-

意大利

How to manage the impact of tariffs on the international supply chain

9 2 月 2025

- 分销协议

Duties are not paid by foreign governments (as Donald Trump repeatedly said on the electoral campaign) but by the importing companies of the country that issued the tax on the value of the imported product, i.e., in the case of the Trump administration’s recent round of tariffs, U.S. companies. Similarly, Canadian, Mexican, Chinese, and – probably – European companies will pay the import duties on U.S.-origin products levied by their respective countries as a trade retaliation measure against U.S. tariffs.

In this context, several scenarios open up, all of them problematic

- U.S. companies will pay the import taxes

- foreign companies exporting taxed products to the U.S., will see export volumes fall as a result of the price increase

- foreign companies that import products from the U.S., in turn, will pay tariffs imposed by their countries in retaliation to U.S. duties

- intermediate or end customers in markets affected by the tariffs will pay a higher price for imported products

Does the imposition of the duty constitute force majeure?

A frequent first objection of the party affected by the duty (it may be the buyer-importer or the one who resells the product after paying the duty), in such cases, is to invoke force majeure to evade the performance of the contract, which, as a result of the duty has become too onerous.

The application of the duty, however, does not fall under force majeure since we are not faced with an unforeseeable event, resulting in the objective impossibility of fulfilling the contract. The buyer/importer, in fact, can always fulfill the contract, with only the issue of price increase.

Does the imposition of the duty constitute a cause of hardship?

If a situation of excessive onerousness arises after the conclusion of the contract (hardship), the affected party has the right to demand a revision of the price or to terminate the contract.

Is this the case for tariffs? A case-by-case assessment is needed, leading to a finding of recurrence of hardship if an extraordinary and unforeseeable situation exists (in the case of the U.S. duties, which have been announced for months, it isn’t easy to support this) and the price, as a result of the application of the tariff, is manifestly excessive.

These are exceptional situations, rarely applied, and should be investigated further based on the law applicable to the contract. Generally, price fluctuations in international markets are part of business risk and do not constitute sufficient grounds for renegotiating concluded agreements, which remain binding unless the parties have included a hardship clause (discussed below).

Does the application of the tariff entail a right to renegotiate prices?

Contracts already concluded, such as orders already accepted and supply schedules with agreed prices for a certain period, are binding and must be fulfilled according to the original agreements.

In the absence of specific clauses in the contract, the party affected by the tariff is therefore obliged to comply with the previously agreed price and give fulfillment to the agreement.

The parties are free to renegotiate future contracts, e.g.

- the seller may give a discount to lessen the impact of the duty affecting the buyer-importer, or

- the buyer may agree to a price increase to compensate for a duty that the seller has paid to import a component or semi-finished product into his country, and then export the finished product

but this does not affect the validity of contracts already negotatied, which remain binding.

The situation is particularly delicate for companies in the middle of the supply chain, such as those who import raw materials or components from abroad (potentially subject to tariffs, including double duties in the case of repeated import and export) and resell the semi-finished or finished products, since they are not entitled to pass the cost on to the following link in the supply chain, unless this was expressly provided for in the contract with the customer.

What can be done in case of imposition of future duties affecting foreign suppliers or customers?

It is advisable to expressly provide for the right to renegotiate prices, if necessary by adding an addendum to the original agreement. This can be achieved, for example, by a clause providing that in case future events, including any duties, cause an increase in the overall cost of the product above a certain threshold (e.g., 10 percent), the party affected by the tariffs has the right to initiate a renegotiation of the price and, in the event of a failure to agree, can withdraw from the contract.

An example of a clause might be as follows:

Import Duties Adjustment

“If any new import duties, tariffs, or similar governmental charges are imposed after the conclusion of this Contract, and such measures increase a Party’s costs exceeding X% of the agreed price of the Products, the affected Party shall have the right to request an immediate renegotiation of the price. The Parties shall engage in good faith negotiations to reach a fair adjustment of the contractual price to reflect the increased costs.

If the Parties fail to reach an agreement within [X] days from the affected Party’s request for renegotiation, the latter shall have the right to terminate this Contract with [Y] days‘ written notice to other Party, without liability for damages, except for the fulfillment of obligations already accrued.”

‘’Made in Italy” is synonymous of high productive and aesthetic quality and represents an added value, in the international market, for different kind of products, from foodstuffs to clothing, automotive and furniture. In recent years, in Italy, a number of initiatives have been taken at the regulatory level to ensure its promotion, valorization and protection.

In 2024 came into force law no. 206/2023, referred to as the ‘New Made in Italy Law’, followed on 3 July 2024 by the related implementing Decree, by which the Ministry of Enterprise and Made in Italy (hereinafter the ‘Ministry’) introduced relevant provisions including the ones related to an official mark attesting the Italian origin of goods, the fight against counterfeiting (in particular in criminal law), and the promotion of the use of blockchain technology to protect production chains.

Among the new measures, there are specific rules for the protection of trademarks – with at least 50 years of registration or use in Italy – of particular national interest and value (hereinafter “Trademark/s”). The aim of such provisions is to safeguard the heritage represented by Italian trademarks with a long-standing presence on the market, preventing their extinction and guaranteeing their use by companies linked to the Italian territory.

Measures to guarantee the continuity

In order to protect the Trademarks, two distinct possibilities are envisaged

- Notification by companies

The first consists of the takeover by the Ministry of the ownership of Trademarks of companies that will cease their activities. In this regard, the Decree provides that a company owner or licensee of a trademark registered for at least 50 years, or for which it is possible to prove continuous use for at least 50 years, intending to cease its activity definitively, must notify the Ministry in advance of the plan to cease its activity, indicating, in particular, the economic, financial or technical reasons that impose the cessation. Upon receipt of this notification, the Ministry is entitled to take over ownership of the trademark without charge if the trademark has not been assigned for consideration by the owner or licensee company.

This procedure, in particular, is newly implemented, being applicable as of 2 December 2024.

- Revocation for non-use

The second possibility concerns Trademarks suspected of not being used for at least 5 years. In such case, the Ministry may file before the Italian Patent and Trademark Office an application for revocation for non-use and, if the application is granted, proceed with registering the Trademark in its name.

Trademarks of national interest owned by the Ministry will be announced on its Web site https://www.mimit.gov.it/it/impresa/competitivita-e-nuove-imprese/proprieta-industriale/marchi-di-interesse-storico/elenco-marchi.

As of 27 January 2025, one month after the applicability of the procedures at issue in the list are the following:

- INNOCENTI – Application number 302023000141171

- AUTOBIANCHI – Application number 302023000141189

Free licences for Italian or foreign companies wishing to invest in Italy

The Ministry is authorized to use the Trademarks, licensing them exclusively in favor of companies, including foreign ones, that intend to invest in Italy or transfer production activities located abroad to Italy.

In particular, Italian and foreign companies planning to produce in Italy may apply for a licence to use the above-mentioned Trademarks. The application shall contain specific details regarding the planned investment project, with a focus on the employment impact of the same.

Should the Ministry accept the application, the company will be granted a 10-year free licence, renewable on condition that the company maintains production activities within the national borders.

It is to be noted that, in the event that the company interrupts its activities or relocates its plants outside the Italian territory, the licence contract may be terminated immediately.

What’s next?

The recent regulatory measures are aimed, on the one hand, at keeping alive traditional brands that have been used in Italy for many years and, on the other hand, at allowing Italian and foreign companies to benefit from the incentive of free licences, if they decide to produce in Italy.

It will be interesting to monitor the business developments of these provisions in the coming months, in which the list of Trademarks owned by the Ministry will become longer.

“This agreement is not just an economic opportunity. It is a political necessity.” In the current geopolitical context of growing protectionism and significant regional conflicts, Ursula von der Leyen’s statement says a lot.

Even though there is still a long way to go before the agreement is approved internally in each bloc and comes into force, the milestone is highly significant. It took 25 years from the start of negotiations between Mercosur and the European Union to reach a consensus text. The impacts will be considerable. Together, the blocs represent a GDP of over 22 trillion dollars, and are home to over 700 million people.

Our aim here is to highlight, in a simplified manner, the most important information about the agreement’s content and its progress, which we will update here at each stage.

What is it?

The agreement was signed as a trade treaty, with the main goal of reducing import and export tariffs, eliminating bureaucratic barriers, and facilitating trade between Mercosur countries and European Union members. Additionally, the pact includes commitments in areas such as sustainability, labor rights, technological cooperation, and environmental protection.

