name, different provider or different username).

The seller will then only be willing to ship the goods on condition that the payment is renewed on the correct bank account, which – obviously – one should not do, to avoid being deceived a second time. Verification of the owner of the false bank account generally does not lead to any response from the bank and it will in fact be impossible to identify the perpetrators of the scam.

The scam of the fake Chinese Trademark Agent

Another classic Chinese scam is the sending of an email informing the foreign company that a Chinese person intends to register a trademark or a web domain identical to that of the foreign company.

The sender is a self-proclaimed Chinese agency in the sector, which communicates its willingness to intervene and avert the danger, blocking the registration, provided that it is done in a very short time and the foreigner pay the service in advance.

In this case too we are faced with a clumsy attempt at fraud: better to trash the email immediately.

By the way: If you haven’t registered your trademark in China, you should do so right now. If you are interested in learning more about it, you can read this post.

Designers and fashion products: the phantom Chinese e- commerce platform

A widespread scam is the one involving designers and companies in the fashion industry: also in this case the contact arrives through the website or the social media account of the company and expresses a great interest in importing and distributing in China products of the Italian designer or brand.

In the cases that I have dealt with in the past, the proposal is accompanied by a substantial trademark license and distribution contract in English, which provides for the exclusive granting of the trademark and the right to sell the products in China in favor of a Chinese online platform, currently under construction, which will make it possible to reach a very large number of customers.

After signing the contract, the pretexts to extort money from the foreign company are similar to those seen previously: invitation to China and request a series of payments on site, or the need to cover a series of costs to be borne by the Chinese side to start business operations in China for the foreign company: trademark registration, customs requirements, obtaining licenses, etc. (needless to say, all fictional: the platform does not exist, nothing will be done and the contact person will vanish soon after she has received the money).

The bitcoin and cryptocurrency scam

Recently a scam of Chinese origin is the proposal to invest in bitcoin, with a very attractive guaranteed minimum return on investmen (usually 20 or 30%).

The alleged trader presents himself in these cases as a representative of an agency based in China, often referring to a purpose-built website and presentations of investment services made in English.

This scheme usually involves also an international bank, which acts as agent or depository of the sums: in reality, the writer is always the criminal organization, from a bogus account which resembles that of the bank or financial intermediary.

Once the sums are paid the broker disappears and it is not possible to trace the funds because the bank account is closed and the company disappears, or because the payments were made through bitcoin.

The clues of the scam are similar to those seen previously: contact from the Internet or via email, very tempting business proposal, hurry to conclude the agreement and to receive a first payment in China.

How to figure out if we’re dealing with an internet scam

In the cases mentioned above, and in other similar cases, once the scam has been perpetrated there is almost no point in trying to remedy it: the costs and legal fees are usually higher than the money lost and in most cases it is impossible to trace the person responsible for the scam.

Here then is some practical advice – in addition to common sense – to avoid falling into traps similar to those described

How to verify the data of a Chinese company

The name of the company in Latin characters and the website in English have no official value, they are just fancy translations: the only way to verify the data of a Chinese company, and to know the people who represent it (or say they do) is to check out the original business license through the online portal of the SAIC (State Administration for Industry and Commerce).

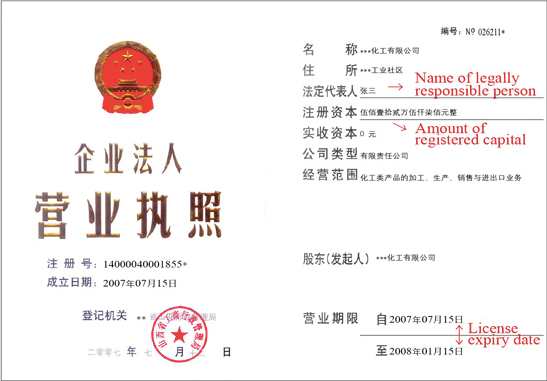

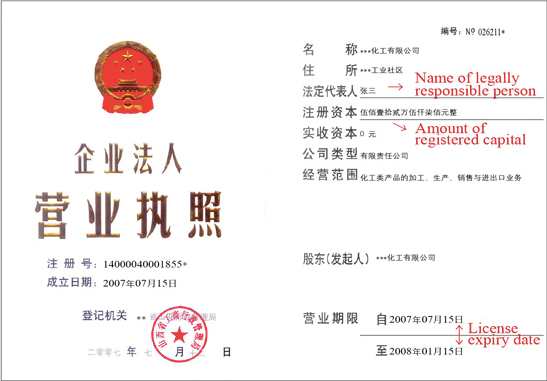

Each Chinese company has in fact a business license issued by SAIC, which contains the following information:

- official company name in Chinese characters;

- registration number;

- registered office;

- company object;

- date of incorporation and expiry;

- legal representative;

- registered and paid-up capital.

It is a Chinese language document, similar to the following:

Verifying the information, with the help of a competent lawyer, will make it possible to ascertain whether or not the company exists, the reliability of the company and whether the self-styled representative can actually act on behalf of the company.

Ask for commercial references

Regardless of whether the Chinese company is interested in importing Italian wine, French fashion or design or other foreign products, an easy check to do is to ask a list international companies with which the Chinese party has previously worked, to validate the information received.

In most cases, the Chinese side will oppose giving references for reasons of privacy, which confirms the suspicion that in reality such phantom success stories do not exist and this is an attempt at fraud.

Manage payments carefully

Having positively marked the first points, it is still advisable to proceed with great caution, especially in the case of a new customer or supplier.

In the case of the sale of products to a Chinese buyer, it is advisable to ask for an advance payment and for the balance of the price when the goods are ready, or the opening of a letter of credit.

In case the Chinese party is the supplier, it is recommended to provide for an on-site inspection of the goods, with a third party to certify the quality of the products and the compliance with the contractual specifications.

Verify requests to change payment methods

If a business relationship is already in progress and you are asked to change the method of payment of the price, you should carefully verify the identity and email account of the applicant and for security it is good to ask for confirmation of the instruction also through other channels of communication (writing to another person in the company, by phone or sending a message via wechat).

How we can help you

Legalmondo offers the possibility to work with a specialized lawyer to examine your need or assist you in the drafting of a contract or contract negotiations with China.

Photo by Andy Beales on Unsplash.

Summary – When can the Coronavirus emergency be invoked as a Force Majeure event to avoid contractual liability and compensation for damages? What are the effects on the international supply chain when a Chinese company fails to fulfill its obligations to supply or purchase raw materials, components, or products? What behaviors should foreign entrepreneurs adopt to limit the risks deriving from the interruption of supplies or purchases in the supply chain?

Topics covered

- The impact of Coronavirus (Covid-19) on the international Supply chain

- What is Force Majeure?

- The Force Majeure Contract Clause

- What is Hardship?

- Is the Coronavirus a Force Majeure or Hardship event?

- What is the event reported by the Supplier?

- Did the Supplier provide evidence of Force Majeure?

- Does the contract establish a Force Majeure or Hardship clause?

- What does the law applicable to the Contract establish?

- How to limit supply chain risks?

The impact of Coronavirus (Covid-19) on the international Supply chain

Coronavirus/Covid 19 has created terrible health and social emergencies in China, which have made exceptional measures of public order necessary for the containment of the virus, like quarantines, travel bans, the suspension of public and private events, and the closure of industrial plants, offices and commercial activities for a certain period of time.