Mercosur (Southern Common Market) is an economic bloc created in 1991 by Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Now, Bolivia and Chile participate as associated members, accessing some trade agreements, but not fully integrated into the common market. On the other hand, the European Union, with its 27 members (20 of which have adopted the common currency), is a broader union with greater economic and social integration compared to Mercosur.

What does the EU Mercosur agreement include?

Trade in goods:

- Reduction or elimination of tariffs on products traded between the blocs, such as meat, grains, fruits, automobiles, wines, and dairy products (the expected reduction will affect over 90% of the traded goods between the blocks).

- Easier access to European high-tech and industrialized products.

Trade in services:

- Expands access to financial services, telecommunications, transportation, and consulting for businesses in both blocs.

Movement of people:

- Provides facilities for temporary visas for qualified workers, such as technology professionals and engineers, promoting talent exchange.

- Encourages educational and cultural cooperation programs.

Sustainability and environment:

- Includes commitments to combat deforestation and meet the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change.

- Provides penalties for violations of environmental standards.

Intellectual property and regulations:

- Protects geographical indications for European cheese, wines, and South American coffee and cachaça.

- Harmonizes regulatory standards to reduce bureaucracy and avoid technical barriers.

Labor rights:

- Commitment to decent working conditions and compliance with International Labor Organization (ILO) standards.

Which benefits to expect?

- Access to new markets: Mercosur companies will have easier access to the European market, which has more than 450 million consumers, while European products will become more competitive in South America.

- Costs reduction: The elimination or reduction of tariffs could lower the prices of products such as wines, cheese, and automobiles and boost South American exports of meat, grains, and fruits.

- Strengthened diplomatic relations: The agreement symbolizes a bridge of cooperation between two regions historically connected by cultural and economic ties.

What’s next?

The signing is only the first step. For the agreement to come into force, it must be ratified by both blocs, and the approval process is quite distinct between them, since Mercosur does not have a common Council or Parliament.

In the European Union, the ratification process involves multiple institutional steps:

- Council of the European Union: Ministers from the member states will discuss and approve the text of the agreement. This step is crucial, as each country has representation and may raise specific national concerns.

- European Parliament: After approval by the Council, the European Parliament, composed of elected deputies, votes to ratify the agreement. The debate at this stage may include environmental, social, and economic impacts.

- National Parliaments: In cases where the agreement affects shared competencies between the bloc and member states (such as environmental regulations), it must also be approved by the parliaments of each member country. This can be challenging, given that countries like France and Ireland have already expressed specific concerns about agricultural and environmental issues.

In Mercosur, the approval depends on each member country:

- National Congresses: The agreement text is submitted to the parliaments of Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Each congress evaluates independently, and approval depends on the political majority in each country.

- Political Context: Mercosur countries have diverse political realities. In Brazil, for example, environmental issues can spark heated debates, while in Argentina, the impact on agricultural competitiveness may be the focus of discussion.

- Regional Coordination: Even after national approval, it is necessary to ensure that all Mercosur members ratify the agreement, as the bloc acts as a single negotiating entity.

Stay tuned: you will find the update here as the processes advance.

Ignacio Alonso recently posted his interesting article “Spain – Can an influencer be considered a “commercial agent”” where he discussed the elements that – in some specific circumstances – could lead to considering an influencer as a commercial agent, with the consequent protections that Directive 86/653/CE and the individual legislation of the EU Member States offer, and the related costs to be borne by the companies that hire them.

Ignacio also mentioned a recent ruling issued by an Italian court (“Tribunale di Roma, Sezione Lavoro, judgment of March 4th 2024 n.2615”) which caused a lot of interest here, precisely because it expressly recognized the qualification of commercial agents to some influencers.

Inspired by Ignacio’s interesting contribution, this article will explain this ruling in more detail and draw some indications that may be useful for companies that want to hire influencers in Italy.

The case arose from an inspection conducted by ENASARCO (social security institution for Italian commercial agents) at a company that markets food supplements online and which had hired some influencers to promote its products on social media.

The contracts provided for the influencers’ commitment to promote the company’s branded products on its behalf on social media networks and on the websites owned by the influencer.

In promoting the products, the influencers indicated their personalized discount code for the followers to use. With this discount code, the company could track the orders from the influencer’s followers and, therefore, originated from him, paying him commissions as a percentage of these sales once paid for. The influencer also received fixed compensation for the posts he published.

The compensation was invoiced monthly, and in fact, the influencers issued dozens of invoices over the years, accruing substantial compensation.

The contracts were stipulated for an indefinite period.

The inspector had considered that the relationships between the company and the influencers were to be classified as a commercial agency and had therefore imposed fines on the company for failure to register with ENASARCO and pay the contributions for social security and termination indemnity for rather high amounts.

The administrative appeal was rejected, therefore the company took legal action before the Court of Rome (Labour and Social Security section), competent for cases against ENASARCO, to obtain the annulment of the fines.

The company’s defense was based on the following circumstances, among others:

- the online marketing activities were only ancillary for the influencers (in fact, they were mostly personal trainers or athletes)

- they promoted the products only occasionally

- they actually had no direct contact with customers, so they did not actually promote sales but only did some advertising

- they did not have an assigned area or any obligations typical of the agent (e.g. exclusivity).

The Court of Rome rejected the company’s arguments, stating that the relationships between the company and the influencers were indeed to be considered as agency agreements, thus confirming ENASARCO’s claims.

These were the main points in the courts’ reasoning:

- the purpose of the contracts stipulated between the parties was not mere advertising but the influencer’s promotion of sales of the company’s products to his followers, as confirmed by the discount code mechanism. Promotional activity can in fact, be performed in various ways, in this case, also considering the peculiarity of the web and social networks

- there was an “assigned area”, which the Court identified precisely in the community of the influencer’s followers (the area is not necessarily geographical but can also be identified with a group or category of customers)

- the relationship between the parties had proven to be stable and continuous, as evidenced by the quantity and regularity of the invoices for commissions issued by the influencers over the years for an indeterminate series of deals, documented with regular account statements

- the contract had an indefinite duration, which highlighted the parties’ desire to establish a stable and long-lasting relationship.

What considerations can be drawn from this ruling?

First of all, the scope of the agency contract is becoming much broader than in the past.

Nowadays, the traditional activity of the agent who physically goes to customers to solicit sales, collect orders, and transmit them to the principal is no longer the only method to promote sales. The qualification as an agent can also be recognized by other figures who, in different ways – taking into account the specific industrial sector, the technology developments, etc.- still carry out activities to increase sales.

What matters is the agreed purpose of the collaboration, if it is aimed at sales, and whether the activity actually carried out by the collaborator is consistent with and aimed at this purpose.

These aspects need to be carefully considered when studying and drafting the contract.

Other key requirements for establishing an agency relationship are the “stability and continuity”, to be distinguished from occasional activity.

A relationship may begin as an occasional collaboration, but over time, it can evolve and become an ongoing relationship, generating significant turnover for both parties. This could be enough to qualify the relationship as an agency.

Therefore, it is necessary to monitor the progress of the relationship and sometimes evaluate the conversion of an occasional relationship into an agency if circumstances suggest so.

As can be seen from the judgment of the court of Rome, relationships with Italian agents operating in Italy (but in some cases also with Italian agents operating abroad) must be registered with ENASARCO (unlike occasional relationships), and the related contributions must be paid, otherwise the principal may be fined.

Naturally, qualifying a relationship with an influencer as an agency agreement also means that the influencer enjoys all the protections provided for by Directive 653/86 and the legislation implementing it (in Italy, articles 1742 and following of the Civil Code and the applicable collective bargaining agreement), including, for example, the right to termination notice and termination indemnity.

A company intending to appoint an independent person with commercial tasks in Italy, including now also influencers under certain conditions, will have to take all of this into account. Of course, the case may be different if the influencer does not carry out stable and continuous promotional activities and is not remunerated with commissions on the orders generated by this activity.

I am unaware whether the ruling analysed in this article has been or will be appealed. If appealed, staying updated on the developments will certainly be interesting.

Summary: Corporate fraud has taken new and insidious forms in the digital age. One of these puts multinational groups in the crosshairs: it is the so-called “CEO Fraud.” This type of fraud is based on the fraudulent use of the identity of top corporate figures, such as CEOs or board chairmen. The modus operandi is devious: the fraudsters pose as the CEO or a senior executive of the multinational group and directly contact the Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) of the subsidiaries or affiliates, simulating a nonexistent confidential investment transaction to induce them to make urgent transfers to foreign bank accounts.

Background and dynamics of the CEO Fraud

CEO Fraud is a form of scam in which criminals impersonate senior management figures to trick employees, usually CFOs, into transferring funds into bank accounts controlled by the fraudsters. The choice to use the identities of apex figures such as CEOs lies in their perceived authority and ability to order even large payments, requested urgently and with instructions for strict confidentiality, without raising immediate suspicion.

Fraudsters adopt various communication tools to make their fraud attempts credible: at the starting point is usually a data breach, which allows criminals to gain access to the contact details of the CEO or CFO (email, landline phone number, cell phone number, whatsapp or social media accounts) or other people within the administrative office with operational powers over bank accounts.

Sometimes knowledge of this information does not even require illegitimate access to the company’s computer systems because those targeted by the scam spontaneously make this information public, for example, by indicating it on their profiles on the company website or by publicly displaying contacts on profiles in social media accounts (LinkedIn, Facebook, etc.) or even on presentations, business cards and company brochures in the context of public meetings.

Still other times, scammers do not even need to appropriate all the data of the CEO they want to impersonate, but only the recipient’s, and then claim that they are using a personal account with a different number or email address than those usually attributable to the real CEO.

Contacts are typically made as follows:

- WhatsApp and SMS: The use of messages allows for immediate and personal communication, often perceived as legitimate by recipients. The fake CEO sends a message to the CFO using a cell phone number from the country where the parent company is based (e.g., +34 in the case of Spain), writing that it is his personal phone number and using a portrait photo of the real CEO in the WhatsApp profile, which reinforces the perception that the fraudster is the real CEO.

- Phone calls: after the initial contact via text message, a phone call often follows, which may be either directly from the fake CEO or from a self-styled lawyer or consultant instructed by the CEO to give the CFO the necessary information about the fake investment transaction and instructions to proceed with the urgent payment.

- Email: as an alternative to or in addition to texts and phone calls, communications may also go through emails, often indistinguishable from authentic ones, in which text formats, company logos, signatures, etc. are scrupulously replicated.

This is possible through various email spoofing techniques in which the sender’s email address is altered to appear as if the rightful owner sent the email. Basically, it is like someone sending a postal letter by putting a different address on the back of the envelope to disguise the true origin of the missive. In our case, this means that the CFO receives an email that-at first glance-appears to come from the CEO and not the scammer.

We also cannot rule out the possibility of fraudsters taking advantage of security holes in corporate systems, such as directly accessing internal chats within the organization.

In addition, the increasing popularity of morphing tools (i.e., creating images with human likenesses that can be traced back to real people) may make it even more difficult to unmask the scammer: to messages and phone calls we could, in fact, add video messages or even video lectures apparently given by the real CEO.

The (fake) takeover of a competitor company in Europe

Let us look at a real-life example of CEO Fraud to illustrate the practical ways in which these frauds are organized.

Scammers create a fake WhatsApp profile of the self-styled CEO of a multinational group based in Spain, using a Spanish phone number and reproducing the profile photo of the authentic CEO.

A message is sent through the fake account to the CFO of a subsidiary in Italy, announcing that a confidential investment transaction is underway to acquire a company in Portugal. This will require transferring a large sum to a Portuguese company the following day at a local bank.

The message stresses the importance of keeping the transaction strictly confidential, which is why the CFO cannot disclose the payment request to anyone: a confidentiality agreement from a (fake) law firm is even emailed before payment is made, which the CFO is persuaded to sign and return to the phantom lawyer in charge of the transaction.

Instructions for proceeding with the transfer are emailed to the CFO, again stressing the urgency of making the payment on the same day.

The day after arranging the transfer, having heard nothing more from the fake CEO, the CFO arranges to contact him at his corporate phone number and discovers the scam: by that time, however, it is too late because the sums have already been transferred by the criminals to one or more current accounts in foreign banks, making it very difficult, if not impossible, to trace the funds.

The main features of CEO fraud

- Persuasion: the fact that fraudsters impersonate apex figures and make the CFO feel invested in important duties generates in the victim a desire to please superiors and to let their guard down.

- Pressure: fraudsters instil a great sense of urgency, demanding payments extremely quickly and intimating secrecy about the transaction; this causes the victim to act without thinking, trying to be as efficient as possible.

- Speed: It is good to know that a request for an urgent wire transfer cannot be withdrawn, or can be withdrawn by recall only under extremely tight deadlines; fraudsters take advantage of this to pocket the sums at banks that are not too scrupulous or to move them elsewhere, at most within a few days.

How to prevent these scams

CEO Fraud schemes can be very sophisticated, but they often have signs that, if recognized, can stop a scam before it causes irreparable damage.

The main clues are the atypical modes of contact (whatsapp, phone calls, emails from the fake CEO’s personal accounts), the request for strict confidentiality about the transaction, the urgency with which large sums are requested, the fact that the transfer is to be made to banks abroad, and the involvement of companies or individuals never previously mentioned.

To prevent scams such as CEO Fraud, corporate training of employees on how to recognize and respond to scams is crucial; it is also essential to have robust internal security procedures in place.

- First, an essential and basic precaution is to adopt verification systems that scan e-mail messages for viruses and flag the origin of the e-mail from an account outside the corporate organization.

- Second, it is critical that companies implement clear processes for payments to third parties, especially if the arrangements are different from the company’s standard operations. One way to do this is to provide value limits on the powers of disposition over current account operations, beyond which dual signatures with another director are required.

- Finally, and generally, it is good to adopt all the rules of common sense and diligence in analyzing the case. Better to do one more internal check than one less; for example, in the case of a particularly realistic but nonetheless unusual request, forwarding the exchange with the alleged scammer to the address we believe to be real and asking for further confirmation in the forward email, rather than responding directly in the email loop, allows us to tell if the sender is bogus.

Legal actions to recover funds.

After the fraud is discovered, it is crucial to act quickly to increase the chances of recovering lost funds and prosecuting those responsible.

Possible Legal Actions

Prompt notification to the company’s bank to block or recall the wire payment, in addition to a timely criminal complaint in the country where the bank receiving the payment is based, are immediate steps that can help contain the damage and begin the recovery process.

In fact, in many countries, the pattern of CEO Fraud is well known, and specialized law enforcement units have the tools to move in a timely manner following a report of the crime.

Criminal investigations in the country of payment destination also allow for verification that they are the account holders and the people involved in the scam attempt, in some cases leading to the arrest of those responsible.

After attempting to obtain a freeze on the transfer or funds, it may then be possible to assess the behavior of the banking institutions involved in the affair, particularly to verify whether the beneficiary bank properly complied with its obligations under anti-money laundering regulations, which impose precise obligations to verify customers and the origin of funds.

Conclusions

CEO Fraud is a significant threat to companies of all sizes and industries, made possible and amplified by modern technologies and the globalization of financial markets. Companies must remain vigilant and proactive, continually updating their security procedures to keep pace with fraudsters’ evolving techniques.

Investment in training, technology and consulting is not just a protective measure, but a strategic necessity for business operations.

Finally, if the scam is successfully carried out, it is crucial to take prompt action to try to block the funds before they are moved to bank accounts in other countries and thus made untraceable.

Summary

To avoid disputes with important suppliers, it is advisable to plan purchases over the medium and long term and not operate solely on the basis of orders and order confirmations. Planning makes it possible to agree on the duration of the ‘supply agreement, minimum volumes of products to be delivered and delivery schedules, prices, and the conditions under which prices can be varied over time.

The use of a framework purchase agreement can help avoid future uncertainties and allows various options to be used to manage commodity price fluctuations depending on the type of products , such as automatic price indexing or agreement to renegotiate in the event of commodity fluctuations beyond a certain set tolerance period.

I read in a press release: “These days, the glass industry is sending wine companies new unilateral contract amendments with price changes of 20%…”

What can one do to avoid the imposition of price increases by suppliers?

- Know your rights and act in an informed manner

- Plan and organise your supply chain

Does my supplier have the right to increase prices?

If contracts have already been concluded, e.g., orders have already been confirmed by the supplier, the answer is often no.

It is not legitimate to request a price change. It is much less legitimate to communicate it unilaterally, with the threat of cancelling the order or not delivering the goods if the request is not granted.

What if he tells me it is force majeure?

That’s wrong: increased costs are not a force majeure but rather an unforeseen excessive onerousness, which hardly happens.

What if the supplier canceled the order, unilaterally increased the price, or did not deliver the goods?

He would be in breach of contract and liable to pay damages for violating his contractual obligations.