Once the reopening of the plants was authorized, the return to normality was strongly slowed because many workers, who had traveled to other regions in China for the Lunar New Year holiday, did not return to their workplaces.

The current data on the reopening of the factories and the number of staff present are not unambiguous, and it is legitimate to doubt their reliability; therefore, it is not possible to predict when the emergency can be defined as having ended, or if and how Chinese companies will be able to fill the delays and production gaps that have been created.

Certainly, it is very probable that, in the coming months, foreign entrepreneurs will see their Chinese counterparts pleading the impossibility of fulfilling their contracts, with Coronavirus as the reason.

To understand the size of the problem, just consider that in the month of February 2020 alone, the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (the Chinese Chamber of Commerce that is tasked with promoting international commerce) at the request of Chinese companies, has already issued 3,325 certificates attesting to the impossibility of fulfilling contractual obligations due to the Coronavirus epidemic, for a total value of more than 270 billion yuan (US $38.4 bn), according to the official Xinhua News Agency.

What risks does this situation pose for foreign entrepreneurs, and what consequences can it have beyond Chinese borders?

There are many risks, and the potential damages are enormous: China is the world’s factory, and it currently generates roughly 15% of the world’s GDP. Therefore, it is unlikely that a production chain in any industrial sector does not involve one or more Chinese companies as suppliers of raw materials, semi-finished materials, or components (in the case of Italy, the sectors most integrated with supply chains in China are the automotive, chemical, pharmaceutical, textile, electronic, and machinery sectors).

Failure to fulfill on the part of the Chinese may, therefore, result in a cascade of non-fulfillments of foreign entrepreneurs towards their end clients or towards the next link in the supply chain.

The fact that the virus is spreading rapidly (at the moment of publication of this article the situation is already critical in some regions in Italy (and in South Korea and Iran), and cases are beginning to be flagged in the USA) furthermore, makes it possible that production stops and quarantine situations similar to those described could also be adopted in regions and industrial sectors of other countries.

To simplify this picture, let us consider the case of a Chinese supplier (Party A) that supplies a component or performs a service for a foreign company (Party B), which in turn assembles (in China or abroad) the components into a semi-finished or final product, that is then resold to third parties (Party C).

If Party A is late or unable to deliver their product or service to Party B, they risk finding themselves exposed to risks of contract failure versus Party C, and so on along the supply/purchase chain.

Let’s examine how to handle the case in which Party A communicates that it has become impossible to fulfill the contract for reasons related to the Coronavirus emergency, such as in the case of an administrative measure to close the plant, the lack of staff in the factory on reopening, the impossibility of obtaining certain raw materials or components, the blocking of certain logistics services, etc.

In international trade, this situation, i.e. exemption from liability for non-fulfillment of contractual performance, which has become impossible due to events that have occurred outside the sphere of control of the Party, is generally defined as “Force Majeure”.

To understand when it is legitimate for a supplier to invoke the impossibility to fulfill a contract due to the Coronavirus and when instead these actions are unfounded or specious, we must ask ourselves when can Party A invoke Force Majeure and what can Party B do to limit damages and avoid being considered in-breach towards Party C.

What is Force Majeure?

At an international level, a unified concept of Force Majeure doesn’t exist because every different country has established their own specific regulations.

A useful reference is given by the 1980 Vienna Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG), ratified by 93 countries (among which are Italy, China, the USA, Germany, France, Spain, Australia, Japan, and Mexico) and automatically applicable to sales between companies with seat in contracting states.

Art. 79 of CISG, titled, “Impediment Excusing Party from Damages”, provides that, “A party is not liable for a failure to perform any of his obligations if he proves that the failure was due to an impediment beyond his control and that he could not reasonably be expected to have taken the impediment into account at the time of the conclusion of the contract or to have avoided or overcome it or its consequences.”

The characteristics of the cause of exemption from liability for non-fulfillment are, therefore, its unpredictability, the fact that it is beyond the control of the Party, and the impossibility of taking reasonable steps to avoid or overcome it.

In order to establish, in concrete terms, if the conditions for a Force Majeure event exist, what its consequences are, and how the parties should conduct themselves, it is first necessary to analyze the content of the Force Majeure clause (if any) included in the contract.

The Force Majeure Contract Clause

The model Force Majeure clause used for reference in international commerce is the one prepared by the International Chamber of Commerce, la ICC Force Majeure Clause 2003, which provides the requirements that the party invoking force majeure has the burden of proving (in substance they are those provided by art. 79 of CISG), and it indicates a series of events in which these requirements are presumed to occur (including situations of war, embargoes, acts of terrorism, piracy, natural disasters, general strikes, measures of the authorities).

The ICC Force Majeure Clause 2003 also indicates how the party who invokes the event should behave:

- Give prompt notice to the other parties of the impediment;

- In the case in which the impediment will be temporary, promptly communicate to the other parties the end;

- In the event that the impossibility of the performance derives from the non-fulfillment of a third party (as in the case of a subcontractor) provide proof that the conditions of the Force Majeure also apply to the third supplier;

- In the event that this shall lead to the loss of interest in the service, promptly communicate the decision to terminate the contract;

- In the event of termination of the contract, return any service received or an amount of equivalent value.

Given that the parties are free to include in the contract the ICC Force Majeure Clause 2003 or another clause of different content, in the face of a notification of a Force Majeure event, it will, therefore, be necessary, first of all, to analyze what the contractual clause envisages in that specific case.

The second step (or the first, if, in the contract, there is no Force Majeure clause) would then be to verify what the law applicable to the contractual agreement provides (which we will deal with later).

It is also possible that the event indicated by the defaulting party does not lead to the impossibility of the fulfillment of the contract, but makes it excessively burdensome: in this case, you cannot apply Force Majeure, but the assumptions of the so-called Hardship clause could be used.

What is Hardship?

Hardship is another clause that often occurs in international contracts: it regulates the cases in which, after the conclusion of the contract, the performance of one of the parties becomes excessively burdensome or complicated due to events that have occurred, independent of the will of the party.

The outcome of a Hardship event is that of a strong imbalance of the contract in favor of one party. Some textbook examples would be: an unpredictable sharp rise in the price of a raw material, the imposition of duties on the import of a certain product, or the oscillation of the currency beyond a certain range agreed between the parties.

Unlike Force Majeure, in the case of Hardship, performance is still feasible, but it has become excessively onerous.

In this case, the model clause is also that of the ICC Hardship Clause 2003, which provides that Hardship exists if the excessive cost is a consequence of an event outside the party’s reasonable sphere of control, which could not be taken into consideration before the conclusion of the agreement, and whose consequences cannot be reasonably managed.

The ICC Hardship clause stabilizes what happens after a party has proven the existence of a Hardship event, namely:

- The obligation of the parties, within a reasonable time period, to negotiate an alternative solution to mitigate the effects of the event and bring the agreement into balance (extension of delivery times, renegotiation of the price, etc.);

- The termination of the contract, in the event that the parties are unable to reach an alternative agreement to mitigate the effects of the Hardship.

Also, when one of the parties invokes a Hardship event, just as we saw before for Force Majeure, it is necessary to verify if the event has been planned in the contract, what the contents of the clause are, and/or what is established by the norms applicable to the contract.

Is the Coronavirus a Force Majeure or Hardship event?

Let’s return to the case we examined at the beginning of the article, and try to see how to manage a case where a supplier internal to an international supply chain defaults when the Coronavirus emergency is invoked as a cause of exemption from liability.

Let’s start by adding that there is no one response valid in all cases, as it is necessary to examine the facts, the contractual agreements between the parties, and the law applicable to the contract. What we can do is indicate the method that can be used in these cases, that is responding to the following questions:

- The factual situation: what is the event reported by the Supplier?

- Has the party invoking Force Majeure proven that the requirements exist?

- What does the Contract (and/or the General Conditions of Contract) provide for?

- What does the law applicable to the Contract establish?

- What are the consequences on the obligations of the Parties?

What is the event reported by the Supplier?

As seen, the situation of force majeure exists if, after the conclusion of the contract, the performance becomes impossible due to unforeseeable events beyond the control of the obligated party, the consequences of which cannot be overcome with a reasonable effort.

The first check to be complete is whether the event for which the party invokes the Force Majeure was outside the control of the Party and whether it makes performance of the contract impossible (and not just more complex or expensive) without the Party being able to remedy it.

Let’s look at an example: in the contract, it is expected that Party A must deliver a product to Party B or carry out a service within a certain mandatory deadline (i.e. a non-extendable, non-waivable), after which Party B would no longer be interested in receiving the performance (think, for example, of the delivery of some materials necessary for the construction of an infrastructure for the Olympics).

If delivery is not possible because Party A’s factory was closed due to administrative measures, or because their personnel cannot travel to Party B to complete the installation service, it could be included in the Force Majeure case list.

If instead the service of Party A remains possible (for example with the shipping of products from a different factory in another Chinese region or in another country), and can be completed even if it would be done under more expensive conditions, Force Majeure could not be invoked, and it should be verified whether the event creates the prerequisites for Hardship, with the relative consequences.

Did the Supplier provide evidence of Force Majeure?

The next step is to determine if the Supplier/Party A has provided proof of the events that are prerequisites of Force Majeure. Namely, not being able to have avoided the situation, nor having a reasonable possibility of remedying it.

To that end, the mere production of a CCPIT certificate attesting the impossibility of fulfilling contractual obligations, for the reasons explained above, cannot be considered sufficient to prove the effective existence, in the specific case, of a Force Majeure situation.

The verification of the facts put forward and the related evidence is particularly important because, in the event that a cause for exemption by Party A is believed to exist, this evidence can then be used by Party B to document, in turn, the impossibility of fulfilling their obligations towards Party C, and so on down the supply chain.

Does the contract establish a Force Majeure or Hardship clause?

The next step is that of seeing if the contract between the parties, or the general terms and conditions of sale or purchase (if they exist and are applicable), establish a Force Majeure and/or Hardship clause.

If yes, it is necessary to verify if the event reported by the Party invoking Force Majeure falls within those provided for in the contractual clause.

For example, if the reported event was the closure of the factory by order of the authorities and the contractual clause was the ICC Force Majeure Clause 2003, it could be argued that the event falls within those indicated in point 3 [d] or “act of authority” … compliance with any law or governmental order, rule, regulation or direction, curfew restriction” or in point 3 [e] “epidemic” or 3 [g] “general labor disturbance”.

It should then be examined what consequences are provided for in the Clause: generally, responsibility for timely notification of the event is expected, that the party is exempt from performing the service for the duration of the Force Majeure event, and finally, a maximum term of suspension of the obligation, after which, the parties can communicate the termination of the contract.

If the event does not fall among those provided for in the Force Majeure clause, or if there is no such clause in the contract, it should be verified whether a Hardship clause exists and whether the event can be attributed to that prevision.

Finally, it is still necessary to verify what is established by the law applicable to the contract.

What does the law applicable to the Contract establish?

The last step is to verify what the laws applicable to the contract provide, both in the case when the event falls under a Force Majeure or Hardship clause, and when this clause is not present or does not include the event.

The requirements and consequences of Force Majeure or Hardship can be regulated very differently according to the applicable laws.

If Party A and Party B were both based in China, the law of the People’s Republic of China would apply to the sales contract, and the possibility of successfully invoking Force Majeure would have to be assessed by applying these rules.

If instead, Party B were based in Italy, in most cases, the 1980 Vienna Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods would apply to the sales contract (and as previously seen, art.79 “Impediment Excusing Party from Damages”). As far as what is not covered by CISG, the law indicated by the parties in the contract (or in the absence identified by the mechanisms of private international law) would apply.

Similar reasoning should be applied when determining which law are applicable to the contract between Party B and Party C, and what this law provides for, and so on down the international supply chain.

No problems are posed when the various relationships are regulated by the same legislation (for example, the CISG), but as is likely the case, if the applicable laws were different, the situation becomes much more complicated. This is because the same event could be considered a cause for exemption from contractual liability for Party A to Party B, but not in the next step of the supply chain, from Party B to Party C, and so on.

How to limit supply chain risks?

The best way to limit the risk of claims for damages from other companies in the supply chain is to request timely confirmation from your Supplier of their willingness to perform the contractual services according to the established terms, and then to share that information with the other companies that are part of the supply chain.

In the case of non-fulfillment motivated by the Coronavirus emergency, it is essential to verify whether the reported event falls among those that may be a cause of contractual exemption from liability and to require the supplier to provide the relevant evidence. The proof, if it confirms the impossibility of the supplier’s performance, can be used by the buyer, in turn, to invoke Force Majeure towards other companies in the Supply Chain.

If there are Force Majeure/Hardship clauses in the contracts, it would be necessary to examine what they establish in terms of notice of the impossibility to perform, term of suspension of the obligation, consequences of termination of the contract, as well as what the laws applicable to the contracts provide.

Finally, it is important to remember that most laws establish a responsibility of the non-defaulting party to mitigate damages deriving from the possible non-fulfillment of the other party. This means that if it is probable, or just possible, that the Chinese Supplier will default on a delivery, the purchasing party would then have to do everything possible to remedy it, and in any case, fulfill their obligations towards the other companies that form part of the supply chain; for example by obtaining the product from other suppliers even at greater expense.

————————————-

Legalmondo has created a Help Desk on the Coronavirus Emergency

Click below and let us know your need

————————————-

Quick Summary – Why is it important to register one’s trademark in China? To acquire the exclusive right to use the trademark in the Chinese market and prevent any third party from doing so, thus blocking access to the market for the foreign company’s products or services. This post describes how to register a trademark in China and why it is important to register it even if the foreign company is not yet present in the local market. We will also address the matter of a trademark in Chinese characters, illustrating in which cases it might be useful to register a transliteration of the international trademark.

Foreign Companies are often unpleasantly surprised by the fact that their trademark has already been registered in China by a local party: in such cases it is very difficult to have the trademark registration revoked and they may find themselves unable to sell their own products or services in China.

Why you should register your trademark in China

The Chinese trademark registration system is governed by the first-to-file principle, which provides for a presumption that the subject who first registers a trademark shall be considered its lawful owner (unlike other countries such as the USA and Canada, which follow the first-to-use principle, where the key is represented by the first use of the trademark).