How can one avoid a tug-of-war with suppliers?

The tools are there. You have to know them and use them.

It is necessary to plan purchases in the medium term, agreeing with suppliers on a schedule in which are set out:

- the quantities of products to be ordered

- the delivery terms

- the durationof the agreement

- the pricesof the products or raw materials

- the conditions under which prices can be varied

There is a very effective instrument to do so: a framework purchase agreement.

Using a framework purchase agreement, the parties negotiate the above elements, which will be valid for the agreed period.

Once the agreement is concluded, product orders will follow, governed by the framework agreement, without the need to renegotiate the content of individual deliveries each time.

For an in-depth discussion of this contract, see this article.

- “Yes, but my suppliers will never sign it!”

Why not? Ask them to explain the reason.

This type of agreement is in the interest of both parties. It allows planning future orders and grants certainty as to whether, when, and how much the parties can change the price.

In contrast, acting without written agreements forces the parties to operate in an environment of uncertainty. Suppliers can request price increases from one day to the next and refuse supply if the changes are not accepted.

How are price changes for future supplies regulated?

Depending on the type of products or services and the raw materials or energy relevant in determining the final price, there are several possibilities.

- The first option is to index the price automatically. E.g., if the cost of a barrel of Brent oil increases/decreases by 10%, the party concerned is entitled to request a corresponding adjustment of the product’s price in all orders placed as of the following week.

- An alternative is to provide for a price renegotiation in the event of a fluctuation of the reference commodity. E.g., suppose the LME Aluminium index of the London Stock Exchange increases above a certain threshold. In that case, the interested party may request a price renegotiationfor orders in the period following the increase.

What if the parties do not agree on new prices?

It is possible to terminate the contract or refer the price determination to a third party, who would act as arbitrator and set the new prices for future orders.