The first-to-file principle has also been implemented by others (Italy and the European Union, for example), but its application in China is among the most stringent, as it does not entitle a previous user to continue to use a trademark once it has been registered by another subject.

Therefore, when a third party registers your distinctive mark in China first, you will no longer have the option to keep using it on Chinese territory, unless you manage to have the registration of the trademark cancelled.

In China, however, it is quite complex to get a trademark revoked, which is possible solely under one of the following circumstances.

The first one consists in proving that the third party’s registration of the trademark has been achieved by fraudulent or unlawful means. In order to do so, it is necessary to prove that the trademark registrant was aware of its previous use and has acted with the intention of obtaining an unlawful advantage, hence the registration was achieved in bad faith.

The second one involves proof that the registered trade mark is identical, similar or a translation of a well-known distinctive mark already used by another subject in China and that the new registration is likely to mislead the public. As an example, a Chinese subject registers the translation of an internationally known trademark, which had been registered in China in Latin characters only.

This second path is tricky too, because it requires the trademark to have a status of international notoriety, which under Chinese jurisprudence recurs when a large number of local consumers know and recognize the trademark.

A third case occurs when the Trademark has been registered by a third party in China, but hasn’t been used for three consecutive years: if so, the law provides that anyone who is interested may apply for the cancellation of the trademark, specifying whether he wants to cancel the entire registration or only in relation to certain classes / subclasses.

Even this third way is rather complex, especially with reference to the cancellation of the entire registration: for the Chinese trademark owner, in fact, it is sufficient to prove even a slightest use (for example on a website or a wechat account) to have the registration saved.

For these reasons, it is crucial to file the application for registration in China before a third party does so, in order to prevent similar or even identical marks/logoes from being registered – which are often in bad faith.

The process for trademark registration in China

Two alternative ways of registering a trademark in China are feasible:

- either you can file the application for registration directly with the Chinese Trademark Office (CTMO); or

- choose an international registration by submitting the relevant application to the WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization), with a subsequent designation request for an extension to China.

In my opinion, it is advisable to pursue a trademark registration directly with the CTMO (Chinese Trademark Office). International extension by the WIPO are based on a standardized registration process, which does not take into account all the complexities characterizing the Chinese system, according to which:

- The first step shall be to conduct a check in order to ascertain whether similar and/or identical trademarks have already been registered, along with an evaluation of the legal requirements for the trademark’s validity.

- Second, the applicant must select the class(es) and sub-class(es) under which the relevant trade mark is to be registered.

This process is somewhat complex, since the CTMO, besides the designation of the class of registration within the 45 classes covered by the International Classification (“Nice Classification of Goods and Services”), requires as well an indication of the subclasses. There are several Chinese subclasses for each class, and they do not match with the International Classification.

As a consequence, by submitting your application through the WIPO, your trade mark would be registered in the correct class, but the designation of the subclasses will be made ex officio by the CTMO, without the applicant being involved. This may lead to the registration of the trademark in subclasses that do not correspond to the ones desired, entailing the risk, on the one hand, of an increase in registration costs (if the subclasses are inflated); on the other hand, it may result in a limited protection on the market (if the trademark is not registered under a certain subclass).

Another practical aspect which would make direct registration in China preferable lies in the immediate gain of a certificate in Chinese; this enables you to move quickly and effectively (with no need for additional certificates or translations) in case you need to use your trademark in China (e.g. for legal or administrative actions against counterfeit or if you need to register a trademark license agreement).

The registration procedure in China itself involves several steps and is generally concluded within a time frame of about 15/18 months: priority, however, is acquired from the date of filing, thus ensuring protection against any application for registration by a third party at a later date.

Registration lasts 10 years and is renewable.

Trade mark registration in Chinese characters

Is it really necessary to register the Trademark also in Chinese characters?

For most companies, yes. Very few people speak English in China, so international terms are often difficult to pronounce and are often replaced by a Chinese word that sounds like the foreign word, making it easier for Chinese consumers or customers to read and memorize it.

Transliteration of the international trademark into Chinese characters can be achieved in several ways.

First of all, it is possible to register a term that presents assonance with the original, as in the case of Ferrari / 法拉利 (fǎlālì, phonetic transliteration without particular meaning) or Google / 谷歌 (Gǔgē, also a phonetic transliteration).

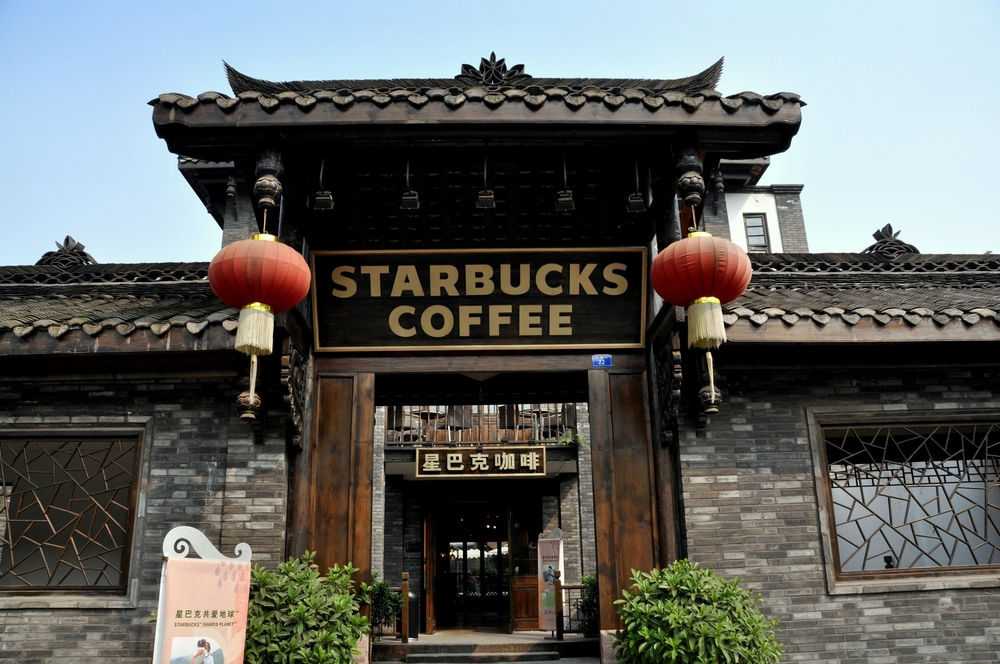

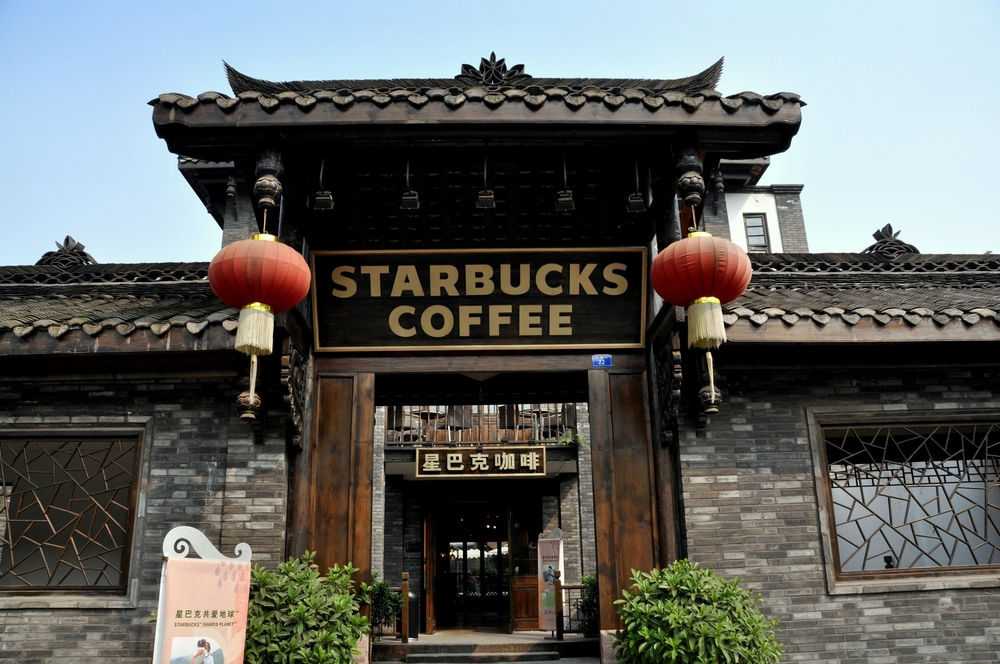

As an alternative a term equivalent to the meaning of the foreign word can be chosen, such as in the case of Apple / 苹果(Píngguǒ, which means apple) and partly in the case of Starbucks / 星巴克 (xīngbākè: the first character means “star”, while bākè is a phonetic transliteration).

The third option would be to identify a term that carries both a positive meaning related to the product and at the same time recalls the sound of the foreign brand, as in the case of Coca Cola / Kěkǒukělè (i.e. taste and be happy).

(Below the trademark Ikea / 宜家 =yíjiā, namely harmonious home)

As for the trademark in Latin characters, there is a strong risk that third parties may register the Chinese version of the trademark before the lawful owner.

This is compounded by the fact that the third party who registers a similar or confusing trademark in Chinese characters typically does so in order to exploit unfairly the fame and the commercial goodwill of the foreign trademark by addressing the same customers and sales channels.

Recently, the Jordan (owned by the group of companies belonging to the basketball champion) and New Balance, for example, struggled for some time to have their corresponding Chinese trademarks cancelled, which had been registered in bad faith by their competitors.

Registration rules for a trademark in Chinese characters are the same as those mentioned above for a trademark in Latin characters.

Since there may be risks related to possible third party registrations, it is advisable to extend the assessment of trademark registration not only to the Chinese characters that have been identified for the Mandarin version that you decided to use, but also to a number of phonetically similar trademarks, which should prevent any third party from registering trademarks that may be confused with the company’s trademark.

Furthermore, it is also advisable to register a trademark in Chinese characters, even if the business strategy does not involve the use of a trademark in Chinese characters. In such cases, the registration of terms that correspond to the phonetic transliteration of the international trademark serves a protective purpose, namely to prevent registration (and use) by third parties.

The latter has been done, for example, by important brands such as Armani and Prada, which have registered trademarks in Chinese characters (respectively 阿玛尼 / āmǎní and 普拉達 = pǔlādá) although they do not currently use them in their communication.

Regarding the different transliteration options, it is advisable to be supported by local consultants in the evaluation of the characters, to avoid choosing terms with unhappy, unsuitable or even inauspicious meanings (as in the case of one of my clients who registered an Italian trademark many years ago using the final character 死, which sounds like the word “dead” in Chinese).

One of the commonly discussed advantages of international commercial arbitration over litigation in the cross-border context is the enforcement issue. For the purpose of swifter enforcement of foreign arbitral awards, the vast majority of countries signed the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards.

On contrary, there is no relevant international treaty of such scale for the enforcement of foreign court judgements. Normally, the special legal basis, such as agreement on judicial cooperation between two or more countries, needs to be relied upon in order to get a court judgment recognized and enforced in another country. There are quite many countries that do not have such an agreement with China. This includes, among others, US, Germany or the Netherlands.

Interestingly, however, recently the Chinese court in Wuhan enforced the US court judgement rendered by the Los Angeles Superior Court of California in the Liu Li v Tao Li and Tong Wu case. It did so despite the fact that there is no agreement between China and US providing for mutual recognition and enforcement of such judgements. The court in Wuhan found, however, that the reciprocity in recognizing and enforcing the court judgments between China and US was established because of an earlier decision of the US District Court of the Central District of California recognizing and enforcing the Chinese judgement rendered by the Higher People’s Court of Hubei in the Hubei Gezhouba Sanlian Industrial Co., Ltd et. al. v Robinson Helicopter Co., Inc. case.

Interestingly, similar course of action was taken earlier in 2016 when the Chinese Nanjing Intermediate People’s Court enforced the Singaporean judgement relying on the reciprocity principle in the Kolma v SUTEX Group case.

How much does it tell us?

Should we now feel safe when opting for own courts in the dispute resolution clauses in the China-related deals? – despite the fact there are no relevant agreements between China and our country? The recent moves of the Chinese courts are, indeed, interesting developments changing the dispute resolution landscape in a desirable direction and increasing the chances for enforcing the foreign commercial court judgements. Yet, as of today, one should not see them as the universal door-openers for the foreign court judgements in similar situations. Accordingly, rather careful approach is recommended and the other dispute resolution methods securing the safer way of enforcement, like arbitration, should be kept in mind. The further changes remain to be seen.

The author of this post is Monika Prusinowska.

There is a number of dispute resolution mechanisms available for the disputes with the Chinese parties. Depending on bargaining power of the parties and few other circumstances, such as limitations of Chinese law, the dispute can be sometimes resolved outside of China. More frequently, however, the Sino-foreign disputes are resolved in China and this post offers a brief introduction to the methods available there .

As almost anything else in business, an optimal method for resolution of future disputes is worth of anticipating well in advance. Once there is a conflict, it is much more difficult for the parties to agree on the solution equally acceptable to both of them. There is a variety of options to choose from and each of them has its own advantages and disadvantages. Also, there is no “one size fits all” solution and each transaction as well as dispute should be approached individually. Of course, there is always is a default solution, which is going to state court in case the parties have not provided for any alternative mechanism, but this is not always the most optimal way to go.

Litigation

Chinese courts are commonly perceived by foreigners as rather undesirable scenario for dispute resolution. It is so due to the often mentioned problems, such as local protectionism of the Chinese courts or lack of their professionalism. However, in practice, this is not always true and especially the courts in the China’s well-developed regions, particularly in the biggest coastal cities are generally a safe harbor for disputes involving foreigners. The same holds true for the IP courts located in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. One needs to remember, however, that the jurisdiction of particular court depends on a number of factors, such as place of registration of the Chinese counterparty or place of performance of the contract and therefore, the Chinese top courts may not be the ones handling particular dispute in practice.