Summary

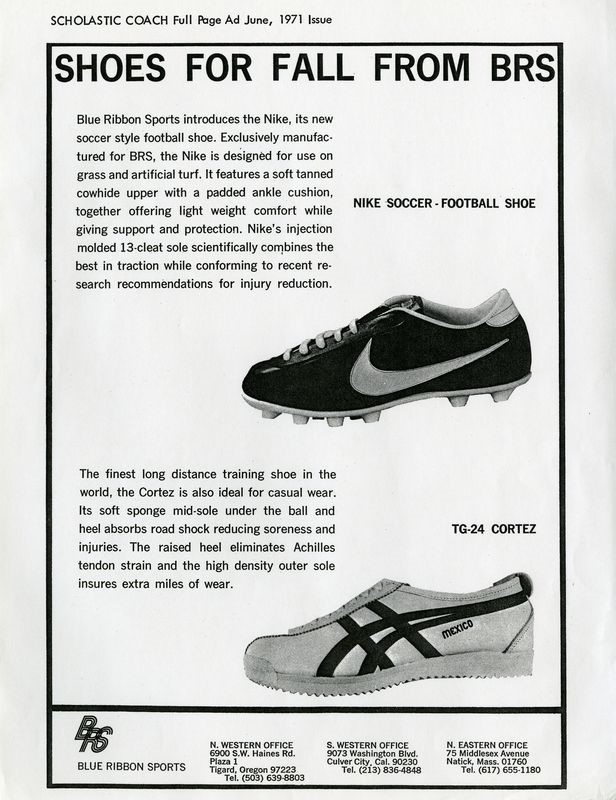

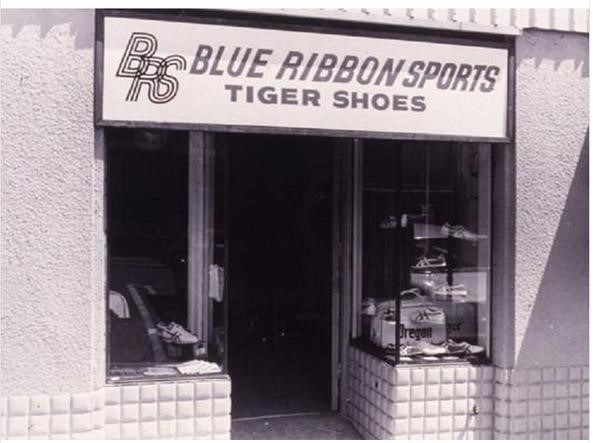

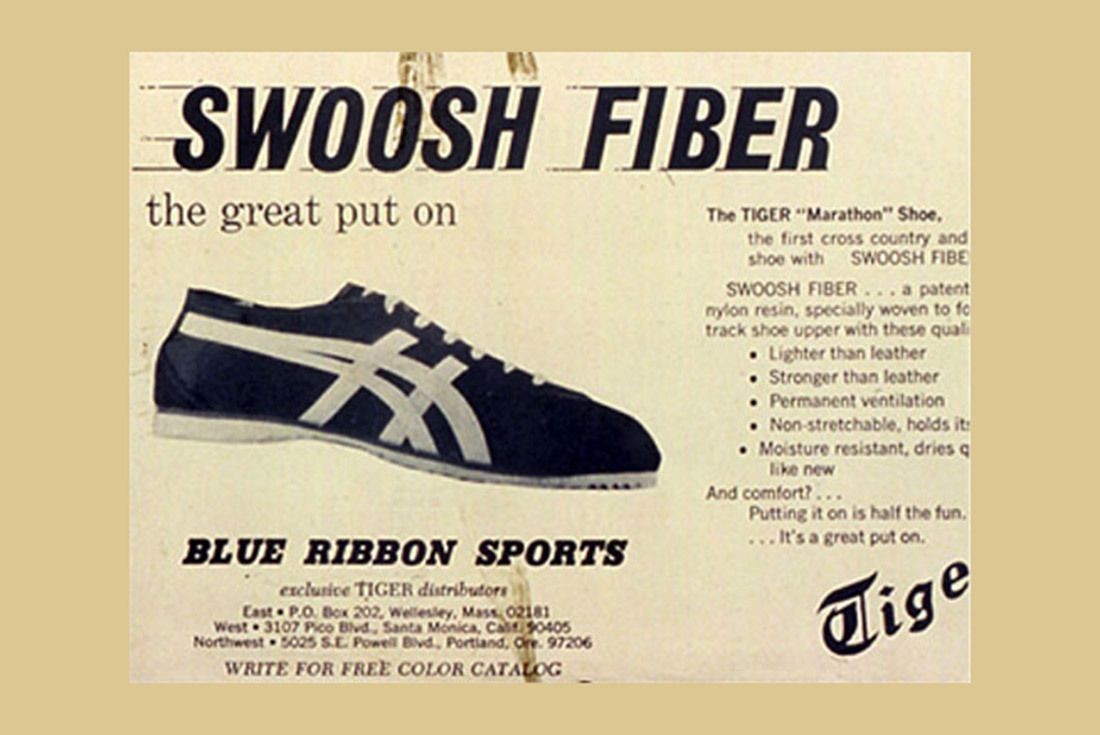

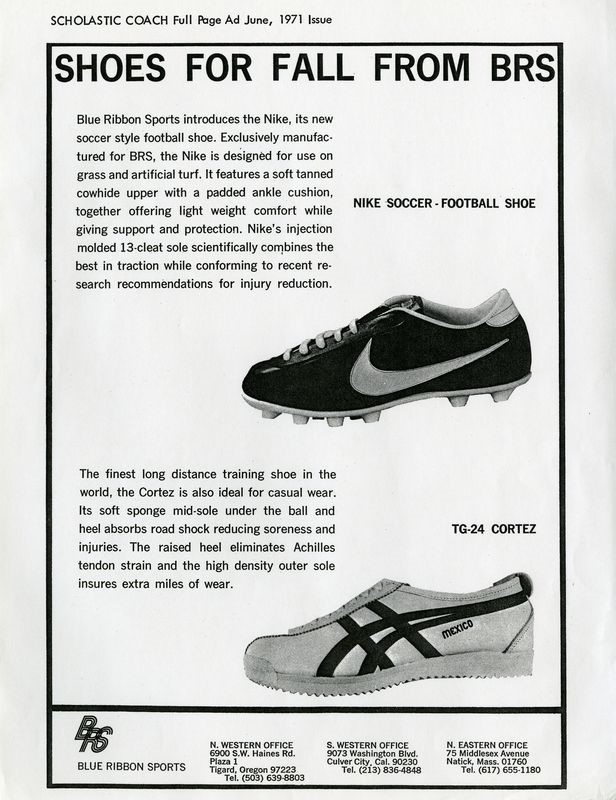

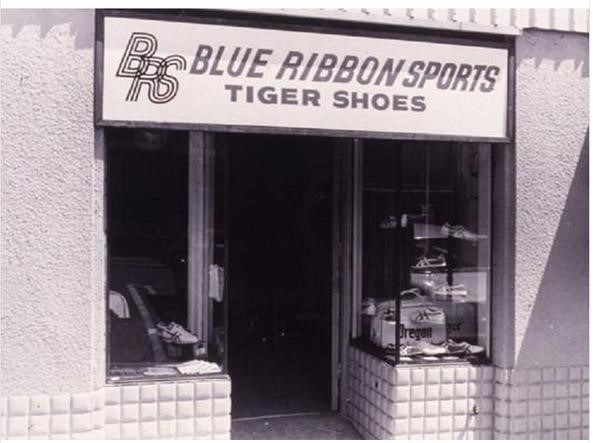

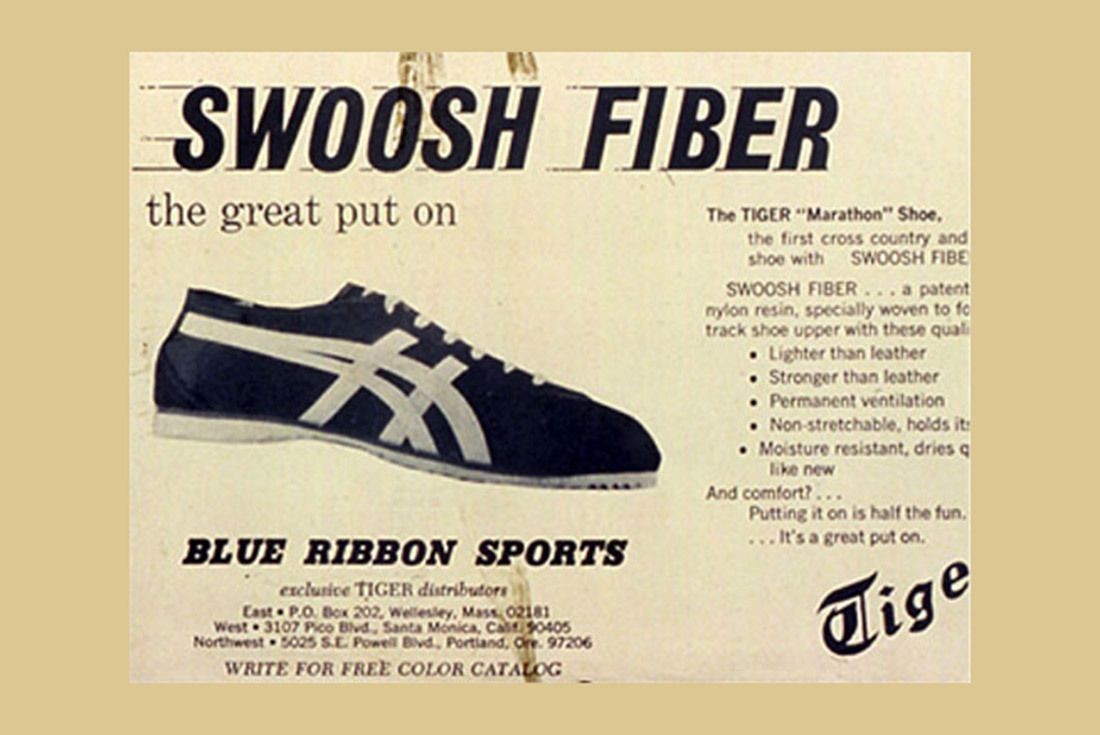

Phil Knight, the founder of Nike, imported the Japanese brand Onitsuka Tiger into the US market in 1964 and quickly gained a 70% share. When Knight learned Onitsuka was looking for another distributor, he created the Nike brand. This led to two lawsuits between the two companies, but Nike eventually won and became the most successful sportswear brand in the world. This article looks at the lessons to be learned from the dispute, such as how to negotiate an international distribution agreement, contractual exclusivity, minimum turnover clauses, duration of the contract, ownership of trademarks, dispute resolution clauses, and more.

What I talk about in this article

- The Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger dispute and the birth of Nike

- How to negotiate an international distribution agreement

- Contractual exclusivity in a commercial distribution agreement

- Minimum Turnover clauses in distribution contracts

- Duration of the contract and the notice period for termination

- Ownership of trademarks in commercial distribution contracts

- The importance of mediation in international commercial distribution agreements

- Dispute resolution clauses in international contracts

- How we can help you

The Blue Ribbon vs Onitsuka Tiger dispute and the birth of Nike

Why is the most famous sportswear brand in the world Nike and not Onitsuka Tiger?

Shoe Dog is the biography of the creator of Nike, Phil Knight: for lovers of the genre, but not only, the book is really very good and I recommend reading it.

Moved by his passion for running and intuition that there was a space in the American athletic shoe market, at the time dominated by Adidas, Knight was the first, in 1964, to import into the U.S. a brand of Japanese athletic shoes, Onitsuka Tiger, coming to conquer in 6 years a 70% share of the market.

The company founded by Knight and his former college track coach, Bill Bowerman, was called Blue Ribbon Sports.

The business relationship between Blue Ribbon-Nike and the Japanese manufacturer Onitsuka Tiger was, from the beginning, very turbulent, despite the fact that sales of the shoes in the U.S. were going very well and the prospects for growth were positive.

When, shortly after having renewed the contract with the Japanese manufacturer, Knight learned that Onitsuka was looking for another distributor in the U.S., fearing to be cut out of the market, he decided to look for another supplier in Japan and create his own brand, Nike.

Upon learning of the Nike project, the Japanese manufacturer challenged Blue Ribbon for violation of the non-competition agreement, which prohibited the distributor from importing other products manufactured in Japan, declaring the immediate termination of the agreement.

In turn, Blue Ribbon argued that the breach would be Onitsuka Tiger’s, which had started meeting other potential distributors when the contract was still in force and the business was very positive.

This resulted in two lawsuits, one in Japan and one in the U.S., which could have put a premature end to Nike’s history.

Fortunately (for Nike) the American judge ruled in favor of the distributor and the dispute was closed with a settlement: Nike thus began the journey that would lead it 15 years later to become the most important sporting goods brand in the world.

Let’s see what Nike’s history teaches us and what mistakes should be avoided in an international distribution contract.

How to negotiate an international commercial distribution agreement

In his biography, Knight writes that he soon regretted tying the future of his company to a hastily written, few-line commercial agreement at the end of a meeting to negotiate the renewal of the distribution contract.

What did this agreement contain?

The agreement only provided for the renewal of Blue Ribbon’s right to distribute products exclusively in the USA for another three years.

It often happens that international distribution contracts are entrusted to verbal agreements or very simple contracts of short duration: the explanation that is usually given is that in this way it is possible to test the commercial relationship, without binding too much to the counterpart.

This way of doing business, though, is wrong and dangerous: the contract should not be seen as a burden or a constraint, but as a guarantee of the rights of both parties. Not concluding a written contract, or doing so in a very hasty way, means leaving without clear agreements fundamental elements of the future relationship, such as those that led to the dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger: commercial targets, investments, ownership of brands.

If the contract is also international, the need to draw up a complete and balanced agreement is even stronger, given that in the absence of agreements between the parties, or as a supplement to these agreements, a law with which one of the parties is unfamiliar is applied, which is generally the law of the country where the distributor is based.

Even if you are not in the Blue Ribbon situation, where it was an agreement on which the very existence of the company depended, international contracts should be discussed and negotiated with the help of an expert lawyer who knows the law applicable to the agreement and can help the entrepreneur to identify and negotiate the important clauses of the contract.

Territorial exclusivity, commercial objectives and minimum turnover targets

The first reason for conflict between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger was the evaluation of sales trends in the US market.

Onitsuka argued that the turnover was lower than the potential of the U.S. market, while according to Blue Ribbon the sales trend was very positive, since up to that moment it had doubled every year the turnover, conquering an important share of the market sector.

When Blue Ribbon learned that Onituska was evaluating other candidates for the distribution of its products in the USA and fearing to be soon out of the market, Blue Ribbon prepared the Nike brand as Plan B: when this was discovered by the Japanese manufacturer, the situation precipitated and led to a legal dispute between the parties.

The dispute could perhaps have been avoided if the parties had agreed upon commercial targets and the contract had included a fairly standard clause in exclusive distribution agreements, i.e. a minimum sales target on the part of the distributor.