Arbitration

Arbitration is a common choice for foreign-related disputes in China. It happens so, because of a number of advantages of arbitration over litigation in such a context. To start with, China and the vast majority of the countries in the world are the parties to the New York Convention, which significantly streamlines the enforcement of foreign arbitral awards. There is no comparable treaty of that scale for the enforcement of state court judgements, what can cause practical problems if certain country does not have an agreement on judicial assistance with China and the enforcement of foreign court judgements is sought. Therefore, since the parties want money and not a piece of paper, the use of arbitration in the cross-border context can substantially improve the prospects for effective enforcement of arbitral award. Furthermore, in contrast to litigating in China, in arbitration English language can be used in proceeding and a party can be represented by a foreign counsel. In arbitration, the parties can also select arbitrators resolving their dispute and a foreign arbitrator is not an uncommon scenario in case of the Sino-foreign arbitration proceedings in China. The parties can also select a specific arbitration institution and rules applicable to the proceeding.

The China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC) and the Beijing Arbitration Commission (BAC) are one of the most frequently chosen arbitration institutions in China for the foreign-related disputes. Alternatively, if the circumstances of the case permit – the dispute can be taken outside of China and resolved, for instance, by the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC) or the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC), which are fairly acceptable alternative choices for the Chinese parties.

Other options

One of the other methods popular in China is mediation. Mediation is typically faster, cheaper and increases the chances of preserving good relationship between the parties. However, one needs to remember that in order to mediate, the parties need to be willing to do so, since the role of mediator is to help the parties reach an agreement and not to ultimately decide their dispute. Furthermore, the product of mediation is a contract and so, the breach of mediation agreement typically equals to contractual breach.

One additional important tool frequently used in practice is engaging local lawyers for the purpose of negotiating with the Chinese party as soon as the dispute escalates. The lawyers can help the parties communicate and when the communication is impossible – they can prepare a document describing the claims and informing the Chinese party about the risk of undertaking further legal steps, such as staring court proceeding, what is made mainly for the purpose of brining the other party back to negotiation and finding a solution acceptable to both parties. This often helps save time and money, but it can be problematic if the other party ignores the actions of lawyer. Also, like in case of mediation, the problem lies in the enforcement of any agreement reached by the parties in the course of negotiation.

The main takeaways from this short post are the following:

- Think about the dispute resolution mechanism in advance. There are quite many issues that need to be taken into consideration and there is no “one size fits all” solution. There might be the situations when going to the Chinese court makes perfect sense and there also might be the situations when it makes no sense at all. What is the best option for me in particular case? Which court can potentially have jurisdiction over my case? Does the country involved have a judicial assistance agreement with China for the purpose of enforcement? What should be the language of proceeding? Which arbitration institution to choose?

- Think about hiring professionals right from the very beginning, preferably at the stage of negotiating and drafting agreements. Choosing an optimal solution for resolution of future disputes can help save a lot of time, money and energy. In case of dispute occurring already – act promptly. If the dispute escalates, think about what you can do to best preserve your rights. Should you apply for interim measures? Do you need to first negotiate before you can go for arbitration in case of multi-tier clauses? Which documents are needed to start the proceeding?

The author of this post is Monika Prusinowska.

目标公司董事会须公布讨论内容吗?

目标公司董事会无披露任何谈判及讨论的内容的义务,则须保密直至保密义务结束或要约收购完成。若泄密或目标公司股票价格有异常变动,则须发布公告。

目标公司可如何抵制管控的变化?

原则上,目标公司可以尝试实施若干防御措施以抵制恶意收购(例如执行“皇冠之珠”、回购、库存股票转让、免费发行认股权证、寻找“白衣骑士”等)。然而,被动规则通常适用于有价证券涉及要约收购的意大利上市公司,因此自公布之日起至收购结束或到期期间,目标公司通常应该避免采取任何可能妨碍要约收购成功的行动,但目标公司董事会批准此类防御行动的除外。

目标公司必须向监管委员会和其股票上市所在国的收购监管机构报告其放弃被动规则的所有决议。

对于外国收购者,若强制放弃所有可能干扰收购完成的行动的被动规则,或目标公司章程可能包含的突破性规定,不适用于由不受该等规定或收购方证券上市国家的同等规定约束的实体启动的要约收购或交换股权收购。

是一场公平的战斗吗?

最终,这主要取决于目标公司股东做出的决定。目标公司的董事会可能会因认为收购不符合公司最大利益而抵制收购。但董事会采取任何防御措施前,都须获得大多数股东的同意。

被允许的交易条件是哪些?有什么限制?

作为一般规则,要约收购的成功不可受限于收购方单方面提出的条件。

但是,自愿的现金或股权互换要约收购可以受限于某些前述条件。其中可能被允许的最常见的条件有:

- 进行投标最低持股数量的要求;

- 获得相关机构所有必要的核准;

- 目标公司缺乏某些可能对收购产生负面影响,或决定中止收购的防御行为。

收购方的上述先决条件必须在以下文件中标明:(i)需向监管委员会备案的披露收购方收购意向的通讯记录;(ii)招募备忘录;(iii)收购的相关表格文件。

在强制收购的情况下,根据定义,强制收购不得受制于任何条件。

在收购过程中收购方可如何控制目标公司?

收购方在收购过程中仅可行使较少的控制权并对目标公司施加有限的影响;另一方面,目标公司董事在采取所有阻挠收购的行动前,须获得股东批准。

收购方何时开始管控公司?

一旦要约收购完成并支付收购价款后,目标公司的有价证券将被转移给收购方。届时,收购方必须召开目标公司股东大会以任命新一届董事会。为使收购方获得目标公司的控制权,在收购方无论何时通过要约收购获得目标公司至少75%的拥有普通股东会议投票权的证券后,根据《统一财政法案》的规定,在第一次为罢免或任命董事,或修改目标公司章程而召开的股东大会上,不可强制执行以下内容:

- 对目标公司投票权进行任何法定或合同限制;或

- 目标公司章程规定的关于董事任免的任何特别权利,以及确定额外“增加”的投票权的章程规定。

收购方如何获得100%控制权?

在强制排除程序中,若收购方已通过要约收购认购目标公司不少于95%有投票权的有价证券,则收购方可认购目标公司所有有投票权的有价证券。在该情形下,若强制排除少数股东的意图已在收购文件中进行声明,在收购完成后的90日内,收购方有权从其他股东处认购剩余的有价证券。

写信给 China – Changes to Company Law

China – Internet Frauds and online Scams

25 8 月 2020

-

中国

- 分销协议

Summary:

The heavily amended PRC Company Law will take effect on July 1, 2024. Please find below a summary of some of the important novelties embodied by this amended Company Law, which may have a significant impact on the rights and duties of the shareholders and management of a limited liability company (“LLC”).

The businesses active in the PRC may be interested in carefully reviewing their corporate documents (including the Articles of Association) in light of the amended Company Law and deciding necessary adaptive measures for compliance/optimization purposes during the transition period leading to the effective date of the said amended Company law.

Capital contribution.

The amended Company Law provides that the subscribed capital of an LLC shall be paid up as per its Articles of Association within a time period up to 5 years from its incorporation (NB: The previous law does not set a time limit for the capital contribution.). This requirement will retroactively apply to the companies incorporated prior to July 1st, 2024.

Despite the foregoing, a creditor or the company shall be entitled to request the shareholder(s) concerned to accelerate its/their capital contribution ahead of the due date for capital contribution should the company be unable to settle due debt(s) with its own assets.

The equity and credit may be used for the capital contribution.