In an exclusive distribution agreement, the manufacturer grants the distributor strong territorial protection against the investments the distributor makes to develop the assigned market.

In order to balance the concession of exclusivity, it is normal for the producer to ask the distributor for the so-called Guaranteed Minimum Turnover or Minimum Target, which must be reached by the distributor every year in order to maintain the privileged status granted to him.

If the Minimum Target is not reached, the contract generally provides that the manufacturer has the right to withdraw from the contract (in the case of an open-ended agreement) or not to renew the agreement (if the contract is for a fixed term) or to revoke or restrict the territorial exclusivity.

In the contract between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger, the agreement did not foresee any targets (and in fact the parties disagreed when evaluating the distributor’s results) and had just been renewed for three years: how can minimum turnover targets be foreseen in a multi-year contract?

In the absence of reliable data, the parties often rely on predetermined percentage increase mechanisms: +10% the second year, + 30% the third, + 50% the fourth, and so on.

The problem with this automatism is that the targets are agreed without having available the real data on the future trend of product sales, competitors’ sales and the market in general, and can therefore be very distant from the distributor’s current sales possibilities.

For example, challenging the distributor for not meeting the second or third year’s target in a recessionary economy would certainly be a questionable decision and a likely source of disagreement.

It would be better to have a clause for consensually setting targets from year to year, stipulating that targets will be agreed between the parties in the light of sales performance in the preceding months, with some advance notice before the end of the current year. In the event of failure to agree on the new target, the contract may provide for the previous year’s target to be applied, or for the parties to have the right to withdraw, subject to a certain period of notice.

It should be remembered, on the other hand, that the target can also be used as an incentive for the distributor: it can be provided, for example, that if a certain turnover is achieved, this will enable the agreement to be renewed, or territorial exclusivity to be extended, or certain commercial compensation to be obtained for the following year.

A final recommendation is to correctly manage the minimum target clause, if present in the contract: it often happens that the manufacturer disputes the failure to reach the target for a certain year, after a long period in which the annual targets had not been reached, or had not been updated, without any consequences.

In such cases, it is possible that the distributor claims that there has been an implicit waiver of this contractual protection and therefore that the withdrawal is not valid: to avoid disputes on this subject, it is advisable to expressly provide in the Minimum Target clause that the failure to challenge the failure to reach the target for a certain period does not mean that the right to activate the clause in the future is waived.

The notice period for terminating an international distribution contract

The other dispute between the parties was the violation of a non-compete agreement: the sale of the Nike brand by Blue Ribbon, when the contract prohibited the sale of other shoes manufactured in Japan.

Onitsuka Tiger claimed that Blue Ribbon had breached the non-compete agreement, while the distributor believed it had no other option, given the manufacturer’s imminent decision to terminate the agreement.

This type of dispute can be avoided by clearly setting a notice period for termination (or non-renewal): this period has the fundamental function of allowing the parties to prepare for the termination of the relationship and to organize their activities after the termination.

In particular, in order to avoid misunderstandings such as the one that arose between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger, it can be foreseen that during this period the parties will be able to make contact with other potential distributors and producers, and that this does not violate the obligations of exclusivity and non-competition.

In the case of Blue Ribbon, in fact, the distributor had gone a step beyond the mere search for another supplier, since it had started to sell Nike products while the contract with Onitsuka was still valid: this behavior represents a serious breach of an exclusivity agreement.

A particular aspect to consider regarding the notice period is the duration: how long does the notice period have to be to be considered fair? In the case of long-standing business relationships, it is important to give the other party sufficient time to reposition themselves in the marketplace, looking for alternative distributors or suppliers, or (as in the case of Blue Ribbon/Nike) to create and launch their own brand.

The other element to be taken into account, when communicating the termination, is that the notice must be such as to allow the distributor to amortize the investments made to meet its obligations during the contract; in the case of Blue Ribbon, the distributor, at the express request of the manufacturer, had opened a series of mono-brand stores both on the West and East Coast of the U.S.A..

A closure of the contract shortly after its renewal and with too short a notice would not have allowed the distributor to reorganize the sales network with a replacement product, forcing the closure of the stores that had sold the Japanese shoes up to that moment.

Generally, it is advisable to provide for a notice period for withdrawal of at least 6 months, but in international distribution contracts, attention should be paid, in addition to the investments made by the parties, to any specific provisions of the law applicable to the contract (here, for example, an in-depth analysis for sudden termination of contracts in France) or to case law on the subject of withdrawal from commercial relations (in some cases, the term considered appropriate for a long-term sales concession contract can reach 24 months).

Finally, it is normal that at the time of closing the contract, the distributor is still in possession of stocks of products: this can be problematic, for example because the distributor usually wishes to liquidate the stock (flash sales or sales through web channels with strong discounts) and this can go against the commercial policies of the manufacturer and new distributors.

In order to avoid this type of situation, a clause that can be included in the distribution contract is that relating to the producer’s right to repurchase existing stock at the end of the contract, already setting the repurchase price (for example, equal to the sale price to the distributor for products of the current season, with a 30% discount for products of the previous season and with a higher discount for products sold more than 24 months previously).

Trademark Ownership in an International Distribution Agreement

During the course of the distribution relationship, Blue Ribbon had created a new type of sole for running shoes and coined the trademarks Cortez and Boston for the top models of the collection, which had been very successful among the public, gaining great popularity: at the end of the contract, both parties claimed ownership of the trademarks.

Situations of this kind frequently occur in international distribution relationships: the distributor registers the manufacturer’s trademark in the country in which it operates, in order to prevent competitors from doing so and to be able to protect the trademark in the case of the sale of counterfeit products; or it happens that the distributor, as in the dispute we are discussing, collaborates in the creation of new trademarks intended for its market.

At the end of the relationship, in the absence of a clear agreement between the parties, a dispute can arise like the one in the Nike case: who is the owner, producer or distributor?

In order to avoid misunderstandings, the first advice is to register the trademark in all the countries in which the products are distributed, and not only: in the case of China, for example, it is advisable to register it anyway, in order to prevent third parties in bad faith from taking the trademark (for further information see this post on Legalmondo).

It is also advisable to include in the distribution contract a clause prohibiting the distributor from registering the trademark (or similar trademarks) in the country in which it operates, with express provision for the manufacturer’s right to ask for its transfer should this occur.

Such a clause would have prevented the dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger from arising.

The facts we are recounting are dated 1976: today, in addition to clarifying the ownership of the trademark and the methods of use by the distributor and its sales network, it is advisable that the contract also regulates the use of the trademark and the distinctive signs of the manufacturer on communication channels, in particular social media.

It is advisable to clearly stipulate that the manufacturer is the owner of the social media profiles, of the content that is created, and of the data generated by the sales, marketing and communication activity in the country in which the distributor operates, who only has the license to use them, in accordance with the owner’s instructions.

In addition, it is a good idea for the agreement to establish how the brand will be used and the communication and sales promotion policies in the market, to avoid initiatives that may have negative or counterproductive effects.

The clause can also be reinforced with the provision of contractual penalties in the event that, at the end of the agreement, the distributor refuses to transfer control of the digital channels and data generated in the course of business.

Mediation in international commercial distribution contracts

Another interesting point offered by the Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger case is linked to the management of conflicts in international distribution relationships: situations such as the one we have seen can be effectively resolved through the use of mediation.

This is an attempt to reconcile the dispute, entrusted to a specialized body or mediator, with the aim of finding an amicable agreement that avoids judicial action.

Mediation can be provided for in the contract as a first step, before the eventual lawsuit or arbitration, or it can be initiated voluntarily within a judicial or arbitration procedure already in progress.

The advantages are many: the main one is the possibility to find a commercial solution that allows the continuation of the relationship, instead of just looking for ways for the termination of the commercial relationship between the parties.

Another interesting aspect of mediation is that of overcoming personal conflicts: in the case of Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka, for example, a decisive element in the escalation of problems between the parties was the difficult personal relationship between the CEO of Blue Ribbon and the Export manager of the Japanese manufacturer, aggravated by strong cultural differences.

The process of mediation introduces a third figure, able to dialogue with the parts and to guide them to look for solutions of mutual interest, that can be decisive to overcome the communication problems or the personal hostilities.

For those interested in the topic, we refer to this post on Legalmondo and to the replay of a recent webinar on mediation of international conflicts.

Dispute resolution clauses in international distribution agreements

The dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger led the parties to initiate two parallel lawsuits, one in the US (initiated by the distributor) and one in Japan (rooted by the manufacturer).