Duties of directors/senior managers

The directors shall bear the obligation to form the “liquidation team,” which shall proceed with the liquidation within 15 days of the occurrence of a number of statutory circumstances substantiated in Article 229 of the Company Law. The directors shall be held liable for losses incurred by the company or creditor(s) arising from their failure to fulfill the above liquidation obligation on time.

The director(s)/senior manager(s) shall be held liable (along with the company itself) for compensating others should they cause any damages to the latter due to their intentional acts or gross negligence in the course of performing their duties.

The board of directors of an LLC shall regularly check the status of capital contributions by the shareholders. It shall cause the company to issue written reminders to the shareholder(s) failing to make capital contributions on time. Should the shareholder fail to honor its subscribed capital contribution despite the reminder, subject to a specific board resolution and a written notification with immediate effect, the company may declare that the shareholder is disqualified from making the capital contribution.

Corporate governance

An LLC may set up an “audit commission” composed of directors to exercise the function of supervisor or supervisors’ committee as per its Articles of Association. In such cases, the company may no longer need to set up separate supervisors’ committees or appoint supervisors.

However, the board of directors of an LLC having more than 300 employees shall have employees’ representative(s) elected through the democratic process unless the same LLC has a Supervisors’ Committee in place and such Committee already has the employees’ representative(s).

Summary – The Covid-19 emergency has accelerated the transition to e-commerce, both in B2C relationships and in many B2B sectors. Many companies have found themselves operating on the Internet for the first time, shifting their business and customer relationships to the digital world. Unfortunately, it is often the case that attempts at fraud are concealed behind expressions of interest from potential customers. This is particularly the case with new business contacts from China, via email or via the company’s website or social network profiles. Let’s see what the recurrent scams are, small and large, which happen frequently, especially in the world of wine, food, design, and fashion.

What I’m talking about in this post:

- The request for products via the internet from a Chinese buyer

- The legalization of the contract in China, the signature by the Chinese notary public and other expenses

- The modification of payment terms (Man in the mail)

- The false registration of the brand or domain web

- Design and fashion: the phantom e-commerce platform

- The bitcoin and cryptocurrency trader

- How to verify the data of a Chinese company

- How we can help you

Unmissable deal or attempted fraud?

Fortunately, the bad guys in China (and not only: this kind of scams are often perpetrated also by criminals from other countries) are not very creative and the types of scams are well known and recurrent: let’s see the main ones.

The invitation to sign the contract in China

The most frequent case is that of a Chinese company that, after having found information about the foreign products through the website of the company, communicates by email the willingness to purchase large quantities of the products.

This is usually followed by an initial exchange of correspondence via email between the parties, at the outcome of which the Chinese company communicates the decision to purchase the products and asks to finalize the agreement very quickly, inviting the foreign company to go to China to conclude the negotiation and not let the deal fade away.

Many believe it and cannot resist the temptation to jump on the first plane: once landed in China the situation seems even more attractive, since the potential buyer proves to be a very surrendering negotiator, willing to accept all the conditions proposed by the foreign party and hasty to conclude the contract.

This is not a good sign, however: it must sound like a warning.

It is well known that the Chinese are skillful and very patient negotiators, and commercial negotiations are usually long and nerve-wracking: a negotiation that is too easy and fast, especially if it is the first meeting between the parties, is very suspicious.

That you are faced with an attempted scam is then certified by the request for some payments in China, allegedly necessary for the deal.

There are several variants of this first scheme.

The most common are the request to pay a fee for the registration of the contract with a Chinese notary public; a fee for administrative or customs duties; a cash payment for costs of licenses or import permits for the goods, the offer of lunches or dinners to potential business partners (at inflated prices), the stay in a hotel booked by the Chinese side, followed by the surprise of an exorbitant bill.

Back home, unfortunately, very often the signed contract will remain a useless piece of paper, the phantom client will become unavailable and the Chinese company never return the emails or calls of the foreign client. You will then have the certainty that the entire operation was designed with the sole purpose of extorting the unwary foreigner a few thousand euros.

The same scheme (i.e. the commercial order followed by a series of payment requests) can also be carried out online, for reasons similar to those indicated: the clues of the scam are always the contact by a stranger for a very high value order, a very quick negotiation with a request to conclude the deal in a short time and the need to make some payment in advance before concluding the contract.

Payment to a different bank account

Another very frequent scam is the bank account scam which is different from the one usually used.

Here the parts are usually reversed. The Chinese company is the seller of the products, from which the foreign entrepreneur intends to buy or has already bought a number of products.

One day the seller or the agent of reference informs the buyer that the bank account normally used has been blocked (the most frequent excuses are that the authorized foreign currency limit has been exceeded, or administrative checks are in progress, or simply the bank used has been changed), with an invitation to pay the price on a different current account, in the name of another person or company.

In other cases, the request is motivated by the fact that the products will be supplied through another company, which holds the export license for the products and is authorized to receive payments on behalf of the seller.

After making the payment, the foreign buyer receives the bitter surprise: the seller declares they never received the payment, that the different bank account does not belong to the company and that the request for payment to another account came from a hacker who intercepted the correspondence between the parties.

Only then, by verifying the email address from which the request for use of the new account was sent, the buyer generally sees some small difference in the email account used for the payment request on the different account (e.g. different domain name, different provider or different username).

The seller will then only be willing to ship the goods on condition that the payment is renewed on the correct bank account, which – obviously – one should not do, to avoid being deceived a second time. Verification of the owner of the false bank account generally does not lead to any response from the bank and it will in fact be impossible to identify the perpetrators of the scam.

The scam of the fake Chinese Trademark Agent

Another classic Chinese scam is the sending of an email informing the foreign company that a Chinese person intends to register a trademark or a web domain identical to that of the foreign company.

The sender is a self-proclaimed Chinese agency in the sector, which communicates its willingness to intervene and avert the danger, blocking the registration, provided that it is done in a very short time and the foreigner pay the service in advance.

In this case too we are faced with a clumsy attempt at fraud: better to trash the email immediately.

By the way: If you haven’t registered your trademark in China, you should do so right now. If you are interested in learning more about it, you can read this post.

Designers and fashion products: the phantom Chinese e- commerce platform

A widespread scam is the one involving designers and companies in the fashion industry: also in this case the contact arrives through the website or the social media account of the company and expresses a great interest in importing and distributing in China products of the Italian designer or brand.

In the cases that I have dealt with in the past, the proposal is accompanied by a substantial trademark license and distribution contract in English, which provides for the exclusive granting of the trademark and the right to sell the products in China in favor of a Chinese online platform, currently under construction, which will make it possible to reach a very large number of customers.

After signing the contract, the pretexts to extort money from the foreign company are similar to those seen previously: invitation to China and request a series of payments on site, or the need to cover a series of costs to be borne by the Chinese side to start business operations in China for the foreign company: trademark registration, customs requirements, obtaining licenses, etc. (needless to say, all fictional: the platform does not exist, nothing will be done and the contact person will vanish soon after she has received the money).

The bitcoin and cryptocurrency scam

Recently a scam of Chinese origin is the proposal to invest in bitcoin, with a very attractive guaranteed minimum return on investmen (usually 20 or 30%).

The alleged trader presents himself in these cases as a representative of an agency based in China, often referring to a purpose-built website and presentations of investment services made in English.