This was possible because the contract did not expressly foresee how any future disputes would be resolved, thus generating a very complicated situation, moreover on two judicial fronts in different countries.

The clauses that establish which law applies to a contract and how disputes are to be resolved are known as “midnight clauses“, because they are often the last clauses in the contract, negotiated late at night.

They are, in fact, very important clauses, which must be defined in a conscious way, to avoid solutions that are ineffective or counterproductive.

How we can help you

The construction of an international commercial distribution agreement is an important investment, because it sets the rules of the relationship between the parties for the future and provides them with the tools to manage all the situations that will be created in the future collaboration.

It is essential not only to negotiate and conclude a correct, complete and balanced agreement, but also to know how to manage it over the years, especially when situations of conflict arise.

Legalmondo offers the possibility to work with lawyers experienced in international commercial distribution in more than 60 countries: write us your needs.

A case recently decided by the Italian Supreme Court clarifies what the risks are for those who sell their products abroad without having paid adequate attention to the legal part of the contract (Order, Sec. 2, No. 36144 of 2022, published 12/12/2022).

Why it’s important: in contracts, care must be taken not only with what is written, but also with what is not written, otherwise there is a risk that implied warranties of merchantability will apply, which may make the product unsuitable for use, even if it conforms to the technical specifications agreed upon in the contract.

The international sales contract and the first instance decision

A German company had sued an Italian company in Italy (Court of Chieti) to have it ordered to pay the sales price of two invoices for supplies of goods (steel).

The Italian purchasing company had defended itself by claiming that the two invoices had been deliberately not paid, due to the non-conformity of three previous deliveries by the same German seller. It then counterclaimed for a finding of defects and a reduction in the price, to be set off against the other party’s claim, as well as damages.

In the first instance, the Court of Chieti had partially granted both the German seller’s demand for payment (for about half of the claim) and the buyer’s counterclaim.

The court-appointed technical expertise had found that the steel supplied by the seller, while conforming to the agreed data sheet, had a very low silicon value compared to the values at other manufacturers’ steel; however, the trial judge ruled out this as a genuine defect.

The judgment of appeal

The Court of Appeals of L’Aquila, appealed to the second instance by the buyer, had reached a different conclusion than the Court of First Instance, significantly reducing the amount owed by the Italian buyer, for the following reasons:

- the regime of “implied warranties” under Article 35 of the Vienna Convention on the International Sale of Goods of 11.4.80 (“CISG,” ratified in both Italy and Germany) applied, as the companies had business headquarters in two different countries, both of which were parties to the Convention;

- in particular, the chemical composition of the steel supplied by the seller, while not constituting a “defect” in the product (i.e., an anomaly or imperfection) was nonetheless to be considered a “lack of conformity” within the meaning of Articles 35(2)(a) and 36(1) of the CISG, as it rendered the steel unsuitable for the use for which goods of the same kind would ordinarily serve (also known as “warranty of merchantability”).

The ruling of the Supreme Court

The German seller then appealed to the Supreme Court against the Court of Appeals’ ruling, stating in summary that, according to the CISG, the conformity or non-conformity of the goods must be assessed against what was agreed upon in the contract between the parties; and that the “warranty of merchantability” should apply only in the absence of a precise agreement of the parties on the characteristics that the product must have.

However, the seller’s defense continued, in this case the Italian buyer had sent a data sheet including a summary table of the various chemical elements, where it was stated that silicon should be present in a percentage not exceeding 0.45, but no minimum percentage was indicated.

So, the fact that the percentage of silicon was significantly lower than that found on average in steel from other suppliers could not be considered a conformity defect, since, at the contract negotiation stage, the parties exchanging the data sheet had expressly agreed only on the maximum values, thus not considering the minimum values relevant to conformity.

The Supreme Court, however, disagreed with this reasoning and essentially upheld the Court of Appeals’ ruling, rejecting the German seller’s appeal.

The Court recalled that, according to Article 35 first paragraph of the CISG, the seller must deliver goods whose quantity, quality and kind correspond to those stipulated in the contract and whose packaging and wrapping correspond to those stipulated in the contract; and that, for the second paragraph, “unless the parties agree otherwise, goods are in conformity with the contract only if: a) they are suitable for the uses for which goods of the same kind would ordinarily serve.”

Other guarantees are enumerated in paragraphs (b) to (d) of the same standard[1] . They are commonly referred to collectively as “implied warranties.”

The Court noted that the warranties in question, including the one of “merchantability” just referred to, do not stand subordinate or subsidiary to contractual covenants; on the contrary, they apply unless expressly excluded by the parties.

It follows that, according to the Supreme Court, any intention of the parties to a sales contract to disapply the warranty of merchantability must “result from a specific provision agreed upon by the parties.“

In the present case, although the data sheet that was part of the contractual agreements was analytical and had included among the chemical characteristics of the material the percentage of silicon, the fact that only a maximum percentage was indicated and not also the minimum percentage was not sufficient to exclude the fact that, by virtue of the “implied guarantee” of marketability, the minimum percentage should in any case conform to the average percentage of similar products existing on the market.

Since the “warranty of merchantability” had not been expressly excluded between the parties by a specific contractual clause, the conformity of the goods to the contract still had to be evaluated in consideration of this implied warranty as well.

Conclusions

What should businesses that sell abroad keep in mind?

- In contracts for the sale of goods between companies based in two different countries, the CISG automatically applies in many cases, in preference to the domestic law of either the seller’s country or the buyer’s country.

- The CISG contains very important rules for the relationship between sellers and buyers, on warranties of conformity of goods with the contract and buyer’s remedies for breach of warranties.

- One can modify or even exclude these rules by drafting appropriate contracts or general conditions in writing.

- Parties may agree not to apply all or some of the “implied warranties” (possibly replacing them with contractual warranties) just as they may exclude certain remedies (e.g., exclude or limit liability for damages, within certain limits). However, they must do so in clear and explicit clauses.

- For the “warranty of merchantability” not to apply, according to the reasoning of the Italian Supreme Court, it is not enough not to mention it in the contract.

- It is not sufficient to attach an analytical description of the characteristics of the goods to the contract to exclude certain characteristics not mentioned but nevertheless present in similar products of other manufacturers, which can be used as a parameter for the conformity of the goods.

- Instead, it is necessary to include a clause in the contract expressly excluding this type of guarantee.

In other words, in contracts, one must pay attention not only to what is written but also to what is not written.

This case once again demonstrates the importance of drafting a proper and complete contract not only from a commercial, technical, and financial point of view but also from a legal point of view, using the expertise of a lawyer experienced in international commercial contracts.

Finally, it is important not to overlook applicable law and jurisdiction clauses. These aspects are unfortunately often overlooked, even in high-value negotiations, considering these clauses unimportant or even blocking for negotiation, only to regret them when litigation arises or even threatened. See an in-depth discussion here.

写信给 Roberto

Made in Italy: protection of trademarks of special national interest and value

29 1 月 2025

-

意大利

- 知识产权

- 商标和专利

Duties are not paid by foreign governments (as Donald Trump repeatedly said on the electoral campaign) but by the importing companies of the country that issued the tax on the value of the imported product, i.e., in the case of the Trump administration’s recent round of tariffs, U.S. companies. Similarly, Canadian, Mexican, Chinese, and – probably – European companies will pay the import duties on U.S.-origin products levied by their respective countries as a trade retaliation measure against U.S. tariffs.

In this context, several scenarios open up, all of them problematic

- U.S. companies will pay the import taxes

- foreign companies exporting taxed products to the U.S., will see export volumes fall as a result of the price increase

- foreign companies that import products from the U.S., in turn, will pay tariffs imposed by their countries in retaliation to U.S. duties

- intermediate or end customers in markets affected by the tariffs will pay a higher price for imported products

Does the imposition of the duty constitute force majeure?

A frequent first objection of the party affected by the duty (it may be the buyer-importer or the one who resells the product after paying the duty), in such cases, is to invoke force majeure to evade the performance of the contract, which, as a result of the duty has become too onerous.

The application of the duty, however, does not fall under force majeure since we are not faced with an unforeseeable event, resulting in the objective impossibility of fulfilling the contract. The buyer/importer, in fact, can always fulfill the contract, with only the issue of price increase.

Does the imposition of the duty constitute a cause of hardship?

If a situation of excessive onerousness arises after the conclusion of the contract (hardship), the affected party has the right to demand a revision of the price or to terminate the contract.

Is this the case for tariffs? A case-by-case assessment is needed, leading to a finding of recurrence of hardship if an extraordinary and unforeseeable situation exists (in the case of the U.S. duties, which have been announced for months, it isn’t easy to support this) and the price, as a result of the application of the tariff, is manifestly excessive.

These are exceptional situations, rarely applied, and should be investigated further based on the law applicable to the contract. Generally, price fluctuations in international markets are part of business risk and do not constitute sufficient grounds for renegotiating concluded agreements, which remain binding unless the parties have included a hardship clause (discussed below).

Does the application of the tariff entail a right to renegotiate prices?

Contracts already concluded, such as orders already accepted and supply schedules with agreed prices for a certain period, are binding and must be fulfilled according to the original agreements.

In the absence of specific clauses in the contract, the party affected by the tariff is therefore obliged to comply with the previously agreed price and give fulfillment to the agreement.

The parties are free to renegotiate future contracts, e.g.

- the seller may give a discount to lessen the impact of the duty affecting the buyer-importer, or

- the buyer may agree to a price increase to compensate for a duty that the seller has paid to import a component or semi-finished product into his country, and then export the finished product

but this does not affect the validity of contracts already negotatied, which remain binding.

The situation is particularly delicate for companies in the middle of the supply chain, such as those who import raw materials or components from abroad (potentially subject to tariffs, including double duties in the case of repeated import and export) and resell the semi-finished or finished products, since they are not entitled to pass the cost on to the following link in the supply chain, unless this was expressly provided for in the contract with the customer.

What can be done in case of imposition of future duties affecting foreign suppliers or customers?

It is advisable to expressly provide for the right to renegotiate prices, if necessary by adding an addendum to the original agreement. This can be achieved, for example, by a clause providing that in case future events, including any duties, cause an increase in the overall cost of the product above a certain threshold (e.g., 10 percent), the party affected by the tariffs has the right to initiate a renegotiation of the price and, in the event of a failure to agree, can withdraw from the contract.

An example of a clause might be as follows:

Import Duties Adjustment

“If any new import duties, tariffs, or similar governmental charges are imposed after the conclusion of this Contract, and such measures increase a Party’s costs exceeding X% of the agreed price of the Products, the affected Party shall have the right to request an immediate renegotiation of the price. The Parties shall engage in good faith negotiations to reach a fair adjustment of the contractual price to reflect the increased costs.

If the Parties fail to reach an agreement within [X] days from the affected Party’s request for renegotiation, the latter shall have the right to terminate this Contract with [Y] days‘ written notice to other Party, without liability for damages, except for the fulfillment of obligations already accrued.”

‘’Made in Italy” is synonymous of high productive and aesthetic quality and represents an added value, in the international market, for different kind of products, from foodstuffs to clothing, automotive and furniture. In recent years, in Italy, a number of initiatives have been taken at the regulatory level to ensure its promotion, valorization and protection.

In 2024 came into force law no. 206/2023, referred to as the ‘New Made in Italy Law’, followed on 3 July 2024 by the related implementing Decree, by which the Ministry of Enterprise and Made in Italy (hereinafter the ‘Ministry’) introduced relevant provisions including the ones related to an official mark attesting the Italian origin of goods, the fight against counterfeiting (in particular in criminal law), and the promotion of the use of blockchain technology to protect production chains.

Among the new measures, there are specific rules for the protection of trademarks – with at least 50 years of registration or use in Italy – of particular national interest and value (hereinafter “Trademark/s”). The aim of such provisions is to safeguard the heritage represented by Italian trademarks with a long-standing presence on the market, preventing their extinction and guaranteeing their use by companies linked to the Italian territory.

Measures to guarantee the continuity

In order to protect the Trademarks, two distinct possibilities are envisaged

- Notification by companies

The first consists of the takeover by the Ministry of the ownership of Trademarks of companies that will cease their activities. In this regard, the Decree provides that a company owner or licensee of a trademark registered for at least 50 years, or for which it is possible to prove continuous use for at least 50 years, intending to cease its activity definitively, must notify the Ministry in advance of the plan to cease its activity, indicating, in particular, the economic, financial or technical reasons that impose the cessation. Upon receipt of this notification, the Ministry is entitled to take over ownership of the trademark without charge if the trademark has not been assigned for consideration by the owner or licensee company.

This procedure, in particular, is newly implemented, being applicable as of 2 December 2024.

- Revocation for non-use

The second possibility concerns Trademarks suspected of not being used for at least 5 years. In such case, the Ministry may file before the Italian Patent and Trademark Office an application for revocation for non-use and, if the application is granted, proceed with registering the Trademark in its name.

Trademarks of national interest owned by the Ministry will be announced on its Web site https://www.mimit.gov.it/it/impresa/competitivita-e-nuove-imprese/proprieta-industriale/marchi-di-interesse-storico/elenco-marchi.

As of 27 January 2025, one month after the applicability of the procedures at issue in the list are the following:

- INNOCENTI – Application number 302023000141171

- AUTOBIANCHI – Application number 302023000141189

Free licences for Italian or foreign companies wishing to invest in Italy

The Ministry is authorized to use the Trademarks, licensing them exclusively in favor of companies, including foreign ones, that intend to invest in Italy or transfer production activities located abroad to Italy.

In particular, Italian and foreign companies planning to produce in Italy may apply for a licence to use the above-mentioned Trademarks. The application shall contain specific details regarding the planned investment project, with a focus on the employment impact of the same.

Should the Ministry accept the application, the company will be granted a 10-year free licence, renewable on condition that the company maintains production activities within the national borders.

It is to be noted that, in the event that the company interrupts its activities or relocates its plants outside the Italian territory, the licence contract may be terminated immediately.

What’s next?

The recent regulatory measures are aimed, on the one hand, at keeping alive traditional brands that have been used in Italy for many years and, on the other hand, at allowing Italian and foreign companies to benefit from the incentive of free licences, if they decide to produce in Italy.

It will be interesting to monitor the business developments of these provisions in the coming months, in which the list of Trademarks owned by the Ministry will become longer.

“This agreement is not just an economic opportunity. It is a political necessity.” In the current geopolitical context of growing protectionism and significant regional conflicts, Ursula von der Leyen’s statement says a lot.

Even though there is still a long way to go before the agreement is approved internally in each bloc and comes into force, the milestone is highly significant. It took 25 years from the start of negotiations between Mercosur and the European Union to reach a consensus text. The impacts will be considerable. Together, the blocs represent a GDP of over 22 trillion dollars, and are home to over 700 million people.

Our aim here is to highlight, in a simplified manner, the most important information about the agreement’s content and its progress, which we will update here at each stage.

What is it?

The agreement was signed as a trade treaty, with the main goal of reducing import and export tariffs, eliminating bureaucratic barriers, and facilitating trade between Mercosur countries and European Union members. Additionally, the pact includes commitments in areas such as sustainability, labor rights, technological cooperation, and environmental protection.

Mercosur (Southern Common Market) is an economic bloc created in 1991 by Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Now, Bolivia and Chile participate as associated members, accessing some trade agreements, but not fully integrated into the common market. On the other hand, the European Union, with its 27 members (20 of which have adopted the common currency), is a broader union with greater economic and social integration compared to Mercosur.

What does the EU Mercosur agreement include?

Trade in goods:

- Reduction or elimination of tariffs on products traded between the blocs, such as meat, grains, fruits, automobiles, wines, and dairy products (the expected reduction will affect over 90% of the traded goods between the blocks).

- Easier access to European high-tech and industrialized products.

Trade in services:

- Expands access to financial services, telecommunications, transportation, and consulting for businesses in both blocs.

Movement of people:

- Provides facilities for temporary visas for qualified workers, such as technology professionals and engineers, promoting talent exchange.

- Encourages educational and cultural cooperation programs.

Sustainability and environment:

- Includes commitments to combat deforestation and meet the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change.

- Provides penalties for violations of environmental standards.

Intellectual property and regulations:

- Protects geographical indications for European cheese, wines, and South American coffee and cachaça.

- Harmonizes regulatory standards to reduce bureaucracy and avoid technical barriers.

Labor rights:

- Commitment to decent working conditions and compliance with International Labor Organization (ILO) standards.

Which benefits to expect?

- Access to new markets: Mercosur companies will have easier access to the European market, which has more than 450 million consumers, while European products will become more competitive in South America.

- Costs reduction: The elimination or reduction of tariffs could lower the prices of products such as wines, cheese, and automobiles and boost South American exports of meat, grains, and fruits.