This scheme usually involves also an international bank, which acts as agent or depository of the sums: in reality, the writer is always the criminal organization, from a bogus account which resembles that of the bank or financial intermediary.

Once the sums are paid the broker disappears and it is not possible to trace the funds because the bank account is closed and the company disappears, or because the payments were made through bitcoin.

The clues of the scam are similar to those seen previously: contact from the Internet or via email, very tempting business proposal, hurry to conclude the agreement and to receive a first payment in China.

How to figure out if we’re dealing with an internet scam

In the cases mentioned above, and in other similar cases, once the scam has been perpetrated there is almost no point in trying to remedy it: the costs and legal fees are usually higher than the money lost and in most cases it is impossible to trace the person responsible for the scam.

Here then is some practical advice – in addition to common sense – to avoid falling into traps similar to those described

How to verify the data of a Chinese company

The name of the company in Latin characters and the website in English have no official value, they are just fancy translations: the only way to verify the data of a Chinese company, and to know the people who represent it (or say they do) is to check out the original business license through the online portal of the SAIC (State Administration for Industry and Commerce).

Each Chinese company has in fact a business license issued by SAIC, which contains the following information:

- official company name in Chinese characters;

- registration number;

- registered office;

- company object;

- date of incorporation and expiry;

- legal representative;

- registered and paid-up capital.

It is a Chinese language document, similar to the following:

Verifying the information, with the help of a competent lawyer, will make it possible to ascertain whether or not the company exists, the reliability of the company and whether the self-styled representative can actually act on behalf of the company.

Ask for commercial references

Regardless of whether the Chinese company is interested in importing Italian wine, French fashion or design or other foreign products, an easy check to do is to ask a list international companies with which the Chinese party has previously worked, to validate the information received.

In most cases, the Chinese side will oppose giving references for reasons of privacy, which confirms the suspicion that in reality such phantom success stories do not exist and this is an attempt at fraud.

Manage payments carefully

Having positively marked the first points, it is still advisable to proceed with great caution, especially in the case of a new customer or supplier.

In the case of the sale of products to a Chinese buyer, it is advisable to ask for an advance payment and for the balance of the price when the goods are ready, or the opening of a letter of credit.

In case the Chinese party is the supplier, it is recommended to provide for an on-site inspection of the goods, with a third party to certify the quality of the products and the compliance with the contractual specifications.

Verify requests to change payment methods

If a business relationship is already in progress and you are asked to change the method of payment of the price, you should carefully verify the identity and email account of the applicant and for security it is good to ask for confirmation of the instruction also through other channels of communication (writing to another person in the company, by phone or sending a message via wechat).

How we can help you

Legalmondo offers the possibility to work with a specialized lawyer to examine your need or assist you in the drafting of a contract or contract negotiations with China.

Photo by Andy Beales on Unsplash.

Summary – When can the Coronavirus emergency be invoked as a Force Majeure event to avoid contractual liability and compensation for damages? What are the effects on the international supply chain when a Chinese company fails to fulfill its obligations to supply or purchase raw materials, components, or products? What behaviors should foreign entrepreneurs adopt to limit the risks deriving from the interruption of supplies or purchases in the supply chain?

Topics covered

- The impact of Coronavirus (Covid-19) on the international Supply chain

- What is Force Majeure?

- The Force Majeure Contract Clause

- What is Hardship?

- Is the Coronavirus a Force Majeure or Hardship event?

- What is the event reported by the Supplier?

- Did the Supplier provide evidence of Force Majeure?

- Does the contract establish a Force Majeure or Hardship clause?

- What does the law applicable to the Contract establish?

- How to limit supply chain risks?

The impact of Coronavirus (Covid-19) on the international Supply chain

Coronavirus/Covid 19 has created terrible health and social emergencies in China, which have made exceptional measures of public order necessary for the containment of the virus, like quarantines, travel bans, the suspension of public and private events, and the closure of industrial plants, offices and commercial activities for a certain period of time.

Once the reopening of the plants was authorized, the return to normality was strongly slowed because many workers, who had traveled to other regions in China for the Lunar New Year holiday, did not return to their workplaces.

The current data on the reopening of the factories and the number of staff present are not unambiguous, and it is legitimate to doubt their reliability; therefore, it is not possible to predict when the emergency can be defined as having ended, or if and how Chinese companies will be able to fill the delays and production gaps that have been created.

Certainly, it is very probable that, in the coming months, foreign entrepreneurs will see their Chinese counterparts pleading the impossibility of fulfilling their contracts, with Coronavirus as the reason.

To understand the size of the problem, just consider that in the month of February 2020 alone, the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (the Chinese Chamber of Commerce that is tasked with promoting international commerce) at the request of Chinese companies, has already issued 3,325 certificates attesting to the impossibility of fulfilling contractual obligations due to the Coronavirus epidemic, for a total value of more than 270 billion yuan (US $38.4 bn), according to the official Xinhua News Agency.

What risks does this situation pose for foreign entrepreneurs, and what consequences can it have beyond Chinese borders?

There are many risks, and the potential damages are enormous: China is the world’s factory, and it currently generates roughly 15% of the world’s GDP. Therefore, it is unlikely that a production chain in any industrial sector does not involve one or more Chinese companies as suppliers of raw materials, semi-finished materials, or components (in the case of Italy, the sectors most integrated with supply chains in China are the automotive, chemical, pharmaceutical, textile, electronic, and machinery sectors).

Failure to fulfill on the part of the Chinese may, therefore, result in a cascade of non-fulfillments of foreign entrepreneurs towards their end clients or towards the next link in the supply chain.

The fact that the virus is spreading rapidly (at the moment of publication of this article the situation is already critical in some regions in Italy (and in South Korea and Iran), and cases are beginning to be flagged in the USA) furthermore, makes it possible that production stops and quarantine situations similar to those described could also be adopted in regions and industrial sectors of other countries.

To simplify this picture, let us consider the case of a Chinese supplier (Party A) that supplies a component or performs a service for a foreign company (Party B), which in turn assembles (in China or abroad) the components into a semi-finished or final product, that is then resold to third parties (Party C).

If Party A is late or unable to deliver their product or service to Party B, they risk finding themselves exposed to risks of contract failure versus Party C, and so on along the supply/purchase chain.

Let’s examine how to handle the case in which Party A communicates that it has become impossible to fulfill the contract for reasons related to the Coronavirus emergency, such as in the case of an administrative measure to close the plant, the lack of staff in the factory on reopening, the impossibility of obtaining certain raw materials or components, the blocking of certain logistics services, etc.

In international trade, this situation, i.e. exemption from liability for non-fulfillment of contractual performance, which has become impossible due to events that have occurred outside the sphere of control of the Party, is generally defined as “Force Majeure”.

To understand when it is legitimate for a supplier to invoke the impossibility to fulfill a contract due to the Coronavirus and when instead these actions are unfounded or specious, we must ask ourselves when can Party A invoke Force Majeure and what can Party B do to limit damages and avoid being considered in-breach towards Party C.

What is Force Majeure?

At an international level, a unified concept of Force Majeure doesn’t exist because every different country has established their own specific regulations.

A useful reference is given by the 1980 Vienna Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG), ratified by 93 countries (among which are Italy, China, the USA, Germany, France, Spain, Australia, Japan, and Mexico) and automatically applicable to sales between companies with seat in contracting states.